Engineered Telomere Degradation Models Dyskeratosis Congenita

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inherited Bone Marrow Failure Syndrome (IBMFS) Testing

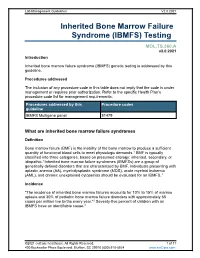

Lab Management Guidelines V2.0.2021 Inherited Bone Marrow Failure Syndrome (IBMFS) Testing MOL.TS.360.A v2.0.2021 Introduction Inherited bone marrow failure syndrome (IBMFS) genetic testing is addressed by this guideline. Procedures addressed The inclusion of any procedure code in this table does not imply that the code is under management or requires prior authorization. Refer to the specific Health Plan's procedure code list for management requirements. Procedures addressed by this Procedure codes guideline IBMFS Multigene panel 81479 What are inherited bone marrow failure syndromes Definition Bone marrow failure (BMF) is the inability of the bone marrow to produce a sufficient quantity of functional blood cells to meet physiologic demands.1 BMF is typically classified into three categories, based on presumed etiology: inherited, secondary, or idiopathic.1 Inherited bone marrow failure syndromes (IBMFSs) are a group of genetically defined disorders that are characterized by BMF. Individuals presenting with aplastic anemia (AA), myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), acute myeloid leukemia (AML), and chronic unexplained cytopenias should be evaluated for an IBMFS.1 Incidence "The incidence of inherited bone marrow failures accounts for 10% to 15% of marrow aplasia and 30% of pediatric bone marrow failure disorders with approximately 65 cases per million live births every year."2 Seventy-five percent of children with an IBMFS have an identifiable cause.2 ©2021 eviCore healthcare. All Rights Reserved. 1 of 17 400 Buckwalter Place Boulevard, Bluffton, SC 29910 (800) 918-8924 www.eviCore.com Lab Management Guidelines V2.0.2021 Symptoms While specific features may vary by each type of IBMFS, features that are present in most IBMFSs include bone marrow failure with single or multi-lineage cytopenia. -

Open Full Page

CCR PEDIATRIC ONCOLOGY SERIES CCR Pediatric Oncology Series Recommendations for Childhood Cancer Screening and Surveillance in DNA Repair Disorders Michael F. Walsh1, Vivian Y. Chang2, Wendy K. Kohlmann3, Hamish S. Scott4, Christopher Cunniff5, Franck Bourdeaut6, Jan J. Molenaar7, Christopher C. Porter8, John T. Sandlund9, Sharon E. Plon10, Lisa L. Wang10, and Sharon A. Savage11 Abstract DNA repair syndromes are heterogeneous disorders caused by around the world to discuss and develop cancer surveillance pathogenic variants in genes encoding proteins key in DNA guidelines for children with cancer-prone disorders. Herein, replication and/or the cellular response to DNA damage. The we focus on the more common of the rare DNA repair dis- majority of these syndromes are inherited in an autosomal- orders: ataxia telangiectasia, Bloom syndrome, Fanconi ane- recessive manner, but autosomal-dominant and X-linked reces- mia, dyskeratosis congenita, Nijmegen breakage syndrome, sive disorders also exist. The clinical features of patients with DNA Rothmund–Thomson syndrome, and Xeroderma pigmento- repair syndromes are highly varied and dependent on the under- sum. Dedicated syndrome registries and a combination of lying genetic cause. Notably, all patients have elevated risks of basic science and clinical research have led to important in- syndrome-associated cancers, and many of these cancers present sights into the underlying biology of these disorders. Given the in childhood. Although it is clear that the risk of cancer is rarity of these disorders, it is recommended that centralized increased, there are limited data defining the true incidence of centers of excellence be involved directly or through consulta- cancer and almost no evidence-based approaches to cancer tion in caring for patients with heritable DNA repair syn- surveillance in patients with DNA repair disorders. -

