Navies, Coast Guards, the Maritime Community and International Stability

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"Online" Application the Candidates Need to Logon to the Website and Click Opportunity Button and Proceed As Given Below

1 JOIN INDIAN COAST GUARD (MINISTRY OF DEFENCE) AS NAVIK (GENERAL DUTY) 10+2 ENTRY - 02/2020 BATCH APPLICATION WILL BE ACCEPTED ‘ONLINE’ FROM 26 JAN TO 02 FEB 2020 1. Applications are invited from male Indian nationals possessing educational qualifications and age as prescribed below, for recruitment to the post of Navik (General Duty) in the Indian Coast Guard, an Armed Force of the Union. 2. Educational Qualification. 10+2 passed with Maths and Physics from an education board recognised by Central/State Government with minimum 50% aggregate marks. (5 % relaxation in minimum cut off will be given for SC/ST candidates and outstanding sports personnel of National level who have obtained Ist , IInd or IIIrd position in any field sports events at the Open National Championship/ Inter-state National Championship. 3. Age. Minimum 18 Years and maximum 22 years i.e. born between 01 Aug 1998 to 31 Jul 2002 (both dates inclusive). Upper age relaxation of 5 years for SC/ST and 3 years for OBC candidates. 4. Pay, Perks and Others Benefits. On joining Indian Coast Guard, you will be placed in Basic pay of Rs. 21700/- (Pay Level-3) plus Dearness Allowance and other allowances based on nature of duty/place of posting as per the prevailing regulations. 5. Vacancy. The total post for Navik (GD) 02/2020 batch is 260 (approximately). UR(GEN) EWS OBC ST SC Total 113 26 75 13 33 260 Note: - These vacancies are tentative and may change depending on availability of training slots. 6. Promotion and Perquisites. (a) Promotion prospects exist upto the rank of Pradhan Adhikari with pay scale Rs. -

13. the Maritime Safety Agency (MSA) / Japan Coast Guard (JCG)

13. The Maritime Safety Agency (MSA) / Japan Coast Guard (JCG) The Maritime Safety Agency (MSA), which was officially renamed the Japan Coast Guard (JCG) in April 2000, is effectively a fourth branch of the Japanese military. Originally established as the Maritime Safety Board in April 1948, it has been reorganised many times since then, and its roles and missions have expanded to include not only guarding Japan’s enormous coastline and providing search and rescue services, but also constabulary operations in the sea lanes and high seas.1 In May 1998, two MSA vessels were sent to Singapore ready to evacuate Japanese residents from Indonesia, where the political situation was ‘unstable’ and ‘unpredictable’.2 Since 1996, the MSA/JCG has been increasingly involved in protecting the Senkaku Islands and policing other disputed areas in the East China Sea.3 JCG patrol boats sank a suspected North Korean ‘spy ship’ near Amami–Oshima Island in December 2001.4 It is the primary Japanese agency in the US-led Proliferation Security Initiative (PSI), which involves the interdiction of ships on the high seas suspected of carrying weapons of mass destruction or related materials.5 In September 2003 the JSG represented Japan in the PSI exercise in the Coral Sea off the north-east coast of Australia.6 In January 2008, armed JCG officers accompanied Japanese whaling ships being confronted by protest boats in the Southern Ocean near Antarctica.7 Although part of the Ministry of Transportation, in reality the MSA functions as a quasi-autonomous and capable maritime defence force, with its own ships and aircraft. -

