Kettering General Hospital NHS Foundation Trust

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Open Space Supplementary Planning Document

Open Space Supplementary Planning Document November 2011 If you would like to receive this publication in an alternative format (large print, tape format or other languages) please contact us on 01832 742000. Page 2 of 25 Contents Page 1.0 Introduction 4 2.0 Purpose 4 3.0 Policy context and statutory process 4 4.0 Consultation 5 5.0 What is Open Space 5 6.0 When will open space need to be provided? 7 7.0 Calculating Provision 8 8.0 Implementing the SPD 9 Appendices: Appendix A – Glossary of Terms 10 Appendix B – Policy Context 11 Appendix C – Open Space Principles 12 Appendix D – Recommended Local Standards 15 Appendix E – A guide for the calculation of open space 17 Appendix F – Open Space requirements for Non-Residential 19 Developments Appendix G – Specification of local play types for children and young 20 people Appendix H – Flow Charts 22 Appendix I – List of Consultees 24 Page 3 of 25 1.0 Introduction 1.1 Open space can provide a number of functions: the location for play and recreation; a landscape buffer for the built environment; and provide an important habitat for biodiversity. It can also provide an attractive feature, which forms a major aspect of the character of a settlement or area. 1.2 In 2005, PMP consultants carried out an Open Space, Sport and Recreational Study of East Northamptonshire (published January 2006). In accordance with Planning Policy Guide (PPG) 17, the study identified open space and rated it on quality, quantity and accessibility issues, as well as highlighting areas of deprivation and where improvements to existing open space needed to be made. -

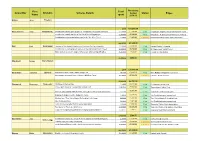

Councillor First Name Division Scheme Details Total Spent Status

First Total Remaining Councillor Division Scheme Details budget Status Payee Name spent 2009-10 Bailey John Finedon £0.00 £10,000.00 Beardsworth Sally Kingsthorpe Contribution towards play equipment - Kingsthorpe Play Builders Project £2,500.00 £7,500.00 Paid Kingsthorpe Neighbourhood Management Board Contribution towards the hire of the YMCA Bus in Kingsthorpe £1,500.00 £6,000.00 Paid Kingsthorpe Neighbourhood Management Board Contribution to design & printing costs for the 'We Were There' £100.00 £5,900.00 In progress Northamptonshire Black History Association £4,100.00 £5,900.00 Bell Paul Swanspool Opening of the Daylight Centre over Christmas for the vulnerable £1,500.00 £8,500.00 Paid Daylight Centre Fellowship Contribution to employing a p/t worker at Wellingborough Youth Project £2,800.00 £5,700.00 Paid Wellingborough Youth Project Motor skills develoment equipment for people with learning difficulties £5,250.00 £450.00 Paid Friends of Friars School £9,550.00 £450.00 Blackwell George Earls Barton £0.00 £10,000.00 Boardman Catherine Uplands New kitchen floor - West Haddon Village Hall £803.85 £9,196.15 Paid West Haddon Village Hall Committee New garage doors and locks - Lilbourne Mini Bus Garage £3,104.65 £6,091.50 In progress Lilbourne Parish Council £3,908.50 £6,091.50 Bromwich Rosemary Towcester A5 Rangers Cycling Club £759.00 £9,241.00 Paid A5 Rangers Cycling Club Cricket pitch cover for Towcestrians Cricket Club £1,845.00 £7,396.00 Paid Towcestrians Cricket Club £6,861.00 Home & away playing shirts for Towcester Ladies Hockey -

