Seeing, Sensing, Saying: Holding Patterns in the Homesman (2014)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

108 Kansas History “Facing This Vast Hardness”: the Plains Landscape and the People Shaped by It in Recent Kansas/Plains Film

Premiere of Dark Command, Lawrence, 1940. Courtesy of the Douglas County Historical Society, Watkins Museum of History, Lawrence, Kansas. Kansas History: A Journal of the Central Plains 38 (Summer 2015): 108–135 108 Kansas History “Facing This Vast Hardness”: The Plains Landscape and the People Shaped by It in Recent Kansas/Plains Film edited and introduced by Thomas Prasch ut the great fact was the land itself which seemed to overwhelm the little beginnings of human society that struggled in its sombre wastes. It was from facing this vast hardness that the boy’s mouth had become so “ bitter; because he felt that men were too weak to make any mark here, that the land wanted to be let alone, to preserve its own fierce strength, its peculiar, savage kind of beauty, its uninterrupted mournfulness” (Willa Cather, O Pioneers! [1913], p. 15): so the young boy Emil, looking out at twilight from the wagon that bears him backB to his homestead, sees the prairie landscape with which his family, like all the pioneers scattered in its vastness, must grapple. And in that contest between humanity and land, the land often triumphed, driving would-be settlers off, or into madness. Indeed, madness haunts the pages of Cather’s tale, from the quirks of “Crazy Ivar” to the insanity that leads Frank Shabata down the road to murder and prison. “Prairie madness”: the idea haunts the literature and memoirs of the early Great Plains settlers, returns with a vengeance during the Dust Bowl 1930s, and surfaces with striking regularity even in recent writing of and about the plains. -

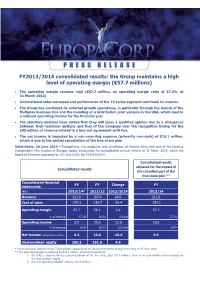

FY2013/2014 Consolidated Results: the Group Maintains a High Level of Operating Margin (€57.7 Millions)

FY2013/2014 consolidated results: the Group maintains a high level of operating margin (€57.7 millions) The operating margin remains high (€57.7 million, an operating margin ratio of 27.3% at 31 March 2014) International sales increased and performance of the TV series segment continued to improve The Group has continued its external growth operations, in particular through the launch of the Multiplex business line and the founding of a distribution joint venture in the USA, which lead to a reduced operating income for the financial year The statutory auditors have stated that they will issue a qualified opinion due to a divergence between their technical analysis and that of the Company over the recognition timing for the $45 million of revenue related to a buy-out agreement with Fox. The net income is impacted by a non-recurring expense (primarily non-cash) of €10.1 million, which is due to the partial cancellation of the free share plan Saint-Denis, 26 June 2014 – EuropaCorp, the producer and distributor of feature films and one of the leading independent film studios in Europe, today announces its consolidated annual results at 31 March 2014, which the Board of Directors approved on 25 June 2014, for FY2013/2014. Consolidated results adjusted for the impact of Consolidated results the cancelled part of the free share plan ** Consolidated financial FY FY Change FY statements (€m) 2013/14* 2012/13 2013/2014 2013/14 Revenue 211.8 185.8 26.0 211,8 Cost of sales -154.1 -129.7 -24.4 -154.1 Operating margin 57.7 56.1 1.6 57.7 % of revenue -

