Cutthroat 26 Copy FINAL AUG

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fools Crow, James Welch

by James Welch Model Teaching Unit English Language Arts Secondary Level with Montana Common Core Standards Written by Dorothea M. Susag Published by the Montana Office of Public Instruction 2010 Revised 2014 Indian Education for All opi.mt.gov Cover: #955-523, Putting up Tepee poles, Blackfeet Indians [no date]; Photograph courtesy of the Montana Historical Society Research Center Photograph Archives, Helena, MT. by James Welch Model Teaching Unit English Language Arts Secondary Level with Montana Common Core Standards Written by Dorothea M. Susag Published by the Montana Ofce of Public Instruction 2010 Revised 2014 Indian Education for All opi.mt.gov #X1937.01.03, Elk Head Kills a Buffalo Horse Stolen From the Whites, Graphite on paper, 1883-1885; digital image courtesy of the Montana Historical Society, Helena, MT. Anchor Text Welch, James. Fools Crow. New York: Viking/Penguin, 1986. Highly Recommended Teacher Companion Text Goebel, Bruce A. Reading Native American Literature: A Teacher’s Guide. National Council of Teachers of English, 2004. Fast Facts Genre Historical Fiction Suggested Grade Level Grades 9-12 Tribes Blackfeet (Pikuni), Crow Place North and South-central Montana territory Time 1869-1870 Overview Length of Time: To make full use of accompanying non-fiction texts and opportunities for activities that meet the Common Core Standards, Fools Crow is best taught as a four-to-five week English unit—and history if possible-- with Title I support for students who have difficulty reading. Teaching and Learning Objectives: Through reading Fools Crow and participating in this unit, students can develop lasting understandings such as these: a. -

“Carried in the Arms of Standing Waves:” the Transmotional Aesthetics of Nora Marks Dauenhauer1

Transmotion Vol 1, No 2 (2015) “Carried in the Arms of Standing Waves:” The Transmotional Aesthetics of Nora Marks Dauenhauer1 BILLY J. STRATTON In October 2012 Nora Marks Dauenhauer was selected for a two-year term as Alaska State Writer Laureate in recognition of her tireless efforts in preserving Tlingit language and culture, as well as her creative contributions to the state’s literary heritage. A widely anthologized author of stories, plays and poetry, Dauenhauer has published two books, The Droning Shaman (1988) and Life Woven With Song (2000). Despite these contributions to the ever-growing body of native American literary discourse her work has been overlooked by scholars of indigenous/native literature.2 The purpose of the present study is to bring attention to Dauenhauer’s significant efforts in promoting Tlingit peoplehood and cultural survivance through her writing, which also offers a unique example of transpacific discourse through its emphasis on sites of dynamic symmetry between Tlingit and Japanese Zen aesthetics. While Dauenhauer’s poesis is firmly grounded in Tlingit knowledge and experience, her creative work is also notable for the way it negotiates Tlingit cultural adaptation in response to colonial oppression and societal disruption through the inclusion of references to modern practices and technologies framed within an adaptive socio-historical context. Through literary interventions on topics such as land loss, environmental issues, and the social and political status of Tlingit people within the dominant Euro-American culture, as well as poems about specific family members, Dauenhauer merges the individual and the communal to highlight what the White Earth Nation of Anishinaabeg novelist, poet and philosopher, Gerald Vizenor, conceives as native cultural survivance.3 She demonstrates her commitment to “documenting Tlingit language and oral tradition” in her role as co-editor, along with her husband, Richard, of the acclaimed series: Classics of Tlingit Oral Literature (47). -