My Beloved Neutrophil Dr Boxer 2014 Neutropenia Family Conference

The Beloved Neutrophil: Its Function in Health and Disease Stem Cell Multipotent Progenitor Myeloid Lymphoid CMP IL-3, SCF, GM-CSF CLP Committed Progenitor MEP GMP GM-CSF, IL-3, SCF EPO TPO G-CSF M-CSF IL-5 IL-3 SCF RBC Platelet Neutrophil Monocyte/ Basophil B-cells Macrophage Eosinophil T-Cells Mast cell NK cells Mature Cell Dendritic cells PRODUCTION AND KINETICS OF NEUTROPHILS CELLS % CELLS TIME Bone Marrow: Myeloblast 1 7 - 9 Mitotic Promyelocyte 4 Days Myelocyte 16 Maturation/ Metamyelocyte 22 3 – 7 Storage Band 30 Days Seg 21 Vascular: Peripheral Blood Seg 2 6 – 12 hours 3 Marginating Pool Apoptosis and ? Tissue clearance by 0 – 3 macrophages days PHAGOCYTOSIS 1. Mobilization 2. Chemotaxis 3. Recognition (Opsonization) 4. Ingestion 5. Degranulation 6. Peroxidation 7. Killing and Digestion 8. Net formation Adhesion: β 2 Integrins ▪ Heterodimer of a and b chain ▪ Tight adhesion, migration, ingestion, co- stimulation of other PMN responses LFA-1 Mac-1 (CR3) p150,95 a2b2 a CD11a CD11b CD11c CD11d b CD18 CD18 CD18 CD18 Cells All PMN, Dendritic Mac, mono, leukocytes mono/mac, PMN, T cell LGL Ligands ICAMs ICAM-1 C3bi, ICAM-3, C3bi other other Fibrinogen other GRANULOCYTE CHEMOATTRACTANTS Chemoattractants Source Activators Lipids PAF Neutrophils C5a, LPS, FMLP Endothelium LTB4 Neutrophils FMLP, C5a, LPS Chemokines (a) IL-8 Monocytes, endothelium LPS, IL-1, TNF, IL-3 other cells Gro a, b, g Monocytes, endothelium IL-1, TNF other cells NAP-2 Activated platelets Platelet activation Others FMLP Bacteria C5a Activation of complement Other Important Receptors on PMNs ñ Pattern recognition receptors – Detect microbes - Toll receptor family - Mannose receptor - bGlucan receptor – fungal cell walls ñ Cytokine receptors – enhance PMN function - G-CSF, GM-CSF - TNF Receptor ñ Opsonin receptors – trigger phagocytosis - FcgRI, II, III - Complement receptors – ñ Mac1/CR3 (CD11b/CD18) – C3bi ñ CR-1 – C3b, C4b, C3bi, C1q, Mannose binding protein From JG Hirsch, J Exp Med 116:827, 1962, with permission. -

Genetic Features of Myelodysplastic Syndrome and Aplastic Anemia in Pediatric and Young Adult Patients

Bone Marrow Failure SUPPLEMENTARY APPENDIX Genetic features of myelodysplastic syndrome and aplastic anemia in pediatric and young adult patients Siobán B. Keel, 1* Angela Scott, 2,3,4 * Marilyn Sanchez-Bonilla, 5 Phoenix A. Ho, 2,3,4 Suleyman Gulsuner, 6 Colin C. Pritchard, 7 Janis L. Abkowitz, 1 Mary-Claire King, 6 Tom Walsh, 6** and Akiko Shimamura 5** 1Department of Medicine, Division of Hematology, University of Washington, Seattle, WA; 2Clinical Research Division, Fred Hutchinson Can - cer Research Center, Seattle, WA; 3Department of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology, Seattle Children’s Hospital, WA; 4Department of Pedi - atrics, University of Washington, Seattle, WA; 5Boston Children’s Hospital, Dana Farber Cancer Institute, and Harvard Medical School, MA; 6Department of Medicine and Department of Genome Sciences, University of Washington, Seattle, WA; and 7Department of Laboratory Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA *SBK and ASc contributed equally to this work **TW and ASh are co-senior authors ©2016 Ferrata Storti Foundation. This is an open-access paper. doi:10.3324/haematol. 2016.149476 Received: May 16, 2016. Accepted: July 13, 2016. Pre-published: July 14, 2016. Correspondence: [email protected] or [email protected] Supplementary materials Supplementary methods Retrospective chart review Patient data were collected from medical records by two investigators blinded to the results of genetic testing. The following information was collected: date of birth, transplant, death, and last follow-up, -