The National Film Preserve Ltd. Presents the This Festival Is Dedicated To

THE NATIONAL FILM PRESERVE LTD. PRESENTS THE THIS FESTIVAL IS DEDICATED TO Stanley Kauffmann 1916–2013 Peter O’Toole 1932–2013 THE NATIONAL FILM PRESERVE LTD. PRESENTS THE Julie Huntsinger | Directors Tom Luddy Kim Morgan | Guest Directors Guy Maddin Gary Meyer | Senior Curator Mara Fortes | Curator Kirsten Laursen | Chief of Staff Brandt Garber | Production Manager Karen Schwartzman | SVP, Partnerships Erika Moss Gordon | VP, Filmanthropy & Education Melissa DeMicco | Development Manager Joanna Lyons | Events Manager Bärbel Hacke | Hosts Manager Shannon Mitchell | VP, Publicity Justin Bradshaw | Media Manager Jannette Angelle Bivona | Executive Assistant Marc McDonald | Theater Operations Manager Lucy Lerner | SHOWCorps Manager Erica Gioga | Housing/Travel Manager Beth Calderello | Operations Manager Chapin Cutler | Technical Director Ross Krantz | Technical Wizard Barbara Grassia | Projection and Inspection Annette Insdorf | Moderator Mark Danner | Resident Curators Pierre Rissient Peter Sellars Paolo Cherchi Usai Publications Editor Jason Silverman (JS) Chief Writer Larry Gross (LG) Prized Program Contributors Sheerly Avni (SA), Paolo Cherchi Usai (PCU), Jesse Dubus (JD), Geoff Dyer (GD), Gian Luca Farinelli (GLF), Mara Fortes (MF), Scott Foundas (SF), Guy Maddin (GM), Leonard Maltin (LM), Jonathan Marlow (JM), Todd McCarthy (TM), Gary Meyer (GaM), Kim Morgan (KM), Errol Morris (EM), David Thomson (DT), Peter von Bagh (PvB) Tribute Curator Short Films Curators Student Prints Curator Chris Robinson Jonathan Marlow Gregory Nava and Bill Pence 1 Guest Directors Sponsored by Audible.com The National Film Preserve, Ltd. Each year, Telluride’s Guest Director serves as a key collaborator in the A Colorado 501(c)(3) nonprofit, tax-exempt educational corporation Festival’s programming decisions, bringing new ideas and overlooked films. -

International & Festivals

COMPANY CV – INTERNATIONAL & FESTIVALS INTERNATIONAL CAMPAIGNS / JUNKETS / TOURS (selected) Below we list the key elements of the international campaigns we have handled, but our work often also involves working closely with the local distributors and the film-makers and their representatives to ensure that all publicity opportunities are maximised. We have set up face-to-face and telephone interviews for actors and film-makers, working around their schedules to ensure that the key territories in particular are given as much access as possible, highlighting syndication opportunities, supplying information on special photography, incorporating international press into UK schedules that we are running, and looking at creative ways of scheduling press. THE AFTERMATH / James Kent / Fox Searchlight • International campaign support COLETTE / Wash Westmoreland / HanWay Films • International campaign BEAUTIFUL BOY / Felix van Groeningen / FilmNation • International campaign THE FAVOURITE / Yorgos Lanthimos / Fox Searchlight • International campaign support SUSPIRIA / Luca Guadagnino / Amazon Studios • International campaign LIFE ITSELF / Dan Fogelman / FilmNation • International campaign DISOBEDIENCE / Sebastián Lelio / FilmNation • International campaign THE CHILDREN ACT / Richard Eyre / FilmNation • International campaign DON’T WORRY, HE WON’T GET FAR ON FOOT / Gus Van Sant / Amazon Studios & FilmNation • International campaign ISLE OF DOGS / Wes Anderson / Fox Searchlight • International campaign THREE BILLBOARDS OUTSIDE EBBING, MISSOURI / -

