The Lyons Housing Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Energy Challenge Energy Review Report 2006 Department of Trade and Industry

The Energy Challenge ENERGY REVIEW A Report JULY 2006 The Energy Challenge Energy Review Report 2006 Department of Trade and Industry Presented to Parliament by the Secretary of State for Trade and Industry By Command of Her Majesty July 2006 Cm 6887 £22.00 © Crown copyright 2006 The text in this document (excluding the Royal Arms and departmental logos) may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium providing that it is reproduced accurately and not used in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as Crown copyright and the title of the document specified. Any enquiries relating to the copyright in this document should be addressed to The Licensing Division, HMSO, St Clements House, 2-16 Colegate, Norwich, NR3 1BQ. Fax: 01603 723000 or e-mail: [email protected] Contents Foreword by the Rt Hon. Tony Blair MP 4 Preface by the Rt Hon. Alistair Darling MP 8 Introduction 10 Executive Summary 12 Chapter 1: Valuing Carbon 27 Chapter 2: Saving Energy 36 Chapter 3: Distributed Energy 61 Chapter 4: Oil, Gas and Coal 77 • International Energy Security 78 • Oil and Gas 83 • Coal 84 • Energy Imports 86 Chapter 5: Electricity Generation 92 • Renewables 98 • Cleaner Coal and Carbon Capture and Storage 107 • Nuclear 113 Chapter 6: Transport 126 Chapter 7: Planning for Large-scale Energy Infrastructure 134 Chapter 8: Meeting Our Goals 149 Chapter 9: Implementation 156 Annexes 161 3 Foreword by the Rt Hon. Tony Blair MP A clean, secure and sufficient supply of energy is simply essential for the future of our country. -

THE 422 Mps WHO BACKED the MOTION Conservative 1. Bim

THE 422 MPs WHO BACKED THE MOTION Conservative 1. Bim Afolami 2. Peter Aldous 3. Edward Argar 4. Victoria Atkins 5. Harriett Baldwin 6. Steve Barclay 7. Henry Bellingham 8. Guto Bebb 9. Richard Benyon 10. Paul Beresford 11. Peter Bottomley 12. Andrew Bowie 13. Karen Bradley 14. Steve Brine 15. James Brokenshire 16. Robert Buckland 17. Alex Burghart 18. Alistair Burt 19. Alun Cairns 20. James Cartlidge 21. Alex Chalk 22. Jo Churchill 23. Greg Clark 24. Colin Clark 25. Ken Clarke 26. James Cleverly 27. Thérèse Coffey 28. Alberto Costa 29. Glyn Davies 30. Jonathan Djanogly 31. Leo Docherty 32. Oliver Dowden 33. David Duguid 34. Alan Duncan 35. Philip Dunne 36. Michael Ellis 37. Tobias Ellwood 38. Mark Field 39. Vicky Ford 40. Kevin Foster 41. Lucy Frazer 42. George Freeman 43. Mike Freer 44. Mark Garnier 45. David Gauke 46. Nick Gibb 47. John Glen 48. Robert Goodwill 49. Michael Gove 50. Luke Graham 51. Richard Graham 52. Bill Grant 53. Helen Grant 54. Damian Green 55. Justine Greening 56. Dominic Grieve 57. Sam Gyimah 58. Kirstene Hair 59. Luke Hall 60. Philip Hammond 61. Stephen Hammond 62. Matt Hancock 63. Richard Harrington 64. Simon Hart 65. Oliver Heald 66. Peter Heaton-Jones 67. Damian Hinds 68. Simon Hoare 69. George Hollingbery 70. Kevin Hollinrake 71. Nigel Huddleston 72. Jeremy Hunt 73. Nick Hurd 74. Alister Jack (Teller) 75. Margot James 76. Sajid Javid 77. Robert Jenrick 78. Jo Johnson 79. Andrew Jones 80. Gillian Keegan 81. Seema Kennedy 82. Stephen Kerr 83. Mark Lancaster 84. -