2015 Year in Review

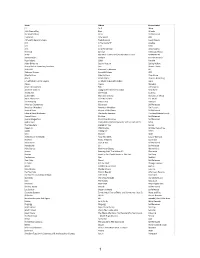

Ar#st Album Record Label !!! As If Warp 11th Dream Day Beet Atlan5c The 4onthefloor All In Self-Released 7 Seconds New Wind BYO A Place To Bury StranGers Transfixia5on Dead Oceans A.F.I. A Fire Inside EP Adeline A.F.I. A.F.I. Nitro A.F.I. Sing The Sorrow Dreamworks The Acid Liminal Infec5ous Music ACTN My Flesh is Weakness/So God Damn Cold Self-Released Tarmac Adam In Place Onesize Records Ryan Adams 1989 Pax AM Adler & Hearne Second Nature SprinG Hollow Aesop Rock & Homeboy Sandman Lice Stones Throw AL 35510 Presence In Absence BC Alabama Shakes Sound & Colour ATO Alberta Cross Alberta Cross Dine Alone Alex G Beach Music Domino Recording Jim Alfredson's Dirty FinGers A Tribute to Big John Pa^on Big O Algiers Algiers Matador Alison Wonderland Run Astralwerks All Them Witches DyinG Surfer Meets His Maker New West All We Are Self Titled Domino Jackie Allen My Favorite Color Hans Strum Music AM & Shawn Lee Celes5al Electric ESL Music The AmazinG Picture You Par5san American Scarecrows Yesteryear Self Released American Wrestlers American Wrestlers Fat Possum Ancient River Keeper of the Dawn Self-Released Edward David Anderson The Loxley Sessions The Roayl Potato Family Animal Hours Do Over Self-Released Animal Magne5sm Black River Rainbow Self Released Aphex Twin Computer Controlled Acous5c Instruments Part 2 Warp The Aquadolls Stoked On You BurGer Aqueduct Wild KniGhts Wichita RecordinGs Aquilo CallinG Me B3SCI Arca Mutant Mute Architecture In Helsinki Now And 4EVA Casual Workout The Arcs Yours, Dreamily Nonesuch Arise Roots Love & War Self-Released Astrobeard S/T Self-Relesed Atlas Genius Inanimate Objects Warner Bros. -

A Descriptive and Comparative Study of Conceptual Metaphors in Pop and Metal Lyrics

UNIVERSIDAD DE CHILE FACULTAD DE FILOSOFÍA Y HUMANIDADES DEPARTAMENTO DE LINGÜÍSTICA METAPHORS WE SING BY: A DESCRIPTIVE AND COMPARATIVE STUDY OF CONCEPTUAL METAPHORS IN POP AND METAL LYRICS. Informe final de Seminario de Grado para optar al Grado de Licenciado en Lengua y Literatura Inglesas Estudiantes: María Elena Álvarez I. Diego Ávila S. Carolina Blanco S. Nelly Gonzalez C. Katherine Keim R. Rodolfo Romero R. Rocío Saavedra L. Lorena Solar R. Manuel Villanovoa C. Profesor Guía: Carlos Zenteno B. Santiago-Chile 2009 2 Acknowledgements We would like to thank Professor Carlos Zenteno for his academic encouragement and for teaching us that [KNOWLEDGE IS A VALUABLE OBJECT]. Without his support and guidance this research would never have seen the light. Also, our appreciation to Natalia Saez, who, with no formal attachment to our research, took her own time to help us. Finally, we would like to thank Professor Guillermo Soto, whose suggestions were fundamental to the completion of this research. Degree Seminar Group 3 AGRADECIMIENTOS Gracias a mi mamá por todo su apoyo, por haberme entregado todo el amor que una hija puede recibir. Te amo infinitamente. A la Estelita, por sus sabias palabras en los momentos importantes, gracias simplemente por ser ella. A mis tías, tío y primos por su apoyo y cariño constantes. A mis amigas de la U, ya que sin ellas la universidad jamás hubiese sido lo mismo. Gracias a Christian, mi compañero incondicional de este viaje que hemos decidido emprender juntos; gracias por todo su apoyo y amor. A mi abuelo, que me ha acompañado en todos los momentos importantes de mi vida… sé que ahora estás conmigo. -

