Northamptonshire Past and Present, No 58

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notice of Uncontested Elections

NOTICE OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION West Northamptonshire Council Election of Parish Councillors for Arthingworth on Thursday 6 May 2021 I, Anna Earnshaw, being the Returning Officer at the above election, report that the persons whose names appear below were duly elected Parish Councillors for Arthingworth. Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) HANDY 5 Sunnybank, Kelmarsh Road, Susan Jill Arthingworth, LE16 8JX HARRIS 8 Kelmarsh Road, Arthingworth, John Market Harborough, Leics, LE16 8JZ KENNEDY Middle Cottage, Oxendon Road, Bernadette Arthingworth, LE16 8LA KENNEDY (address in West Michael Peter Northamptonshire) MORSE Lodge Farm, Desborough Rd, Kate Louise Braybrooke, Market Harborough, Leicestershire, LE16 8LF SANDERSON 2 Hall Close, Arthingworth, Market Lesley Ann Harborough, Leics, LE16 8JS Dated Thursday 8 April 2021 Anna Earnshaw Returning Officer Printed and published by the Returning Officer, Civic Offices, Lodge Road, Daventry, Northants, NN11 4FP NOTICE OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION West Northamptonshire Council Election of Parish Councillors for Badby on Thursday 6 May 2021 I, Anna Earnshaw, being the Returning Officer at the above election, report that the persons whose names appear below were duly elected Parish Councillors for Badby. Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) BERRY (address in West Sue Northamptonshire) CHANDLER (address in West Steve Northamptonshire) COLLINS (address in West Peter Frederick Northamptonshire) GRIFFITHS (address in West Katie Jane Northamptonshire) HIND Rosewood Cottage, Church -

The London Gazette, 25 March, 1955 1797

THE LONDON GAZETTE, 25 MARCH, 1955 1797 Type of Reference No. Parish path on Map Description of Route Sibbertoft Footpath . D.N. 3 From the north boundary of O.S. Plot 154, southwards across O.S. Plot 154 to the county road at The Manor, Sibbertoft. Sulby Footpath ... D.R. 2 From the west boundary of O.S. Plot 18, in a north-east direction across the site of the Polish Hostel to the north- east corner of O.S. Plot 18. Thornby Footpath ... D.S.3 From the Thornby-Great Creaton road at the south-east end of Thornby village, southwards to the Guilsborough parish boundary north of Nortoft Lodge Farm. Footpath ... D.S. 5 From the Winwick-Thornby road, east of Thornby Grange adjoining Rabbit Spinney, eastwards to the Thornby- Guilsborough road at the Guilsborough parish boundary. Walgrave Footpath ... D.T. 12 From the Walgrave-Broughton road at the east end of Walgrave village, north-eastwards to the Old-Broughton road, north-east of Red Lodge Farm. THE SECOND SCHEDULE Rights of way to be added to the draft maps and statements Type of Reference No. Parish path on Map Description of Route \rthingworth ... Footpath ... C.B. 5 From the Great Oxendon-Braybrooke road, southwards via Round Spinney to county road at junction with C.B. 4. frington Bridleway ... C.F. 20 From the Nobottie-Duston road at the east end of Nobottle village, south-eastwards to the Harpole parish boundary, east of Brices Spinney. riipston Footpath ... C.H. 22 From the junction of C.H. 19 and C.H. -

Open Space Supplementary Planning Document

Open Space Supplementary Planning Document November 2011 If you would like to receive this publication in an alternative format (large print, tape format or other languages) please contact us on 01832 742000. Page 2 of 25 Contents Page 1.0 Introduction 4 2.0 Purpose 4 3.0 Policy context and statutory process 4 4.0 Consultation 5 5.0 What is Open Space 5 6.0 When will open space need to be provided? 7 7.0 Calculating Provision 8 8.0 Implementing the SPD 9 Appendices: Appendix A – Glossary of Terms 10 Appendix B – Policy Context 11 Appendix C – Open Space Principles 12 Appendix D – Recommended Local Standards 15 Appendix E – A guide for the calculation of open space 17 Appendix F – Open Space requirements for Non-Residential 19 Developments Appendix G – Specification of local play types for children and young 20 people Appendix H – Flow Charts 22 Appendix I – List of Consultees 24 Page 3 of 25 1.0 Introduction 1.1 Open space can provide a number of functions: the location for play and recreation; a landscape buffer for the built environment; and provide an important habitat for biodiversity. It can also provide an attractive feature, which forms a major aspect of the character of a settlement or area. 1.2 In 2005, PMP consultants carried out an Open Space, Sport and Recreational Study of East Northamptonshire (published January 2006). In accordance with Planning Policy Guide (PPG) 17, the study identified open space and rated it on quality, quantity and accessibility issues, as well as highlighting areas of deprivation and where improvements to existing open space needed to be made. -