Id Title Year Format Cert 20802 Tenet 2020 DVD 12 20796 Bit 2019 DVD

Id Title Year Format Cert 20802 Tenet 2020 DVD 12 20796 Bit 2019 DVD 15 20795 Those Who Wish Me Dead 2021 DVD 15 20794 The Father 2020 DVD 12 20793 A Quiet Place Part 2 2020 DVD 15 20792 Cruella 2021 DVD 12 20791 Luca 2021 DVD U 20790 Five Feet Apart 2019 DVD 12 20789 Sound of Metal 2019 BR 15 20788 Promising Young Woman 2020 DVD 15 20787 The Mountain Between Us 2017 DVD 12 20786 The Bleeder 2016 DVD 15 20785 The United States Vs Billie Holiday 2021 DVD 15 20784 Nomadland 2020 DVD 12 20783 Minari 2020 DVD 12 20782 Judas and the Black Messiah 2021 DVD 15 20781 Ammonite 2020 DVD 15 20780 Godzilla Vs Kong 2021 DVD 12 20779 Imperium 2016 DVD 15 20778 To Olivia 2021 DVD 12 20777 Zack Snyder's Justice League 2021 DVD 15 20776 Raya and the Last Dragon 2021 DVD PG 20775 Barb and Star Go to Vista Del Mar 2021 DVD 15 20774 Chaos Walking 2021 DVD 12 20773 Treacle Jr 2010 DVD 15 20772 The Swordsman 2020 DVD 15 20771 The New Mutants 2020 DVD 15 20770 Come Away 2020 DVD PG 20769 Willy's Wonderland 2021 DVD 15 20768 Stray 2020 DVD 18 20767 County Lines 2019 BR 15 20767 County Lines 2019 DVD 15 20766 Wonder Woman 1984 2020 DVD 12 20765 Blackwood 2014 DVD 15 20764 Synchronic 2019 DVD 15 20763 Soul 2020 DVD PG 20762 Pixie 2020 DVD 15 20761 Zeroville 2019 DVD 15 20760 Bill and Ted Face the Music 2020 DVD PG 20759 Possessor 2020 DVD 18 20758 The Wolf of Snow Hollow 2020 DVD 15 20757 Relic 2020 DVD 15 20756 Collective 2019 DVD 15 20755 Saint Maud 2019 DVD 15 20754 Hitman Redemption 2018 DVD 15 20753 The Aftermath 2019 DVD 15 20752 Rolling Thunder Revue 2019 -

Article Thématique

ARTICLE HORS THÈME Les représentations filmiques de la santé mentale des migrants : pistes réflexives Mouloud Boukala 1 Résumé Cet article propose des pistes réflexives sur l’analyse des représentations cinématographiques, principalement fictionnelles, abordant la santé mentale des migrants. L’un des enjeux de notre réflexion est de cerner les films se consacrant à ce sujet et, de les identifier puis d’analyser comment des individus – en l’occurrence des migrants malades – y sont représentés. Qu’apporte ce mode de figuration qu’est le cinéma à la compréhension de la santé mentale en contexte migratoire ? Le cinéma fictionnel est-il source de stéréotypie (les migrants comme porteurs de danger social, responsables des déficits publics, etc.) ou marque-t-il une rupture avec des représentations réductrices ? Le cinéma met-il en image et en sons les impacts des violences, de l’isolement affectif, de la guerre, des persécutions, des menaces, des troubles du sommeil sur la santé mentale des migrants? La fiction rend-elle compte des espaces cliniques et thérapeutiques proposés aux migrants? Rattachement de l’auteur 1 Université du Québec à Montréal, Montréal Correspondance [email protected] Mots clés migrations; santé mentale; cinéma; fictions; esclavage; guerre. Pour citer cet article Boukala, M. (2014). Les représentations filmiques de la santé mentale des migrants : pistes réflexives. Alterstice, 4(2), 85-98. Alterstice – Revue Internationale de la Recherche Interculturelle, vol. 4, n°2 86 Mouloud Boukala Cet article propose des pistes réflexives sur l’analyse des représentations cinématographiques, principalement fictionnelles1, abordant la santé mentale des migrants2. L’un des enjeux de notre réflexion est de cerner les films se consacrant à ce sujet et de les identifier puis d’analyser comment des individus – en l’occurrence des migrants malades – y sont représentés. -