Polish Journal for American Studies Vol. 7 (2013)

TYTUŁ ARTYKUŁU 1 Polish Journal for American Studies Journal for 7 (2013) Polish Vol. | Polish Journal for American Studies Yearbook of the Polish Association for American Studies and the Institute of English Studies, University of Warsaw Vol. 7 (2013) Irmina Wawrzyczek Rethinking the History of the American Revolution: An Interview with Michal Jan Rozbicki Julia Fiedorczuk Marianne Moore’s Ethical Artifice Shelley Armitage Black Looks and Imagining Oneself Richly: The Cartoons of Jackie Ormes Józef Jaskulski The Frontier as Hyperreality in Robert Altman’s Buffalo Bill and the Indians ISSN 1733-9154 Jennifer D. Ryan Re-imagining the Captivity Narrative in Mark Z. Danielewski’s House of Leaves TYTUŁ ARTYKUŁU 1 Polish Journal for American Studies Yearbook of the Polish Association for American Studies and the Institute of English Studies, University of Warsaw Vol. 7 (2013) Warsaw 2013 2 IMIĘ NAZWISKO MANAGING EDITOR Marek Paryż EDITORIAL BOARD Paulina Ambroży, Patrycja Antoszek, Zofia Kolbuszewska, Karolina Krasuska, Zuzanna Ładyga ADVISORY BOARD Andrzej Dakowski, Jerzy Durczak, Joanna Durczak, Andrew S. Gross, Andrea O’Reilly Herrera, Jerzy Kutnik, John R. Leo, Zbigniew Lewicki, Eliud Martínez, Elżbieta Oleksy, Agata Preis-Smith, Tadeusz Rachwał, Agnieszka Salska, Tadeusz Sławek, Marek Wilczyński REVIEWERS FOR VOL. 7 Andrzej Antoszek , Jerzy Durczak, Joanna Durczak, Julia Fiedorczuk, Jacek Gutorow, Grzegorz Kość, Anna Krawczyk-Łaskarzewska, Krystyna Mazur, Zbigniew Mazur, Anna Pochmara ISSN 1733-9154 Copyright by the authors 2013 Polish Association for American Studies, Al. Niepodległości 22, 02-653 Warsaw www.paas.org.pl Publisher: Institute of English Studies, University of Warsaw ul. Nowy Świat 4, 00-497 Warsaw www. angli.uw.edu.pl Typesetting, cover design by Bartosz Mierzyński Cover image courtesy of the Library of Congress, LC-DIG-ppmsca-13707 Nakład: 130 egz. -

June 2020 #211

Click here to kill the Virus...the Italian way INSIDE THIS ISSUE: Table of Contents 1 Notams 2 Admin Reports 3-4-5 Covid19 Experience Flying the Line with Covid19 Paul Soderlind Scholarship Winners North Country Don King Atkins Stratocruiser Contributing Stories from the Members Bits and Pieces-June Gars’ Stories From here on out the If you use and depend on the most critical thing is NOT to RNPA Directory FLY THE AIRPLANE. you must keep your mailing address(es) up to date . The ONLY Instead, you MUST place that can be done is to send KEEP YOUR EMAIL UPTO DATE. it to: The only way we will have to The Keeper Of The Data Base: communicate directly with you Howie Leland as a group is through emails. Change yours here ONLY: [email protected] (239) 839-6198 Howie Leland 14541 Eagle Ridge Drive, [email protected] Ft. Myers, FL 33912 "Heard about the RNPA FORUM?" President Reports Gary Pisel HAPPY LOCKDOWN GREETINGS TO ALL MEMBERS Well the past few weeks and months have been a rude awakening for our past lifestyles. Vacations and cruises cancelled, all the major league sports cancelled, the airline industry reduced to the bare minimum. Luckily, I have not heard of many pilots or flight attendants contracting COVID19. Hopefully as we start to reopen the USA things will bounce back. The airlines at present are running at full capacity but with several restrictions. Now is the time to plan ahead. We have a RNPA cruise on Norwegian Cruise Lines next April. Things will be back to the new normal. -

