DP A4 Anglais:Mise En Page 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Révélations 2013

L’Académie des César et CHAUMET présentent RÉVÉLATIONS 2013 par DOMINIQUE ISSERMANN 2013 LA RELIGIEUSE de Guillaume Nicloux 2013 AU BOUT DU CONTE d’Agnès Jaoui 2012 UNE BOUTEILLE À LA MER de Thierry Binisti 2012 CHERCHEZ HORTENSE de Pascal Bonitzer 2012 À MOI SEULE de Frédéric Videau 2010 LE MARIAGE À TROIS de Jacques Doillon 2010 TOUTES LES FILLES PLEURENT de Judith Godrèche Agathe BONITZER 2009 UN CHAT, UN CHAT de Sophie Fillières 2008 LA BELLE PERSONNE de Christophe Honoré 2008 LE GRAND ALIBI de Pascal Bonitzer 2006 JE PENSE À VOUS de Pascal Bonitzer 2003 LES SENTIMENTS de Noémie Lvovsky 2003 UN HOMME UN VRAI d’Arnaud et Jean-Marie Larrieu 2001 VA SAVOIR de Jacques Rivette 1996 TROIS VIES ET UNE SEULE MORT de Raoul Ruiz 2012 TÉLÉ GAUCHO de Michel Leclerc Félix MOATI 2011 LIVIDE d’Alexandre Bustillo et Julien Maury 2009 LOL de Lisa Azuelos 2013 DES GENS QUI S’EMBRASSENT de Danièle Thompson 2012 BYE-BYE BLONDIE de Virginie Despentes 2012 COSIMO E NICOLE de Francesco Amato 2012 LES INFIDÈLES de Fred Cavayé, Alexandre Courtes, Michel Hazanavicius, Emmanuelle Bercot, Eric Lartigau, Jean Dujardin, Gilles Lellouche Clara PONSOT 2011 POUPOUPIDOU de Gérald Hustache-Mathieu 2010 BUS PALLADIUM de Christopher Thompson 2010 COMPLICES de Frédéric Mermoud 2009 LA GRANDE VIE d’Emmanuel Salinger 2008 LA POSSIBILITÉ D’UNE ÎLE de Michel Houellebecq 2013 IL EST PARTI DIMANCHE de Nicole Garcia Benjamin LAVERHNE 2012 RADIOSTARS de Romain Lévy DIVIN ENFANT d’Olivier Doran (à venir) 2013 ZE BIG SLIP de Caroline Chomienne India HAIR 2013 JACKY AU ROYAUME DES -

André Téchiné: Ein filmobibliographisches Dossier 2012

Repositorium für die Medienwissenschaft Dieter Merlin; Hans Jürgen Wulff André Téchiné: Ein filmobibliographisches Dossier 2012 https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/12768 Veröffentlichungsversion / published version Buch / book Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Merlin, Dieter; Wulff, Hans Jürgen: André Téchiné: Ein filmobibliographisches Dossier. Hamburg: Universität Hamburg, Institut für Germanistik 2012 (Medienwissenschaft: Berichte und Papiere 136). DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/12768. Erstmalig hier erschienen / Initial publication here: http://berichte.derwulff.de/0136_12.pdf Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Creative Commons - This document is made available under a creative commons - Namensnennung - Nicht kommerziell - Keine Bearbeitungen 4.0/ Attribution - Non Commercial - No Derivatives 4.0/ License. For Lizenz zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu dieser Lizenz more information see: finden Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Medienwissenschaft / Hamburg: Berichte und Papiere 136, 2012: André Téchiné. Redaktion und Copyright dieser Ausgabe: Dieter Merlin u. Hans J. Wulff. ISSN 1613-7477. URL: http://www.rrz.uni-hamburg.de/Medien/berichte/arbeiten/0136_12.pdf Letzte redaktionelle Änderung: 28.7.2012. André Téchiné: Ein filmobibliographisches Dossier Zusammengestellt v. Dieter Merlin und Hans J. Wulff Inhalt: André Téchiné: Ein einleitender Kommentar / Dieter Merlin Filmo-Bibliographie / Dieter Merlin, Hans J. Wulff 1. Filmographie / Titelregister 2. Texte von und Interviews mit Téchiné 2.1 Filminterviews mit Téchiné 2.2 Texte von Téchiné 2.3 Interviews (chronologisch) 3. Literatur zu Téchiné allgemein 3.1 Monographien 3.2 Analytische Artikel 3.3 Kleine Artikel, Gesamtdarstellungen etc. 3.4 Filmlexika mit Kurzinfos zu Téchiné 3.5 Websites zu Téchiné 4. -