Going for Gold – the South Cambridgeshire Story

Going for gold The South Cambridgeshire story Written by Kevin Wilkins March 2019 Going for gold Foreword Local government is the backbone of our party, and from Cornwall to Eastleigh, Eastbourne to South Lakeland, with directly elected Mayors in Bedford and Watford, Liberal Democrats are making a real difference in councils across the country. So I was delighted to be asked to write this foreword for one of the latest to join that group of Liberal Democrat Jo Swinson MP CBE councils, South Cambridgeshire. Deputy Leader Liberal Democrats Every council is different, and their story is individual to them. It’s important that we learn what works and what doesn’t, and always be willing to tell our story so others can learn. Good practice booklets like this one produced by South Cambridgeshire Liberal Democrats and the Liberal Democrat Group at the Local Government Association are tremendously useful. 2 This guide joins a long list of publications that they have produced promoting the successes of our local government base in places as varied as Liverpool, Watford and, more recently, Bedford. Encouraging more women to stand for public office is a campaign I hold close to my heart. It is wonderful to see a group of 30 Liberal Democrat councillors led by Councillor Bridget Smith, a worthy addition to a growing number of Liberal Democrat women group and council leaders such as Councillor Liz Green (Kingston Upon Thames), Councillor Sara Bedford (Three Rivers) Councillor Val Keitch (South Somerset), Councillor Ruth Dombey (Sutton), and Councillor Aileen Morton (Argyll and Bute) South Cambridgeshire Liberal Democrats are leading the way in embedding nature capital into all of their operations, policies and partnerships, focusing on meeting the housing needs of all their residents, and in dramatically raising the bar for local government involvement in regional economic development. -

Register of All-Party Parliamentary Groups

Register of All-Party Parliamentary Groups Published 29 August 2018 REGISTER OF ALL-PARTY PARLIAMENTARY GROUPS Contents INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................................................... 3 The Nature of All-Party Parliamentary Groups ...................................................................................................... 3 Information and advice about All-Party Parliamentary Groups ............................................................................ 3 COUNTRY GROUPS .................................................................................................................................................... 4 SUBJECT GROUPS ................................................................................................................................................... 187 2 | P a g e REGISTER OF ALL-PARTY PARLIAMENTARY GROUPS INTRODUCTION The Nature of All-Party Parliamentary Groups An All-Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) consists of Members of both Houses who join together to pursue a particular topic or interest. In order to use the title All-Party Parliamentary Group, a Group must be open to all Members of both Houses, regardless of party affiliation, and must satisfy the rules agreed by the House for All-Party Parliamentary Groups. The Register of All-Party Parliamentary Groups, which is maintained by the Parliamentary Commissioner for Standards, is a definitive list of such groups. It contains the financial -

THE PLACE of SOCIAL HOUSING in INTEGRATED URBAN POLICIES Current Perspectives Edited by Darinka Czischke

URBAN REGENERATION IN EUROPE: THE PLACE OF SOCIAL HOUSING IN INTEGRATED URBAN POLICIES Current perspectives Edited by Darinka Czischke 1 Urban regeneration in Europe: The place of social housing in integrated urban policies Current perspectives Edited by Darinka Czischke May 2009 Published by the CECODHAS European Social Housing Observatory Sponsored by BSHF (Building and Social Housing Foundation) 3 This publication was produced by the CECODHAS European Social Housing Observatory, Brussels (Belgium). It was sponsored by the Building and Social Housing Foundation (BSHF) (United Kingdom). ISBN 978–92–95063–08–2 Edited by Darinka Czischke Design by Maciej Szkopanski, [email protected] Printed by Production Sud, Brussels Photographs by Darinka Czischke. Brussels, May 2009. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Foreword David Orr 07 Introduction Darinka Czischke 09 Perspectives Achieving Balanced Communities: Challenges and Responses Nicholas Falk 12 Policy measures to tackle urban regeneration in early post–war neighbourhoods: A refl ection from the Netherlands Karien Dekker 25 On the Governance of Social Housing John Flint 35 From “bricks-and-mortar” investors to community anchors: Social housing governance and the role of Dutch housing associations in urban regeneration Gerard van Bortel 45 Conclusions Sustainable urban regeneration in Europe: Rethinking the place of social housing in integrated policies Darinka Czischke 59 About the authors 71 5 PUBLISHER CECODHAS European Social Housing Observatory www.cecodhas.org/observatory The Observatory is the research branch of CECODHAS. Its main aim is to identify and analyse key trends and research needs in the fi eld of housing and social housing at European level. Its role is to support policy work for the delivery of social housing by providing strategic and evidence-based analysis in the fi eld. -