Bath Film Festival Awards

BATH FILM F esTIvAL Bath Film Festival 13 – 23 November, 2014 bathfilmfestival.org.uk 27 November – 14 December 2014 The UK’s favourite Christmas Market Over 170 stalls in the most magical of settings Local, handmade and unique gifts More than 60 new traders this year BathChristmasMarket.co.uk QUALITY ASSURED VISITOR AT TRACTION Hello & Welcome Bath Film Festival 2014 is here, the best time of the year for film. The line up is fantastic; we have 19 previews, 20 special guests, family films, sci-fi, special events, feature docs and a new venue. Ten days to gorge yourself on the best films on offer: enjoy! Philip Raby, Director Contents Films at-a-glance 4 – 5 Some of the faces behind the scenes 7 F Rated Films 9 Bath Spa University Strand 11 FilmScore 12 Burfield Sci-Fi / Family 13 Documentaries and Q&As 15 Bath Film Festival Awards 17 Our Sponsors 18 – 19 Map and Bookings 20 – 21 All the films 22 - 41 Registered Office: 2nd Floor, Abbey Chambers, Kingston Parade, Bath BA1 1LY Tel: 01225 463 458 Facebook: Facebook.com/BathFilmFestival Twitter: @bathfilm #BFF2014 Registered in the UK no. 3400371 Registered Charity no. 1080952 bathfilmfestival.org.uk facebook.com/BathFilmFestival @BathFilm 3 This year’s film programme Film listings at-a-glance go to page 22 EvENt vENuE Start PagE EvENt vENuE Start PagE Thursday 13 November Sunday 16 November What We Do In The Shadows Little@Komedia 19:00/21:00 22 My Old Lady Little Theatre 16:00 25 Invasion Of The Body Snatchers ODEON 21:00 22 Difret Chapel Arts 17:30 26 Northern Soul The Rondo 18:40 26 -

June 2021 San Antonio, TX 78278-2261 Officers Howdy Texican Rangers

The Texas Star Newsletter for the Texican Rangers A Publication of the Texican Rangers An Authentic Cowboy Action Shooting Club That Treasures & Respects the Cowboy Tradition SASS Affiliated PO Box 782261 June 2021 San Antonio, TX 78278-2261 Officers Howdy Texican Rangers President Asup Sleeve (954) 632-3621 [email protected] Vice President Its official, summer is here! The June Burly Bill Brocius matches were a huge success thanks to the 210-310-9090 work of the loyal Texicans who came out [email protected] to maintain our club range. The June matches continued and Secretary improved on the fast pace stages set in Tombstone Mary May. With 50 competitors on Saturday, 210-262-7464 Alamo Andy bested the field with a stage [email protected] average of 18.4 seconds while taking the honor of Top Overall Cowboy. Panhandle Treasurer Cowgirl came in second place overall and A.D. Top Lady Shooter for the day. 210-862-7464 Sunday saw the Top Overall shooter [email protected] position go to Brazos Bo with an average stage time under 20 seconds. Talk about Range Master consistency, Panhandle Cowgirl reigned in the Top Lady honors on Sunday as well, Colorado Horseshoe for a back-to-back sweep of the Lady 719-231-6109 category. [email protected] Other notable awards were the 15 shooters who completed all five stages Communications perfectly clean on Saturday and one on Dutch Van Horn Sunday. Yee haw to all the shooters with 210-823-6058 a fast paced and fun two days of shooting. -

29Th JUNE > 1St [email protected]