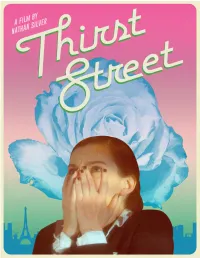

Thirst Street Press-Notes-Web.Pdf

A PSYCHOSEXUAL BLACK COMEDY Press Contacts: Kevin McLean | [email protected] Kara MacLean | [email protected] USA/FRANCE / 2017 / 83 minutes / English with French Subtitles / Color / DCP + Blu-ray Alone and depressed after the suicide of her lover, American flight attendant Gina (Lindsay Burdge, A TEACHER) travels to Paris and hooks up with nightclub bartender Jerome (Damien Bonnard, STAYING VERTICAL) on her layover. But as Gina falls deeper into lust and opts to stay in France, this harmless rendezvous quickly turns into unrequited amour fou. When Jerome’s ex Clémence (Esther Garrel) reenters the picture, Gina is sent on a downward spiral of miscommunication, masochism, and madness. Inspire by European erotic dramas from the 70’s, THIRST STREET burrows deep into the delirious extremes we go to for love. DIRECTOR’S STATEMENT THIRST STREET brings together two of my longest-standing, most nagging obsessions: France and Don Quixote. I spent my junior year of high school as an exchange student in France, in a foolish attempt to live out my dream of being a French poet. I realized within days that I wasn’t French (and never would be) and that poetry wasn’t for me, but nearly two decades later, I still find myself just as obsessed with the place. Our protagonist Gina is my Quixote, unflinching in her quest to find that most important (and ridiculous) thing: love. The emotions of THIRST STREET are just as hysterical as those in my last few movies, but the style here is much more fluid and deliberate, with surreal lighting increasingly threatening to devour the picture. -

Feature Films LIBRARY Latest Releases

feature films LIBRARY latest releases TWO OF US BLIND SPOT by Filippo Meneghetti by Pierre Trividic & Patrick-Mario Bernard With: Barbara Sukowa, Martine Chevallier, Léa Drucker With: Jean-Christophe Folly, Isabelle Carré, Golshifteh Farahani Nina and Madeleine, two retired women, are secretly deeply in love for decades. From everybody's point of view, including Dominick always had the power to turn invisible but he chose Madeleine's family, they are simply neighbors living on the to keep it secret and barely used it. One day, his ability to top floor of their building. They come and go between their control it gets out of his hands, throwing his life and loves into two apartments, sharing the tender delights of everyday turmoil… life together. Until the day their relationship is turned upside down by an unexpected event leading Madelein's daughter to slowly unveil the truth about them. Paprika Films - Artémis Productions - Tarantula Ex Nihilo - Les Films De Pierre France - Benelux / 2019 France / 2019 ANGOULÊME - PALM SPRINGS - HONORABLE MENTION WHATEVER HAPPENED JURY PRIZE SAF TORONTO TO MY REVOLUTION by Ali Vatansever by Judith Davis With: Saadet Işil Akşoy, Erol Afşin, Onur Buldu, Ümmü Putgül With: Judith Davis, Malik Zidi, Claire Dumas Istanbul, 2018. Urban transformation is sweeping away local Angèle, a young and restless activist, never stops crusading communities. Kamil and his wife Remziye are threatened to for social justice, losing sight of her friends, family and love lose their house. When Kamil suddenly disappears, Remziye in the process. have to face the consequences of his actions. Agat Films - Apsara Films Terminal Film - 2Pilots Film - 4 Proof Film France / 88' / 2018 Turkey - Germany - Romania / 102' / 2018 TALLINN BLACK NIGHTS TRANSFRONTEIRA PERIFERIAS - SLAM RAIVA AUDIENCE AWARD by Partho Sen-Gupta by Sérgio Tréfaut SIX SOPHIA AWARDS INCLUDING BEST FILM With: Adam Bakri, Rachael Blake, Abbey Azziz With: Isabel Ruth, Leonor Siveira, Hugo Bentes Ricky is a young Arab Australian whose peaceful suburban Portugal, 1950. -

