It's a Hit! the Mathematics in Baseball Student Edition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Preview

DETROIT TIGERS’ 4 GREATEST HITTERS Table of CONTENTS Contents Warm-Up, with a Side of Dedications ....................................................... 1 The Ty Cobb Birthplace Pilgrimage ......................................................... 9 1 Out of the Blocks—Into the Bleachers .............................................. 19 2 Quadruple Crown—Four’s Company, Five’s a Multitude ..................... 29 [Gates] Brown vs. Hot Dog .......................................................................................... 30 Prince Fielder Fields Macho Nacho ............................................................................. 30 Dangerfield Dangers .................................................................................................... 31 #1 Latino Hitters, Bar None ........................................................................................ 32 3 Hitting Prof Ted Williams, and the MACHO-METER ......................... 39 The MACHO-METER ..................................................................... 40 4 Miguel Cabrera, Knothole Kids, and the World’s Prettiest Girls ........... 47 Ty Cobb and the Presidential Passing Lane ................................................................. 49 The First Hammerin’ Hank—The Bronx’s Hank Greenberg ..................................... 50 Baseball and Heightism ............................................................................................... 53 One Amazing Baseball Record That Will Never Be Broken ...................................... -

November 16, 2012

November 16, 2012 Page 1 of 38 Clips (November 16, 2012) November 16, 2012 Page 2 of 38 Today’s Clips Contents From the Los Angeles Times (Page 3) Mike Trout robbed? No, Miguel Cabrera deserved MVP award From the Orange County Register (Page 4) AL MVP award is one thing Trout can't quite catch How the Angels may have saved a lot of money today From ESPN.com (Page 7) Cabrera wins on narrative, not numbers Miguel Cabrera named AL MVP From Angels.com (Page 10) Trout finishes second in AL MVP tally Hunter deal right move for Tigers ... and Angels Salmon: Maturation key to Trout's future success From Fox Sports West (Page 17) AL MVP debate got unnecessarily rude From SportsIllustrated.com (Page 19) Cabrera wins AL MVP but debate rages on -- and that's good Cabrera's win over Trout for AL MVP proves team results matter From Yahoo Sports (Page 25) Culture war over Miguel Cabrera's MVP award win over Mike Trout showed beauty of baseball From USA Today (Page 27) Triple Crown winner Cabrera edges Trout for AL MVP Trout deserved better in MVP voting From the Vineland Daily Journal (Page 31) Trout learning to deal with new-found stardom Trout takes 2nd in MVP race From the Wall Street Journal (Page 35) Does the RBI Mean Anything? From the Boston Globe (Page 36) The Holy War of the BBWAA November 16, 2012 Page 3 of 38 FROM THE LOS ANGELES TIMES Mike Trout robbed? No, Miguel Cabrera deserved MVP award By Houston Mitchell 9:14 AM PST, November 16, 2012 Many Angels fans are up in arms today over the fact that Detroit's Miguel Cabrera won the AL MVP award over Angels center fielder Mike Trout, who finished a distant second. -

Baseball Classics All-Time All-Star Greats Game Team Roster

BASEBALL CLASSICS® ALL-TIME ALL-STAR GREATS GAME TEAM ROSTER Baseball Classics has carefully analyzed and selected the top 400 Major League Baseball players voted to the All-Star team since it's inception in 1933. Incredibly, a total of 20 Cy Young or MVP winners were not voted to the All-Star team, but Baseball Classics included them in this amazing set for you to play. This rare collection of hand-selected superstars player cards are from the finest All-Star season to battle head-to-head across eras featuring 249 position players and 151 pitchers spanning 1933 to 2018! Enjoy endless hours of next generation MLB board game play managing these legendary ballplayers with color-coded player ratings based on years of time-tested algorithms to ensure they perform as they did in their careers. Enjoy Fast, Easy, & Statistically Accurate Baseball Classics next generation game play! Top 400 MLB All-Time All-Star Greats 1933 to present! Season/Team Player Season/Team Player Season/Team Player Season/Team Player 1933 Cincinnati Reds Chick Hafey 1942 St. Louis Cardinals Mort Cooper 1957 Milwaukee Braves Warren Spahn 1969 New York Mets Cleon Jones 1933 New York Giants Carl Hubbell 1942 St. Louis Cardinals Enos Slaughter 1957 Washington Senators Roy Sievers 1969 Oakland Athletics Reggie Jackson 1933 New York Yankees Babe Ruth 1943 New York Yankees Spud Chandler 1958 Boston Red Sox Jackie Jensen 1969 Pittsburgh Pirates Matty Alou 1933 New York Yankees Tony Lazzeri 1944 Boston Red Sox Bobby Doerr 1958 Chicago Cubs Ernie Banks 1969 San Francisco Giants Willie McCovey 1933 Philadelphia Athletics Jimmie Foxx 1944 St. -