A Curated Gene List for Reporting Results of Newborn Genomic Sequencing

© American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics ORIGINAL RESEARCH ARTICLE A curated gene list for reporting results of newborn genomic sequencing Ozge Ceyhan-Birsoy, PhD1,2,3, Kalotina Machini, PhD1,2,3, Matthew S. Lebo, PhD1,2,3, Tim W. Yu, MD3,4,5, Pankaj B. Agrawal, MD, MMSC3,4,6, Richard B. Parad, MD, MPH3,7, Ingrid A. Holm, MD, MPH3,4, Amy McGuire, PhD8, Robert C. Green, MD, MPH3,9,10, Alan H. Beggs, PhD3,4, Heidi L. Rehm, PhD1,2,3,10; for the BabySeq Project Purpose: Genomic sequencing (GS) for newborns may enable detec- of newborn GS (nGS), and used our curated list for the first 15 new- tion of conditions for which early knowledge can improve health out- borns sequenced in this project. comes. One of the major challenges hindering its broader application Results: Here, we present our curated list for 1,514 gene–disease is the time it takes to assess the clinical relevance of detected variants associations. Overall, 954 genes met our criteria for return in nGS. and the genes they impact so that disease risk is reported appropri- This reference list eliminated manual assessment for 41% of rare vari- ately. ants identified in 15 newborns. Methods: To facilitate rapid interpretation of GS results in new- Conclusion: Our list provides a resource that can assist in guiding borns, we curated a catalog of genes with putative pediatric relevance the interpretive scope of clinical GS for newborns and potentially for their validity based on the ClinGen clinical validity classification other populations. framework criteria, age of onset, penetrance, and mode of inheri- tance through systematic evaluation of published evidence. -

The Genetics and Clinical Manifestations of Telomere Biology Disorders Sharon A

REVIEW The genetics and clinical manifestations of telomere biology disorders Sharon A. Savage, MD1, and Alison A. Bertuch, MD, PhD2 3 Abstract: Telomere biology disorders are a complex set of illnesses meric sequence is lost with each round of DNA replication. defined by the presence of very short telomeres. Individuals with classic Consequently, telomeres shorten with aging. In peripheral dyskeratosis congenita have the most severe phenotype, characterized blood leukocytes, the cells most extensively studied, the rate 4 by the triad of nail dystrophy, abnormal skin pigmentation, and oral of attrition is greatest during the first year of life. Thereafter, leukoplakia. More significantly, these individuals are at very high risk telomeres shorten more gradually. When the extent of telo- of bone marrow failure, cancer, and pulmonary fibrosis. A mutation in meric DNA loss exceeds a critical threshold, a robust anti- one of six different telomere biology genes can be identified in 50–60% proliferative signal is triggered, leading to cellular senes- of these individuals. DKC1, TERC, TERT, NOP10, and NHP2 encode cence or apoptosis. Thus, telomere attrition is thought to 1 components of telomerase or a telomerase-associated factor and TINF2, contribute to aging phenotypes. 5 a telomeric protein. Progressively shorter telomeres are inherited from With the 1985 discovery of telomerase, the enzyme that ex- generation to generation in autosomal dominant dyskeratosis congenita, tends telomeric nucleotide repeats, there has been rapid progress resulting in disease anticipation. Up to 10% of individuals with apparently both in our understanding of basic telomere biology and the con- acquired aplastic anemia or idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis also have short nection of telomere biology to human disease. -

Dyskeratosis Congenita 101

Dyskeratosis Congenita 101 Sharon A. Savage, M.D. Chief, Clinical Genetics Branch Clinical Director, Division of Cancer Epidemiology & Genetics Camp Sunshine September 2018 2012 2016 Dyskeratosis Congenita – early descriptions Year Author(s) Reference Atrophia Cutis Reticularis cum Pigmentatione, Dystrophia 1906 Zinsser, F Unguium et Leukoplakia oris, Ikonogr Derm (Kioto), p 219 A Unique Case of Reticular Pigmentation of the Skin with 1910 Engman, MF, Sr Atrophy, Society Transactions, Arch Derm Syph 13:685 Cole, HN, Dyskeratosis Congenita with Pigmentation, Dystrophia 1930 Rauschkolb JE, Unguis, and Leukokeratosis Oris, Arch Derm Syph 21:71 and Toomey J Archives of Dermatology Vol 88, Sept. 1963 People with telomere biology disorders may face multiple medical problems and always Remember: Ø Everyone is different Ø These problems don’t happen to everyone Ø Things change with age Ø We learn more everyday Diagnostic Triad 1. Dysplastic Nails Diagnostic Triad 2. Skin pigmentation Diagnostic Triad 3. Oral leukoplakia Hematopoietic (blood) system Bone marrow failure Failure to produce enough blood cells Myelodysplastic syndrome Abnormal looking blood cells associated with low numbers and leukemia risk Leukemia Cancer of the blood forming cells Respiratory system Head and neck squamous cell cancer Pulmonary fibrosis Pulmonary arterio- venous malformations (AVMs) Abnormal blood vessel formation in lungs Gastrointestinal (GI) system Esophageal stenosis Liver disease Narrowing of the esophagus Fibrosis and/or abnormal blood vessel connections between -