Guillaume DEPARDIEU

Guillaume DEPARDIEU Guillaume Depardieu est né le 7 avril 1971 dans le 14e arrondissement de Paris. Il est le fils des acteurs Gérard Depardieu et Élisabeth Guignot (ex Depardieu). Il est aussi le frère aîné de l'actrice Julie Depardieu, le demi-frère de Roxanne Depardieu, fille de l'actrice Karine Silla-Pérez, et le demi-frère de Jean Depardieu, fils de la comédienne Hélène Bizot. Enfant, son père l'emmène avec lui quelquefois sur des plateaux de tournage et le fait figurer dans quelques-uns de ses films : Pas si méchant que ça de Claude Goretta en 1974, Jean de Florette de Claude Berri en 1986 et Cyrano de Bergerac de Jean-Paul Rappeneau en 1990. Il vit une adolescence perturbée par différents problèmes, notamment la toxicomanie. Il fréquente durant cette période l'École Saint-Martin-de- France (lycée) à Pontoise. À l'âge de 17 ans, en 1988, il est condamné à trois ans d'emprisonnement pour usage, importation et trafic d'héroïne. Il est incarcéré à la Maison d'arrêt de Bois-d'Arcy. Après dix-huit mois d'incarcération il obtiendra une libération conditionnelle. Il sera condamné par la suite à plusieurs reprises pour outrages, rébellions et pour diverses infractions routières. Guillaume Depardieu était un « garçon distilbène », dont les caractéristiques alléguées sont dépressions sévères, anxiété, troubles du comportement alimentaire, alcoolisme, schizophrénie, etc. : « Quand ma mère était enceinte de moi, elle prenait du Distilbène.». Mais aucun lien de causalité n'a été avéré dans son cas. En 1991, âgé de vingt ans, il joue son premier grand rôle dans le film Tous les matins du monde d'Alain Corneau où il incarne le joueur de viole de gambe Marin Marais jeune, tandis que son père occupe le rôle de celui-ci après son accession à la Cour de Louis XIV. -

Edinburgh Glasgow London Aberdeen Cambridge Dumfries Dundee Durham Inverness Manchester St Andrews Stirling Warwick

Edinburgh Glasgow London Aberdeen Cambridge Dumfries Dundee Durham Inverness Manchester St Andrews Stirling Warwick 8 November – 20 December 2009 www.frenchfilmfestival.org.uk INDEX GUESTS The Welcome Pack 4 / 5 PREVIEW 7 THE FATHER OF MY CHILDREN / LE PÈRE DE MES ENFANTS (15) 8 BIENVENUE A PROPHET / UN PROPHÈTE (18) 8 SÉRAPHINE (PG) 9 WELCOME (15) 9 WELCOME TOTALLY TATI AND HULOT AND TATI: THE ALTER EGO HAS LANDED 11 / 12 / 13 JOUR DE FÊTE (U) 15 Your annual fête of French cinema is back in its regular November slot. M HULOT'S HOLIDAY / LES VACANCES DE MONSIEUR HULOT (U) 15 Besides delivering the best of contemporary cinéma français from established MON ONCLE (U) 16 PLAYTIME (U) 16 auteurs to new talents, the 2009 selection of the 17th edition of the French TRAFIC (U) 17 Film Festival UK from 8 November to 20 December will feature tributes to two PARADE (U) 17 diverse but legendary figures: Jacques Tati and Jean Eustache about whom THE MAGNIFICENT TATI (U) 18 TATI SHORTS (U) 18 much more on the pages to follow. PANORAMA 21 BELLAMY (15) 22 Panorama gathers titles featuring the crème de la crème of French stars THE BEAUTIFUL PERSON / LA BELLE PERSONNE (15) 22 among them Gérard Depardieu, Nathalie Baye, Josiane Balasko, Catherine CRIME IS OUR BUSINESS / LE CRIME EST NOTRE AFFAIRE (15) 23 Frot, André Dussollier, Gérard Jugnot, Jean-Pierre Darroussin, Fabrice A FRENCH GIGOLO / CLIENTE (18) 23 I ALWAYS WANTED TO BE A GANGSTER / J’AI TOUJOURS RÊVÉ D’ÊTRE UN GANGSTER (15) 24 Luchini, Chiara Mastroianni, and Emmanuel Mouret as well as a clin d’oeil on THE GIRL FROM MONACO / LA FILLE DE MONACO (15) 24 novelist Françoise Sagan through the remarkable performance of Sylvie Testud. -