List of Mayor/Deputy Mayor's Engagements

List of Mayor’s/Deputy Mayor’s engagements 2010/2011 Mayor: Councillor Ann Brown Deputy: Councillor John McGhee Date Event Location Mayor Deputy Refused 23 May 10 Lakelands Legs Walk Lakelands Hospice √ 23 May 10 Wellingborough Civic Service All Saints Church, Wellingborough √ ‘Photo with the Mayor’ 28 May 10 Rhyme time Nursery, Corby Challenge √ United Reformed Church, Fox Street, 30 May 10 Rothwell Civic Service Rothwell √ Rothwell Ancient Street Fair 31 May 10 Parish Church/Rothwell Town Centre (806th Proclamation) √ British Army Recruitment 3 June 10 Corporation Street, Corby Office Opening √ 6 June 10 Big Red Ramble ECP √ 6 June 10 Cadet 150 Celebration St George’s Barracks, North Luffenham √ Desborough TC Charity 6 June 10 116 Harborough Road, Desborough Lunch √ High Sheriff 10 June 10 Northamptonshire – Garden Fermyn Woods Hall √ Party 11 June 10 Spirit of Corby Awards Holiday Inn, Corby √ 2018 World Cup Celebration 12 June 10 Stadium Milton Keynes Dinner √ Let’s Dance – Rushden 12 June 10 St Peters Catholic Church Hall, Rushden Charity Event √ Healthy Living and Lifestyle 12 June 10 Corby Town Centre Promotion Day √ 1 The Parish of All Saints with St John the 13 June 10 Stamford Civic Service Baptist, Stamford √ 13 June 10 Peterborough Civic Service Peterborough Cathedral √ 13 June 10 Kettering Civic Service SS Peter and Paul Church, Kettering √ NBC Charity Sunday + 13 June 10 All Saints Church Service √ 14 June 10 A Book Week Woodnewton Primary School √ 15 June 10 Radio Interview Corby Radio √ Opening of New Kingswood 15 June -

Part 1: National and Local Policy Context

WEST NORTHAMPTONSHIRE OPEN SPACE, SPORT AND RECREATION STRATEGIES FOR NORTHAMPTON BOROUGH Part 1: National and Local Policy Context Final Report March 2017 Nortoft Partnerships Limited 2 Green Lodge Barn, Nobottle, Northampton NN7 4HD Tel: 01604 586526 Fax: 01604 587719 Email: [email protected] Web: www.nortoft.co.uk TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION 1: PROFILE OF NORTHAMPTON 6 SECTION 2: THE POLICY FRAMEWORK 30 SECTION 3: STAKEHOLDER ENGAGEMENT 45 DRAFT West Northamptonshire: Northampton Borough Nortoft Partnerships Ltd Open Space, Sport & Recreation Strategies Page 2 of 58 Part 1: National and Local Policy Context TABLE OF FIGURES Figure 1: Northampton Related Development Area SUEs 8 Figure 2: Northampton current population structure compared to England 9 Figure 3: Growth across the Borough to 2029 10 Figure 4: Population growth in the NRDA SUEs 11 Figure 5: Northampton Borough population change 2016-29 12 Figure 6: NRDA population up to 2029 13 Figure 7: NRDA area change 2016-29 13 Figure 8: Multiple deprivation in Northampton 2015 15 Figure 9: Health Profile for Northampton 18 Figure 10: Sport and physical activity levels for adults 23 Figure 11: Top sports in Northampton with regional and national comparison 24 Figure 13: Market Segments 25 Figure 14: Largest market segments (whole authority) 26 Figure 15: Market Segmentation map - LSOA level 28 Figure 16: Market segmentation and interest in sport 29 Figure 17: NRDA Sustainable Urban Extension (SUE) Locations 36 Figure 18: Survey and demographics 47 Figure 19: Do you use these facilities -

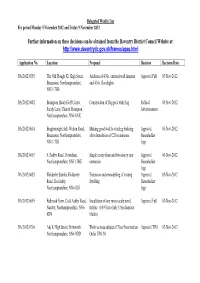

Further Information on These Decisions Can Be Obtained from the Daventry District Council Website At

