The Possible Effect of Steroids on Home Run Production

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NCAA Division I Baseball Records

Division I Baseball Records Individual Records .................................................................. 2 Individual Leaders .................................................................. 4 Annual Individual Champions .......................................... 14 Team Records ........................................................................... 22 Team Leaders ............................................................................ 24 Annual Team Champions .................................................... 32 All-Time Winningest Teams ................................................ 38 Collegiate Baseball Division I Final Polls ....................... 42 Baseball America Division I Final Polls ........................... 45 USA Today Baseball Weekly/ESPN/ American Baseball Coaches Association Division I Final Polls ............................................................ 46 National Collegiate Baseball Writers Association Division I Final Polls ............................................................ 48 Statistical Trends ...................................................................... 49 No-Hitters and Perfect Games by Year .......................... 50 2 NCAA BASEBALL DIVISION I RECORDS THROUGH 2011 Official NCAA Division I baseball records began Season Career with the 1957 season and are based on informa- 39—Jason Krizan, Dallas Baptist, 2011 (62 games) 346—Jeff Ledbetter, Florida St., 1979-82 (262 games) tion submitted to the NCAA statistics service by Career RUNS BATTED IN PER GAME institutions -

The Rules of Scoring

THE RULES OF SCORING 2011 OFFICIAL BASEBALL RULES WITH CHANGES FROM LITTLE LEAGUE BASEBALL’S “WHAT’S THE SCORE” PUBLICATION INTRODUCTION These “Rules of Scoring” are for the use of those managers and coaches who want to score a Juvenile or Minor League game or wish to know how to correctly score a play or a time at bat during a Juvenile or Minor League game. These “Rules of Scoring” address the recording of individual and team actions, runs batted in, base hits and determining their value, stolen bases and caught stealing, sacrifices, put outs and assists, when to charge or not charge a fielder with an error, wild pitches and passed balls, bases on balls and strikeouts, earned runs, and the winning and losing pitcher. Unlike the Official Baseball Rules used by professional baseball and many amateur leagues, the Little League Playing Rules do not address The Rules of Scoring. However, the Little League Rules of Scoring are similar to the scoring rules used in professional baseball found in Rule 10 of the Official Baseball Rules. Consequently, Rule 10 of the Official Baseball Rules is used as the basis for these Rules of Scoring. However, there are differences (e.g., when to charge or not charge a fielder with an error, runs batted in, winning and losing pitcher). These differences are based on Little League Baseball’s “What’s the Score” booklet. Those additional rules and those modified rules from the “What’s the Score” booklet are in italics. The “What’s the Score” booklet assigns the Official Scorer certain duties under Little League Regulation VI concerning pitching limits which have not implemented by the IAB (see Juvenile League Rule 12.08.08). -

Lessons You Can Learn by Watching a Game

Lessons You Can Learn by Watching a Game Good coaches no matter how old they are will watch a game and come away learning something. Even if they may be watching the game for enjoyment, there is always something they will see that could possibly help them in the future. A great teaching moment is to take your team to a game or watch a game on TV with them. Show your players during that game not only the good things that are happening but also the things that are done that may cost a run and eventually a game. Coaches can teach their players what to look for during the game like offensive and defensive weaknesses and tendencies. They can teach situations that come up during the game and can teach why something worked or why it didn’t work. Pictures are worth a thousand words. Even watching Major League Baseball games on TV will provide a lot of teachable moments. Lesson One: When Jason Wurth hit the winning walk off home run in the ninth inning during game four against the Cardinals, the Nationals went wild. Yes, it was a big game to win but it was not the Championship game. Watching them storm the field and jump up and down with excitement, made me shake my head. I have been on both sides of that scenario and that becomes bulletin board material. The Cardinals came back to win the next game and take the series. Side note: in case you have never heard that term, bulletin board material means that a player/team said or did something that could make the other team irritated at them to the point that it inspires that other team to do everything possible to beat the team. -

Here Comes the Strikeout

LEVEL 2.0 7573 HERE COMES THE STRIKEOUT BY LEONARD KESSLER In the spring the birds sing. The grass is green. Boys and girls run to play BASEBALL. Bobby plays baseball too. He can run the bases fast. He can slide. He can catch the ball. But he cannot hit the ball. He has never hit the ball. “Twenty times at bat and twenty strikeouts,” said Bobby. “I am in a bad slump.” “Next time try my good-luck bat,” said Willie. “Thank you,” said Bobby. “I hope it will help me get a hit.” “Boo, Bobby,” yelled the other team. “Easy out. Easy out. Here comes the strikeout.” “He can’t hit.” “Give him the fast ball.” Bobby stood at home plate and waited. The first pitch was a fast ball. “Strike one.” The next pitch was slow. Bobby swung hard, but he missed. “Strike two.” “Boo!” Strike him out!” “I will hit it this time,” said Bobby. He stepped out of the batter’s box. He tapped the lucky bat on the ground. He stepped back into the batter’s box. He waited for the pitch. It was fast ball right over the plate. Bobby swung. “STRIKE TRHEE! You are OUT!” The game was over. Bobby’s team had lost the game. “I did it again,” said Bobby. “Twenty –one time at bat. Twenty-one strikeouts. Take back your lucky bat, Willie. It was not lucky for me.” It was not a good day for Bobby. He had missed two fly balls. One dropped out of his glove. -