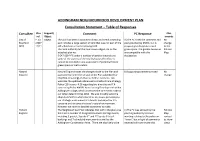

Consultation Statement – Table of Responses Consultee Plan Support/ Comment PC Response Plan Ref

ADDINGHAM NEIGHBOURHOOD DEVELOPMENT PLAN Consultation Statement – Table of Responses Consultee Plan Support/ Comment PC Response Plan ref. Object amends City of P. 53 Object The plan has been inaccurately drawn and needs amending A) The PC notes the comment and No Bradford ANDP as it includes a large section of land that was not part of the plan provided by BMDC, but is change MDC 11/11 old school site or former playing field. proposing to designate a local to the The local authority let the land shown edged red on the green space. The garden tenancies Policies attached plan no. are compatible with this Map. S-047-009-PFG under a number of garden tenancies to designation. some of the owners of the nearby houses therefore it cannot be included in any assessment of potential future green space in that location. Natural Natural England notes the changes made to the Plan and B) Supporting comments noted No England assessments [since the version of the Plan submitted for change SEA/HRA screening] and has no further concerns. We welcome the updated references to Bradford Core Strategy Policy CS8 in para. 4.20 regarding bio-diversity and 7.4 concerning Policy ANDP1 New Housing Development within Addingham village, which addresses the comments made in our letter dated 15 May 2018. We also broadly welcome chap.4 of the Plan which identifies key issues pertaining to our strategic environmental interests and objective 3 to conserve and enhance the area’s natural environment. However we have no detailed comments to make. Historic The Neighbourhood Plan indicates that within the plan area C) The PC was advised by the Policies England there are a number of designated cultural heritage assets, planning authority to revise Map including 3 grade I, 3 grade II* and 115 grade II listed wording relating to the policy on revised buildings and 7 scheduled monuments as well as the “views”, but in light of comments to show Addingham Conservation Area. -

Matthew Gregory Chief Executive Firstgroup Plc 395

Matthew Gregory House of Commons, Chief Executive London, FirstGroup plc SW1A0AA 395 King Street Aberdeen AB24 5RP 15 October 2019 Dear Mr Gregory As West Yorkshire MPs, we are writing as FirstGroup are intending to sell First Bus and to request that the West Yorkshire division of the company is sold as a separate entity. This sale represents a singular opportunity to transform bus operations in our area and we believe it is in the best interests of both FirstGroup and our constituents for First Bus West Yorkshire to be taken into ownership by the West Yorkshire Combined Authority (WYCA). To this end, we believe that WYCA should have the first option to purchase this division. In West Yorkshire, the bus as a mode of travel is particularly relied upon by many of our constituents to get to work, appointments and to partake in leisure activities. We have a long-shared aim of increasing the usage of buses locally as a more efficient and environmentally friendly alternative to the private car. We believe that interest is best served by allowing for passengers to have a stake in their own service through the local combined authority. There is wide spread public support for this model as a viable direction for the service and your facilitation of this process through the segmentation of the sale can only reflect well on FirstGroup. We, as representatives of the people of West Yorkshire request a meeting about the future of First Bus West Yorkshire and consideration of its sale to West Yorkshire Combined Authority. Yours sincerely, Alex Sobel MP Tracey Brabin MP Imran Hussain MP Judith Cummins MP Naz Shah MP Thelma Walker MP Paula Sherriff MP Holly Lynch MP Jon Trickett MP Barry Sheerman MP John Grogan MP Hilary Benn MP Richard Burgon MP Fabian Hamilton MP Rachel Reeves MP Yvette Cooper MP Mary Creagh MP Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org). -