Summary Report

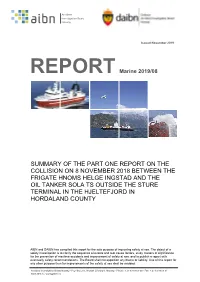

Issued November 2019 REPORT Marine 2019/08 SUMMARY OF THE PART ONE REPORT ON THE COLLISION ON 8 NOVEMBER 2018 BETWEEN THE FRIGATE HNOMS HELGE INGSTAD AND THE OIL TANKER SOLA TS OUTSIDE THE STURE TERMINAL IN THE HJELTEFJORD IN HORDALAND COUNTY AIBN and DAIBN has compiled this report for the sole purpose of improving safety at sea. The object of a safety investigation is to clarify the sequence of events and root cause factors, study matters of significance for the prevention of maritime accidents and improvement of safety at sea, and to publish a report with eventually safety recommendations. The Board shall not apportion any blame or liability. Use of this report for any other purpose than for improvements of the safety at sea shall be avoided. Accident Investigation Board Norway • P.O. Box 213, N-2001 Lillestrøm, Norway • Phone: + 47 63 89 63 00 • Fax: + 47 63 89 63 01 www.aibn.no • [email protected] This is a summary of the AIBN’s part one report following the accident. The AIBN refers to the full text in the part one report for an accurate description and details of the sequence of events, factual information and the analysis of the accident up until the time when the collision occurred. Only the official part one report describes the AIBN’s investigation and the findings completely. The report is available on www.aibn.no. This report has been translated into English and published by the Accident Investigation Board Norway (AIBN) to facilitate access by international readers. As accurate as the translation might be, the original Norwegian text takes precedence as the report of reference. -

South Korea Section 3

DEFENSE WHITE PAPER Message from the Minister of National Defense The year 2010 marked the 60th anniversary of the outbreak of the Korean War. Since the end of the war, the Republic of Korea has made such great strides and its economy now ranks among the 10-plus largest economies in the world. Out of the ashes of the war, it has risen from an aid recipient to a donor nation. Korea’s economic miracle rests on the strength and commitment of the ROK military. However, the threat of war and persistent security concerns remain undiminished on the Korean Peninsula. North Korea is threatening peace with its recent surprise attack against the ROK Ship CheonanDQGLWV¿ULQJRIDUWLOOHU\DW<HRQS\HRQJ Island. The series of illegitimate armed provocations by the North have left a fragile peace on the Korean Peninsula. Transnational and non-military threats coupled with potential conflicts among Northeast Asian countries add another element that further jeopardizes the Korean Peninsula’s security. To handle security threats, the ROK military has instituted its Defense Vision to foster an ‘Advanced Elite Military,’ which will realize the said Vision. As part of the efforts, the ROK military complemented the Defense Reform Basic Plan and has UHYDPSHGLWVZHDSRQSURFXUHPHQWDQGDFTXLVLWLRQV\VWHP,QDGGLWLRQLWKDVUHYDPSHGWKHHGXFDWLRQDOV\VWHPIRURI¿FHUVZKLOH strengthening the current training system by extending the basic training period and by taking other measures. The military has also endeavored to invigorate the defense industry as an exporter so the defense economy may develop as a new growth engine for the entire Korean economy. To reduce any possible inconveniences that Koreans may experience, the military has reformed its defense rules and regulations to ease the standards necessary to designate a Military Installation Protection Zone. -

Rob Huebert Rhueb Ert@ Ucal Gary.Ca

Centre for Military and Strategic Studies THE CONTINUALLY CHANGING ARCTIC SECURITY ENVIRONMENT TThe Society Of Naval Architects And Marine Engineers – Arctic Section Rob Huebert Rhue ber t@ucal gary.ca Calgary April 20 , 2012 Main Themes • Increasing International and Canadian Debate as to what the Arctic will look like in the future – physical; economic; cultural; and geopolitical • A New Arctic Security Environment is Forming on a Global Basis – What will it look like? • How will this impact Canada? United S?WhdCddhUidStates? What does Canada and the United States need to do? The Transforming Arctic • The Arctic is a state of massive transformation – Climate Change – Resource Development – (was up to a high $140+ barrel of oil- now $108 barrel) – Geopolitical Transformation/Globalization The Image of Change: Accessibility The Melting Ice: Movement of Ice Sept 2007-April 2008 Source: Canadian Ice Service The Economics: The Hope of Resources Oil and Gas: Oil Resources and Gas of the North Source: AMAP Uncertain Maritime jurisdiction & boundaries in the Arctic www.dur.ac.uk/ibru/resources/arctic The Changing Technologies: PdAiLNGProposed Arctic LNG Source: Samsung Heavy Industries New Signs of Cooperation • Public Pronouncements • Creation of Arctic Council • Application of UNCLOS • Norway-RiMiiBRussia Maritime Bound ary Delimitation 2010 • Arctic Council – Search and Rescue Agreement 2010 • Public Pronouncements….. New Signs of Competition • Russia – Renewed Assertiveness/ Petrodollars • United States – Multi-lateral reluctance/emerging -