Afm Product Guide 2003

3DD ENTERTAINMENT 3DD Entertainment, 190 Camden High Street, London, UK NW1 8QP. Tel: 011.44.207.428.1800. Fax: 011 44 207 428 1818. e-mail: [email protected]. Website: www.3dd-entertainment.co.uk Company Type: Distributor At AFM: Dominic Saville (CEO), Charlotte Parton (Director of Sales), James Anderson (Sales Executive), Acquisition Executive: Dominic Saville (CEO) Office: Suite # 334, Tel: 310.458.6700, Mobile: 44 (0)7961 318 665 Film THE ICEMAN COMETH DRAMA Language: ENGLISH Director: JOHN FRANKENHEIMER Producer: ELY LANDAU Co-Production Partners: Cast:LEE MARVIN, JEFF BRIDGES, FREDERIC MARCH Delivery Status: COMPLETED Year of Production: 1973 Country of Origin: USA/UK Budget: NOT AVAILABLE Based on acclaimed playwright Eugene O'Neill's brilliant stage drama, the patrons of The Last Chance Saloon gather for an evening to contemplate their lost faith and dreams. Film A DELICATE BALANCE DRAMA Language: ENGLISH Director: TONY RICHARDSON Producer: ELY LANDAU Co-Production Partners: Cast: KATHARINE HEPBRUN, LEE REMICK, PAUL SCOFIELD Delivery Status: COMPLETED Year of Production: 1973 Country of Origin: USA Budget: NOT AVAILABLE Based on a play by Edward Albee, a dysfunctional couple discovers that they have more than they can handle when a family gathering turns chaotic. Film BUTLEY DRAMA Language: ENGLISH Director: HAROLD PINTER Producer: ELY LANDAU, OTTO PLASCHKES Co-Production Partners: Cast: ALAN BATES, JESSICA TANDY, MICHAEL BYRNE Delivery Status: COMPLETED Year of Production: 1973 Country of Origin: UK Budget: NOT AVAILABLE A self-loathing and misanthropic teacher's life takes a tragic turn when his lover betrays him and his ex-wife remarries, in the screen adaptation of Simon Gray's play. -

Découvrir L'album Collector [PDF]

re?ve?lations 1- sednaoui:Mise en page 1 12/01/08 21:42 Page 1 Daniel Lundh Stéphanie Sokolinski Fu’Ad Aït Aattou Grégoire Leprince-Ringuet Académie des Arts et Techniques du Cinéma Chaumet SH O W M E Dans cette série de portraits où il se montre ému par l’énergie des jeunes acteurs sélectionnés par l’Académie des César, Sednaoui choisit de suspendre l’heure du jugement pour tresser à tous une couronne. Ses compositions sont un hommage à la profession de l’acteur en ce qu’elle contredit toute prétention à l’essence au profit du perpétuel changement : multiplicité des rôles, des émo- Audrey Dana Paco Boublard tions, des masques. Retenant des compressions de César qu’elles ne sont pas sans rapport avec sa volonté de n an sm os Gr y ém él rth SHOWME condenser les mouvements jusqu’à leur faire exprimer une image du temps, il tresse les corps Ba précieux et ornemente les visages pour forger diadèmes et couronnes comme autant de fa- buleux bijoux. Refusant le partage entre l’instant donné à voir et tous ceux laissés pour non RÉVÉLATIONS CÉSAR 2008 vus et affirmant à son tour que passer outre à l’intégrité familière des figures est la seule pos- sibilité de saisir toutes leurs potentialités. Robert Albouker Photographies par Stéphane Sednaoui ST É PH AN E SE DN AO UI photogra phe er ti us mo De s aï An l ne ae H e èl Ad s vi a D th di Ju e èr ch la B se ui Lo y le ro T il Cyr re?ve?lations 1- sednaoui:Mise en page 1 12/01/08 21:42 Page 7 Constance Rousseau Thomas Dumerchez Terry Nimajimbe Emilie de Preissac Clémence Poésy Sylvain Dieuaide Marie -

