The Huguenots of South Africa in Documents and Commemoration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Drakenstein Heritage Survey Reports

DRAKENSTEIN HERITAGE SURVEY VOLUME 1: HERITAGE SURVEY REPORT October 2012 Prepared by the Drakenstein Landscape Group for the Drakenstein Municipality P O BOX 281 MUIZENBERG 7950 Sarah Winter Tel: (021) 788-9313 Fax:(021) 788-2871 Cell: 082 4210 510 E-mail: [email protected] Sarah Winter BA MCRP (UCT) Nicolas Baumann BA MCRP (UCT) MSc (OxBr) D.Phil(York) TRP(SA) MSAPI, MRTPI Graham Jacobs BArch (UCT) MA Conservation Studies (York) Pr Arch MI Arch CIA Melanie Attwell BA (Hons) Hed (UCT) Dip. Arch. Conservation (ICCROM) Acknowledgements The Drakenstein Heritage Survey has been undertaken with the invaluable input and guidance from the following municipal officials: Chantelle de Kock, Snr Heritage Officer Janine Penfold, GIS officer David Delaney, HOD Planning Services Anthea Shortles, Manager: Spatial Planning Henk Strydom, Manager: Land Use The input and comment of the following local heritage organizations is also kindly acknowledged. Drakenstein Heritage Foundation Paarl 300 Foundation LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS The following abbreviations have been used: General abbreviations HOZ: Heritage Overlay Zone HWC: Heritage Western Cape LUPO: Land Use Planning Ordinance NHRA: The National Heritage Resources act (Act 25 of 1999) PHA: Provincial Heritage Authority PHS: Provincial Heritage Site SAHRA: The South African Heritage Resources Agency List of abbreviations used in the database Significance H: Historical Significance Ar: Architectural Significance A: Aesthetic Significance Cx: Contextual Significance S: Social Significance Sc: Scientific Significance Sp: Spiritual Significance L: Linguistic Significance Lm: Landmark Significance T: Technological Significance Descriptions/Comment ci: Cast Iron conc.: concrete cor iron: Corrugated iron d/s: double sliding (normally for sash windows) fb: facebrick med: medium m: metal pl: plastered pc: pre-cast (normally concrete) s/s: single storey Th: thatch St: stone Dating 18C: Eighteenth Century 19C: Nineteenth Century 20C: Twentieth Century E: Early e.g. -

Part 2 Performance

PROGRAMME PART 2 PERFORMANCE The services rendered by the Cultural Commission are aligned with the duties and powers of the Commission as set out in the Western Cape Cultural Commission and Cultural Councils Act, 1998 (Act 14 of 1998). G o a l K ey Perf orm an ce Ta rg e t Perf o rman c e Re s ul ts Rea s on f or Va r i a n c e I n d i c a t o r Letting cultural facili- Optimal use of Facilities in use for at least Facilities used for appro x i- N o n e ties placed under the facilities by org a n i- 45 000 people-days mately 67 479 people-days supervision of the sations for the Commission by the p reservation, pro- Minister for the motion and devel- p res erv a tio n , p ro m o- opment of culture tion and develop- in t h e We s t e r n ment of culture in the C a p e We s t e r n C ape I n c re as ed u se of A ff o rdable facilities Accessibility to seven cul- 7,3% increase in number N o n e f ac i lit ies b y g ro u p s for all communities tural facilities of groups and 2,7% f rom previously dis- in t h e We s t e r n i n c rease in number of peo- advantaged commu- C a p e ple making use of facilities nities. -

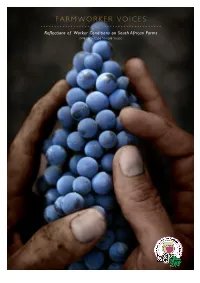

Bawsi-Report

CONTENTS 1. Introduction ............................. 3 32. Lindes Dam Farm ............................... 82 2. Farmworker Voices ......................... 6 33. Lombardye Farm ................................ 84 List of Farms ............................... 17 35. Merwida Cellars Farm ............................ 88 1. Anhohe Landgoed Farm/ Brakfontein . 18 36. Modderkloof Farm .............................. 90 2. Arbeidsvreugde Farm ............................ 20 37. Morester Grape And Olives Farm . 92 3. Avondrust Farm ................................ 22 38. Nuutgewek Farm ............................... 94 4. Bakenhof Farm ................................. 24 39. Ou Mure Farm ................................. 96 5. Brakfontein Trust Farm ........................... 26 40. Plaisir De Merle Farm ............................ 98 6. Dag En Nag Farm ............................... 28 41. Porseleinberg Farm ............................. 102 7. Dasdrif Farm ................................... 30 42. Roodehogte Diary Farm ......................... 104 8. De Hoek Farm .................................. 32 43. Rooi Draai Farm ............................... 106 9. De La Roche Farm .............................. 34 44. Ruiters Rest Farm .............................. 108 10. Die Denne Farm ................................ 36 45. Salem Farm ................................... 110 11. Diemerskraal Farm .............................. 38 46. Sanddrif Farm ................................. 112 12. Doorn Kraal Farm ............................. -