No No Runs Counted? No No 7 Run Per Inning Rule? No Yes 10 Run Rule (I.E

2017 5U & 6U Baseball Rules 5U 6U Game Target Number Of Innings 3 or 4 4 or 5 Time Limit 1Hr. 15 Min. 1Hr. 15 Min. Umpire? No No Runs Counted? No No 7 Run Per Inning Rule? No Yes 10 Run Rule (i.e. game over)? No No Wins/losses are not tracked. Outs and runs tracked for inning change reasons only. Teams change per half- Game/Inning Tracking inning based on whichever happens first, 3-outs, 7 runs Wins/losses and runs are not tracked, hit entire roster in an half-inning, or the team hits their roster 1X in that each inning half-inning. Official Ball 9 in. 5 oz. ball TL safety ball (ROTBP5) 9 in. 5 oz. ball TL safety ball (ROTBP5) Field Base Distance (feet) 40 40 Pitching Distance (feet) 10 to 15 10 to 20 Pitcher Coach - Underhanded Coach - Overhanded Coaches On Field 4 4 Fielders Total Fielders Unlimited 12 (remainder sit on bench) Infielders 5-6 (1B, 2B, 3B, SS & discretionary 2nd P or Short 2B) 6 (P, C, 1B, 2B, 3B & SS) Catcher Coach Player (Coach Assist) Max of 6 (Must be at least 30 feet into the outfield and Outfielders Unlimited not playing on the lip of the infield) Batting Helmets Required? Yes Yes Only hit full roster once per half-inning as long as 3-outs Batting Order? Roster (each inning) or 7-runs not reached first Outs Observed? No Yes (3 outs) Outs Per Inning N/A 3 Outs Pitch Limit Per Batter 6 (+2 via tee) 6 (+2 via tee) Max Runs per inning? Unlimited 7 Balls and Strikes Observed? No No No, if hitter does not make contact by pitch max, coach No, if hitter does not make contact by pitch max, coach Strike Outs Observed? should throw ground ball to simulate hit should throw ground ball to simulate hit Walks Observed? No No Bunting Allowed? No No Base Running Helmets Required? Yes Yes Bases Per Batted Ball 1 Unlimited (until touched by infielder) Lead Off Allowed Before Pitch? No No Lead Off Allowed After Pitch? No No Stealing Allowed? No No Sliding Allowed? No No Bases Per Overthrow to 1st Base/Any Base None None KEY GROUND RULES: Home Team supplies 2 game balls. -

Report of the Committee Studying Home Run Rates in Major League Baseball

Report of the Committee Studying Home Run Rates in Major League Baseball Jim Albert1, Jay Bartroff2, Roger Blandford3, Dan Brooks4, Josh Derenski2, Larry Goldstein2, Anette (Peko) Hosoi5, Gary Lorden6, Alan Nathan7, and Lloyd Smith8 1Bowling Green State University 2University of Southern California 3Stanford 4BrooksBaseball.net 5MIT 6Caltech 7University of Illinois 8Washington State May24, 2018 Abstract A report is given analyzing possible causes of the surge in home run rate in Major League Baseball in the past several years. 1 Executive Summary We, the members of the committee, were charged by the Office of the Commissioner of Baseball (BOC) to give the full benefit of our knowledge and expertise and to conduct primary and secondary research in order to identify the potential causes of the increase in the rate at which home runs were hit in 2015, 2016, and 2017. The committee reported directly to Morgan Sword (Senior Vice President, League Economics and Operations), who, along with Reed MacPhail (Senior Director, League Economics) and Roy Krasik (Senior Director, League Op- erations) were very supportive of our many requests for resources that were needed to carry out our charge. The committee set its own agenda and arrived at its own conclusions and recommendations, independent of MLB. Methodology In order to conduct our investigations, we performed the following analysis and testing: 1. We reviewed and analyzed StatCast statistical data from the 2015, 2016 and 2017 seasons, including data on pitch type, exit velocity, launch angle, spray angle, spin rate, spin axis, and distance traveled. We also reviewed and analyzed HITf/x statistical data from the 2015 and 2016 seasons, including data on exit velocity, launch angle, and spray angle. -