Catalogue 2021

PYRAMIDE INTERNATIONAL CATALOGUE 2021 CONTENTS INDEX BY FILMS 2 HIGHLIGHTS 17 DIRECTORS’ COLLECTIONS 35 FILMS 59 INDEX BY FILMS AVAILABLE IN HD 424 INDEX BY DIRECTORS 434 INDEX BY ACTORS 450 INDEX BY FILMS 57 000 KM BETWEEN US 60 ANGELE AND TONY 72 57 000 KM ENTRE NOUS ANGÈLE ET TONY Delphine Kreuter Alix Delaporte ANNA 73 A Nikita Mikhalkov ANTONIO’S GIRLFRIEND 74 ABUSE OF WEAKNESS 61 LA PETITE AMIE D’ANTONIO ABUS DE FAIBLESSE Manuel Poirier Catherine Breillat APACHES 75 ACTORS ANONYMOUS 62 LES APACHES LES ACTEURS ANONYMES Thierry De Peretti Benoît Cohen APPRENTICE 76 AFTER THE WAR 63 LES APPRENTIS DOPO LA GUERRA Pierre Salvadori Annarita Zambrano AS HE COMES 77 ALEXANDRIA... NEW YORK 64 COMME IL VIENT Youssef Chahine Christophe Chiesa ALL IS FORGIVEN 65 TOUT EST PARDONNÉ Mia Hansen-Løve B ALL THE FINE PROMISES 66 BAB EL WEB 78 TOUTES CES BELLES PROMESSES Merzak Allouache Jean-Paul Civeyrac BABY BALLOON 79 AMAZING CATFISH, THE 67 Stefan Liberski LOS INSOLITOS PECES GATO Claudia Sainte-Luce BACK HOME 80 REVENIR AMBITIOUS 68 Jessica Palud LES AMBITIEUX Catherine Corsini BARBER OF SIBERIA, THE 81 SIBIRSKIY TSIRYULNIK AMIN 69 Nikita Mikhalkov Philippe Faucon BARNABO OF THE MOUNTAINS 82 AMONG ADULTS 70 BARNABO DELLE MONTAGNE ENTRE ADULTES Mario Brenta Stéphane Brizé BED, THE 83 ANATOMY OF HELL 71 LE LIT ANATOMIE DE L’ENFER Marion Hänsel Catherine Breillat BEIJING BICYCLE 84 Wang XiaoShuai 2 INDEX BY FILMS BELLE EPINE 85 BREATH OF LIFE 100 Rebecca Zlotowski L’ORDRE DES MÉDECINS David Roux BENARES 86 Barlen Pyamootoo BRIDGET 101 Amos Kollek -