Join Indian Coast Guard (Ministry of Defence) As Navik (General Duty) 10+2 Entry - 02/2018 Batch Application Will Be Accepted ‘Online’ from 24 Dec 17 to 02 Jan 18

1 JOIN INDIAN COAST GUARD (MINISTRY OF DEFENCE) AS NAVIK (GENERAL DUTY) 10+2 ENTRY - 02/2018 BATCH APPLICATION WILL BE ACCEPTED ‘ONLINE’ FROM 24 DEC 17 TO 02 JAN 18 1. Applications are invited from male Indian nationals possessing educational qualifications and age, as prescribed below, for recruitment to the post of Navik (General Duty) in the Indian Coast Guard, an Armed Force of the Union. 2. Educational Qualification. 10+2 passed with 50% marks aggregate in total and minimum 50% aggregate in Maths and Physics from an education board recognized by Central/State Government. (5 % relaxation in above minimum cut off will be given for SC/ST candidates and outstanding sports person of National level who have obtained 1st, 2nd or 3rd position in any field sports events at the Open National Championship/ Interstate National Championship. This relaxation will also be applicable to the wards of Coast Guard uniform personnel deceased while in service). 3. Age. Minimum 18 Years and maximum 22 years i.e. between 01 Aug 1996 to 31 Jul 2000 (both dates inclusive). Upper age relaxation of 5 years for SC/ST and 3 years for OBC candidates. 4. Pay, Perks and Others Benefits:- On joining Indian Coast Guard, you will be placed in Basic pay Rs. 21700/- (Pay Level-3) plus Dearness Allowance and other allowances based on nature of duty/place of posting as per the regulation enforced time to time. 5. Promotion and Perquisites. (a) Promotion prospects exist up to the rank of Pradhan Adhikari with pay scale Rs. 47600/- (Pay Level 8) with Dearness Allowance. -

Annex List of National Operational Contact Points Responsible for the Receipt, Transmission and Processing of Urgent Reports On

18-19.(CD) DIN-Annex 2 to SOPEP 08.28.14-CONTACT UPDATE 10.20.17 (unredacted) ANNEX LIST OF NATIONAL OPERATIONAL CONTACT POINTS RESPONSIBLE FOR THE RECEIPT, TRANSMISSION AND PROCESSING OF URGENT REPORTS ON INCIDENTS INVOLVING HARMFUL SUBSTANCES, INCLUDING OIL FROM SHIPS TO COASTAL STATES 1 The following information is provided to enable compliance with Regulation 37 of MARPOL Annex I which, inter alia, requires that the Shipboard Oil Pollution Emergency Plan (SOPEP) shall contain a list of authorities or persons to be contacted in the event of a pollution incident involving such substances. Requirements for oil pollution emergency plans and relevant oil pollution reporting procedures are contained in Articles 3 and 4 of the 1990 OPRC Convention. 2 This information is also provided to enable compliance with Regulation 17 of MARPOL Annex II which, inter alia, requires that the shipboard marine pollution emergency plans for oil and/or noxious liquid substances shall contain a list of authorities or persons to be contacted in the event of a pollution incident involving such substances. In this context, requirements for emergency plans and reporting for hazardous and noxious substances are also contained in Article 3 of the 2000 OPRC-HNS Protocol. 3 Resolution MEPC.54(32), as amended by resolution MEPC.86(44), on the SOPEP Guidelines and resolution MEPC.85(44), as amended by resolution MEPC.137(53), on the Guidelines for the development of Shipboard Marine Pollution Emergency Plans for Oil and/or Noxious Liquid Substances adopted by the IMO require that these shipboard pollution emergency plans should include, as an appendix, the list of agencies or officials of administrations responsible for receiving and processing reports. -