East Midlands

TVAS EAST MIDLANDS Land at Washpit House, Grafton Road, Brigstock, Northamptonshire Archaeological Watching Brief by Josh Hargreaves and Eleanor Boot Site Code: GRB20/140 (SP 9423 8294) Land at Washpit House, Grafton Road, Brigstock, Northamptonshire Archaeological Earthwork Survey and Watching Brief For Mr Dan Kantorovich By Joshua Hargreaves and Eleanor Boot TVAS East Midlands GRB 20/140 February 2021 Summary Site name: Land at Washpit House, Grafton Road, Brigstock, Northamptonshire Grid reference: SP 9423 8294 Site activity: Earthwork Survey and Watching Brief Date and duration of project: 26th – 30th November 2020 Project coordinator: Steve Ford Site supervisor: Joshua Hargreaves Site code: GRB 20/140 Event numbers: ENN109995 and ENN109996 Area of site: c. 9860 sq m Summary of results: The earthwork survey showed evidence of a slight sunken trackway running N-S towards the remains of a medieval dam and post-medieval causeway. It further mapped the slope of natural valley sides. The observation of ground reduction works revealed a bank revetment probably relating to the medieval hunting lodge and its pond (The Great Pond). A large post-medieval quarry pit was also observed and part investigated. Location and reference of archive: The archive is presently held at TVAS East Midlands, Wellingborough and will be deposited at the Northamptonshire Archives Store in due course. This report may be copied for bona fide research or planning purposes without the explicit permission of the copyright holder. All TVAS unpublished fieldwork reports -

List of Pharmacies Providing Cover for New Year 2015/16 in Northamptonshire

List of Pharmacies providing cover for New Year 2015/16 in Northamptonshire New Year's Eve New Year's Day Sat 2nd Jan 2016 NORTHAMPTON Abington Pharmacy 51F Beech Avenue Northampton NN3 2JG UOH Closed UOH Allisons Pharmacy 56 Kingsley Park Terrace Northampton NN2 7HH UOH Closed UOH Balmoral Pharmacy Queensview Medical Centre Thornton Road Northampton NN2 6LS UOH 10:00 - 14:00 UOH Boots Pharmacy 30 Weston Favell Centre Northampton NN3 8JZ UOH Closed UOH Boots Pharmacy Unit D Sixfields Retail Park 31 Gambrel Road Northampton NN5 5DG UOH 10:00 - 16:00 UOH Boots Pharmacy 9 The Parade Grosvenor Centre Northampton NN1 2BY UOH 10:00 - 17:00 UOH Boots Pharmacy 1-2 Alexandra Terrace Harborough Road, Kingsthorpe Northampton NN2 7SJ UOH Closed UOH Boots Pharmacy 16 Fairground way Riverside Business Park Northampton NN3 9HU 09:00 - 17:30 10:30 - 16:30 UOH Boots Pharmacy Unit 7 St James Retail Park Towcester Road Northampton NN1 1EE UOH 10:30 - 16:30 UOH Brook Pharmacy Ecton Brook Road Northampton NN3 5EN UOH Closed UOH Delapre Pharmacy 52 Gloucester Avenue Northampton NN4 8QF UOH Closed UOH Far Cotton Pharmacy Delapre Crescent Road Northampton NN4 8LG UOH Closed UOH Imaan Pharmacy Unit 2-3 Blackthorn Local Centre Northampton NN3 8QH UOH Closed UOH Jhoots Pharmacy 42 Semilong Road Northampton NN2 6BU UOH Closed UOH Jhoots Pharmacy Wilks Walk Grange Park Northampton NN4 5DW UOH Closed UOH Limehurst Square Pharmacy 9 Limehurst Square, Duston Northampton NN5 6LP UOH Closed UOH Lloyds Pharmacy 10 Greenview Drive Northampton NN2 7LA UOH Closed UOH Lloyds -