Delegated Weekly List For period Monday 5 November 2012 and Friday 9 November 2012 Further information on these decisions can be obtained from the Daventry District Council Website at: http://www.daventrydc.gov.uk/frames/apas.html Application No. Location Proposal Decision Decision Date DA/2012/0355 The Old Plough 82, High Street, Addition of 4 No. external wall lanterns Approval Full 05-Nov-2012 Braunston, Northamptonshire, and 4 No. floodlights NN11 7HS DA/2012/0482 Brampton Heath Golf Centre, Construction of flag pole with flag Refusal 08-Nov-2012 Sandy Lane, Church Brampton, Advertisement Northamptonshire, NN6 8AX DA/2012/0614 Bragborough Hall, Welton Road, Making good wall to existing building Approval 05-Nov-2012 Braunston, Northamptonshire, after demolition of C20 extensions. Householder NN11 7JG App DA/2012/0619 5, Badby Road, Newnham, Single storey front and two storey rear Approval 06-Nov-2012 Northamptonshire, NN11 3HE extension Householder App DA/2012/0685 Holdenby Stables, Holdenby Extension and remodelling of exsting Approval 05-Nov-2012 Road, Holdenby, dwelling Householder Northamptonshire, NN6 8DJ App DA/2012/0695 Fulbrook Farm, Cold Ashby Road, Installation of one micro scale wind Approval Full 07-Nov-2012 Naseby, Northamptonshire, NN6 turbine (14.97m to hub, 5.5m diameter 6DN blades) DA/2012/0704 Adj 8, High Street, Brixworth, Work to trees subject of Tree Preservation Approval TPO 07-Nov-2012 Northamptonshire, NN6 9DD Order TPO 30 Delegated Weekly List For period Monday 5 November 2012 and Friday 9 November 2012 Further information on these decisions can be obtained from the Daventry District Council Website at: http://www.daventrydc.gov.uk/frames/apas.html Application No. -

NEWSLETTER July 2021

NEWSLETTER July 2021 Heritage Organisation of the Year won by Northampton Museum and Art Gallery Photograph courtesy of Laura Malpas and NMAG Northamptonshire Heritage Forum page 1 July 2021 www.northamptonshireheritageforum.co.uk MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIRMAN Thursday 1 July was a wonderful opportunity to celebrate the outstanding achievements of Northamptonshire heritage organisations. My congratulations to all the winners of the Awards and our other members that submitted entries. I was delighted that Northampton Museum and Art Gallery was awarded Organisation of the Year and I look forward to representing the Forum at its gala opening on Tuesday 20 July. The Vice Lord Lieutenant, James Lowther, encouraged the Forum and all its members to remember how important Heritage is to the recovery of the economy following the pandemic. Our partnership with Northants Surprise will facilitate improved visitor information about our historic houses, sites and museums and I am sure we will all make the best of this opportunity to recover and grow our audiences. Issue 27 of Hindsight has been published and will be with you shortly, if you haven’t already received your copy. I am sure everyone will enjoy reading the very varied articles; they represent the best of heritage in Northamptonshire. Finally, I wish you all the best with your activities over the coming months. Martin Lawrence MBE WEBSITE UPDATE The new Northamptonshire Heritage Forum website is now up and running. We hope that you have been able to have a look at it, and for any organisations who have not yet checked their details, please do so, as soon as possible. -

Landscape Character Assessment Current

CURRENT LANDSCAPE CHARACTER ASSESSMENT CONTENTS CONTENTS 02 PREFACE 04 1.0 INTRODUCTION 06 1.1 Appointment and Brief 06 1.2 Northamptonshire Environmental Characterisation Process 06 1.3 Landscape Characterisation in Practice 06 1.4 Northamptonshire Current Landsacape Character Assessment 07 1.5 Approach and Methodology 07 1.6 The Scope and Context of the Study 08 1.7 Parallel Projects and Surveys 08 1.8 Structure of the Report 09 2.0 EVOLUTION OF THE LANDSCAPE 10 2.1 Introduction 10 Physical Influences 2.2 Geology and Soils 10 2.3 Landform 14 2.4 Northamptonshire Physiographic Model 14 2.5 Hydrology 15 2.6 Land Use and Land Cover 16 2.7 Woodland and Trees 18 2.8 Biodiversity 19 2.85 Summary 22 2.9 Buildings and Settlement 23 2.10 Boundaries 25 2.11 Communications and Infrastructure 26 2.12 Historic Landscape Character 28 3.0 NORTHAMPTONSHIRE’S CURRENT LANDSCAPE CHARACTER 29 Cowpasture Spinney, Rolling Ironstone Valley Slopes 3.1 Introduction 29 3.2 Landscape Character Types and Landscape Character Areas 30 3.3 Landscape Character Type and Area Boundary Determination 30 CURRENT LANDSCAPE CHARACTER ASSESSMENT 2 CONTENTS 4.0 GLOSSARY 187 4.1 Key Landscape Character Assessment Terms 187 4.2 Other Technical Terms 187 4.3 Abbreviations 189 5.0 REFERENCES 190 6.0 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 191 APPENDICES View over arable land, Limestone Plateau Appendix 1 Data Sets Used in the Northamptonshire Current Landscape Character Assessment Appendix 2 Example of Digital Field Survey Forms Appendix 3 Field Work Prompts Sheets and Mapping Prompts Sheet Appendix -

