Voices from the Garden the Twelve Bronze Statues and Their Stories

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Origins of a Free Press in Prerevolutionary Virginia: Creating

Dedication To my late father, Curtis Gordon Mellen, who taught me that who we are is not decided by the advantages or tragedies that are thrown our way, but rather by how we deal with them. Table of Contents Foreword by David Waldstreicher....................................................................................i Acknowledgements .........................................................................................................iii Chapter 1 Prologue: Culture of Deference ...................................................................................1 Chapter 2 Print Culture in the Early Chesapeake Region...........................................................13 A Limited Print Culture.........................................................................................14 Print Culture Broadens ...........................................................................................28 Chapter 3 Chesapeake Newspapers and Expanding Civic Discourse, 1728-1764.......................57 Early Newspaper Form...........................................................................................58 Changes: Discourse Increases and Broadens ..............................................................76 Chapter 4 The Colonial Chesapeake Almanac: Revolutionary “Agent of Change” ...................97 The “Almanacks”.....................................................................................................99 Chapter 5 Women, Print, and Discourse .................................................................................133 -

The Smithfield Review, Volume 20, 2016

In this issue — On 2 January 1869, Olin and Preston Institute officially became Preston and Olin Institute when Judge Robert M. Hudson of the 14th Circuit Court issued a charter Includes Ten Year Index for the school, designating the new name and giving it “collegiate powers.” — page 1 The On June 12, 1919, the VPI Board of Visitors unanimously elected Julian A. Burruss to succeed Joseph D. Eggleston as president of the Blacksburg, Virginia Smithfield Review institution. As Burruss began his tenure, veterans were returning from World War I, and America had begun to move toward a post-war world. Federal programs Studies in the history of the region west of the Blue Ridge for veterans gained wide support. The Nineteenth Amendment, giving women Volume 20, 2016 suffrage, gained ratification. — page 27 A Note from the Editors ........................................................................v According to Virginia Tech historian Duncan Lyle Kinnear, “he [Conrad] seemed Olin and Preston Institute and Preston and Olin Institute: The Early to have entered upon his task with great enthusiasm. Possessed as he was with a flair Years of Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University: Part II for writing and a ‘tongue for speaking,’ this ex-confederate secret agent brought Clara B. Cox ..................................................................................1 a new dimension of excitement to the school and to the town of Blacksburg.” — page 47 Change Amidst Tradition: The First Two Years of the Burruss Administration at VPI “The Indian Road as agreed to at Lancaster, June the 30th, 1744. The present Faith Skiles .......................................................................................27 Waggon Road from Cohongoronto above Sherrando River, through the Counties of Frederick and Augusta . -

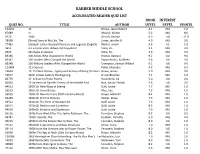

Barber Middle School Accelerated Reader Quiz List Book Interest Quiz No

BARBER MIDDLE SCHOOL ACCELERATED READER QUIZ LIST BOOK INTEREST QUIZ NO. TITLE AUTHOR LEVEL LEVEL POINTS 124151 13 Brown, Jason Robert 4.1 MG 5.0 87689 47 Mosley, Walter 5.3 MG 8.0 5976 1984 Orwell, George 8.9 UG 17.0 78958 (Short) Story of My Life, The Jones, Jennifer B. 4.0 MG 3.0 77482 ¡Béisbol! Latino Baseball Pioneers and Legends (English) Winter, Jonah 5.6 LG 1.0 9611 ¡Lo encontramos debajo del fregadero! Stine, R.L. 3.1 MG 2.0 9625 ¡No bajes al sótano! Stine, R.L. 3.9 MG 3.0 69346 100 Artists Who Changed the World Krystal, Barbara 9.7 UG 9.0 69347 100 Leaders Who Changed the World Paparchontis, Kathleen 9.8 UG 9.0 69348 100 Military Leaders Who Changed the World Crompton, Samuel Willard 9.1 UG 9.0 122464 121 Express Polak, Monique 4.2 MG 2.0 74604 13: Thirteen Stories...Agony and Ecstasy of Being Thirteen Howe, James 5.0 MG 9.0 53617 1621: A New Look at Thanksgiving Grace/Bruchac 7.1 MG 1.0 66779 17: A Novel in Prose Poems Rosenberg, Liz 5.0 UG 4.0 80002 19 Varieties of Gazelle: Poems of the Middle East Nye, Naomi Shihab 5.8 UG 2.0 44511 1900-10: New Ways of Seeing Gaff, Jackie 7.7 MG 1.0 53513 1900-20: Linen & Lace Mee, Sue 7.3 MG 1.0 56505 1900-20: New Horizons (20th Century-Music) Hayes, Malcolm 8.4 MG 1.0 62439 1900-20: Print to Pictures Parker, Steve 7.3 MG 1.0 44512 1910-20: The Birth of Abstract Art Gaff, Jackie 7.6 MG 1.0 44513 1920-40: Realism and Surrealism Gaff, Jackie 8.3 MG 1.0 44514 1940-60: Emotion and Expression Gaff, Jackie 7.9 MG 1.0 36116 1940s from World War II to Jackie Robinson, The Feinstein, Stephen 8.3 -