Northampton Town Council Executive Committee

NORTHAMPTON TOWN COUNCIL EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE Tuesday, 19 January 2021 PRESENT: Councillor Birch (Chair); Councillor Marriott (Deputy Chair); Councillors Lane, B Markham, McCutcheon and Russell In attendance: Councillors Ashraf, Hallam, Hibbert and Stone with Mr R Walden (Acting Town Clerk), Ms M Goodman and Mr L Gould (Borough Council) and Dr L Sambrook-Smith (Northants CALC) 1. APOLOGIES FOR ABSENCE There were none. 2. MINUTES The minutes of the previous meeting held on 5th January 2021 were agreed as a true and accurate record of the meeting. 3. DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST There were none. 4. TRANSFER OF PROPERTY AND SERVICES The Acting Town Clerk recalled that over a period of time a wide range of properties and services had been suggested for possible transfer from the Borough Council to the new Town Council. These fell into three general categories: those which had already been agreed; those which the Borough had agreed to transfer in principle subject to further reports; and those in respect of which the Town Council had requested further information on the financial and staffing implications of transfer before considering further. a) Transfers already agreed The Statutory Order creating the Town Council had transferred the following allotment sites on 1st April 2021: Billing Road East, Broadmead Avenue, Glebeland Road, Graspin Lane, Harlestone Road, Parklands, Rothersthorpe Road and Southfields. The Order had also transferred the Mayoralty and accordingly the full current budget for mayoral support services is being included in the draft budget. A long list of other civic items including regalia, robes, muniments and other artefacts was being compiled and would be reported in due course. -

ORGANISATION ADDRESS NAME IF KNOWN EAST NORTHANTS COUNCIL East Northamptonshire House, Cedar Dr, Mike Burton – ENC Planning Thrapston, Kettering NN14 4LZ

ORGANISATION ADDRESS NAME IF KNOWN EAST NORTHANTS COUNCIL East Northamptonshire House, Cedar Dr, Mike Burton – ENC Planning Thrapston, Kettering NN14 4LZ NATURAL ENGLAND Natural England Andrew Sells – Chairman Block B, Government Buildings, Whittington Road Julie Danby Team Leader- Worcester [email protected] WR5 2LQ HISTORIC ENGLAND 2nd floor Windsor House Cliftonville Northampton NN1 5BE HEADMASTER Brigstock Latham's CE Primary School, Latham Mr Nick Garley (Headteacher) BRIGSTOCK SCHOOL Street, Brigstock, Kettering Northants NN14 3HD HEAD OF GOVERNORS c/o Brigstock Latham's CE Primary School, Latham Mr Tim Cullinan BRIGSTOCK SCHOOL Street, Brigstock, Mrs Abigail Marsden-Findlay - Kettering Northants NN14 3HD [email protected] DIOCESAN BOARD OF FINANCE The Palace/Minster Precincts, Peterborough PE1 1YB NENE VALLEY CATCHMENT PARTNERSHIP The Business Exchange Rockingham Rd Kettering NN16 8JX ENVIRONMENT AGENCY Waterside House Or Waterside North Lincoln Lincolnshire LN2 5HA Nene House Ketteriing Northants NN15 6JQ CLINICAL COMMISSIONING NHS Nene Clinical Commissioning Group Francis Crick House Summerhouse Road Moulton Park Northampton NN3 6BF WILDLIFE TRUST Lings House, off Lings Way Billing Lings Northampton NN3 8BE HOUSING ASSOCIATIONS Spire Homes 1 Crown Court, Crown Way, Rushden, Northamptonshire NN10 6BS RURAL HOUSING ASSOCIATION [email protected] Neil Gilliver ROCKINGHAM FOREST HOUSING ASSOCIATION [email protected] POLICE – East Northants North Police station Oundle Police Station Glapthorn -