MINUTES of BADBY ANNUAL PARISH MEETING HELD in the VILLAGE HALL at 7.00 P.M. on MONDAY 11TH MAY 2009 7 Parishioners Attended

MINUTES OF BADBY ANNUAL PARISH MEETING HELD IN THE VILLAGE HALL AT 7.00 P.M. ON MONDAY 11TH MAY 2009 7 parishioners attended the meeting, with the Chairman of the Parish Council, Mr Mike Richards, in the chair. Also in attendance were Parish Councillors Mrs Karen Alexander, Mr Peter Banks, Mrs Sheila Gillings, Mrs Sally Halson, Mr Steve Robson and Mr Mike Warburton; Parish Clerk, Mrs Sharon Foster and PCSO Sarah Gray. 1. APOLOGIES These were received from County Councillor Robin Brown and District Councillor Tony Scott. 2. APPROVAL OF MINUTES It was proposed by D Wilson, seconded by M Warburton and agreed that the minutes of the Annual Parish Meeting on 12th May 2008 should be signed by the Chairman as a true record of that meeting. 3. REPORT BY COUNTY COUNCILLOR In the absence of County Councillor Robin Brown, Mike Richards read out his report. This report marks the final year of the current administrations period in control of the County Council, elections for a new term take place on the 4th June 2009.The last twelve months have been both frustrating yet in some ways very rewarding. The frustration continues to be caused by the exceedingly slow way that change is enacted within the Council. The rewards are that there is evidence of a different culture and attitude from the Council and a greater commitment to put the needs of the customers, us the residents, first. There is now a new team of executives managing the Council resources with a clear remit to be improving services whilst reducing cost. -

King's School, Peterborough; John

NORTHAMPTONSHIRE PAST AND PRESENT 1975 CONTENTS PAGE Particulars of the Society ii Institutional Members of the Society ii Notes and News . 153 Joan Wake. G. !sham 156 Patrick King writes . 160 The Published Works of J oan Wake. Rosemary Eady 162 The Origins of the Wake Family: The Early History of the Barony of Bourne in Lincolnshire. E. King .. 167 Four Deserted Settlements in Northamptonshire. A. E. Brown; C. C. Taylor 178 The Fourteenth-Century Tile Paving at Higham Ferrers. Elizabeth S. Eames 199 The Medieval Parks of Northamptonshire. J. M. Steane 211 Helmdon Wills 1603-1760. E. Parry ... 235 Justices of the Peace in Northamptonshire 1830-1845. Part II. The Work of the County Magistrates. R. W. Shorthouse 243 The Rise of Industrial Kettering. R. L. Greenall ... 253 Domestic Service in Northamptonshire-1830-1914. Pamela Horn 267 King's School, Peterborough. A. Wootton 276 John Dryden's Titchmarsh Home. Helen Belgion ... 278 Book Reviews: J. M. Steane, Buildings of England: Northamptonshire 281 V. A. Hatley, 1873-1973, Mount Pleasant Chapel, Northampton: History 283 V. A. Hatley, Class Struggle and the Industrial Revolution: Early Industrial Capitalism in Three English Towns... 284 G. Isham, Theatre Unroyal ... 285 B. A. Holderness, Northants Militia Lists 1777 286 N. Marlow, The Northamptonshire Landscape: Northamptonshire and the Soke of Peterborough 287 Obituaries: Mrs. Philippa Mary Mendes-Da Costa 289 Mr. John Waters, R.J. Kitchin .. 289 All communications regarding articles in this issue and future issues should be addressed to the Honorary Editor, Mr.}. M. Steane, The Grammar School, Kettering Published by the Northamptonshire Record Society VoL. -

