Metro-Cammell Diesel-Electric Pullman Trains by R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

About Queenspark Books

About QueenSpark Books QueenSpark Books was founded in 1972 as part of a campaign to save the historic Royal Spa in Brighton's Queen's Park from being converted to a casino. The campaign was successful and it inspired participants to start collecting memories of people living in Brighton and Hove to preserve for future generations. QueenSpark Books is now the longest-running organisation of its kind in the UK. th More than one hundred books later, as part of our 45 anniversary celebrations, we are making the original texts of many of our out-of-print books available for the first time in many years. We thank you for choosing this book, and if you can make a donation to QueenSpark Books, please click on the “donate” button on the book page on our website. This book remains the copyright of QueenSpark Books, so if reproducing any part of it, please ensure you credit QueenSpark Books as publisher. Foreword – Pullman Attendant by Bert Hollick, 1991 In 1935, fifteen year old Bert Hollick signed on at Brighton Station for his first shift on a Pullman Train. Working on the midnight shift from Victoria to Brighton including the famous Brighton Belle, he learned to ladle soup from a tureen at seventy-five miles per hour and serve a three-course lunch in a speedy fifty-eight minutes. Bert’s life story is told in a style that conveys wonderfully the atmosphere of the Pullman Cars, as well as providing interesting factual details of railway life. Bert worked at a time when a twelve to fourteen hour day was commonplace, and wages were a meagre £2 a week, despite providing a luxury service to everyday travellers. -

Pullman Car Services-Archive

PULLMAN CAR SERVICES-ARCHIVE The Quality of Service is Remembered Long after the Price is Forgotten SOUTHERN RAILWAY GANGWAYED BOGIE LUGGAGE VAN S2464. T.Bye - Pullman Car Services-Archive. Pullman Car Services-Archive - Issue 4 - Page 1 of 50 Cover Photograph - G.Plumb. Battle of Britain Pacific No.34051 ‘Winston Churchill’ hauling the funeral train passing Feltham. 1. 1905 to 1961. Starting its working life on the London & South Western Railway as Third Class Brake coach in October 1905, and formed part of a four coach set. Between 1927 and 1928 many of the four coach sets were converted into three coach ‘DC’ electric units and two coach trailer sets. The coach bodies were mounted on new longer 62 foot underframes, the original L&SWR underframes of 49 foot and 51 foot were not scrapped. In April 1928 authorisation was given to Ashford works to undertake the construction of fifty ‘GANGWAYED BOGIE LUGGAGE VAN’s’ (GBL). Construction commenced in March 1930 through to October 1930. The GBL’s were allocated the numbers 2281 to 2330. Authorisation was given in April 1929 for Ashford works to construct a further forty GBL’s. Construction commenced in November 1930 through to May 1931 with the allocation of numbers No.2331 to 2370. This was followed by a further thirty GBL’s being authorised for Ashford works to construct in April 1930, with construction commencing in July 1931 through to September 1931. The first twenty one (No.2461 to 2481) to diagram number 3099 were fifty three feet three inches long and the remaining nine (No.2482 to 2490) to diagram number 3098 were fifty one feet three inches long. -

Barrowmore Model Railway Journal

ISSN 1745-9842 Barrowmore Model Railway Journal Number30 March2012 Published on behalf of.Barrowmore Model Railway Group by the Honormy Editor: David Goodwin, "Cromer", Chun:1l Road, SaugbaU, Chester CHI 6EN; teI. 01244 880018. E-mail: 4it A '&ee!I 1--pllk Contributions are welcome: (a) as e-mails or e-mail attachments; (b) a bard copy ofa computer file; (c) a typed :manuscript; (d) a hand-written manuscript, preterably wi1h a eontact 1elephone number so that any queries can be sorted out; (e) a CD/DVD; (f) a USB storage flash drive. Any queries to the Editor, please. The NEXT ISSUE will be dated June 2012, and contributions should get to the Editor as soon as possible, but at least before 1May2012. 11111111111111111111111111111111111111111.111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111 Copies ofthis magazine are aJso available to non-members: a cheque for f8 (payable to 'Barrow.more Model Railway Group') will provide the nm fuur issues. posted direct to your home. Send your details and cheque to the Editor at the above address. I I I 11 I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I f I I 11 I I I I I I I I I I I Tile cover Wustration for this issue is ofa private owner coal wagon operated by the local firm ofW.BDobell & Co.Ltd. This wagon is only one of several Dobell wagons which appear on the negative~ taken on 3 August 1912, in a sic.ting at Ellesmere Port docks. -