One Hundred Fifteenth Congress of the United States of America

H. R. 984 One Hundred Fifteenth Congress of the United States of America AT THE SECOND SESSION Begun and held at the City of Washington on Wednesday, the third day of January, two thousand and eighteen An Act To extend Federal recognition to the Chickahominy Indian Tribe, the Chickahominy Indian Tribe—Eastern Division, the Upper Mattaponi Tribe, the Rappahannock Tribe, Inc., the Monacan Indian Nation, and the Nansemond Indian Tribe. Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, SECTION 1. SHORT TITLE; TABLE OF CONTENTS. (a) SHORT TITLE.—This Act may be cited as the ‘‘Thomasina E. Jordan Indian Tribes of Virginia Federal Recognition Act of 2017’’. (b) TABLE OF CONTENTS.—The table of contents of this Act is as follows: Sec. 1. Short title; table of contents. Sec. 2. Indian Child Welfare Act of 1978. TITLE I—CHICKAHOMINY INDIAN TRIBE Sec. 101. Findings. Sec. 102. Definitions. Sec. 103. Federal recognition. Sec. 104. Membership; governing documents. Sec. 105. Governing body. Sec. 106. Reservation of the Tribe. Sec. 107. Hunting, fishing, trapping, gathering, and water rights. TITLE II—CHICKAHOMINY INDIAN TRIBE—EASTERN DIVISION Sec. 201. Findings. Sec. 202. Definitions. Sec. 203. Federal recognition. Sec. 204. Membership; governing documents. Sec. 205. Governing body. Sec. 206. Reservation of the Tribe. Sec. 207. Hunting, fishing, trapping, gathering, and water rights. TITLE III—UPPER MATTAPONI TRIBE Sec. 301. Findings. Sec. 302. Definitions. Sec. 303. Federal recognition. Sec. 304. Membership; governing documents. Sec. 305. Governing body. Sec. 306. Reservation of the Tribe. Sec. 307. Hunting, fishing, trapping, gathering, and water rights. -

Indian Women and the Law, 1830 to 1934 Bethany Berger University of Connecticut School of Law