The Land Border Between Northern Ireland and Ireland

House of Commons Northern Ireland Affairs Committee The land border between Northern Ireland and Ireland Second Report of Session 2017–19 HC 329 House of Commons Northern Ireland Affairs Committee The land border between Northern Ireland and Ireland Second Report of Session 2017–19 Report, together with formal minutes relating to the report Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 13 March 2018 HC 329 Published on 16 March 2018 by authority of the House of Commons Northern Ireland Affairs Committee The Northern Ireland Affairs Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration, and policy of the Northern Ireland Office (but excluding individual cases and advice given by the Crown Solicitor); and other matters within the responsibilities of the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland (but excluding the expenditure, administration and policy of the Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions, Northern Ireland and the drafting of legislation by the Office of the Legislative Counsel). Current membership Dr Andrew Murrison MP (Conservative, South West Wiltshire) (Chair) Mr Gregory Campbell MP (Democratic Unionist Party, East Londonderry) Mr Robert Goodwill MP (Conservative, Scarborough and Whitby ) John Grogan MP (Labour, Keighley) Mr Stephen Hepburn MP (Labour, Jarrow) Lady Hermon MP (Independent, North Down) Kate Hoey MP (Labour, Vauxhall) Jack Lopresti MP (Conservative, Filton and Bradley Stoke) Conor McGinn MP (Labour, St Helens North) Nigel Mills MP (Conservative, Amber Valley) Ian Paisley MP (Democratic Unionist Party, North Antrim) Jim Shannon MP (Democratic Unionist Party, Strangford) Bob Stewart MP (Conservative, Beckenham) Powers The Committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 152. -

Northstowe New Town, Cambridgeshire

Landscape Masterplanning and Design | Public Realm Location UK Northstowe New Town, Cambridgeshire Client Landscape Strategy and Design Codes Homes England Northstowe is designed as a 21st century town in Cambridgeshire with up to Budget 10,000 residential homes that will take shape over a period of 15-20 years. It Confidential aims to achieve the highest quality of community living, conserving precious Period resources and contributing to the local identity of the area and supporting a 2015 - 2016 vibrant community. Founded on contemporary place-making principles, it will reference the spatial character of fen-edge market towns, making provision for Services more sustainable patterns of living. As part of a multi-discliplinary team and Masterplanning Landscape and Public Realm Design within the context of the development principles of the Northstowe Action Plan, Consultation CBA prepared the landscape and public realm strategy and design codes for the Northstowe Phase 2 Development. The Codes evolved from a collaborative Website process involving South Cambridgeshire District Council, Cambridge County www.cbastudios.com Council and the local community. The landscape and open space strategy for Northstowe Phase 2 is the provision of a robust landscape framework that contributes a rich variety of landscapes, open spaces and green routes proposed to meet the needs of the new and existing local communities. The landscape strategy seeks to create multi-functional high quality landscape and open spaces that deliver on the aspiration for Northstowe to become a ‘Healthy Town’ under the NHS England Healthy Town initiative. ARUP © 0286. -