2021 Book News Welcome to Our 2021 Book News

2021 Book News Welcome to our 2021 Book News. As we come towards the end of a very strange year we hope that you’ve managed to get this far relatively unscathed. It’s been a very challenging time for us all and we’re just relieved that, so far, we’re mostly all in one piece. While we were closed over lockdown, Mark took on the challenge of digitalising some of Venture’s back catalogue producing over 20 downloadable books of some of our most popular titles. Thanks to the kind donations of our customers we managed to raise over £3000 for The Christie which was then matched pound for pound by a very good friend taking the total to almost £7000. There is still time to donate and download these books, just click on the downloads page on our website for the full list. We’re still operating with reduced numbers in the building at any one time. We’ve re-organised our schedules for packers and office staff to enable us to get orders out as fast as we can, but we’re also relying on carriers and suppliers. Many of the publishers whose titles we stock are small societies or one-man operations so please be aware of the longer lead times when placing orders for Christmas presents. The last posting dates for Christmas are listed on page 63 along with all the updates in light of the current Covid situation and also the impending Brexit deadline. In particular, please note the change to our order and payment processing which was introduced on 1st July 2020. -

Pullman Car Services - Archive

Pullman Car Services - Archive Pullman & CIWL News “The Quality of Service is Remembered Long After The Price is Forgotten” November & December 2014 Edition No.21. Pullman & La Compagnie Internationale des Wagons-Lits et des Grand Express Européens News Edition No.21 - November & December 2014 - Page 1 of 67 COVER PHOTOGRAPH - Graham Hallett. A rare view of a Pullman car at Gloucester Central Station in July 1971. Mk1 Pullman Kitchen Second No.345. The car was broken-up at King, Snailwell in 1980. From The Coupé. Welcome aboard your bi-monthly newsletter. I take this opportunity to thank those readers who have kindly taken time to forward contributions in the form of articles and images for this edition. I remain dependent on contributions of news, articles and ‘jpg’ format images in all aspects of Pullman and CIWL operations both past, present, future and of course aspects of both within the model railway interests. In the event you have anything that you wish to contribute to the next edition the editorial deadline date of Tuesday December 30th, nd with the scheduled publication date of Friday January 2 2015. All I ask of you for the time I spend in producing your newsletter, is for you to forward on by either E-mail or printing a copy, to any one you believe would be interested in reading matters Pullman & CIWL. Changing your Email address, or wish to be removed from the mailing list, please send an Email to the [email protected] with your request, it’s as simple as that. Publication of this newsletter will be on or about the 1st of January, March, May, July, September and November. -