An Update on the Biology and Management of Dyskeratosis Congenita and Related Telomere Biology Disorders

Expert Review of Hematology ISSN: 1747-4086 (Print) 1747-4094 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ierr20 An update on the biology and management of dyskeratosis congenita and related telomere biology disorders Marena R. Niewisch & Sharon A. Savage To cite this article: Marena R. Niewisch & Sharon A. Savage (2019) An update on the biology and management of dyskeratosis congenita and related telomere biology disorders, Expert Review of Hematology, 12:12, 1037-1052, DOI: 10.1080/17474086.2019.1662720 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/17474086.2019.1662720 Accepted author version posted online: 03 Sep 2019. Published online: 10 Sep 2019. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 146 View related articles View Crossmark data Citing articles: 1 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=ierr20 EXPERT REVIEW OF HEMATOLOGY 2019, VOL. 12, NO. 12, 1037–1052 https://doi.org/10.1080/17474086.2019.1662720 REVIEW An update on the biology and management of dyskeratosis congenita and related telomere biology disorders Marena R. Niewisch and Sharon A. Savage Clinical Genetics Branch, Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY Introduction: Telomere biology disorders (TBDs) encompass a group of illnesses caused by germline Received 14 June 2019 mutations in genes regulating telomere maintenance, resulting in very short telomeres. Possible TBD Accepted 29 August 2019 manifestations range from complex multisystem disorders with onset in childhood such as dyskeratosis KEYWORDS congenita (DC), Hoyeraal-Hreidarsson syndrome, Revesz syndrome and Coats plus to adults presenting Telomere; dyskeratosis with one or two DC-related features. -

Genomics of Inherited Bone Marrow Failure and Myelodysplasia Michael

Genomics of inherited bone marrow failure and myelodysplasia Michael Yu Zhang A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2015 Reading Committee: Mary-Claire King, Chair Akiko Shimamura Marshall Horwitz Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Molecular and Cellular Biology 1 ©Copyright 2015 Michael Yu Zhang 2 University of Washington ABSTRACT Genomics of inherited bone marrow failure and myelodysplasia Michael Yu Zhang Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Mary-Claire King Department of Medicine (Medical Genetics) and Genome Sciences Bone marrow failure and myelodysplastic syndromes (BMF/MDS) are disorders of impaired blood cell production with increased leukemia risk. BMF/MDS may be acquired or inherited, a distinction critical for treatment selection. Currently, diagnosis of these inherited syndromes is based on clinical history, family history, and laboratory studies, which directs the ordering of genetic tests on a gene-by-gene basis. However, despite extensive clinical workup and serial genetic testing, many cases remain unexplained. We sought to define the genetic etiology and pathophysiology of unclassified bone marrow failure and myelodysplastic syndromes. First, to determine the extent to which patients remained undiagnosed due to atypical or cryptic presentations of known inherited BMF/MDS, we developed a massively-parallel, next- generation DNA sequencing assay to simultaneously screen for mutations in 85 BMF/MDS genes. Querying 71 pediatric and adult patients with unclassified BMF/MDS using this assay revealed 8 (11%) patients with constitutional, pathogenic mutations in GATA2 , RUNX1 , DKC1 , or LIG4 . All eight patients lacked classic features or laboratory findings for their syndromes. -

Ectodermal Dysplasia (Generic Term)

Ectodermal Dysplasia (generic term) Authors: Doctor Kathleen Mortier1, Professor Georges Wackens1 Creation date: September 2004 Scientific Editor: Professor Antonella Tosti 1Department of stomatology and maxillofacial surgery, AZ VUB Brussels, Belgium [email protected] Definition Clinical classification of Ectodermal dysplasias References Definition Ectodermal dysplasias (EDs) are a heterogeneous group of disorders characterized by developmental dystrophies of ectodermal structures, such as hypohidrosis, hypotrichosis, onychodysplasia and hypodontia or anodontia. About 160 clinically and genetically distinct hereditery ectodermal dysplasias have been cataloged. In the early seventies there existed no definition and no classification. Freire-Maia and Pinheiro tried to put some order in the field of ectodermal dysplasias. Firstly, the group should be defined before an attempt was made to list its conditions. Secondly, the group was so large that it was necessary to split it into several subgroups. So they decided that an ED should present any two of the signs that affected the four structures widely mentioned by the authors who studied the classic EDs – hair, teeth, nails and sweat glands – with or without any other sign (see blow). The system is arbitrary without biological relevance to the pathogenesis and genetics of the specific disorder. However, classification based on clinical signs and symptoms is all that has been available until recently, since the pathogenesis and molecular genetics of the disorder are largely unknown. Clinical classification of Ectodermal dysplasias (Pinheiro and Freire-Maia, 1994) Unknown cause Conditions AD AR XL ? AD? AR? XL? Subgroup 1-2-3-4 1. Christ-Siemens-Touraine (CST) syndrome (MIM 305100; XR BDE 0333; POS 3208; FMP 1) 2. -