Guide to Softball Rules and Basics

Guide to Softball Rules and Basics History Softball was created by George Hancock in Chicago in 1887. The game originated as an indoor variation of baseball and was eventually converted to an outdoor game. The popularity of softball has grown considerably, both at the recreational and competitive levels. In fact, not only is women’s fast pitch softball a popular high school and college sport, it was recognized as an Olympic sport in 1996. Object of the Game To score more runs than the opposing team. The team with the most runs at the end of the game wins. Offense & Defense The primary objective of the offense is to score runs and avoid outs. The primary objective of the defense is to prevent runs and create outs. Offensive strategy A run is scored every time a base runner touches all four bases, in the sequence of 1st, 2nd, 3rd, and home. To score a run, a batter must hit the ball into play and then run to circle the bases, counterclockwise. On offense, each time a player is at-bat, she attempts to get on base via hit or walk. A hit occurs when she hits the ball into the field of play and reaches 1st base before the defense throws the ball to the base, or gets an extra base (2nd, 3rd, or home) before being tagged out. A walk occurs when the pitcher throws four balls. It is rare that a hitter can round all the bases during her own at-bat; therefore, her strategy is often to get “on base” and advance during the next at-bat. -

Baseball/Softball

SAMPLE SITUTATIONS Situation Enter for batter Enter for runner Hit (single, double, triple, home run) 1B or 2B or 3B or HR Hit to location (LF, CF, etc.) 3B 9 or 2B RC or 1B 6 Bunt single 1B BU Walk, intentional walk or hit by pitch BB or IBB or HP Ground out or unassisted ground out 63 or 43 or 3UA Fly out, pop out, line out 9 or F9 or P4 or L6 Pop out (bunt) P4 BU Line out with assist to another player L6 A1 Foul out FF9 or PF2 Foul out (bunt) FF2 BU or PF2 BU Strikeouts (swinging or looking) KS or KL Strikeout, Fouled bunt attempt on third strike K BU Reaching on an error E5 Fielder’s choice FC 4 46 Double play 643 GDP X Double play (on strikeout) KS/L 24 DP X Double play (batter reaches 1B on FC) FC 554 GDP X Double play (on lineout) L63 DP X Triple play 543 TP X (for two runners) Sacrifi ce fl y F9 SF RBI + Sacrifi ce bunt 53 SAC BU + Sacrifi ce bunt (error on otherwise successful attempt) E2T SAC BU + Sacrifi ce bunt (no error, lead runner beats throw to base) FC 5 SAC BU + Sacrifi ce bunt (lead runner out attempting addtional base) FC 5 SAC BU + 35 Fielder’s choice bunt (one on, lead runner out) FC 5 BU (no sacrifi ce) 56 Fielder’s choice bunt (two on, lead runner out) FC 5 BU (no sacrifi ce) 5U (for lead runner), + (other runner) Catcher or batter interference CI or BI Runner interference (hit by batted ball) 1B 4U INT (awarded to closest fi elder)* Dropped foul ball E9 DF Muff ed throw from SS by 1B E3 A6 Batter advances on throw (runner out at home) 1B + T + 72 Stolen base SB Stolen base and advance on error SB E2 Caught stealing -

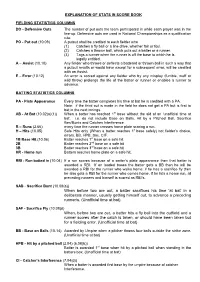

How to Do Stats

EXPLANATION OF STATS IN SCORE BOOK FIELDING STATISTICS COLUMNS DO - Defensive Outs The number of put outs the team participated in while each player was in the line-up. Defensive outs are used in National Championships as a qualification rule. PO - Put out (10.09) A putout shall be credited to each fielder who (1) Catches a fly ball or a line drive, whether fair or foul. (2) Catches a thrown ball, which puts out a batter or a runner. (3) Tags a runner when the runner is off the base to which he is legally entitled. A – Assist (10.10) Any fielder who throws or deflects a battered or thrown ball in such a way that a putout results or would have except for a subsequent error, will be credited with an Assist. E – Error (10.12) An error is scored against any fielder who by any misplay (fumble, muff or wild throw) prolongs the life of the batter or runner or enables a runner to advance. BATTING STATISTICS COLUMNS PA - Plate Appearance Every time the batter completes his time at bat he is credited with a PA. Note: if the third out is made in the field he does not get a PA but is first to bat in the next innings. AB - At Bat (10.02(a)(1)) When a batter has reached 1st base without the aid of an ‘unofficial time at bat’. i.e. do not include Base on Balls, Hit by a Pitched Ball, Sacrifice flies/Bunts and Catches Interference. R – Runs (2.66) every time the runner crosses home plate scoring a run. -

