The Resurrection of Frederic Myers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Psychic Phenomena and the Mind–Body Problem: Historical Notes on a Neglected Conceptual Tradition

Chapter 3 Psychic Phenomena and the Mind–Body Problem: Historical Notes on a Neglected Conceptual Tradition Carlos S. Alvarado Abstract Although there is a long tradition of philosophical and historical discussions of the mind–body problem, most of them make no mention of psychic phenomena as having implications for such an issue. This chapter is an overview of selected writings published in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries literatures of mesmerism, spiritualism, and psychical research whose authors have discussed apparitions, telepathy, clairvoyance, out-of-body experiences, and other parapsy- chological phenomena as evidence for the existence of a principle separate from the body and responsible for consciousness. Some writers discussed here include indi- viduals from different time periods. Among them are John Beloff, J.C. Colquhoun, Carl du Prel, Camille Flammarion, J.H. Jung-Stilling, Frederic W.H. Myers, and J.B. Rhine. Rather than defend the validity of their position, my purpose is to docu- ment the existence of an intellectual and conceptual tradition that has been neglected by philosophers and others in their discussions of the mind–body problem and aspects of its history. “The paramount importance of psychical research lies in its demonstration of the fact that the physical plane is not the whole of Nature” English physicist William F. Barrett ( 1918 , p. 179) 3.1 Introduction In his book Body and Mind , the British psychologist William McDougall (1871–1938) referred to the “psychophysical-problem” as “the problem of the rela- tion between body and mind” (McDougall 1911 , p. vii). Echoing many before him, C. S. Alvarado , PhD (*) Atlantic University , 215 67th Street , Virginia Beach , VA 23451 , USA e-mail: [email protected] A. -

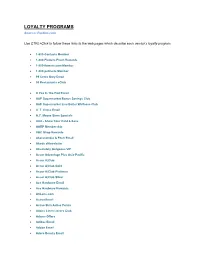

LOYALTY PROGRAMS Source: Perkler.Com

LOYALTY PROGRAMS Source: Perkler.com Use CTRL+Click to follow these links to the web pages which describe each vendor’s loyalty program. 1-800-Contacts Member 1-800-Flowers Fresh Rewards 1-800-flowers.com Member 1-800-petmeds Member 99 Cents Only Email 99 Restaurants eClub A Pea In The Pod Email A&P Supermarket Bonus Savings Club A&P Supermarket Live Better Wellness Club A. T. Cross Email A.C. Moore Store Specials AAA - Show Your Card & Save AARP Membership ABC Shop Rewards Abercrombie & Fitch Email Abode eNewsletter Absolutely Gorgeous VIP Accor Advantage Plus Asia-Pacific Accor A|Club Accor A|Club Gold Accor A|Club Platinum Accor A|Club Silver Ace Hardware Email Ace Hardware Rewards ACLens.com Activa Email Active Skin Active Points Adairs Linen Lovers Club Adams Offers Adidas Email Adobe Email Adore Beauty Email Adorne Me Rewards ADT Premium Advance Auto Parts Email Aeropostale Email List Aerosoles Email Aesop Mailing List AETV Email AFL Rewards AirMiles Albertsons Preferred Savings Card Aldi eNewsletter Aldi eNewsletter USA Aldo Email Alex & Co Newsletter Alexander McQueen Email Alfresco Emporium Email Ali Baba Rewards Club Ali Baba VIP Customer Card Alloy Newsletter AllPhones Webclub Alpine Sports Store Card Amazon.com Daily Deals Amcal Club American Airlines - TRAAVEL Perks American Apparel Newsletter American Eagle AE REWARDS AMF Roller Anaconda Adventure Club Anchor Blue Email Angus and Robertson A&R Rewards Ann Harvey Offers Ann Taylor Email Ann Taylor LOFT Style Rewards Anna's Linens Email Signup Applebee's Email Aqua Shop Loyalty Membership Arby's Extras ARC - Show Your Card & Save Arden B Email Arden B. -

The Sanity of Art. the Sanity of Art: an Exposure of the Current Nonsense About Artists Being Degenerate