Shotgun Wedding by Tiffany Zehnal

Shotgun Wedding by Tiffany Zehnal Writer's First Draft May 22, 2006 FADE IN: EXT. A SMALL TEXAS TOWN - EARLY MORNING The kind of town where people get by and then die. The morning sun has no choice but to come up over the horizon. A SQUIRREL... scurries across a telephone line... down a pole... over a "DON'T MESS WITH TEXASS" sticker... into an apartment complex parking lot... EXT. SHERWOOD FOREST APARTMENT COMPLEX ...and under a BLACK EXTENDED CAB PICK-UP TRUCK that faces out of its parking spot. It's filthy. As evident by the dirt graffiti: "F'ing Wash Me!" The driver's side mirror hangs by a metal thread. On the windshield, ONE DEAD GOLDFISH, eyes wide open... ...and in the back window, an EMPTY GUN RACK. INT. BATHROOM A box of AMMUNITION. A pair of female hands with a perfect FRENCH MANICURE loads bullets into a SHOTGUN. One by one. The only jewelry, a THIN, SILVER BAND on the middle finger of her left hand. INT. BEDROOM A clock radio -- the numbers flip from 5:59 to 6:00. COUNTRY MUSIC fills the room as a hand reaches over and HITS the snooze button. A millisecond of silence. An OFF-SCREEN SHOTGUN IS COCKED. The mound in the middle of the bed lifts his eye mask. This is WYATT, 34, handsome in a ruggedly casual never-washes-his- jeans way. He has a SMALL MOLE on his neck which, if you squint, looks like Texas. Wyatt’s all about maintaining the status quo. If he used words like status quo. -

Adam Mackiewicz, University of Łódź, Poland

Teaching American Literature: A Journal of Theory and Practice Winter 2016 (8:2) Native American Identity and Cultural Appropriation in Post-Ethnic Reality Adam Mackiewicz, University of Łódź, Poland Abstract: Not only is the concept of identity a relatively new invention but also it has become an umbrella term including a large set of components that are mistakenly taken for granted. Cultural studies has developed the idea that identities are contradictory and cross-cut. It is believed that identities change according to how subjects are addressed and/or represented. Such an assumption allows for the re-articulation of various and definite components under changeable historical and cultural circumstances. Thus, it may be assumed that identity is something that is created rather than given. Yet in Native American communities identity construction is likely to become more complicated for American Indian identities include not only cultural statuses but also legal ones. Elizabeth Cook-Lynn states that Native American identity quest, as part of tribal nationalism, involves the interest in establishing the myths and metaphors of sovereign nationalism – the places, the mythological beings and the oral tradition. Even though ethnic pluralism and cultural expression help keep various worldviews alive, one should not overlook the issue of various acts of appropriation that result in cultural harm or in a weakened or distorted/misrepresented cultural identity. Key words: Native Americans, identity, cultural appropriation, mythology The concept -