Planning for a Secure City 403880 789811 9

Planning for a Secure City Undergirding the perceptible dimensions of a liveable city—a bustling economy, dazzling skyline, state-of-the-art public infrastructure and amenities—is its ability to provide its inhabitants and visitors alike the confidence that their personal STUDIES URBAN SYSTEMS safety is ensured and safeguarded. Yet, at times, balancing security and urban design needs presents unique, though not insurmountable, challenges. This Urban Systems Study charts the critical role that security planning and urban design have together played in Singapore’s transformation from being the crime-ridden city that it was some 50 years ago to one of the safest places in the world today. It discusses the country’s use of innovative ideas and technology, its pragmatic approach to security enforcement and urban planning, and its willingness to challenge traditional Planning for A Secure City norms of security provision where necessary. It also examines how neither liveability nor security was compromised in Planning for Singapore’s plans to better prepare itself for emerging security and societal threats. a Secure City This book additionally highlights how the co-opting or active involvement of the public in various security-related initiatives, and the resulting trust built between the government and people, have complemented and enhanced the efforts of Singapore’s security and planning agencies in creating a secure city. “ A good city, first you must feel safe in it. There’s no use having good surroundings but you are afraid all the time… Today a woman can run at three o’clock in the morning… [go] jogging… She will not be raped. -

Smart Border Management: Indian Coastal and Maritime Security

Contents Foreword p2/ Preface p3/ Overview p4/ Current initiatives p12/ Challenges and way forward p25/ International examples p28/Sources p32/ Glossary p36/ FICCI Security Department p38 Smart border management: Indian coastal and maritime security September 2017 www.pwc.in Dr Sanjaya Baru Secretary General Foreword 1 FICCI India’s long coastline presents a variety of security challenges including illegal landing of arms and explosives at isolated spots on the coast, infiltration/ex-filtration of anti-national elements, use of the sea and off shore islands for criminal activities, and smuggling of consumer and intermediate goods through sea routes. Absence of physical barriers on the coast and presence of vital industrial and defence installations near the coast also enhance the vulnerability of the coasts to illegal cross-border activities. In addition, the Indian Ocean Region is of strategic importance to India’s security. A substantial part of India’s external trade and energy supplies pass through this region. The security of India’s island territories, in particular, the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, remains an important priority. Drug trafficking, sea-piracy and other clandestine activities such as gun running are emerging as new challenges to security management in the Indian Ocean region. FICCI believes that industry has the technological capability to implement border management solutions. The government could consider exploring integrated solutions provided by industry for strengthening coastal security of the country. The FICCI-PwC report on ‘Smart border management: Indian coastal and maritime security’ highlights the initiatives being taken by the Central and state governments to strengthen coastal security measures in the country. -

The French White Paper on Defence and National Security (2008) 3

FRENCH DEFENCE 2009 Texts and exercises by Philippe Rostaing : 1. French Defence Organization 2. French Defence Policy : the French White Paper on Defence and National Security (2008) 3. The French Army 4. The French Air Force 5. The French Navy 6. The French Gendarmerie 7. Intelligence and the French Intelligence Community Update : March 2009 1 1. French Defence Organization Read this text carefully. You will then be able to do the following exercises : President of the French Republic Prime Minister Defence Minister Armed Forces Chief of Staff Army Chief Air Force Navy Chief Gendarmerie of Staff Chief of of Staff Director- Staff General 1. The Constitution of October 4th,1958, gives the President of the French Republic the position of Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces (Article 15). In his capacity as guarantor of national independence, territorial integrity and treaty compliance (Article 5), he alone may decide to commit nuclear forces. Within specific councils under his authority (the Council of Ministers, the Defence Council), the President defines national defence policies and makes decisions in defence matters. He is responsible for appointing senior civilian and military officials (Article 13). 2. The French government determines and executes national policies and thus may use armed force (Article 20). The Prime Minister has responsibility for national defence. He implements the decisions made by the President and is supported by the General Secretariat for National Defence (SGDN) in charge of interdepartmental defence coordination. 3. The Defence Minister has authority over the Ministry of Defence and executes military defence policies. He reports directly to the Prime Minister. -

