The Sanity of Art. the Sanity of Art: an Exposure of the Current Nonsense About Artists Being Degenerate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

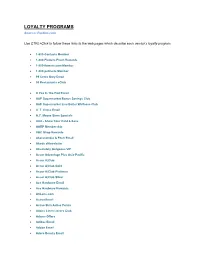

LOYALTY PROGRAMS Source: Perkler.Com

LOYALTY PROGRAMS Source: Perkler.com Use CTRL+Click to follow these links to the web pages which describe each vendor’s loyalty program. 1-800-Contacts Member 1-800-Flowers Fresh Rewards 1-800-flowers.com Member 1-800-petmeds Member 99 Cents Only Email 99 Restaurants eClub A Pea In The Pod Email A&P Supermarket Bonus Savings Club A&P Supermarket Live Better Wellness Club A. T. Cross Email A.C. Moore Store Specials AAA - Show Your Card & Save AARP Membership ABC Shop Rewards Abercrombie & Fitch Email Abode eNewsletter Absolutely Gorgeous VIP Accor Advantage Plus Asia-Pacific Accor A|Club Accor A|Club Gold Accor A|Club Platinum Accor A|Club Silver Ace Hardware Email Ace Hardware Rewards ACLens.com Activa Email Active Skin Active Points Adairs Linen Lovers Club Adams Offers Adidas Email Adobe Email Adore Beauty Email Adorne Me Rewards ADT Premium Advance Auto Parts Email Aeropostale Email List Aerosoles Email Aesop Mailing List AETV Email AFL Rewards AirMiles Albertsons Preferred Savings Card Aldi eNewsletter Aldi eNewsletter USA Aldo Email Alex & Co Newsletter Alexander McQueen Email Alfresco Emporium Email Ali Baba Rewards Club Ali Baba VIP Customer Card Alloy Newsletter AllPhones Webclub Alpine Sports Store Card Amazon.com Daily Deals Amcal Club American Airlines - TRAAVEL Perks American Apparel Newsletter American Eagle AE REWARDS AMF Roller Anaconda Adventure Club Anchor Blue Email Angus and Robertson A&R Rewards Ann Harvey Offers Ann Taylor Email Ann Taylor LOFT Style Rewards Anna's Linens Email Signup Applebee's Email Aqua Shop Loyalty Membership Arby's Extras ARC - Show Your Card & Save Arden B Email Arden B. -

VAN Satellite 2019: Challenging the Status

VAN Satellite 2019 Keynote summary Session: Challenging the status quo – the Sanity story Speaker: Ray Itaoui Ray Itaoui is the son of Lebanese migrant factory workers. His parents wanted the best start for their children – so much so that Ray and his older brother were left with his grandparents in Lebanon for the first four years of his life while his parents established themselves in Australia. Ray had a strict upbringing, with a heavy focus on study. Sport was not an option. "We lived across from a park and going to play with our friends was a mission. Most times we were told no." He rebelled, started hanging out with the wrong crowd and was expelled from Sydney's Granville Boys High School in his final year. However, he was able to complete year 12 in Dubbo, where he had a long-distance relationship with a girl whose mother happened to be a teacher. Her family let Ray live with them while he attended school to complete his HSC. "That was a real pivotal point in my life,” recalls Ray. It took me out of my environment. I learnt so much about Australia, about family. It was a unique opportunity." After finishing school, he enrolled at university to study psychology but soon realised it wasn't for him. Instead, he returned to McDonald's, where he'd worked part-time when he was at school. For 13 years he stayed at McDonald's until he became a store manager. But when the promotions dried up, Ray began job hunting. In 2001, Ray joined Sanity as an area manager and worked his way up to Queensland state manager. -