Kylemore Neighbourhood Watch, the Protectors Of

IN SEARCH OF ALTERNATIVE POLICING: KYLEMORE NEIGHBOURHOOD WATCH, THE PROTECTORS OF THEIR BELOVED COMMUNITY by CASSANDRA VISSER Thesis submitted in partial fl:l'HUIl) t of the requirements for the degree Master of Philosophy in Organisations and Public Cultures at the Department of Sociology and Social Anthropology Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences Supervisor: Prof CS van der Waal March 2009 CHAPTER 4: THE KYLEMORE SETTLEMENT AND ITS WESTERN CAPE CONTEXT 4.1 Introduction Thus far various theoretical perspectives on community, policing and policy have been discussed, but now it is time to place these theories in perspective, by situating them within the community of Kylemore. Before embarking on this matter, the location under study must first be introduced and contextualized, to ensure a better understanding of how and why certain events have played out. The aim of this chapter is therefore to contextualise the location and events under study and to situate Kylemore within the specific historical, socio economical and development context of the Dwars River Valley and the broader Western Cape. This I will attempt to achieve by not only focusing on Kylemore and its experiences, but also by providing an historical background to the lifestyle in the Westem Cape from before colonialisation until the present. I will focus predominantly on the presently so-called 'coloured' people within the Western Cape and their interaction with the colonialists and the missionaries. This interaction ultimately led to the adoption of Christianity and a sense of respectability, which are fundamental factors that emerge in this study that help to comprehend the notions of crime and policing within Kylemore. -

Babylons Fact Sheet.Indd

BABYLONSTOREN – at a glance … BABYLONSTOREN GUEST ACCOMMODATION Our guests return home from a stay at Babylonstoren more in tune · We welcome a maximum of just 32 guests with themselves and the world around them, with an understanding · 8 en-suite one bedroomed guest cottages and appreciation of a small piece of Cape farming history, beauty and · 4 en-suite two bedroomed guest cottages which are ideal for families hospitality and 4 guests travelling together · All the cottages have underfl oor heating and most have fi replaces WHAT MAKES BABYLONSTOREN SPECIAL … · All cottages have either a garden or vineyard view with an area for · A 240 hectare working wine and fruit farm that dates back over 300 alfresco dining years · For families or guests travelling in a small group, Babylonstoren’s historic · A place so beautiful, a welcome so warm and an experience so pure, Cape Dutch home, the fi ve-bedroomed Manor House is available on quite unlike any other in the historic Cape Winelands request only on an exclusive use basis. Please contact us for further · A quiet corner of the Cape that is surrounded by majestic sandstone details mountains on three sides where the fynbos is home to many wild creatures BABYLONSTOREN GUEST AREAS · Service that is both sincere and charming, and deeply proud of its · Babel, a Maranda Engelbrecht inspired restaurant, serves clean food with Afrikaner heritage distinct fl avours that celebrates the seasons and the bounty of the garden · A garden that quite simply will take your breath away · A welcome area that is perfect -

Thesis Ebe 2019 Ma Kiese Ste

Development of a Geographical Information System Based Transport Assessment Approach in Rural South Africa The Case of Healthcare Accessibility in Cape Winelands District Municipality Town Cape of University Dissertation presented in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Masters in Science, Civil Engineering Special field: Transport Studies, In the Department of Civil Engineering, EBE Faculty, University of Cape Town October 2019 By: Stephane Simon Masamba Ma-Kiese The copyright of this thesis vests inTown the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes Capeonly. of Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University Dedication This thesis is dedicated to the memory of my grandfather, Simon Masamba Makela. “Il est grand celui qui respecte le petit.” Development of a Geographical Information System Based Transport Assessment Approach in Rural South Africa The Case of Healthcare Accessibility in Cape Winelands District Municipality Dissertation presented in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Masters in Science, Civil Engineering Special field: Transport Studies Department of Civil Engineering, EBE Faculty, University of Cape Town Private Bag X3, Rondebosch, 7701 October 2019 By: Stephane Simon Masamba Ma-Kiese Declaration of Free License I Stephane Simon Masamba Ma-Kiese hereby: (a) grant the University free license to reproduce the above thesis in whole or in part, for the purpose of research; (b) declare that: (i) The research reported in this thesis, except otherwise indicated, is my original research. -

Proposed New Retreat, Portion 11 of Farm 1674 at Boschendal: Public Participation Plan