Northamptonshire Highway Asset Management Policy and Strategy

Northamptonshire Highway Asset Management Policy and Strategy Northamptonshire Highway Asset Management Policy and Strategy October 2015 1 Northamptonshire Highway Asset Management Policy and Strategy (Blank Page) 2 Northamptonshire Highway Asset Management Policy and Strategy Foreword It is with pleasure I present Northamptonshire County Council’s Highway Asset Management Policy and Strategy. This document brings together key policies and strategies to manage the significant number of assets we have on the Northamptonshire Highway Network and it supersedes historical Northamptonshire Asset Management Plans. The Northamptonshire highway network continues to grow year-on-year and we constantly look to refine and improve how we manage the highway assets to develop maintenance strategies which balance the demand on the network, available maintenance funding and public expectation. The importance of establishing and practicing a sound approach to asset management is recognised by the Department for Transport. The Highway Maintenance Efficiency Programme was established to assist Local Authorities with managing assets and more recently future highways funding allocations will reflect how well a Local Authority practices asset management. The Highway Asset Management Policy and Strategy document is supplemented by other key documents including the Highway Network Management Plan and the Northamptonshire Transport Plan. Furthermore the Highway Infrastructure Asset management Plan supports the Northamptonshire County Councils corporate objectives including contributing to and increasing the well-being of our citizens and making Northamptonshire a great place to live and work through creating and maintaining safe, inclusive and functional highways. Councillor Michael Clarke Cabinet Member for Transport, Highways and Environment 3 Northamptonshire Highway Asset Management Policy and Strategy (Blank Page) 4 Northamptonshire Highway Asset Management Policy and Strategy Contents Chapter Theme & Content Page No. -

Open Space, Sport and Recreation Needs Assessment and Audit An

Northampton Borough Council Open Space, Sport and Recreation Needs Assessment and Audit An Update Report by PMP September 2009 CONTENTS Page Section 1 Introduction & background 1 Section 2 Undertaking the study 5 Section 3 Strategic context 15 Section 4 Parks and gardens 32 Section 5 Natural and semi natural 57 Section 6 Amenity green space 78 Section 7 Provision for children and young people 98 Section 8 Outdoor sports facilities 142 Section 9 Indoor sports facilities 168 Section 10 Allotments 188 Section 11 Cemeteries and churchyards 201 Section 12 Green corridors and green infrastructure 210 Section 13 Northampton Central Area & Civic Spaces 222 SECTION 1 INTRODUCTION & BACKGROUND SECTION 1 – INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND Introduction and background The study 1.1 During February 2009 Northampton Borough Council appointed PMP to undertake an open space, sport and recreation needs assessment and audit across Northampton Borough. The study builds upon work undertaken by PMP in 2006 and evaluates needs and opportunities for current and future provision. 1.2 The findings of this work will enable the Council to adopt a clear vision for the future delivery of open space, sport and recreation facilities and provide evidence for informed decision making. 1.3 The study will form part of the evidence base for the Local Development Framework (LDF) and will contribute to the formulation of the parks and open spaces strategy. 1.4 The objectives of the study are as follows: • update the audit to reflect recent changes • develop new local standards to reflect the updated audit • reapply the local standards to help identify the key priorities in the borough • inform the future management of open spaces and facilitate decision making on the current and future needs for open space, sport and recreation facilities. -

South Northamptonshire Local Plan Part 2 2011-2029

South Northamptonshire Part 2 Local Plan 2011-2029 South Northamptonshire Local Plan (Part 2) Foreword South Northants is a great place to live, work and invest, with its two successful market towns, of Brackley and Towcester, the dynamic Silverstone circuit supporting the High Performance Technology and Motorsport Engineering sector, a wonderful landscape and villages, many of which contain conservation areas, reflecting the history and heritage that is the foundation of the District. The Local Plan embraces that backdrop and seeks to ensure any new development is good development in the right locations to support growth. This Local Plan for South Northants builds on the West Northamptonshire Joint Core Strategy, by adding local detail including looking at the sustainability of our villages and providing a settlement hierarchy. The plan also reviews and reinstates confines for all the main villages across the District, to ensure they can grow in an appropriate way and proper scale. The Plan contains a series of new policies to guide the construction of all types of housing, such as starter homes, self-build and homes for older people to ensure greater housing choice is provided for all local residents. We want to support small scale appropriate local housing growth in accordance with the NPPF, in addition to the large housing sites that are under construction at Radstone Fields, Brackley, Towcester South and the edge of Northampton, This Plan sets out how. As a council we recognise that a strong economy is at the heart of our quality of life and the policies in the plan seek to retain the employment land we have as well as to increase the supply of new employment sites.