Daventry District Council Weekly List of Applications Registered 01/07/2019

DAVENTRY DISTRICT COUNCIL WEEKLY LIST OF APPLICATIONS REGISTERED 01/07/2019 App No. DA/2019/0358 Registered Date 20/06/2019 Location 10, Little Close, Chapel Brampton, Northamptonshire, NN6 8AL Proposal Two storey rear extension and detached double garage Parish Church with Chapel Brampton, Chapel Brampton Case Officer Rebecca Hambridge Easting: 472671 Northing: 266281 UPRN 28022794 App No. DA/2019/0475 Registered Date 20/06/2019 Location Manor House Farm, Nortoft, Guilsborough, Northamptonshire, NN6 8QB Proposal Conversion of barn to dwelling including single storey extension (Revised scheme) Parish Guilsborough Case Officer Sue Barnes Easting: 467526 Northing: 273219 UPRN 28031638 App No. DA/2019/0500 Registered Date 25/06/2019 Location Grange Cottage, West Haddon Road, EAST HADDON, Northamptonshire, NN6 8DR Proposal Demolition of existing cottage and construction of two detached dwellings (Revised scheme) Parish East Haddon Case Officer S Hammonds Easting: 467257 Northing: 267082 UPRN 28019809 App No. DA/2019/0504 Registered Date 11/06/2019 Location Manor House, Main Street, Ashby St Ledgers, Northamptonshire, CV23 8UN Proposal Works to and removal of trees in a Conservation Area. Parish Ashby St Ledgers Case Officer Mr M Venton Easting: 457472 Northing: 268369 UPRN 28012253 App No. DA/2019/0506 Registered Date 24/06/2019 Location 22, St Johns Close, Daventry, Northamptonshire, NN11 4SH Proposal New front porch Parish Drayton Case Officer Rob Burton Easting: 456928 Northing: 261626 UPRN 28005148 App No. DA/2019/0509 Registered Date 17/06/2019 Location 2, Halford Way, Welton, Northamptonshire, NN11 2XZ Proposal Single storey rear extension and new front porch Parish Welton Case Officer Rebecca Hambridge Easting: 458219 Northing: 265925 UPRN 28013496 App No. -

Premises, Sites Etc Within 30 Miles of Harrington Museum Used for Military Purposes in the 20Th Century

Premises, Sites etc within 30 miles of Harrington Museum used for Military Purposes in the 20th Century The following listing attempts to identify those premises and sites that were used for military purposes during the 20th Century. The listing is very much a works in progress document so if you are aware of any other sites or premises within 30 miles of Harrington, Northamptonshire, then we would very much appreciate receiving details of them. Similarly if you spot any errors, or have further information on those premises/sites that are listed then we would be pleased to hear from you. Please use the reporting sheets at the end of this document and send or email to the Carpetbagger Aviation Museum, Sunnyvale Farm, Harrington, Northampton, NN6 9PF, [email protected] We hope that you find this document of interest. Village/ Town Name of Location / Address Distance to Period used Use Premises Museum Abthorpe SP 646 464 34.8 km World War 2 ANTI AIRCRAFT SEARCHLIGHT BATTERY Northamptonshire The site of a World War II searchlight battery. The site is known to have had a generator and Nissen huts. It was probably constructed between 1939 and 1945 but the site had been destroyed by the time of the Defence of Britain survey. Ailsworth Manor House Cambridgeshire World War 2 HOME GUARD STORE A Company of the 2nd (Peterborough) Battalion Northamptonshire Home Guard used two rooms and a cellar for a company store at the Manor House at Ailsworth Alconbury RAF Alconbury TL 211 767 44.3 km 1938 - 1995 AIRFIELD Huntingdonshire It was previously named 'RAF Abbots Ripton' from 1938 to 9 September 1942 while under RAF Bomber Command control. -

Wren and the English Baroque

What is English Baroque? • An architectural style promoted by Christopher Wren (1632-1723) that developed between the Great Fire (1666) and the Treaty of Utrecht (1713). It is associated with the new freedom of the Restoration following the Cromwell’s puritan restrictions and the Great Fire of London provided a blank canvas for architects. In France the repeal of the Edict of Nantes in 1685 revived religious conflict and caused many French Huguenot craftsmen to move to England. • In total Wren built 52 churches in London of which his most famous is St Paul’s Cathedral (1675-1711). Wren met Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598-1680) in Paris in August 1665 and Wren’s later designs tempered the exuberant articulation of Bernini’s and Francesco Borromini’s (1599-1667) architecture in Italy with the sober, strict classical architecture of Inigo Jones. • The first truly Baroque English country house was Chatsworth, started in 1687 and designed by William Talman. • The culmination of English Baroque came with Sir John Vanbrugh (1664-1726) and Nicholas Hawksmoor (1661-1736), Castle Howard (1699, flamboyant assemble of restless masses), Blenheim Palace (1705, vast belvederes of massed stone with curious finials), and Appuldurcombe House, Isle of Wight (now in ruins). Vanburgh’s final work was Seaton Delaval Hall (1718, unique in its structural audacity). Vanburgh was a Restoration playwright and the English Baroque is a theatrical creation. In the early 18th century the English Baroque went out of fashion. It was associated with Toryism, the Continent and Popery by the dominant Protestant Whig aristocracy. The Whig Thomas Watson-Wentworth, 1st Marquess of Rockingham, built a Baroque house in the 1720s but criticism resulted in the huge new Palladian building, Wentworth Woodhouse, we see today. -