WRF NL192 July 2018

WELLS RAILWAY FRATERNITY Newsletter No.192 - July 2018 th <<< 50 ANNIVERSARY YEAR >>> www.railwells.com Thank you to those who have contributed to this newsletter. Your contributions for future editions are welcome; please contact the editor, Steve Page Tel: 01761 433418, or email [email protected] < > < > < > < > < > < > < > < > < > < > < > < > < > < > < > < > < > < > < > < > < > < > < > < > Visit to STEAM Museum at Swindon on 12 June. Photo by Andrew Tucker. MODERNISATION TO PRIVATISATION, 1968 - 1997 by John Chalcraft – 8 May On the 8th May we once more welcomed John Chalcraft as our speaker. John has for many years published railway photographs and is well known for his knowledge on topics relating to our hobby. He began by informing us that there were now some 26,000 photographs on his website! From these, he had compiled a presentation entitled 'From Modernisation to Privatisation', covering a 30-year period from 1968 (the year of the Fraternity's founding) until 1997. His talk was accompanied by a couple of hundred illustrations, all of very high quality, which formed a most comprehensive review of the railway scene during a period when the railways of this country were subjected to great changes. We started with a few photos of the last steam locomotives at work on BR and then were treated to a review of the new motive power that appeared in the 20 years or so from the Modernisation Plan of 1955. John managed to illustrate nearly every class of diesel and electric locomotive that saw service in this period, from the diminutive '03' shunter up to the Class '56' 3,250 hp heavy freight locomotive - a total of over 50 types. -

THE CORKSCREW Newsletter of the Wimborne Railway Society

THE CORKSCREW Newsletter of the Wimborne Railway Society Founded 1975 Issue 108 December 2018 Guest locomotive No 3 was ex LMS Princess Coronation Pacific No 46233 "Duchess of Sutherland". She is seen departing Corfe Castle on Saturday 13th October, during a short spell of sunshine. In the main, weather during the Gala wasn't that brilliant. Colin Stone Visiting the SR courtesy of Ian Riley Engineering, and undoubted star of the Gala was "Black 5" No 44871. In this shot she is departing Corfe Castle with the demonstration Freight Train. Usually these freights contribute nothing to the railway's coffers, but on this occasion brake van rides were on offer at £5 per head. Hence as the time table "slipped" these "paying" services couldn't be dropped to allow a bit of catch up. Colin Stone WIMBORNE RAILWAY SOCIETY COMMITTEE. Chairman :- ...Barry Moorhouse…Vice Chairman :-...Jim Henville Secretary :- …Clive Finder... Membership:-...Martin Catford. Treasurers :- … Mike Wescombe and Bob Steedman George Russell.....Graham Bevan….Peter Watson...David Brealey The Corkscrew team......Editor..Ken Aveyard....Production..Colin Stone Download The Corkscrew from www.wimrail.org.uk Contact The Corkscrew at kenaveyardATyahoo.co.uk (replace AT with @) …...................................................................................................................... Editorial Once again we come around to the end of the year and hopefully this issue of The Corkscrew will be available at the Annual General Meeting on 6 December 2018. My thanks as always to those members who have submitted items for The Corkscrew during the year. Whether you are one of our more prolific writers or have submitted just a single article or photograph your contributions are most welcome. -

List of Drawings.Xlsx

Pullman Car Company Drawings List Description: 2441 engineering drawings in 101 rolls, related to the construction and maintenance of Pullman carriages. System of Arrangement: The original order of the collection has been lost. The drawings have therefore been listed as boxed. Physical Characteristics: The drawings are largely copy tracings on paper or linen. There are some drawings in pencil on cartridge paper and tracing paper and occasionally other copying processes, such as ozalid on plastic film, are evident. Administrative/Biographical History: The Pullman Company Ltd was formed in Britain in 1882, based on the Pullman concept of luxury rail travel in the United States and established under US licence and control. The idea of the Pullman car had already been introduced to the UK by the Midland Railway, with a specially chartered train taking a party of people on a tour of England and Scotland in 1876. The Midland railway imported 37 cars and erected them at their Derby Works. They ran them on contract until 1888. Other railway companies also experimented with Pullman services, but gradually developed their own improved rolling stock and ceased their contracts with Pullman. In 1905 the business was transferred to UK control under the chairmanship of Lord Dalziel, and in 1915 was re-founded as the Pullman Car Company Limited. Following the formation of the UK based company production of coaching stock was gradually moved to the UK. A small number of vehicles were manufactured by the Pullman Car Company’s own workshops at Preston Park in Brighton. The majority were built by private manufacturers such as the Birmingham Carriage and Wagon Company, Cravens of Sheffield, the Clayton Wagon Company of Lincoln, the Midland Carriage and Wagon Company and the Metropolitan Carriage and Wagon Company (later Metropolitan-Cammell). -