American Book Awards 2004

BEFORE COLUMBUS FOUNDATION PRESENTS THE AMERICAN BOOK AWARDS 2004 America was intended to be a place where freedom from discrimination was the means by which equality was achieved. Today, American culture THE is the most diverse ever on the face of this earth. Recognizing literary excel- lence demands a panoramic perspective. A narrow view strictly to the mainstream ignores all the tributaries that feed it. American literature is AMERICAN not one tradition but all traditions. From those who have been here for thousands of years to the most recent immigrants, we are all contributing to American culture. We are all being translated into a new language. BOOK Everyone should know by now that Columbus did not “discover” America. Rather, we are all still discovering America—and we must continue to do AWARDS so. The Before Columbus Foundation was founded in 1976 as a nonprofit educational and service organization dedicated to the promotion and dissemination of contemporary American multicultural literature. The goals of BCF are to provide recognition and a wider audience for the wealth of cultural and ethnic diversity that constitutes American writing. BCF has always employed the term “multicultural” not as a description of an aspect of American literature, but as a definition of all American litera- ture. BCF believes that the ingredients of America’s so-called “melting pot” are not only distinct, but integral to the unique constitution of American Culture—the whole comprises the parts. In 1978, the Board of Directors of BCF (authors, editors, and publishers representing the multicultural diversity of American Literature) decided that one of its programs should be a book award that would, for the first time, respect and honor excellence in American literature without restric- tion or bias with regard to race, sex, creed, cultural origin, size of press or ad budget, or even genre. -

Purity Ring Bodyache Free Downloadl

Purity Ring Bodyache Free Downloadl 1 / 4 Purity Ring Bodyache Free Downloadl 2 / 4 3 / 4 Print and download in PDF or MIDI Bodyache. A WIP of Purity Ring's bodyache. Apologies for how weird the drum part is transcribed, I'll fix it at a later time.. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Jump to navigation Jump to search. Purity Ring discography. Studio albums, 2. Music videos, 8. Singles, 11. Purity Ring are a Canadian electronic music duo formed in 2010 consisting of Megan James ... Release date: March 3, 2015; Label: 4AD; Formats: Digital download, CD, LP.. Purity Ring - Bodyache (LIONE Remix). 0.00 | 4:24. Previous track Play or pause track Next track. Enjoy the full SoundCloud experience with our free app.. Check out both LIONE & Purity Ring at their social spots below and be sure to cop the free download of LIONE's uplifting remix of Bodyache .... Another Eternity is the second studio album by Canadian electronic music duo Purity Ring. ... From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Jump to navigation ... "Bodyache" was released as the album's third single on February 26, 2015. The music video ... "another eternity: Purity Ring: MP3-Downloads" (in German). Amazon.de.. Purity Ring. pink lightning · tour · Store · lyrics. Womb. April third. Pre-order / Pre-save · Google+.. Purity Ring - Another Eternity zip downloadPurity Ring - Begin Again leak ... leak downloadPurity Ring - Bodyache mp3 downloadPurity Ring - Dust Hymn leak ... Full Album leak Free Download link MP3 ZIP RARArtist: Purity RingAlbum: .... Listen to Purity Ring's top songs like begin again, push pull, Fineshrine, browse upcoming concerts and discover similar DJs on EDM Hunters. -

1988 Memorandum

0 Indi~J{~rtt 'A~ements C ~aY.1988 S. R. Martin, Jr., Lab. II, Rm. 22S3, Phone: X6009, 6248 Sponsor #872lC In order to capitalize upon the strengths of Evergreen group study and independent/individual work and to avoid their weaknesses, we've agreed to a kind of hybrid working format for the fall term. We'll do some group work--seminar and regular critique group meetings, but we'll emphasize individual efforts in reading and writing. Based upon our discussions, the following agreements seem most reasonable. Group Readings Everyone will read the following: Shadow Dancing in the U.S.A., Michael Ventura Beloved, Toni Morrison Paco's Story, Larry Heinemann The Entire Short Story Sections of Two Literary Journals (to be selected by the faculty member) These texts will comprise the subject matter for five (S) bi- weekly seminar sessions. They will be the only materials that we'll all read together. Individual Readings Everyone should read a variety and significant quantity of additional texts--short stories, novels, craft books, etc. I require only that each person read the entire short story sections of five (S) literary journals to be chosen by the individual reader. All other readings are matters of individual choice, though the quantity should equal at least that of a book per week of work. Writing Reading Journals Everyone should keep a journal on all readings completed, whether for seminar discussions or not. Make entries in whatever notebook you prefer, but I will not read sloppy, illegible pages (and I'd prefer not to read looseleaf pages). -