Councillor First Name Division Scheme Details Total Spent Status

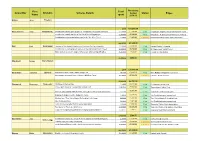

First Total Remaining Councillor Division Scheme Details budget Status Payee Name spent 2009-10 Bailey John Finedon £0.00 £10,000.00 Beardsworth Sally Kingsthorpe Contribution towards play equipment - Kingsthorpe Play Builders Project £2,500.00 £7,500.00 Paid Kingsthorpe Neighbourhood Management Board Contribution towards the hire of the YMCA Bus in Kingsthorpe £1,500.00 £6,000.00 Paid Kingsthorpe Neighbourhood Management Board Contribution to design & printing costs for the 'We Were There' £100.00 £5,900.00 In progress Northamptonshire Black History Association £4,100.00 £5,900.00 Bell Paul Swanspool Opening of the Daylight Centre over Christmas for the vulnerable £1,500.00 £8,500.00 Paid Daylight Centre Fellowship Contribution to employing a p/t worker at Wellingborough Youth Project £2,800.00 £5,700.00 Paid Wellingborough Youth Project Motor skills develoment equipment for people with learning difficulties £5,250.00 £450.00 Paid Friends of Friars School £9,550.00 £450.00 Blackwell George Earls Barton £0.00 £10,000.00 Boardman Catherine Uplands New kitchen floor - West Haddon Village Hall £803.85 £9,196.15 Paid West Haddon Village Hall Committee New garage doors and locks - Lilbourne Mini Bus Garage £3,104.65 £6,091.50 In progress Lilbourne Parish Council £3,908.50 £6,091.50 Bromwich Rosemary Towcester A5 Rangers Cycling Club £759.00 £9,241.00 Paid A5 Rangers Cycling Club Cricket pitch cover for Towcestrians Cricket Club £1,845.00 £7,396.00 Paid Towcestrians Cricket Club £6,861.00 Home & away playing shirts for Towcester Ladies Hockey -

Neighbourhood Environmental Services

Cabinet Member Report for Regeneration, Enterprise and Planning Northampton Borough Council 2nd March 2015 Regeneration The economic and physical regeneration of Northampton was one of this Administration’s key priorities on taking control of the Borough Council in 2011. All of the projects below have benefitted the residents of Northampton by generating inward investment, improving skills, modernising transportation links, creating more incentives for people to visit and generally supporting business in our town to create jobs and a thriving local economy. Project Angel Plans were approved in May 2014 to transform derelict land in the heart of Northampton into a new iconic headquarters and office building for Northamptonshire County Council, saving tax payers millions of pounds and generating a massive cash injection to the town centre economy. The building is due to open in autumn 2016 and bring 2,000 workers back into the town centre and the sod cutting ceremony took place on 10th February. University of Northampton In 2012, the University of Northampton announced plans to build a new single-site campus in the Enterprise Zone to capitalise on the links with research and innovation in technology. Plans were approved in July 2014 and the new campus is due to open in 2018. Work commenced in December 2013 on a new Innovation Centre opposite the Railway Station which will provide premises for up to 60 small and start-up businesses and enhance the Enterprise Zone offer for the town. The Innovation Centre will open this spring. In March 2014 the new Halls of Residence opened at St John’s bringing 464 students to live in the town centre and making Northampton a true University town Sixfields The Administration worked with Northampton Town Football Club to facilitate the redevelopment of Sixfields Stadium and the surrounding area with a £12 million loan deal which was announced in July 2013.