Milepost 30½ – October 2009

30 MILEPOST OCTOBER 2009 II SURELY, IT’S NOT 50 YEARS AGO ...... 60007 RETURNS TO YORK- Page 224 Photo: Bruce Nathan RPS railway performance society www.railperf.org.uk 30TH YEAR OF PUBLICATION Milepost 30½ – October 2009 The Quarterly Magazine of the Railway Performance Society Honorary President: Gordon Pettit, OBE, FCILT Commitee: CHAIRMAN Frank Collins 10 Collett Way, Frome, Somerset BA11 2XR Tel: 01373 466408 e-mail [email protected] SECRETARY & VC Martin Barrett 112 Langley Drive, Norton, Malton, N Yorks, YO17 9AB (and meetings) Tel: 01653 694937 Email: [email protected] TREASURER Peter Smith 28 Downsview Ave, Storrington, W Sussex, RH20 (and membership) 4PS. Tel 01903 742684 e-mail: [email protected] EDITOR David Ashley 92 Lawrence Drive, Ickenham, Uxbridge, Middx, UB10 8RW. Tel 01895 675178 E-mail: [email protected] Fastest Times Editor David Sage 93 Salisbury Rd, Burton, Christchurch, Dorset, BH23, 7JR. Tel 01202 249717 E-mail [email protected] Distance Chart Editor Ian Umpleby 314 Stainbeck Rd, Leeds, W Yorks LS7 2LR Tel 0113 266 8588 Email: [email protected] Database/Archivist Lee Allsopp 2 Gainsborough, North Lake, Bracknell, RG12 7WL Tel 01344 648644 e-mail [email protected] Technical Officer David Hobbs 11 Lynton Terrace, Acton, London W3 9DX Tel 020 8993 3788 e-mail [email protected] David Stannard 26 Broomfield Close, Chelford, Macclesfield, Cheshire,SK11 9SL. Tel 01625 861172 e mail: [email protected] Publicity/Webmaster Baard Covington, 2 Rose Cottage, Bradfield,Wix, Manningtree, Essex CO11 2SH Tel 07010 717717, E-mail: [email protected] Steam Specialist Michael Rowe Burley Cottage, Parson St., Porlock,Minehead, Somerset, TA24 8QJ . -

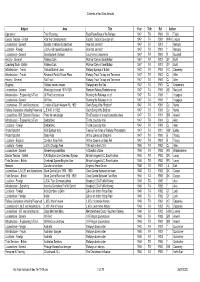

Ian Allan Annuals Index 14-12-09.Xlsx 1 of 29 26/01/2020 Contents of Ian Allan Annuals

Contents of Ian Allan Annuals Subject Area Title Year Title Ref Author Operations Train Planning Back Room Boys of the Railway 1947 TA Y901 M Taylor Electric Traction - British Post War Developments Electric Traction Development 1947 TA Y901 HWA Linecar Locomotives - General Speeds of various locomotives How fast on rails? 1947 TA Y901 * Mercury Locations - Foreign U.S.A. High speed locomotives How fast on rails? 1947 TA Y901 * Mercury Locomotives - General Development of shape Locomotive Lineaments 1947 TA Y901 R Bucknall History - General Pullman Cars Pullman Cars in Great Britain 1947 TA Y901 GF Burtt Coaching Stock - British Pullman Cars Pullman Cars in Great Britain 1947 TA Y901 GF Burtt Infrastructure - Tracks Various Branch Lines Railway Byways of Britain 1947 TA Y901 HC Casserley Infrastructure - Tracks Review of Past & Future Plans Railway Track To-day and Tomorrow 1947 TA Y901 CJ Allen History - General Rail Track Railway Track To-day and Tomorrow 1947 TA Y901 CJ Allen Shipping Railway owned vessels Railways and the Sea 1947 TA Y901 CJ Grasemann Locomotives - General Workings in period 1910-1920 Random Railway Reminiscences 1947 TA Y901 AB MacLeod Infrastructure - Engineering & Tech. Oil Fired Locomotives Running the Railways on oil 1947 TA Y901 * Voyageur Locomotives - General Oil Fired Running the Railways on oil 1947 TA Y901 * Voyageur Locomotives - S.R. and Absorbsions London & South Western Rly. 1922 Swan Song of the "Brighton" 1947 TA Y901 OJ Morris Railway Companies including Preserved L.S.W.R. in 1922 Swon Song of the Brighton 1947 TA Y901 OJ Morris Locomotives - B.R. Standard Classes Plans for new design The Evolution of a new locomotive class 1947 TA Y901 BW Anwell Infrastructure - Engineering & Tech. -