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Faculty Articles and Papers School of Law 1997 After Pocahontas: Indian Women and the Law, 1830 to 1934 Bethany Berger University of Connecticut School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/law_papers Part of the Indian and Aboriginal Law Commons Recommended Citation Berger, Bethany, "After Pocahontas: Indian Women and the Law, 1830 to 1934" (1997). Faculty Articles and Papers. 113. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/law_papers/113 +(,121/,1( Citation: 21 Am. Indian L. Rev. 1 1997 Content downloaded/printed from HeinOnline (http://heinonline.org) Tue Aug 16 12:47:23 2016 -- Your use of this HeinOnline PDF indicates your acceptance of HeinOnline's Terms and Conditions of the license agreement available at http://heinonline.org/HOL/License -- The search text of this PDF is generated from uncorrected OCR text. -- To obtain permission to use this article beyond the scope of your HeinOnline license, please use: https://www.copyright.com/ccc/basicSearch.do? &operation=go&searchType=0 &lastSearch=simple&all=on&titleOrStdNo=0094-002X AFTER POCAHONTAS: INDIAN WOMEN AND THE LAW, 1830 TO 1934 Bethany Ruth Berger* Table of Contents I. Introduction . ..................................... 2 II. The Nineteenth Century and Indian Women: Federal Indian Policy and the Cult of True Womanhood ....................... 6 I. Federal and State Governments and Indian Women: As Them- selves, as Mothers, and as Wives ...................... 12 A. The Beginning: Ladiga's Heirs and Indian Women in Their Own Right ...................................... 12 B. Indian Women as Wives and Mothers: Intermarriage and Beyond . ........................................ 22 1. A Not So Brief Note on Intermarriage ................. 23 2. -

Virginia Historical Society the CENTER for VIRGINIA HISTORY

Virginia Historical Society THE CENTER FOR VIRGINIA HISTORY ANNUAL REPORT FOR 2004 ANNUAL MEETING, 23 APRIL 2005 Annual Report for 2004 Introduction Charles F. Bryan, Jr. President and Chief Executive Officer he most notable public event of 2004 for the Virginia Historical Society was undoubtedly the groundbreaking ceremony on the first of TJuly for our building expansion. On that festive afternoon, we ushered in the latest chapter of growth and development for the VHS. By turning over a few shovelsful of earth, we began a construction project that will add much-needed programming, exhibition, and storage space to our Richmond headquarters. It was a grand occasion and a delight to see such a large crowd of friends and members come out to participate. The representative individuals who donned hard hats and wielded silver shovels for the formal ritual of begin- ning construction stood in for so many others who made the event possible. Indeed, if the groundbreaking was the most important public event of the year, it represented the culmination of a vast investment behind the scenes in forward thinking, planning, and financial commitment by members, staff, trustees, and friends. That effort will bear fruit in 2006 in a magnifi- cent new facility. To make it all happen, we directed much of our energy in 2004 to the 175th Anniversary Campaign–Home for History in order to reach the ambitious goal of $55 million. That effort is on track—and for that we can be grateful—but much work remains to be done. Moreover, we also need to continue to devote resources and talent to sustain the ongoing programs and activities of the VHS. -

Secretary Lisa Hicks-Thomas Em Bowles Locker Alsop Lissy Bryan Senator Mary Margaret Whipple Jacqueline Hedblom Susan Schaar

Women of Virginia Commemorative Commission Executive Board November 8, 2013 Minutes Members in Attendance: Secretary Lisa Hicks-Thomas Em Bowles Locker Alsop Lissy Bryan Senator Mary Margaret Whipple Jacqueline Hedblom Susan Schaar Others in attendance: Dr. Sandra Treadway Alice Lynch Mary Blanton Easterly The meeting began and greetings were extended to visitors. Secretary Hicks-Thomas then led a discussion regarding an e-mail sent to the Executive Board from Commission Member Mary Abelsmith. Regarding the concerns of the e-mail, the Executive Board resolved that they had already received a concrete timeline on the project as submitted by the artist, that the current funds raised are being held by the Capitol Foundation and that Alice Lynch will talk more about current fundraising efforts at the next meeting of the Full Commission. Members of the Executive Board then held a brief discussion about potential names for the Monument that had not previously been submitted. Susan Schaar brought up the potential to have a female athlete as a figure on the Monument. Ms. Schaar also discussed the major role women have played in the conservation of Virginia and suggested the name Elisabeth Scott Bocock. Em Bowles Alsop also suggested the Gibson girl and Mary Wells Ashworth. Alice Lynch questioned if Lottie Moon should be reconsidered. A suggestion from the audience of Pat Perkinson, the first female Secretary of the Commonwealth of Virginia, was made. An audience member also suggested Henrietta Lacks. The Board then discussed the information provided to them by Dr. Treadway on the list of names they had previously chosen. -