MINUTES Kandimari 61 rue Danton 92300 Levallois-Perret France T : +33 9 52 10 56 08 2016 > MINUTES JULY 29th JUNE > 1st [email protected] www.kandimari.com Contact : Marie Barraco, director – [email protected] www.serieseries.fr 29TH JUNE - 1ST JULY 2 EDITORIAL 3 THEY STEER SÉRIE SERIES 4 SCRIPTED SERIES: A REFLECTION OF OUR SOCIETY ? 8 THE SERIES 10 Flowers (United Kingdom) 13 Valkyrien (Norway) 16 The Bonus Family (Sweden) 18 The Day Will Come (Denmark) 20 Downshifters (Finland) 22 Kosmo (Czech Republic) 24 Tomorrow I Quit (Germany) 26 The Secret (United Kingdom) 29 Marcella (United Kingdom) 30 Skam (Norway) & #hashtag (Sweden) 33 Shield 5 (United Kingdom) 36 Studio+: Amnêsia & TANK (France) 38 Tytgat Chocolat (Belgium) 40 The Collection (United Kingdom / France) 42 Monster (Norway) 44 Rocco Schiavone (Italy) 46 Guyane / Ouro (France) 49 Farang (Sweden) 50 Unité 42 (Belgium) 51 Foreign Bodies (United Kingdom) 52 Before We Die (Sweden) 53 Eden (Germany) 54 Generation B (Belgium) 58 DISCUSSIONS 56 Mayday (Denmark) 60 Masterclass : Lars Blomgren 57 Children’s sessions 63 Masterclass : Anaïs Schaaff 66 Masterclass : Matthew Graham 69 Masterclass : Jeppe Gjervig Gram 72 Masterclass : Nathaniel Méchaly 74 Contrasting Perspectives: Roar Skau Olsen & Niklas Schak 76 Debate: Cultural identities and the international market 80 One Vision: Issaka Sawadogo 81 One Vision: Anne Landois & Caroline Proust 82 One Vision: Tone C. Rønning 83 Let’s talk about commissioning! 86 Broadcasters’ Conclaves 87 Spotlight on trailers by Série Series 88 EVENING -

Les Représentations Filmiques De La Santé Mentale Des Migrants : Pistes Réflexives Mouloud Boukala

Document generated on 09/28/2021 9:21 p.m. Alterstice Revue internationale de la recherche interculturelle International Journal of Intercultural Research Revista International de la Investigacion Intercultural Les représentations filmiques de la santé mentale des migrants : pistes réflexives Mouloud Boukala Santé mentale et sociétés plurielles Article abstract Volume 4, Number 2, 2014 Cet article propose des pistes réflexives sur l’analyse des représentations cinématographiques, principalement fictionnelles, abordant la santé mentale URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1077428ar des migrants. L’un des enjeux de notre réflexion est de cerner les films se DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1077428ar consacrant à ce sujet et, de les identifier puis d’analyser comment des individus – en l’occurrence des migrants malades – y sont représentés. See table of contents Qu’apporte ce mode de figuration qu’est le cinéma à la compréhension de la santé mentale en contexte migratoire ? Le cinéma fictionnel est-il source de stéréotypie (les migrants comme porteurs de danger social, responsables des déficits publics, etc.) ou marque-t-il une rupture avec des représentations Publisher(s) réductrices ? Le cinéma met-il en image et en sons les impacts des violences, de Alterstice l’isolement affectif, de la guerre, des persécutions, des menaces, des troubles du sommeil sur la santé mentale des migrants ? La fiction rend-elle compte des espaces cliniques et thérapeutiques proposés aux migrants ? ISSN 1923-919X (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Boukala, M. (2014). Les représentations filmiques de la santé mentale des migrants : pistes réflexives. Alterstice, 4(2), 85–98. https://doi.org/10.7202/1077428ar © Mouloud Boukala, 2014 This document is protected by copyright law. -