The Sanity of Art. The Sanity of Art: An Exposure of the Current Nonsense about Artists being Degenerate. By Ber. nard Shaw : : : : The New Age Press 140 Fleet St., London. 1908 Entered at Library of Congress, United States of America. All rights reserved. Preface. HE re-publication of this open letter to Mr. Benjamin Tucker places me, Tnot for the first time, in the difficulty of the journalist whose work survives the day on which it was written. What the journalist writes about is what everybody is thinking about (or ought to be thinking about) at themoment of writing. To revivehis utterances when everybodyis thinking aboutsomething else ; when the tide of public thought andimagination has turned ; when the front of the stage is filled with new actors ; when manylusty crowers have either survived their vogueor perished with it ; when the little men you patronized have become great, and the great men you attacked have been sanctified and pardoned by popularsentiment in the tomb : all these inevitables test the quality of your I journalismvery severely. Nevertheless, journalism can claim to be the highest formof literature ; for all the highest literature is journalism. The writer who aims atproducing the platitudes which are“not for an age, butfor all time ” has his reward in being unreadable in all ages ; whilst Platoand Aristophanes trying to knock some sense into the Athens oftheir day, Shakespearpeopling that same Athens with Elizabethan mechanics andWarwickshire hunts, Ibsen photo- graphing the local doctors- and vestrymen of a Norwegian parish, Carpaccio painting the life of St. Ursula exactly as if she were a lady living in the next street to him, are still alive and at home everywhere among the dust and ashes of many thousands of academic, punctilious, most archaeologically correct men of letters and art who spent their lives haughtily avoiding the journal- ist’s vulgar obsession with the ephemeral. -

Blavatsky on the Introversion of Mental Vision

Madame Blavatsky on the introversion of mental vision Blavatsky on the introversion of mental vision v. 17.11, www.philaletheians.co.uk, 8 May 2018 Page 1 of 5 BLAVATSKY SPEAKS SERIES INTROVERSION OF MENTAL VISION First published in The Theosophist, Vol. V, No. 5 (53), February 1884, pp. 107-8. Republished in Blavatsky Collected Writings, (INTROVERSION OF MENTAL VISION) VI pp. 135-38. The thought-reading sensitive obtains only an inverted mental picture of the object given him to read. Some interesting experiments have recently been tried by Mr. F.W.H. Myers1 and his colleagues of the Psychic Research Society of London, which, if properly examined are capable of yielding highly important results. The experiments referred to were on their publication widely commented upon by the newspaper Press. With the details of these we are not at present concerned; it will suffice for our purpose to state for the benefit of readers unacquainted with the experiments, that in a very large majority of cases, too numerous to be the result of mere chance, it was found that the thought- reading sensitive obtained but an inverted mental picture of the object given him to read. A piece of paper, containing the representation of an arrow, was held before a carefully blind-folded thought-reader and its position constantly changed, the thought-reader being requested to mentally see the arrow at each turn. In these cir- cumstances it was found that when the arrow-head pointed to the right, it was read off as pointing to the left, and so on. -

The Science of Mediumship and the Evidence of Survival

Rollins College Rollins Scholarship Online Master of Liberal Studies Theses 2009 The cS ience of Mediumship and the Evidence of Survival Benjamin R. Cox III [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.rollins.edu/mls Recommended Citation Cox, Benjamin R. III, "The cS ience of Mediumship and the Evidence of Survival" (2009). Master of Liberal Studies Theses. 31. http://scholarship.rollins.edu/mls/31 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Rollins Scholarship Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master of Liberal Studies Theses by an authorized administrator of Rollins Scholarship Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Science of Mediumship and the Evidence of Survival A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Liberal Studies by Benjamin R. Cox, III April, 2009 Mentor: Dr. J. Thomas Cook Rollins College Hamilton Holt School Master of Liberal Studies Winter Park, Florida This project is dedicated to Nathan Jablonski and Richard S. Smith Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................................... 1 The Science of Mediumship.................................................................... 11 The Case of Leonora E. Piper ................................................................ 33 The Case of Eusapia Palladino............................................................... 45 My Personal Experience as a Seance Medium Specializing -

Master of Arts

RICE UNIVERSITY The Classification of Deat h-Related Experiences: A Novel Approach to the Spe ctrum of Near-Death, Coincidental-Death, andBy Empat hetic-Death Events Antoinette M. von dem Hagen A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE Master of Arts APPROVED, THESIS COMMITTEE Claire Fanger Committee Chair Associate Professor of Religion Co-Director of M.A. Studies Jeffrey Kripal Jeffrey Kripal (Apr 26, 2021 19:01 CDT) Jeffrey Kripal J. Newton Rayzor Professor of Religion Associate Dean, Humanities Niki Clements Watt J. and Lilly G. Jackson Assistant Professor of Religion Director, Undergraduate Studies Religion HOUSTON, TEXAS April 2021 ABSTRACT The Classification of Death-Related Experiences: A Novel Approach to the Spectrum of Near-Death, Coincidental-Death, and Empathetic-Death Events by Antoinette M. von dem Hagen In 1866, Edmund Gurney, Frederic Myers and Frank Podmore published Phantasms of the Living, which included descriptions of “crisis apparitions” where someone who was dying was “seen” by someone who was unaware of this fact. Since then, the concept of Near-Death Experiences (“NDE’s”) have become an increasingly popular subject in both nonfiction works and medical research, yet little attention has been paid to crisis apparitions. Here, I argue that NDE’s and crisis apparitions—which I separate into the categories of Coincidental-Death and Empathetic-Death Experiences—contain similar phenomenological attributes. These Death- Related Experiences (“DRE’s”) thus occur along a spectrum; the empathetic relationship between the decedent and the experiencer acts as the determinative element. This definition and categorization of DRE’s is a novel concept in super normal research. -