Indian Raids and Massacres of Southwest Virginia

Indian Raids and Massacres of Southwest Virginia LAS VEGAS FAMILY HISTORY CENTER by Luther F. Addington and Emory L. Hamilton Published by Cecil L. Durham Kingsport, Tennessee FHL TITLE # 488344 Chapters I through XV are an exact reprint of "Indian Stories of Virginia's Last Frontier" by Luther F. Addington and originally published by The Historical Society of Southwest Virginia. Chapter XVI "Indian Tragedies Against the Walker Family" is by Emory L. Hamilton. Printed in the United States of America by Kingsport Press Kingsport, Tennessee TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE I. INDIANS CAPTURE MARY INGLES 1 II. MURDER OF JAMES BOONE, 27 OCTOBER 10, 1773 III. MASSACRE OF THE HENRY FAMILY 35 IV. THE INDIAN MISSIONARY 38 V. CAPTURE OF JANE WHITAKER AND POLLY ALLEY 42 VI. ATTACK ON THE EVANS FAMILY, 1779 48 VII. ATTACK ON THOMAS INGLES' FAMILY 54 VIII. INDIANS AND THE MOORE FAMILY 59 IX. THE HARMANS' BATTLE 77 X. A FIGHT FOR LIFE 84 XI. CHIEF BENGE CARRIES AWAY MRS. SCOTT 88 XII. THE CAPTIVITY OF JENNY WILEY 97 XIII. MRS. ANDREW DAVIDSON AND CHILDREN CAPTURED 114 XIV. DAVID MUSICK TRAGEDY 119 XV. CHIEF BENGE'S LAST RAID 123 XVI. INDIAN TRAGEDIES AGAINST THE WALKER FAMILY NOTE: The interesting story of Caty Sage, who was stolen from her parents in Grayson County, 1792, by a vengeful white man and later grew to womanhood among the Wyandotts in the West, is well told by Mrs. Bonnie Ball in her book, Red Trails and White, Haysi, Virginia. 1 I CAPTIVITY OF MARY DRAPER INGLES Of all the young women taken into captivity by the Indians from Virginia's western frontier none suffered more anguish, nor bore her hardships more heroically, nor behaved with more thoughtfulness to ward her captors than did Mary Draper Ingles. -

Indian Warfare, Household Competency, and the Settlement of the Western Virginia Frontier, 1749 to 1794

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2007 Indian warfare, household competency, and the settlement of the western Virginia frontier, 1749 to 1794 John M. Boback West Virginia University Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Boback, John M., "Indian warfare, household competency, and the settlement of the western Virginia frontier, 1749 to 1794" (2007). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 2566. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/2566 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Indian Warfare, Household Competency, and the Settlement of the Western Virginia Frontier, 1749 to 1794 John M. Boback Dissertation submitted to the College of Arts and Sciences at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor -

Virginian Writers Fugitive Verse

VIRGIN IAN WRITERS OF FUGITIVE VERSE VIRGINIAN WRITERS FUGITIVE VERSE we with ARMISTEAD C. GORDON, JR., M. A., PH. D, Assistant Proiesso-r of English Literature. University of Virginia I“ .‘ '. , - IV ' . \ ,- w \ . e. < ~\ ,' ’/I , . xx \ ‘1 ‘ 5:" /« .t {my | ; NC“ ‘.- ‘ '\ ’ 1 I Nor, \‘ /" . -. \\ ' ~. I -. Gil-T 'J 1’: II. D' VI. Doctor: .. _ ‘i 8 » $9793 Copyrighted 1923 by JAMES '1‘. WHITE & C0. :To MY FATHER ARMISTEAD CHURCHILL GORDON, A VIRGINIAN WRITER OF FUGITIVE VERSE. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS. The thanks of the author are due to the following publishers, editors, and individuals for their kind permission to reprint the following selections for which they hold copyright: To Dodd, Mead and Company for “Hold Me Not False” by Katherine Pearson Woods. To The Neale Publishing Company for “1861-1865” by W. Cabell Bruce. To The Times-Dispatch Publishing Company for “The Land of Heart‘s Desire” by Thomas Lomax Hunter. To The Curtis Publishing Company for “The Lane” by Thomas Lomax Hunter (published in The Saturday Eve- ning Post, and copyrighted, 1923, by the Curtis Publishing 00.). To the Johnson Publishing Company for “Desolate” by Fanny Murdaugh Downing (cited from F. V. N. Painter’s Poets of Virginia). To Harper & Brothers for “A Mood” and “A Reed Call” by Charles Washington Coleman. To The Independent for “Life’s Silent Third”: by Charles Washington Coleman. To the Boston Evening Transcript for “Sister Mary Veronica” by Nancy Byrd Turner. To The Century for “Leaves from the Anthology” by Lewis Parke Chamberlayne and “Over the Sea Lies Spain” by Charles Washington Coleman. To Henry Holt and Company for “Mary‘s Dream” by John Lowe and “To Pocahontas” by John Rolfe. -