The Anchor, Volume 52.06: December 7, 1938

Hope College Hope College Digital Commons The Anchor: 1938 The Anchor: 1930-1939 12-7-1938 The Anchor, Volume 52.06: December 7, 1938 Hope College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.hope.edu/anchor_1938 Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Recommended Citation Repository citation: Hope College, "The Anchor, Volume 52.06: December 7, 1938" (1938). The Anchor: 1938. Paper 17. https://digitalcommons.hope.edu/anchor_1938/17 Published in: The Anchor, Volume 52, Issue 6, December 7, 1938. Copyright © 1938 Hope College, Holland, Michigan. This News Article is brought to you for free and open access by the The Anchor: 1930-1939 at Hope College Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Anchor: 1938 by an authorized administrator of Hope College Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Frosh in Charge of Page 3 Ijupc Calkpc Andior Frosh in Charge of Page 3 i -• Volume UI Fifty-second Year at Publication Hope College, Holland, Mich., December 7,1938 Number 6 1) Voorhees, Alcor, Jtorrjpt Student Council AS I SEE IT W.A.L. Begin • BY • Plan Announces Christmas Spirit Blase Levi! Commons Room Several Christmas parties have been planned by Women's organ- Although we have spent many Cooperating Organizations izations on campus to celebrate the a long hour of interesting "Bull holiday season. Meet To Complete Sessions" discussing that seemingly The annual Christmas party of inexhaustible riddle, "Hitlerism/' Ci Arrangements . Alcor, the senior girls' Honor Soci- we shall tackle it once again in a ety, will be celebrated tonight at slightly varied form. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 105 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 105 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION Vol. 144 WASHINGTON, TUESDAY, JULY 28, 1998 No. 103 Senate The Senate met at 9:45 a.m., and was the Senate may proceed as a body to move to passage of this legislation, and called to order by the President pro the Rotunda to pay our proper respects then go to an appropriations bill. I tempore (Mr. THURMOND). to the two fallen U.S. Capitol police- yield the floor. men and their families. The Senate f PRAYER will recess again today from 2:45 p.m. RESERVATION OF LEADER TIME The Chaplain, Dr. Lloyd John until 3:45 p.m. so Members may attend Ogilvie, offered the following prayer: the memorial service for these two he- The PRESIDING OFFICER (Mr. Gracious Father, whose mercies are roes. ENZI). Under the previous order, the new every morning, we praise You for With regard to the Senate's schedule leadership time is reserved. Your faithfulness. We exalt You with a this morning, the Senate will resume f consideration of the credit union bill, rendition of the words of that wonder- with 15 minutes for debate remaining CREDIT UNION MEMBERSHIP ful old hymn, ``Great is Your faithful- on the Shelby amendment regarding ACCESS ACT ness! Great is Your faithfulness! Morn- small business exemptions. At approxi- The PRESIDING OFFICER. Under ing by morning, new mercies we see; all mately 10 a.m; the Senate will proceed the previous order, the Senate will now we have needed Your hand has pro- to vote on, or in relation to, the Shelby resume consideration of H.R. -

Rethinking Routing and Peering in the Era of Vertical Integration of Network Functions

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2019 Rethinking Routing and Peering in the era of Vertical Integration of Network Functions Prasun Kanti Dey University of Central Florida Part of the Computer Engineering Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Doctoral Dissertation (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Dey, Prasun Kanti, "Rethinking Routing and Peering in the era of Vertical Integration of Network Functions" (2019). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 6709. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/6709 RETHINKING ROUTING AND PEERING IN THE ERA OF VERTICAL INTEGRATION OF NETWORK FUNCTIONS by PRASUN KANTI DEY M.S. University of Nevada Reno, 2016 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering in the College of Engineering and Computer Science at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Fall Term 2019 Major Professor: Murat Yuksel c 2019 Prasun Kanti Dey ii ABSTRACT Content providers typically control the digital content consumption services and are getting the most revenue by implementing an “all-you-can-eat” model via subscription or hyper-targeted ad- vertisements. Revamping the existing Internet architecture and design, a vertical integration where a content provider and access ISP will act as unibody in a sugarcane form seems to be the recent trend. -

In Westfield's Mayoralty and Open Debate on the the School Is Still Accepting Geography, History of the Debris