Safe, Sustainable Shipping Table of Contents

Safe, Sustainable Shipping Table of Contents Our Coverage Area 1 Quote from the Board Chair 1a President’s Message 3 2019 Highlights 5 Best in Class 7 Safe, Sustainable Shipping 9 2019 Year in Review 11 Prevent 13 Respond 14 Pioneer 15 Financial Stewardship & Accountability 17 Board Roster Back Cover • 2019 Annual Report Safe, Sustainable Shipping Our Coverage Area The Network’s area of service is incredibly vast. Flip the half page to hear why our board chair is proud of the work we consistently do. Beaufort Chukchi Sea Sea Western Alaska Captain of the Port Zone Prince William Sound Captain of the Port Zone Risk Reduction Areas Nontank Authorized Passes Response Hubs Gulf of Bering Sea Alaska Bristol Bay Buldir Pass Unimak Pass Amchitka Pass Amukta Pass Pacific Ocean 1 • 2019 Annual Report Safe, Sustainable Shipping Our Coverage Area The Network’s area of service is incredibly vast. Flip the half page to hear why our board chair is proud of the work we consistently do. Beaufort Chukchi Sea Sea Western Alaska Captain of the Port Zone Prince William Sound Captain of the Port Zone From the Risk Reduction Areas Nontank Authorized Board Chairman Passes Response Hubs “ Maritime shipping is a cornerstone of our global economy. As our industry continues to break new ground – whether it be cleaner fuel, advances in the prevention of maritime incidents, or exploring new routes through the Arctic – the Network is committed to fostering an environment of safe, sustainable shipping in balance with cost.” Gulf of Bering Sea - Network Board Chair MichaelAlaska Moore VP, Pacific Merchant Shipping Association Bristol Bay Buldir Pass Unimak Pass Amchitka Pass Amukta Pass Pacific Ocean 1 Message from the President & CEO H R O U G H P H T A R G T T N N E 2019 was a year of growth and change – and we fully anticipate 2020 will be one Our strength and core competency is E R as well. -

Submission-Mare-Liberum

1 Submission to the Special Rapporteur on the human rights of migrants: pushback practices and their impact on the human rights of migrants by Mare Liberum Mare Liberum is a Berlin based non-profit-association, that monitors the human rights situation in the Aegean Sea with its own ships - mainly of the coast of the Greek island of Lesvos. As independent observers, we conduct research to document and publish our findings about the current situation at the European border. Since March 2020, Mare Liberum has witnessed a dramatic increase in human rights violations in the Aegean, both at sea and on land. Collective expulsions, commonly known as ‘pushbacks’, which are defined under ECHR Protocol N. 4 (Article 4), have been the most common violation we have witnessed in 2020. From March 2020 until the end of December 2020 alone, we counted 321 pushbacks in the Aegean Sea, in which 9,798 people were pushed back. Pushbacks by the Hellenic Coast Guard and other European actors, as well as pullbacks by the Turkish Coast Guard are not a new phenomenon in the Aegean Sea. However, the numbers were significantly lower and it was standard procedure for the Hellenic Coast Guard to rescue boats in distress and bring them to land where they would register as asylum seekers. End of February 2020 the political situation changed dramatically when Erdogan decided to open the borders and to terminate the EU-Turkey deal of 2016 as a political move to create pressure on the EU. Instead of preventing refugees from crossing the Aegean – as it was agreed upon in the widely criticised EU-Turkey deal - reports suggested that people on the move were forced towards the land and sea borders by Turkish authorities to provoke a large number of crossings.