Ascoltare Con Gli Occhi Il Linguaggio Non Verbale E Le Differenze Culturali

Corso di Laurea magistrale in Scienze Del Linguaggio Tesi di Laurea: Ascoltare con gli Occhi Il Linguaggio Non Verbale e le Differenze Culturali Relatore Ch. Prof. Fabio Caon Correlatore Ch. Prof. Graziano Serragiotto Laureando Marco Munari Matricola 820853 Anno Accademico 2014 / 2015 ASCOLTARE CON GLI OCCHI IL LINGUAGGIO NON VERBALE E LE DIFFERENZE CULTURALI INDICE: INTRODUCTION 1. INTERCULTURAL COMMUNICATIVE COMPETENCE 2. NON-VERBAL COMMUNICATION 2.1 KINESICS 2.1.1 FACE AND EMOTIONS 2.1.1.1 HAPPINESS 2.1.1.2 SADNESS 2.1.1.3 FEAR 2.1.1.4 ANGER 2.1.1.5 DISGUST 2.1.1.6 SURPRISE 2.1.1.7 COUNTERFEITING EMOTIONS 2.1.2 THE GAZE 2.1.2.1 GAZE AND MUTUAL GAZE 2.1.2.1.1 REGULATING THE FLOW OF COMMUNICATION 2.1.2.1.2 MONITORING FEEDBACK 2.1.2.1.3 DISPLAYING COGNITIVE ACTIVITY 2.1.2.1.4 EXPRESSING EMOTIONS 2.1.2.1.5 COMMUNICATING THE TYPE OF RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN THE INTERLOCUTORS 2.1.2.2 DILATION AND CONTRACTION OF PUPILS 2.1.2.3 THE GLANCE AS GUIDE TO THE COGNITIVE PROCESSES 2.1.3 HANDS AND ARMS 2.1.3.1 INDIPENDENT GESTURES 2.1.3.2 DIPENDENT GESTURES 2.1.3.2.1 GESTURES BOUND TO REFERENT/SPEAKER 2.1.3.2.2 GESTURES INDICATIVE OF REFERENT/SPEAKER RELATIONSHIP 2.1.3.2.3 PUNCTUATION GESTURES 2.1.3.2.4 INTERACTIVE GESTURES 2.1.3.3 SELF-HANDLING 2.1.3.4 FREQUENCY OF GESTURES 2.1.3.5 INTERACTIVE SYNCHRONY 2.1.3.6 WIDESPREAD GESTURES 2.1.4 PHYSICAL CONTACT 2.1.5 LEGS AND FEET 2.1.6 DIRECTION OF THE BODY AND POSTURE 2.1.6.1 INTERPERSONAL ATTITUDES 2.1.7 SMELLS AND NOISES OF THE BODY 2.2 PROSSEMICA 2.2.1 LO SPAZIO PERSONALE 2.2.2 INVASIONE DEL TERRITORIO 2.2.3 DENSITÀ ED AFFOLLAMENTO 2.2.4 COMPORTAMENTI SPAZIALI 2.2.4.1 IN ASCENSORE 2.2.4.2 IN MACCHINA 2.2.4.3 DA SEDUTI 2.3 VESTEMICA 2.4 OGGETTEMICA 3 IL LINGUAGGIO PARAVERBALE 3.1 ESPRESSIONE DELLE EMOZIONI 3.2 ATTEGGIAMENTI INTERPERSONALI 3.3 INFORMAZIONI SUL MITTENTE 3.3.1 PERSONALITÀ 3.3.2 CLASSE SOCIALE 3.3.3 SESSO 3.3.4 ETÀ 3.4 PROSODIA E COMPRENSIONE 3.5 PROSODIA E PERSUASIONE 3.6 PROSODIA E TURNI DI PAROLA 3.7 PAUSE E SILENZI 4 NATURAL VS.