O\ THE WESTFIELD LEADER o J*e Leading and Most Widely Circulated Weekly Newspaper In Union County c2 •< m o » n K « Second Clusi* I'OSIUKP I'libhslied 1HTY-FIFTH YEAR — NO. 8 at WeBtfifW. N. J. WESTFIELD, NEW JERSEY, THURSDAY, OCTOEER 3, 1974 i-rv Thiimdiiy 28 Pages—15 Cents o • M 4 or) ic Waste" Program Resumes Tuesday Williams on Town Land: Leslie to Seek waste" "Aggressive Maintenance, I . l at 6 p.m. Tuesday at the Public Reelection of B of E Works Center at the corner Conservative Development" of North Ave. and Crossway Clark Leslie has an- realities. I will spend the PI. with a revised schedule In a major policy ment, "to implement a nounced that he will seek statement on parks. next four months seeking calling for year-round program of periodic reelection to the Westfield the support of everyone operation and two evening recreation and the use of furloughing of athletic fields Board of Education. Mr. undeveloped town-owned interested in quality collection times each week. to allow needed turf Leslie stated, "I have education." land, Alex Williams regeneration." decided to run again NEW SCHEDULE: Republican candidate for Mr. Leslie has served as Tuesday and Thursday The Brightwood Park and because I consider service mayor, has called for an Boynton Avenue sites, both to our community to be both vice president of the board evenings, 6-8 p.m.; Satur- aggressive maintenance day, 10 a.m. - 4 p.m. except undeveloped town-owned an obligation and an honor. for the past two years. -

PDF Download Finding Sanity: John Cade, Lithium and the Taming Of

FINDING SANITY: JOHN CADE, LITHIUM AND THE TAMING OF BIPOLAR DISORDER PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Greg De Moore,Ann Westmore | 304 pages | 01 Apr 2017 | Allen & Unwin | 9781760113704 | English | St Leonards, Australia Finding Sanity: John Cade, Lithium and the Taming of Bipolar Disorder PDF Book Fitzroy, Victoria , Australia. This is prelude to an entire nine-page case history of Bill Brand, the first of ten patients John Cade would treat with lithium. If significant kidney problems show up in the initial testing, lithium should be prescribed only with great care and close monitoring. Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation vs. This time he failed to benefit from ECT. Bipolar Disorder With Anxious Distress. Following the British tradition John completed a postdoctoral degree in medicine. Managing symptoms and preventing complications begins with a thorough knowledge of your illness. There are 2 toxic substances in urine: urea and uric acid. Random House, Gitlin M. One was a female patient in her late 50s who had developed side effects within a day of starting treatment. When first seen as outpatients people were required to bring a relative or significant other with them who was interviewed separately to provide a broad perspective. My fellow resident David Taylor and I befriended George, a lonely bachelor, and welcomed him into our homes, catering to a gargantuan omnivorous appetite. Mercifully Jack recovered fully, possibly due to the discovery of a new drug, cortisone. Are your symptoms caused by something else? Mood Disorders Society of Canada. While he was convalescing, John fell in love with one of his nurses, Jean. For his contribution to psychiatry, he was awarded a Kittay International Award in with Mogens Schou from Denmark , and he was invited to be a Distinguished Fellow of the American College of Psychiatrists. -

Asx Announcement – for Immediate Release – 11 December 2007

ASX ANNOUNCEMENT – FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE – 11 DECEMBER 2007 ENTERS AGREEMENT WITH SANITY, VIRGIN AND HMV Digital media, entertainment and advertising company, Swish Group announces that its subsidiary Swish AmpHead has entered into a distribution agreement with leading Australasian entertainment retailers Sanity, Virgin and HMV to distribute part of Swish AmpHead’s significant physical CD music catalogue through their Australia wide retail networks. The agreement with Sanity, Virgin and HMV is the second major distribution deal by Swish AmpHead for the distribution of physical product since the move into CD distribution was announced in June this year. The Sanity, Virgin and HMV agreement also comes after Swish AmpHead in October announced a significant extension of its relationship with USA-based independent music distributor The Orchard, the world's largest distributor of independent music. Swish Group is delighted to have reached agreement with the Sanity, Virgin and HMV groups said the Company’s Managing Director, Mr Cary Stynes. “Swish AmpHead is continuing to sign new Australian bands each week and under this agreement we will now be able to distribute CDs to Sanity, Virgin and HMV as well as distributing new tracks through our extensive existing online digital channels,” Mr Stynes said. Swish AmpHead through its association with The Orchard has access to an enormous range of music from over 77 countries, incorporating a catalogue of more than one million music titles from 20,000 artists and 6,000 labels. The physical distribution music deal with Sanity, Virgin and HMV complements the existing Swish AmpHead online digital music distribution business which has been experiencing significant quarter on quarter growth from its clients including I-tunes, Telstra Bigpond, Vodafone, Ericsson and most other major online music sites. -