The Magazine of the Broadside WINTER 2012

the magazine of the broadSIDE WINTER 2012 LOST& FOUND page 2 FEBRUARY 27–AUGUST 25, 2012 broadSIDE THE INSIDE STORY the magazine of the Joyous Homecoming LIBRARY OF VIRGINIA WINTER 2012 Eighteenth-century Stafford County records librarian of virginia discovered in New Jersey are returned to Virginia Sandra G. Treadway arly this year the Library will open an exhibition entitled Lost library board chair Eand Found. The exhibition features items from the past that Clifton A. Woodrum III have disappeared from the historical record as well as documents and artifacts, missing and presumed gone forever, that have editorial board resurfaced after many years. Suddenly, while the curators were Janice M. Hathcock Ann E. Henderson making their final choices about exhibition items from our Gregg D. Kimball collections, the Library was surprised to receive word of a very Mary Beth McIntire special “find” that has now made its way back home to Virginia. During the winter of 1862–1863, more than 100,000 Union editor soldiers with the Army of the Potomac tramped through and Ann E. Henderson camped in Stafford County, Virginia. By early in December 1862, the New York Times reported that military activity had left the copy editor Emily J. Salmon town of Stafford Court House “a scene of utter ruin.” One casualty of the Union occupation was the “house of records” located graphic designer behind the courthouse. Here, the Times recounted, “were deposited all the important Amy C. Winegardner deeds and papers pertaining to this section for a generation past.” Documents “were found lying about the floor to the depth of fifteen inches or more around the door-steps and in photography the door-yard.” Anyone who has ever tried to research Stafford County’s early history can Pierre Courtois attest to the accuracy of the newspaper’s prediction that “it is impossible to estimate the inconvenience and losses which will be incurred by this wholesale destruction.” contributors Barbara C. -

Robert Cowley: Living Free During Slavery in Eighteenth-Century Richmond, Virginia

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2020 Robert Cowley: Living Free During Slavery in Eighteenth-Century Richmond, Virginia Ana F. Edwards Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, Other American Studies Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/6362 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Robert Cowley: Living Free During Slavery in Eighteenth-Century Richmond, Virginia A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts from the Department of History at Virginia Commonwealth University. by Ana Frances Edwards Wilayto Bachelor of Arts, California State Polytechnic University at Pomona, 1983 Director of Record: Ryan K. Smith, Ph. D., Professor, Department of History, Virginia Commonwealth University Adviser: Nicole Myers Turner, Ph. D., Professor, Department of Religious Studies, Yale University Outside Reader: Michael L. Blakey, Ph. D., Professor, Department of Anthropology, College of William & Mary Virginia Commonwealth University Richmond, Virginia June 2020 © Ana Frances Edwards Wilayto 2020 All Rights Reserved 2 of 115 For Grandma Thelma and Grandpa Melvin, Grandma Mildred and Grandpa Paul. For Mom and Dad, Allma and Margit. For Walker, Taimir and Phil. Acknowledgements I am grateful to the professors--John Kneebone, Carolyn Eastman, John Herman, Brian Daugherty, Bernard Moitt, Ryan Smith, and Sarah Meacham--who each taught me something specific about history, historiography, academia and teaching.