VAN Satellite 2019: Challenging the Status

VAN Satellite 2019 Keynote summary Session: Challenging the status quo – the Sanity story Speaker: Ray Itaoui Ray Itaoui is the son of Lebanese migrant factory workers. His parents wanted the best start for their children – so much so that Ray and his older brother were left with his grandparents in Lebanon for the first four years of his life while his parents established themselves in Australia. Ray had a strict upbringing, with a heavy focus on study. Sport was not an option. "We lived across from a park and going to play with our friends was a mission. Most times we were told no." He rebelled, started hanging out with the wrong crowd and was expelled from Sydney's Granville Boys High School in his final year. However, he was able to complete year 12 in Dubbo, where he had a long-distance relationship with a girl whose mother happened to be a teacher. Her family let Ray live with them while he attended school to complete his HSC. "That was a real pivotal point in my life,” recalls Ray. It took me out of my environment. I learnt so much about Australia, about family. It was a unique opportunity." After finishing school, he enrolled at university to study psychology but soon realised it wasn't for him. Instead, he returned to McDonald's, where he'd worked part-time when he was at school. For 13 years he stayed at McDonald's until he became a store manager. But when the promotions dried up, Ray began job hunting. In 2001, Ray joined Sanity as an area manager and worked his way up to Queensland state manager. -

The Anchor, Volume 52.06: December 7, 1938

Hope College Hope College Digital Commons The Anchor: 1938 The Anchor: 1930-1939 12-7-1938 The Anchor, Volume 52.06: December 7, 1938 Hope College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.hope.edu/anchor_1938 Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Recommended Citation Repository citation: Hope College, "The Anchor, Volume 52.06: December 7, 1938" (1938). The Anchor: 1938. Paper 17. https://digitalcommons.hope.edu/anchor_1938/17 Published in: The Anchor, Volume 52, Issue 6, December 7, 1938. Copyright © 1938 Hope College, Holland, Michigan. This News Article is brought to you for free and open access by the The Anchor: 1930-1939 at Hope College Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Anchor: 1938 by an authorized administrator of Hope College Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Frosh in Charge of Page 3 Ijupc Calkpc Andior Frosh in Charge of Page 3 i -• Volume UI Fifty-second Year at Publication Hope College, Holland, Mich., December 7,1938 Number 6 1) Voorhees, Alcor, Jtorrjpt Student Council AS I SEE IT W.A.L. Begin • BY • Plan Announces Christmas Spirit Blase Levi! Commons Room Several Christmas parties have been planned by Women's organ- Although we have spent many Cooperating Organizations izations on campus to celebrate the a long hour of interesting "Bull holiday season. Meet To Complete Sessions" discussing that seemingly The annual Christmas party of inexhaustible riddle, "Hitlerism/' Ci Arrangements . Alcor, the senior girls' Honor Soci- we shall tackle it once again in a ety, will be celebrated tonight at slightly varied form. -

Sobre Edmund Gurney.German Berrios.P65

Rev. Latinoam. Psicopat. Fund., São Paulo, 16(2), 273-279, jun. 2013 Sobre Edmund Gurney* German E. Berrios O artigo que se segue é importante por ter redirecionado o estudo das alucinações para longe do contexto médico estreito que havia sido construído por 273 Esquirol, Baillarger e Michéa (Berrios, 1996).1 A morte prematura de seu autor, um homem de Cambridge de raro talento, privou a epistemologia inglesa de um paladino importante. Palavras-chave: Alucinações, Esquirol, Baillarger, Micheá *Tradução de Lazslo A. Ávila; revisão técnica da tradução de Ana Maria G. R. Oda. 1Há uma quantidade enorme de trabalhos sobre a “história” das alucinações (Ey, 1973). Variam desde publicações antigas considerando como uma “descoberta” a descrição, agru- pamento e nomeação das alucinações, até relatos escritos desde a perspectiva da moder- na história da ciência que veem a conceituação das alucinações durante a primeira parte do século XIX como parte do processo mais amplo de construção do novo conceito de “sintoma mental” (Berrios, 1985, 1996, 2005). REVISTA LATINOAMERICANA DE PSICOPATOLOGIA FUNDAMENTAL Edmund Gurney nasceu em 23 de março de 1847 no seio das classes médias cultas. Um espírito inquieto (com toda a probabilidade, uma personalidade ciclotímica) e um estudante infatigável, ele inicialmente cursou Literatura Clás- sica e depois Medicina na Universidade de Cambridge e, fi- nalmente, Direito em Londres. Durante todo esse período, ele estava tentando, sem sucesso, se tornar um pianista con- certista (Gauld, 2004). Foi, por um tempo, membro associa- do (fellow) do Trinity College (Cambridge), onde pesquisou incansavelmente (Myers, 1888-1889) e escreveu importan- tes contribuições para a teoria musical, psicologia e pesqui- sa psíquica. -