Spring COLLEGES & UNIVERSITIES RELEASES

2020 NEW Spring COLLEGES & UNIVERSITIES RELEASES © 2019 CTMG, Inc. All Rights Reserved. © Focus Features LLC. © 2019 Disney Enterprises Inc. © Lions Gate Entertainment, Inc. © 2019 Paramount Pictures © 2019 WBEI TM & © DC Comics COLLEGES & Spring2020 UNIVERSITIES Create an Movie ExperienceExceptional Access the latest planning and promotional resources for your event at swank.com. • Customer Tips for Generate Movie Event Success BUZZ Suggested Effectively getting the word out is key to your program’s success. Students Resources: are routinely bombarded with advertisements and event opportunities, so it’s important to think outside the box with your promotions. Movies • that deploy unconventional methods of promotion are not only the most Customizable Schedules SWANK ACCOUNT popular, but also the most memorable. EXECUTIVE Free Promo Toolkit: • Social Media Tips EVENT AND To make things easier, we put PROMO GUIDE together a free, customizable promotional toolkit you can STICKERS download on our website under • Pre-Show Slides INSPIRE the “Promotions Resources” tab. SCHEDULES U It features: Whether you have a 4, 6, 8, 12 or 16 FALL 2019 Movies title schedule, just click on the one you LOCATION & SCREENING DETAILS Movie Name Movie Name Time Time need and start filling it out! Date Date d. e v r e s e r s . t c h n g i I r , l t n Al . t n nme E i . a t os r er t B n r E e n e r t a a G W Remember to download each template, s 9 n 1 o 0 i 2 L © save as, and open in Adobe Acrobat! © Movie Name Movie Name STICKERS Time Time Date Date d. -

This File Was Downloaded From

This is the author’s version of a work that was submitted/accepted for pub- lication in the following source: Fanning, Jonathon P, Wesley, Allan J, Platts, David G, Walters, Darren L, Eeles, Eamonn M, Seco, Michael, Tronstad, Oystein, Strugnell, Wendy, Barnett, Adrian G., Clarke, Andrew J, Bellapart, Judith, Vallely, Michael P, Tesar, Peter J, & Fraser, John F (2014) The silent and apparent neurological injury in transcatheter aortic valve implantation study (SANITY) : concept, design and rationale. BMC Cardiovascular Disorders, 14(1), pp. 45-55. This file was downloaded from: http://eprints.qut.edu.au/79721/ c c 2014 Fanning et al.; licensee BioMed Central Ltd This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly credited. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedica- tion waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated. Notice: Changes introduced as a result of publishing processes such as copy-editing and formatting may not be reflected in this document. For a definitive version of this work, please refer to the published source: http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2261-14-45 Trial Designs The Silent and Apparent Neurological Injury in Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation (SANITY) Study : Concept, Design and rationale Authors: Dr. Jonathon P. Fanning BSc, MBBS*†δ Dr. Allan J. Wesley MBChB, FRANZCR† Mr. Michael Seco Dr. Eamonn Eeles MBBS, MRCP, MSc†δ Mr. -