THE HOMESMAN Fiche Film

THE HOMESMAN de Tommy Lee Jones Compétition officielle Sortie le 21 mai Synopsis En 1854, trois femmes ayant perdu la raison sont confiées à Mary Bee Cuddy, une pionnière forte et indépendante originaire du Nebraska. Sur sa route vers l’Iowa, où ces femmes pourront trouver refuge, elle croise le chemin de Georges Briggs, un rustre vagabond qu’elle sauve d’une mort imminente. Ils décident de s'associer afin de faire face, ensemble, à la rudesse et aux dangers qui sévissent dans les vastes étendues de la Frontière. Presse française MOONFLEET – Cédric Landemaine & Mounia Wissinger 10 rue d'Aumale - 75009 Paris – Tél. : 01 53 20 01 20 [email protected] ; [email protected] Liste artistique George Briggs Tommy LEE JONES Mary Bee Cuddy Hilary SWANK Tabitha Hutchinson Hailee STEINFELD Altha Carter Meryl STREEP Aloysius Duffy James SPADER Reverend Alfred Dowd John LITHGOW Freighter Tim BLAKE NELSON Garn Sours Jesse PIEMONS Vester Belknap William FICHTNER Arabella Sours Grace GUMMER Theoline Belknap Miranda OTTO Gro Svendsen Sonja RICHTER Thor Svendsen David DENCIK Liste technique Réalisation Tommy Lee Jones Scénario Kieran Fitzgerald, Tommy Lee Jones, Wesley Oliver Inspiré de “THE HOMESMAN” par Glendon Swarthout Producteurs Brian Kennedy, Tommy Lee Jones, Michael Fitzgerald, Luc Besson, Peter Brant Directeur de photographie Rodrigo Prieto Musique Marco Beltrami Distribution EuropaCorp Distribution 20, rue Ampère – 93 413 Saint Denis Cédex Tél. : 01 55 99 51 21 Le matériel presse : LES PHOTOS http://download.europacorp.com/extranet/THE-HOMESMAN_Photos.zip L’AFFICHE http://download.europacorp.com/extranet/HOMESMAN_Affiche.zip Presse française MOONFLEET – Cédric Landemaine & Mounia Wissinger 10 rue d'Aumale - 75009 Paris – Tél. -

Da Lunedì 18, Finalmente Si Riaprono Le Porte Per Le Messe Partecipate

Pasian di Prato a pag.17 Cividale a pag. 22 La zona artigianale Riaprono i luoghi si allarga di un terzo della cultura Settimanale locale ROC Poste Italiane S.p.a. mercoledì 13 maggio 2020 Spedizione in abb. post. Decreto Legge 353/2003 anno XCVII n. 20 | euro 1.50 (conv. in L. 22/2/2004 n. 46) Art. 1, comma 1, DCB Udine www. lavitacattolica.it SETTIMANALE DEL FRIULI sofferenza spirituale e che speriamo e fisica, fecero i 49 martiri di Abitinia trova spiegazione nella famosa definizione Lettera dell’Arcivescovo vogliamo non accada più. Non vi nascondo al tempo della persecuzione scatenata da della Costituzione dogmatica “Lumen Senza l’Eucarestia la speranza che questo digiuno sia stato Diocleziano: “Sine Dominico non possumus!”. gentium” del Concilio Vaticano II: uno stimolo a riscoprire l’importanza vitale Contro il divieto imposto dall’editto “Partecipando al sacrificio eucaristico, fonte non possiamo vivere che ha, per un battezzato, la celebrazione dell’imperatore, essi avevano continuato e apice di tutta la vita cristiana, [i fedeli] dell’Eucaristia. Essa è certamente una a partecipare all’Eucaristia celebrata offrono a Dio la vittima divina e se stessi” Cari Fratelli e Sorelle, di quelle dimensioni essenziali della vita dal presbitero Saturnino. Al proconsole (n. 11). Il Catechismo della Chiesa lunedì 18 maggio ai fedeli verrà di un cristiano che sto richiamando nelle Anulino che chiedeva ragione di quella Cattolica riconferma: “L’Eucaristia è fonte nuovamente offerta la possibilità di lettere che, attraverso “La Vita Cattolica”, disobbedienza essi risposero: “Noi non e culmine di tutta la vita cristiana” (n.