Lessons You Can Learn by Watching a Game

Lessons You Can Learn by Watching a Game Good coaches no matter how old they are will watch a game and come away learning something. Even if they may be watching the game for enjoyment, there is always something they will see that could possibly help them in the future. A great teaching moment is to take your team to a game or watch a game on TV with them. Show your players during that game not only the good things that are happening but also the things that are done that may cost a run and eventually a game. Coaches can teach their players what to look for during the game like offensive and defensive weaknesses and tendencies. They can teach situations that come up during the game and can teach why something worked or why it didn’t work. Pictures are worth a thousand words. Even watching Major League Baseball games on TV will provide a lot of teachable moments. Lesson One: When Jason Wurth hit the winning walk off home run in the ninth inning during game four against the Cardinals, the Nationals went wild. Yes, it was a big game to win but it was not the Championship game. Watching them storm the field and jump up and down with excitement, made me shake my head. I have been on both sides of that scenario and that becomes bulletin board material. The Cardinals came back to win the next game and take the series. Side note: in case you have never heard that term, bulletin board material means that a player/team said or did something that could make the other team irritated at them to the point that it inspires that other team to do everything possible to beat the team. -

Here Comes the Strikeout

LEVEL 2.0 7573 HERE COMES THE STRIKEOUT BY LEONARD KESSLER In the spring the birds sing. The grass is green. Boys and girls run to play BASEBALL. Bobby plays baseball too. He can run the bases fast. He can slide. He can catch the ball. But he cannot hit the ball. He has never hit the ball. “Twenty times at bat and twenty strikeouts,” said Bobby. “I am in a bad slump.” “Next time try my good-luck bat,” said Willie. “Thank you,” said Bobby. “I hope it will help me get a hit.” “Boo, Bobby,” yelled the other team. “Easy out. Easy out. Here comes the strikeout.” “He can’t hit.” “Give him the fast ball.” Bobby stood at home plate and waited. The first pitch was a fast ball. “Strike one.” The next pitch was slow. Bobby swung hard, but he missed. “Strike two.” “Boo!” Strike him out!” “I will hit it this time,” said Bobby. He stepped out of the batter’s box. He tapped the lucky bat on the ground. He stepped back into the batter’s box. He waited for the pitch. It was fast ball right over the plate. Bobby swung. “STRIKE TRHEE! You are OUT!” The game was over. Bobby’s team had lost the game. “I did it again,” said Bobby. “Twenty –one time at bat. Twenty-one strikeouts. Take back your lucky bat, Willie. It was not lucky for me.” It was not a good day for Bobby. He had missed two fly balls. One dropped out of his glove. -