It's a Hit! the Mathematics in Baseball Student Edition

Copyright © 2014 by the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics, Inc. www.nctm.org. All rights reserved. For personal use only. Student It’s a Hit! Explorations in Mathematics It’s a Hit! The“ Mathematics in Baseball “It ain’t over ’til it’s over.” Yogi Berra “Baseball is the only field of endeavor where a man can succeed three times out of ten and be considered a good performer.” Ted Williams Baseball is a game of senses: The crack of the bat, the roar of the crowd, rubbing the dirt on your hands, the intensity in the pitcher’s eyes . You can also use your mathematical sense in the game. You can calculate the stolen base percentage against a given catcher or the on-base percentage plus slugging percentage for any given player. These statistics are easy to fi nd because Major League Baseball offi cially publishes 28 different batting statistics, 42 different pitching statistics, and 15 different fi elding statistics. In this activity, you will be looking into statistics that might Work your way through this series of questions and see not be available on mlb.com or other baseball sites. how math is used to calculate a wide variety of baseball statistics. 1. Aside from the players and the plays, identify other information you want to know about the game of Some people date baseball to the 1700s, but it became baseball. popular when its rules were codifi ed soon after the Civil War. During the many years that the game has been played, the ball itself has undergone numerous changes. -

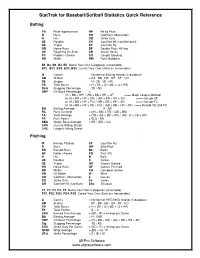

Stattrak for Baseball/Softball Statistics Quick Reference

StatTrak for Baseball/Softball Statistics Quick Reference Batting PA Plate Appearances HP Hit by Pitch R Runs CO Catcher's Obstruction H Hits SO Strike Outs 2B Doubles SH Sacrifice Hit (sacrifice bunt) 3B Triples SF Sacrifice Fly HR Home Runs DP Double Plays Hit Into OE Reaching On-Error SB Stolen Bases FC Fielder’s Choice CS Caught Stealing BB Walks RBI Runs Batted In B1, B2, B3, B4, B5 Name Your Own Categories (renamable) BS1, BS2, BS3, BS4, BS5 Create Your Own Statistics (renamable) G Games = Number of Batting records in database AB At Bats = PA - BB - HP - SH - SF - CO 1B Singles = H - 2B - 3B - HR TB Total Bases = H + 2B + (2 x 3B) + (3 x HR) SLG Slugging Percentage = TB / AB OBP On-Base Percentage = (H + BB + HP) / (AB + BB + HP + SF) <=== Major League Method or (H + BB + HP + OE) / (AB + BB + HP + SF) <=== Include OE or (H + BB + HP + FC) / (AB + BB + HP + SF) <=== Include FC or (H + BB + HP + OE + FC) / (AB + BB + HP + SF) <=== Include OE and FC BA Batting Average = H / AB RC Runs Created = ((H + BB) x TB) / (AB + BB) TA Total Average = (TB + SB + BB + HP) / (AB - H + CS + DP) PP Pure Power = SLG - BA SBA Stolen Base Average = SB / (SB + CS) CHS Current Hitting Streak LHS Longest Hitting Streak Pitching IP Innings Pitched SF Sacrifice Fly R Runs WP Wild Pitch ER Earned-Runs Bk Balks BF Batters Faced PO Pick Offs H Hits B Balls 2B Doubles S Strikes 3B Triples GS Games Started HR Home Runs GF Games Finished BB Walks CG Complete Games HB Hit Batter W Wins CO Catcher's Obstruction L Losses SO Strike Outs Sv Saves SH Sacrifice Hit -

![The Mental Game of Hitting [ARTICLE]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3112/the-mental-game-of-hitting-article-1613112.webp)

The Mental Game of Hitting [ARTICLE]

The Mental Game of Hitting [ARTICLE] http://softball.coachesdirectory.com/article/the-mental-game-of-hitting-article.html Hitting Articles The Mental Game of Hitting excerpt from the book Softball Skills & Drills-2nd Edition by Judi Garman, Michelle Gromacki Hitting is adjusting–adjusting to the pitch, the type of pitcher, the count, the umpire, and the situation. The mental game of hitting begins in practice. In a game, it begins on the bench, continues in the on-deck circle and on the approach to the plate, and reaches its greatest intensity when the batter steps into the batter's box. Batters must be in control of themselves before they can control their at-bat. Self-control leads to body and skill control. Success requires discipline, concentration, and quickness. Hitters should focus on one pitch at a time and on the process of the at-bat–not the result. They learn from every swing as they obtain immediate feedback and make the adjustments necessary for success. Instead of making excuses on a missed opportunity, good hitters figure out what they learned from the situation (too late, too fast, under the ball, and so on) and make mental notes on how to use that knowledge to succeed the next time. They also take note of what they were doing well when successful. Hitting is an attitude. It is confidence. Players should believe that they are al-ways going to hit the ball solidly "on the money!" Focus on the number of "quality at-bats" and not the batting average (because a hitter may hit the ball well but at someone).