Congratulations Issue 14 17Th July 2017

SACRED HEART CATHOLIC PRIMARY , A VOLUNTARY ACADEMY Jesus said, “I chose you, and appointed you to go and bear much fruit.” Website:www.sacredheartilkley.co.uk (Company Number: 8399801) Congratulations Issue 14 17th July 2017 Dear Parents, OFFICE NEWS Congratulations to all the children who have worked so hard and successfully completed the recent national tests. The results below School Lunch Cost show the percentage achieving Age Related Expectation and above, the government has not yet released the scaled scores for Greater Please note that from Depth in Reading, Spelling, Grammar and Punctuation, and Maths. September the price of school lunches will be £2.30 per day. %ARE+ Sacred Heart Indicative National 6 Peak Challenge Y1 Phonics Check 88 Thank you to everyone KS1 Reading 84 who very generously KS 1Writing 75 sponsored Mrs Meadows’ amazing 6 Peak Challenge KS1 SPaG (optional) 84 and Year 6’s sponsored KS1 Maths 78 walk. The grand total raised for the British KS1 RWM 72 Heart Foundation and the KS2 Reading 97 71 LGI Heart Unit is £482. KS2 SGaP 97 77 Thank you. KS2 Writing 86 76 Mrs Cheetham and KS2 Writing Greater 20 Mrs Shaw Depth KS2 Maths 90 75 KS2 RWM 83 61 Best wishes Mrs Hogan (Deputy Headteacher) Hills and Adventure Trail Please support the school DIARY DATES rules at the end of the day. The children know 19th July Year 5/6 Production @ 2pm and 7pm they are not allowed on the hills or the adventure 20th July Sports Awards’ Assembly @ 2.45pm trail at the end of the 21st July Whole School Mass– Year 6 Leavers day. -

Oakervee Review

1 Contents 1. Chair’s Foreword............................................................................................3 2. Introducton....................................................................................................5 3. Executve summary......................................................................................11 4. What is HS2..................................................................................................19 5. Review of the objectves for HS2.................................................................24 . The HS2 design and route............................................................................41 7. Cost and schedule........................................................................................55 8. Contractng and HS2 specifcatons..............................................................66 9. HS2 statons..................................................................................................72 10. Capability, governance and oversight.......................................................80 11. Economic assessment of HS2....................................................................93 12. Alternatve Optons.................................................................................107 Annex A: Glossary.............................................................................................116 Annex B: Terms of Reference...........................................................................121 Annex C: Meetngs and Evidence.....................................................................125 -

Northstowe Phase 2 Planning Application

NORTHSTOWE PHASE 2 PLANNING APPLICATION Stakeholder and Community Engagement Report August 2014 Homes & Communities Agency Northstowe Phase 2 Stakeholder and Community Engagement Report Contents Page 1 Introduction 1 2 Pre-Application Consultation 2 3 Methods of Pre-application Consultation 3 3.1 Council and Technical Consultee Engagement 3 3.2 Member Engagement 6 3.3 Rampton Drift Consultation 12 3.4 Public Consultation 14 4 How the comments received have been taken into account 28 4.1 Scope of applications 28 4.2 Layout and design 28 5 Conclusion 31 Appendices Appendix A Consultation Strategy A1 Consultation Strategy Appendix B Quality Panel Reponse B1 Letter Received from Cambridgeshire Quality Panel Appendix C Rampton Drift Consultation C1 Letters C2 Workshop Material 8 February 2014 C3 Workshop Materials 8 April 2014 C4 Analysis of Response Appendic D Public Consultation D1 Staffed Public Exhibition Boards D2 Unstaffed Public Exhibition Boards D3 Consultation Material D3.1 Information Leaflet and Comment Form D4 Publicity D4.1 Leaflet D4.2 Website D4.3 Press Release D4.4 Social Media D4.5 Poster D5 Analysis of Response Page 1 | Issue | August 2014 Homes & Communities Agency Northstowe Phase 2 Stakeholder and Community Engagement Report Page 2 | Issue | August 2014 Homes & Communities Agency Northstowe Phase 2 Stakeholder and Community Engagement Report 1 Introduction This Stakeholder and Community Engagement Report has been prepared by Arup on behalf of the Homes and Communities Agency, “the applicant”, in support of a planning application for development of Phase 2 of Northstowe. Further information about the proposals is provided in the Planning Statement, submitted in support of the applications.