Parapsychology: the "Spiritual" Science

Parapsychology: The "Spiritual" Science James E. Alcock Parapsychology, once the despised outcast of a materialistic- forces, which are said to lie beyond the realm of ordinary ally oriented orthodoxy, may now claim pride of place among nature, at least insofar as it is known by modern science, has the spiritual sciences, for it was parapsychology which not been an easy one. Yet, despite the slings and arrows of pioneered the exploration of the world beyond the senses. sometimes outrageous criticism, many men and women have dedicated themselves over the years to the pursuit of psi and to —J. L. Randall, Parapsychology and the Nature of Life the task of attempting to convince skeptical scientists of the necessity of taking the psi hypothesis seriously. There must be some important motivation to continue to hether in séance parlors, in "haunted" houses, in believe in the reality of psi, and to continue to pursue its study. simple laboratories using decks of cards and rolling In this article, it will be argued that this motivation is, for most dice, or in sophisticated research centers employing W parapsychologists at least, a quasi-religious one. Such a view- equipment of the atomic age, the search for psychic ("psi") point is bound to anger many in parapsychology who see them- forces has been under way, in the name of science, for over a selves simply as dedicated researchers who are on the trail of century. The quest to demonstrate the reality of these putative important phenomena that normal science has refused to study. However, were that the case, one would expect to see much more disillusionment and abandonment, given the paucity of James E. -

Spirited Defense: William James and the Ghost Hunters

SI N-D 2006 pgs 9/27/06 9:46 AM Page 59 BOOK REVIEWS view of the Titus case consequently is Spirited Defense: that it is a decidedly solid document in favor of the admission of a supernatural William James and the faculty of seership” (5). Blum is prepared to leave readers Ghost Hunters with the distinct impression that only JOE NICKELL Mrs. Titus’s clairvoyant powers could explain such a remarkable case. She Ghost Hunters: William James and the Search for Scientific writes: “When I started this book, I saw Proof of Life After Death. By Deborah Blum. The Penguin myself as the perfect author to explore Press, New York, 2006. ISBN 1-59420-090-4. 370 pp. the supernatural, and a career science Hardcover, $25.95. writer anchored in place with the sturdy shoes of common sense.” But her ivaling the new burst of rational- Hampshire, set out one October morn- research changed the way she thought: ism among philosophers and sci- ing in 1898 for the mill where she “I still don’t aspire to a sixth sense, I like entists that was spawned by worked. She left a trail of footprints in R being a science writer, still grounded in Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution in the frost but they soon disappeared, reality. I’m just less smug than I was the latter nineteenth century, a counter along with Bertha herself. One hundred when I started, less positive of my right- movement of “spiritualism” and “unex- and fifty people searched nearby woods ness” (323). -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 105 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 105 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION Vol. 144 WASHINGTON, TUESDAY, JULY 28, 1998 No. 103 Senate The Senate met at 9:45 a.m., and was the Senate may proceed as a body to move to passage of this legislation, and called to order by the President pro the Rotunda to pay our proper respects then go to an appropriations bill. I tempore (Mr. THURMOND). to the two fallen U.S. Capitol police- yield the floor. men and their families. The Senate f PRAYER will recess again today from 2:45 p.m. RESERVATION OF LEADER TIME The Chaplain, Dr. Lloyd John until 3:45 p.m. so Members may attend Ogilvie, offered the following prayer: the memorial service for these two he- The PRESIDING OFFICER (Mr. Gracious Father, whose mercies are roes. ENZI). Under the previous order, the new every morning, we praise You for With regard to the Senate's schedule leadership time is reserved. Your faithfulness. We exalt You with a this morning, the Senate will resume f consideration of the credit union bill, rendition of the words of that wonder- with 15 minutes for debate remaining CREDIT UNION MEMBERSHIP ful old hymn, ``Great is Your faithful- on the Shelby amendment regarding ACCESS ACT ness! Great is Your faithfulness! Morn- small business exemptions. At approxi- The PRESIDING OFFICER. Under ing by morning, new mercies we see; all mately 10 a.m; the Senate will proceed the previous order, the Senate will now we have needed Your hand has pro- to vote on, or in relation to, the Shelby resume consideration of H.R.