Table I. Genodermatoses with Known Gene Defects 92 Pulkkinen

92 Pulkkinen, Ringpfeil, and Uitto JAM ACAD DERMATOL JULY 2002 Table I. Genodermatoses with known gene defects Reference Disease Mutated gene* Affected protein/function No.† Epidermal fragility disorders DEB COL7A1 Type VII collagen 6 Junctional EB LAMA3, LAMB3, ␣3, 3, and ␥2 chains of laminin 5, 6 LAMC2, COL17A1 type XVII collagen EB with pyloric atresia ITGA6, ITGB4 ␣64 Integrin 6 EB with muscular dystrophy PLEC1 Plectin 6 EB simplex KRT5, KRT14 Keratins 5 and 14 46 Ectodermal dysplasia with skin fragility PKP1 Plakophilin 1 47 Hailey-Hailey disease ATP2C1 ATP-dependent calcium transporter 13 Keratinization disorders Epidermolytic hyperkeratosis KRT1, KRT10 Keratins 1 and 10 46 Ichthyosis hystrix KRT1 Keratin 1 48 Epidermolytic PPK KRT9 Keratin 9 46 Nonepidermolytic PPK KRT1, KRT16 Keratins 1 and 16 46 Ichthyosis bullosa of Siemens KRT2e Keratin 2e 46 Pachyonychia congenita, types 1 and 2 KRT6a, KRT6b, KRT16, Keratins 6a, 6b, 16, and 17 46 KRT17 White sponge naevus KRT4, KRT13 Keratins 4 and 13 46 X-linked recessive ichthyosis STS Steroid sulfatase 49 Lamellar ichthyosis TGM1 Transglutaminase 1 50 Mutilating keratoderma with ichthyosis LOR Loricrin 10 Vohwinkel’s syndrome GJB2 Connexin 26 12 PPK with deafness GJB2 Connexin 26 12 Erythrokeratodermia variabilis GJB3, GJB4 Connexins 31 and 30.3 12 Darier disease ATP2A2 ATP-dependent calcium 14 transporter Striate PPK DSP, DSG1 Desmoplakin, desmoglein 1 51, 52 Conradi-Hu¨nermann-Happle syndrome EBP Delta 8-delta 7 sterol isomerase 53 (emopamil binding protein) Mal de Meleda ARS SLURP-1 -

Blueprint Genetics Comprehensive Immune and Cytopenia Panel

Comprehensive Immune and Cytopenia Panel Test code: IM0901 Is a 642 gene panel that includes assessment of non-coding variants. Is ideal for patients with a clinical suspicion of an inborn error of immunity, such as, Primary Immunodeficiency, Bone Marrow Failure Syndrome, Dyskeratosis Congenita, Neutropenia, Thrombocytopenia, Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis, Autoinflammatory Disorders, Complement System Disorder, Leukemia, or Chronic Granulomatous Disease. This panel includes most genes from Primary Immunodeficiency, Severe Combined Immunodeficiency, Complement System Disorder, Bone Marrow Failure Syndrome, Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis, Congenital Neutropenia, Thrombocytopenia, Congenital Diarrhea, Chronic Granulomatous Disease, Diamond-Blackfan Anemia, Fanconi Anemia, Dyskeratosis Congenita, Autoinflammatory Syndrome, and Hereditary Leukemia Panels as well as many other genes associated with inborn errors of immunity. Please note that unlike our other panels, this panel is on our Whole Exome Sequencing platform and cannot be customized. Pricing may vary from our regular panel pricing. About immunodeficiency and cytopenia disorders There is an enormous amount of phenotypic overlap between immunological and hematological disorders, which makes it challenging to know which of these two systems is not functioning properly. Knowing the underlying genetic cause of a person’s clinical diagnosis, especially immunodeficiency, bone marrow failure, neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, autoinflammatory disease, or bone marrow failure can sometime