Allison Eden Studios

ADVOCACY May 2017 Evergreen spends quite a lot of time and energy advocating on behalf of local firms. Much of the work we do benefits the industrial business community as a whole, such as our participation in public planning on The board and staff here at Evergreen work hard to serve the businesses of industrial North Brooklyn every transportation issues like truck routes and bike lanes. 2016’s biggest industrial community issues include advocacy on the proposed enhanced business area near the waterfront, advising the Department of City year, and 2016 was no exception. In 2016, Evergreen staff served more than 210 individual businesses. We Planning’s North Brooklyn Study, participating in the Bushwick Community Planning process, and serving obtained $610,000.00 in financing for 3 local firms. We managed 22,450 square feet of affordable industrial on a variety of community committees such as the Newtown Creek Community Advisory Group and the L real estate to retain more manufacturing jobs in our community. And staff helped 31 businesses navigate Train Coalition. government agencies resulting in 25 successful outcomes! More than 90 firms sent over 250 attendees to our social mixers, 129 firms attended informational workshops and 64 firms received one-on-one assistance Evergreen also advocates on behalf of individual businesses to help navigate government agencies on a from Evergreen staff. variety of issues such as permits, tickets, graffiti removal, illegal dumping, utilities and signage. Overall, we helped 31 businesses navigate government agencies resulting in 25 successful outcomes! Activities included installation of loading zone signage, street resurfacing, abandoned vehicles, equipment permits, 2016 was a year of continued change in our industrial community and in our own organization. -

Businesses Account Number DBA Name Address Line 1 Line 2 City State Zip Code 18550 I'm YOUR HANDYMAN 3105 HERRICK PL PUEBLO

All Businesses Account Number DBA Name Address Line 1 Line 2 City State Zip Code 18550 I'M YOUR HANDYMAN 3105 HERRICK PL PUEBLO CO 81003 09215 #1 A LIFESAFER OF COLORADO, INC 810 S PORTLAND AVE PUEBLO CO 81001 15724 **SAND HILL CONSTRUCTION LLC 2119 COURT ST PUEBLO CO 81003 12045 1 800 WATER DAMAGE 3100 GRANADA BLVD PUEBLO CO 81005 17303 1 STORY LLC 16359 260TH ST GRUNDY CENTER IA 50638 15058 1-800 CONTACTS INC 66 E WARDSWORTH PARK DR DRAPER UT 84020 19401 1-DERFUL ROOFING & RESTORATION 9858 W GIRTON DR LAKEWOOD CO 80227 19321 10 TIGERS KUNG FU 121 BROADWAY AVE PUEBLO CO 81004 00556 13TH STREET BARBER SHOP 1205 N ELIZABETH PUEBLO CO 81003 11491 1A SMART START INC 4850 PLAZA DR IRVING TX 75063 06805 1ST ALERT SECURITY 301 N MAIN ST STE 304A PUEBLO CO 81003 18822 1ST PRIORITY ROOFING 714 VENTURA ST SUITE B AURORA CO 80011 18547 1ST RATE APPLIANCE 928 S SANTA FE AVE PUEBLO CO 81006 18302 1ST RATE SERVICE PLUMBING 225 S SIESTA DR PUEBLO WEST CO 81007 09342 21ST CENTURY BUILDERS 2401 W 11TH ST PUEBLO CO 81003 19065 29TH ST. DETAIL 1803 W 29TH ST PUEBLO CO 81008 16834 2ND STREET GARAGE EAST 1640 E 2ND ST PUEBLO CO 81001 08061 3 MARGARITAS 3620 N FREEWAY PUEBLO CO 81008 09485 3 T SYSTEMS 5990 GREENWOOD PLAZA BLVD, SUITE 350 GREENWOOD VILLACO 80111 19005 3308 INC 2275 DOWNEND ST COLORADO SPRINGCO 80910 16997 3BELOW 224 S UNION AVE PUEBLO CO 81003 12700 3D SYSTEMS INC 333 THREE D SYSTEMS CIRCLE ROCKHILL SC 29730 14536 3FORM INC 2300 SOUTH 2300 WEST STE B SALT LAKE CITY UT 84119 04150 3M COMPANY 3M CENTER ST PAUL MN 55144 10696 3SI SECURITY SYSTEMS