PROPOSED NEW RETREAT, PORTION 11 OF FARM 1674 AT BOSCHENDAL: PUBLIC PARTICIPATION PLAN RevisedProposed Public Participation Plan as Part of the Basic Assessment Process for the Proposed 10/6/2020 Development of a “New Retreat” on a portion of Portion 11 of Farm 1674, Paarl (NOI Ref: 16/3/3/6/7/1/B4/12/1086/20) Prepared by: Prepared for: Chand Environmental Consultants Boschendal (Pty) Ltd P.O Box 238, Plumstead, 7801 Helshoogte Road, Pniel Tel: 021 762 3060 www.boschendal.com Fax: 021 762 3240 www.chand.co.za Specialists in Environmental Management and Research Page 0 Contents 1. INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................... 2 2. ASSUMPTIONS AND LIMITATIONS ......................................................................................... 3 3. PROPOSED PRE-APPLICATION PUBLIC PARTICIPATION ACTIVITIES ..................................... 4 3.1 Identification of I&APs .............................................................................................................................. 4 3.2 Public Review of Pre-Application Draft Basic Assessment Report ................................................... 4 4 PROPOSED POST-APPLICATION PUBLIC PARTICIPATION ACTIVITIES .................................. 5 4.1 Public Review of Post-Application Draft Basic Assessment Report .................................................. 5 4.2 Notification of DEA&DP Decision .......................................................................................................... -

Profile: Cape Winelands

2 PROFILE: CAPE WINELANDS PROFILE: CAPE WINELANDS 3 CONTENT 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................ 5 2. BRIEF OVERVIEW ......................................................................................................... 7 2.1 Location .......................................................................................................................... 7 2.2 Historical perspective ...................................................................................................... 7 2.3 Spatial Status ................................................................................................................. 8 2.4 Land ownership ........................................................................................................... 10 3. SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT PROFILE ............................................................................ 11 3.1 Key Social Demographics ............................................................................................. 11 3.1.1 Population ............................................................................................................ 11 3.1.2 Race, Gender and Age ........................................................................................ 12 3.1.3 Households .......................................................................................................... 13 3.1.3.1 Child Headed .......................................................................................................... -

Western Cape Field Guides Association of South Africa, Bi

Western Cape Field Guides Association of South Africa, Bi-Annual Meeting 3rd August 2019 8:00 AM – 14:00 PM Groot Drakenstein Games Club R45, Simondium, Western Cape,7680 DRIVERS OF FYNBOS PROGRAMME Families welcome! 8:30 Tea and Coffee Come early for some tea, coffee, and enjoy the beautiful morning sun on the cricket grounds! 9:00 Welcome and introductions Mark Heistein Welcome and introductions Michelle Du Plessis Latest FGASA News 9:30 Patrick Shone Conservation Manager at Cape Nature Topic: Fires and its effects on fynbos and tourism within Cape Nature 10:15 Tea & P 10:30 Jenny Cullinan A bee conservationist and artist, she has joined us all the way from the karoo! Topic: Bee Conservation: The untold story 11:15 John Rogers Lecturer, researcher, and Geology enthusiast! Topic: Geology in the Fairest Cape His book GEOLOGICAL ADVENTURES IN THE FAIREST CAPE: UNLOCKING THE SECRETS OF ITS SCENERY will be available to buy for R 350.00. Cash only. 12:00 Certificates Graduates of the FGASA & Life Skills Course Michelle Du Plessis Summary of the Course Wendy Mhlauli 12:45 Lunch and mingle On the menu: Delicious Soup, traditional Whose footprints do you see? Poijke (vegetable and chicken), and a Photo taken at the back of the Berg River Dam, surprise pudding! Franschhoek SPEAKERS Patrick Shone Worked for Capenature for 23 years and been a Conservation Manager at Cape Nature since 2003 and ongoing. He specializes in Fire management and alien vegetation management in addition to his normal duties as a conservation/reserve manager. He enjoys the outdoors and has an interest in technology and the implementation there of in the environmental sector. -