Avant Que J'oublie

AVANT QUE J’OUBLIE un film de Jacques Nolot ELIA FILMS et ID DISTRIBUTION présente AVANT QUE J’OUBLIE un film de Jacques Nolot France - 2007 - 1h48 - Couleur 35mm / 1.66 / Dolby SR DISTRIBUTION PRESSE ID DISTRIBUTION Agnès Chabot 6, Cité Paradis 6, rue de l’École de Médecine 75010 Paris PROGRAMMATION 75006 Paris T 01 53 34 90 20 T 01 53 34 90 25 T 01 44 41 13 48 F 01 42 47 11 24 [email protected] [email protected] Photos téléchargeables sur le site: www.iddistribution.com SYNOPSIS Pierre, 58 ans, prisonnier de son passé, a de plus en plus de mal avec la solitude, avec le temps, avec le monde extérieur, a recourt à des psychotropes, s’enferme chez lui, seul lieu où il est le moins mal, dans l’attente d’une inspiration, n’arrive plus à écrire, a rendez-vous pour déjeuner avec son ami, une relation vieille de 30 ans, un ami qui fut un papa, une maman, une banque, l’ami ne viendra pas, Pierre se confronte à la police... à la famille, à la maladie... seul face à lui-même... se ressaisira avec humour et distance... croise chez son avocat un ami de bar... parlent de leur jeunesse, avec l’aide de son psy retrouve l’inspiration. Accompagné d’un gigolo, ira au bout de ses fantasmes. NOTE D’INTENTION Après LA CHATTE À DEUX TÊTES, qui parle de l’errance de Pierre dans un cinéma porno... Je ne savais pas comment aborder la suite... Comme toujours, mon « travail » est une continuation du même personnage.. -

Contemporary French Queer Cinema: Explicit Sex and the Politics of Normalization

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 8-18-2015 12:00 AM Contemporary French Queer Cinema: Explicit Sex and the Politics of Normalization Joanna K. Smith The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Dr. Joe Wlodarz The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Film Studies A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Master of Arts © Joanna K. Smith 2015 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Smith, Joanna K., "Contemporary French Queer Cinema: Explicit Sex and the Politics of Normalization" (2015). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 3113. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/3113 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CONTEMPORARY FRENCH QUEER CINEMA: EXPLICIT SEX AND THE POLITICS OF NORMALIZATION MONOGRAPH by Joanna Knight Smith Graduate Program in Film Studies A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Joanna Knight Smith 2015 Abstract This thesis examines how recent French queer films may mirror, interrogate and engage with sexual politics in France. The key political changes include the 1999 Pacte Civil de Solidarité legislation and the legalization of same-sex marriage in 2013. The thesis focuses on French queer films which are sexually explicit, including simulated and unsimulated sex acts. -

![Découvrir L'album Collector [PDF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7524/d%C3%A9couvrir-lalbum-collector-pdf-9187524.webp)

Découvrir L'album Collector [PDF]

2 un projet présenté par l’Académie des Arts et Techniques du Cinéma en partenariat avec CHANEL page en Curious Gold leaf sans impression Révélati ns 2018 Deniz Gamze Ergüven Réalisatrice du film des Révélations et de la série de photographies 6 Anne Combaz photographe © CHANEL Alain Terzian Président de l’Académie des Arts et Techniques du Cinéma Les Révélations témoignent chaque année d’une nouvelle ardeur embrassant le Cinéma français. Porteurs d’un souffle audacieux, ces visages de demain enrichissent déjà de manière brillante l’art cinématographique d’aujourd’hui. Le projet Révélations réunit les comédiennes et comédiens sélectionnés par le Comité Révélations de l’Académie des Arts et Techniques du Cinéma. Il met en lumière et en images ces nouveaux talents incandescents qui s’apprêtent à briller sur nos écrans pour de nombreuses années. Pour sa douzième édition, le projet Révélations a fait appel à Deniz Gamze Ergüven dont la caméra dans Mustang, son premier film récompensé aux César en 2016 et nommé aux Oscars la même année, a su mettre en lumière la liberté et l’audace d’une jeunesse indocile. En filmant aujourd’hui ces 36 Révélations, elle s’applique à capter la poésie d’un groupe mué par la liberté de s’exprimer et de créer. Le film qu’elle nous propose souligne l’unité et l’harmonie émanant avec force de ces acteurs en devenir…. Les Révélations 2018 se placent également sous le signe de la nouveauté en élaborant un partenariat inédit avec la Maison CHANEL. Tout comme l’Académie des César, CHANEL s’implique depuis de nombreuses années dans la reconnaissance et la mise en avant de jeunes talents, et trouve une place de choix au sein de ce projet ambitieux.