The Evolution of British Railways 1909-2009

The Evolution of British Railways 1909-2009 Britain’s Railways and The Railway Study Association 1909-2009 previously published in 2009 as part of A Century of Change 2019 Introduction to Second Edition Mike Horne FCILT MIRO This book was originally published by the name of ‘A Century of Change’ to commemorate the centenary of the Railway Study Association (RSA) in 1909; the Association is now the Railway Study Forum of the Chartered Institute of Logistics and Transport. Plenty has already been written about the railways of Britain. When the time came to celebrate the activities of the RSA, it occurred to this author that there was something missing. I felt that although it is self-evident that the railway today is very different to that of a century ago, the real point was that railways have been in a state of constant evolution, in part to respond to the changing conditions of the country and in part because of technological change. More importantly, this change will continue. Few people entering the in- dustry today can have much conception of what these changes will be, but change there will be: big changes too. What I wanted to highlight is the huge way the railway has altered, particularly in its technology and operational practices. This has happened, with great success, under diffi cult political and fi nancial conditions. Although the railway has lost much of its market share, the numbers of people carried today have recovered dramatically, and the fact this has been done on a much smaller system is an in- credible achievement that needs to be promoted. -

Pullman Car Services

PULLMAN CAR SERVICES The Quality of Service is Remembered Long after the Price is Forgotten ©J.Howard-Turner Collection/Antony M Ford Collection. PADUA as photographed by BRC&W Co Ltd, on completion prior to delivery. Pullman Car Services-Archive - PADUA - Issue 2 - June 2017 Page 1 of 24 Pullman Identity: PADUA. Type of Car: Parlour First Class. Into Service: October 1920. Builder: Birmingham Carriage & Wagon Company, Limited, Smethwick, Birmingham. Pre 1960 Schedule No: 99. Post 1960 Schedule No: 99. Tare: 40t. Seats: 26 (layout 1 x 1) = 2 x Saloon 8 & 10 & 2 x Coupe 4 = 8. On conversion to Second class in 1946, seating increased to 38 (layout 2 x 1) = 2 x Saloon 11 x 15 & 2 x Coupe 6 = 12. 1947 seating reduced to 36. Bogies: 2 x 6 wheels. Brake: Vacuum. Length (over Vestibules): 63’ 6”. Extreme Width: 8’ 7”. Roof: Ellongated. 1 Type 1932 List: ‘B’ 1921 to 1932 / ‘H’ from 1932. 2 Route Restriction (SR): 4/2A. Table Lamps Type: ‘D’ Type. Cost: £4,700. 1 Entries such as B/H indicate that the car was originally (old) type B, and was re-classified as Type H about 1932. 2 Entries such as 4/2A indicates that the car concerned was not originally given a S.R. Route Restriction because it was not originally allocated to the S.R.; and that it was given Restriction 2A on being transferred to the S.R. Interior: The car is decorated in inlaid mahogany in the Sheraton style, the carpets and upholstery being light green. Pullman Car Services-Archive - PADUA - Issue 2 - June 2017 Page 2 of 24 ©Antony M Ford.