Cape Winelands District Integrated Transport Plan 2016 -2021

Cape Winelands District Integrated Transport Plan 2016 -2021 May 2016 Document title: Cape Winelands District Integrated Transport Plan Status: Final Report Date: May 2016 Project name: Review of the District Integrated Transport Plan for the Cape Winelands Project number: T01.CPT.000287 Client: Cape Winelands District Municipality Client contact: Bevan Kurtz/ Chwayita Nkasela Reference: 16/2/2 Drafted by: Marco Steenkamp, Rory Williams, Gerard van Weele, Gregory Pryce-Lewis Checked by: Roy Bowman Date/initials check: Approved by: Bevan Kurtz Date/initials approval: Executive Summary Introduction This document constitutes the Integrated Transport Plan for the Cape Winelands District Municipality for the five year period from July 2016 to June 2021. This District Integrated Transport Plan (DITP) has been prepared in accordance with the requirements of the National Land Transport Act (NLTA) 2009, and as a designated Planning Authority it is the Cape Winelands District Municipality’s responsibility to administer this plan. The DITP contains the the district and local municipalities vision for transport, describes the existing roads and public transport infrastructure and operations, proposes a revised strategy for managing bus and taxi operating licences, discusses the transport needs of the district, and indicates the funding required to address the transport needs. Local Integrated Transport Plans (LITPs) have also been prepared for four local municipalities in the district, namely Breede Valley, Drakenstein, Langeberg and Witzenberg, as well as, although by a separate process, a Comprehensive Integrated Transport Plan for the Stellenbosch local municipality. The district and local municipalities’ Integrated Transport Plans have all been prepared in accordance with the Department of Transport guidelines and minimum requirements for the preparation of Integrated Transport Plans. -

Public Libraries

Phone: 021 483 2044/0718/2249 Fax: 021 419 7541 Helga Fraser (Research Librarian) E-mail: [email protected] Shanaaz Ebrahim (Library Assistant Research) E-mail: [email protected] WESTERN CAPE PUBLIC LIBRARY LIST June 2017 Abbotsdale Public Library (SWARTLAND MUNICIPALITY) c/o Swartland Municipality, Private Bag X52, Malmesbury, 7300 Roosmaryn Street, Abbotsdale, 7300 Contact: Brian Dirkse Tel: 022 487 9474 E-mail: [email protected] Latitude Longitude -33.496131 18.667829 Adriaanse Public Library (CITY OF CAPE TOWN MUNICIPALITY) PO Box 4725, Cape Town, 8000 Adriaanse Avenue, Elsies River, 7490 Contact: Barry Jagger Tel: 021 444 2392 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Latitude Longitude - 33.9375700003 18.5847500005 Albertinia Public Library (HESSEQUA MUNICIPALITY) 2 Horn Street, Albertinia, 6695 Contact: Ms Ursula Oosthuizen Tel: 0864015186(office) E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Latitude Longitude - 34.2028211908 21.5851326493 Algeria Mini Library (CEDERBERG MUNICIPALITY) Algeria settlement, halfway between Clanwilliam and Citrusdal PO Box 440, Clanwilliam, 8135 Contact: Ms E. Hanekom Cell: 076 559 2347 Tel: 027 482 1137 E-mail: [email protected] (Librarian) E-mail: [email protected] (Municiapal library manager) Latitude Longitude -32.373509 19.058529 Ashbury Public Library (LANGEBERG MUNICIPALITY) 52 Wilge Ave, Ashbury 1 Private Bag X2, Ashton, 6715 Cor Eike and Wilge Avenue, Ashbury, Montagu Contact: Ms -

Fresh Fruit Export Directory 2017

FRESH FRUIT EXPORT DIRECTORY 2017 www.fpef.co.za CLIENT: Vanguard ITEM: South Africa Fresh Fruit Export Directory Ad INSERTION DATE: 2017 CYAN MAGENTA YELLOW BLACK 604.988.1407 DOCKET: VAN-16-015 SIZE: 210mm x 148mm ARTWORK DUE: Nov. 21, 2016 CONTENTS ADVERTISERS 3 Message from the CEO inside front cover Vanguard International 4 Overview of South Africa 2 Lona 5 Overview of the FPEF 6 Vintage 7 List of FPEF members 36 FVC International 8 FPEF exporter members 64 Niche Fruit 38 FPEF associate members 78 Stargrow 44 Stone fruit statistics and information 88 SAFE 62 List of stone fruit exporters 100 Grown4U 65 Stone fruit associations’ information 104 Unlimited Group 66 Pome fruit statistics and information 106 Dole 76 List of pome fruit exporters 120 Capespan 79 Pome fruit associations’ information 122 PPECB 80 Table grape statistics and information 130 GoGlobal 86 List of table grape exporters 132 Cape Five 89 Table grape association’s information inside back cover Neopak 90 Citrus fruit statistics and information back cover Zest Fruit 102 List of citrus fruit exporters 107 Citrus fruit associations’ information 108 Subtropical fruit statistics and information 121 List of subtropical fruit exporters 123 Subtropical fruit associations’ information 124 Exotic fruit statistics and information 131 List of exotic fruit exporters 1 MESSAGE FROM THE CEO The South African Fresh Produce Exporters’ Forum (FPEF) is pleased to present Information regarding FPEF members is updated regularly on the FPEF website: the 2017 edition of the Fresh Fruit Export Directory. This directory is published www.fpef.co.za annually as a service to, and a source of information for the international fresh fruit trading community.