2019 Topps Luminaries Baseball Checklist

AUTOGRAPH HOME RUN KINGS HRK-AB Adrian Beltre Texas Rangers® HRK-AJ Aaron Judge New York Yankees® HRK-AJU Aaron Judge New York Yankees® HRK-AK Al Kaline Detroit Tigers® HRK-AM Andrew McCutchen Philadelphia Phillies® HRK-AR Alex Rodriguez Seattle Mariners™ HRK-ARI Anthony Rizzo Chicago Cubs® HRK-ARZ Anthony Rizzo Chicago Cubs® HRK-BJ B Jackson Kansas City Royals® HRK-BP Buster Posey San Francisco Giants® HRK-BW Bernie Williams New York Yankees® HRK-BWI Bernie Williams New York Yankees® HRK-CF Carlton Fisk Boston Red Sox® HRK-CJ Chipper Jones Atlanta Braves™ HRK-CJO Chipper Jones Atlanta Braves™ HRK-CR Cal Ripken Jr. Baltimore Orioles® HRK-CY Christian Yelich Milwaukee Brewers™ HRK-DM Don Mattingly New York Yankees® HRK-DMA Don Mattingly New York Yankees® HRK-DMU Dale Murphy Atlanta Braves™ HRK-DO David Ortiz Boston Red Sox® HRK-DOR David Ortiz Minnesota Twins® HRK-EJ Eloy Jimenez Chicago White Sox® Rookie HRK-FF Freddie Freeman Atlanta Braves™ HRK-FL Francisco Lindor Cleveland Indians® HRK-FLI Francisco Lindor Cleveland Indians® HRK-FT Frank Thomas Chicago White Sox® HRK-FTA Fernando Tatis Jr. San Diego Padres™ Rookie HRK-FTH Frank Thomas Chicago White Sox® HRK-FTJ Fernando Tatis Jr. San Diego Padres™ Rookie HRK-HA Hank Aaron Atlanta Braves™ HRK-HM Hideki Matsui New York Yankees® HRK-HMA Hideki Matsui Angels® HRK-I Ichiro Seattle Mariners™ HRK-IR Ivan Rodriguez Texas Rangers® HRK-JB Johnny Bench Cincinnati Reds® HRK-JBA Jeff Bagwell Houston Astros® HRK-JBG Jeff Bagwell Houston Astros® HRK-JP Jorge Posada New York Yankees® HRK-JPO Jorge Posada New York Yankees® HRK-JS Juan Soto Washington Nationals® HRK-JSO Juan Soto Washington Nationals® HRK-JT Jim Thome Cleveland Indians® HRK-JV Joey Votto Cincinnati Reds® HRK-KB Kris Bryant Chicago Cubs® HRK-KGJ Ken Griffey Jr. -

Comparing Hall of Fame Baseball Players Using Most Valuable Player Ranks Paul Kvam University of Richmond, [email protected]

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Math and Computer Science Faculty Publications Math and Computer Science 7-2011 Comparing Hall of Fame Baseball Players Using Most Valuable Player Ranks Paul Kvam University of Richmond, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/mathcs-faculty-publications Part of the Applied Statistics Commons Recommended Citation Kvam, Paul H. "Comparing Hall of Fame Baseball Players Using Most Valuable Player Ranks." Journal of Quantitative Analysis in Sports 7, no. 3 (July 2011): Article 19, 1-20. doi:10.2202/1559-0410.1337. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Math and Computer Science at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Math and Computer Science Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Journal of Quantitative Analysis in Sports Volume 7, Issue 3 2011 Article 19 Comparing Hall of Fame Baseball Players Using Most Valuable Player Ranks Paul H. Kvam, Georgia Institute of Technololgy Recommended Citation: Kvam, Paul H. (2011) "Comparing Hall of Fame Baseball Players Using Most Valuable Player Ranks," Journal of Quantitative Analysis in Sports: Vol. 7: Iss. 3, Article 19. DOI: 10.2202/1559-0410.1337 ©2011 American Statistical Association. All rights reserved. Comparing Hall of Fame Baseball Players Using Most Valuable Player Ranks Paul H. Kvam Abstract We propose a rank-based statistical procedure for comparing performances of top major league baseball players who performed in different eras. The model is based on using the player ranks from voting results for the most valuable player awards in the American and National Leagues. -

No No Runs Counted? No No 7 Run Per Inning Rule? No Yes 10 Run Rule (I.E

2017 5U & 6U Baseball Rules 5U 6U Game Target Number Of Innings 3 or 4 4 or 5 Time Limit 1Hr. 15 Min. 1Hr. 15 Min. Umpire? No No Runs Counted? No No 7 Run Per Inning Rule? No Yes 10 Run Rule (i.e. game over)? No No Wins/losses are not tracked. Outs and runs tracked for inning change reasons only. Teams change per half- Game/Inning Tracking inning based on whichever happens first, 3-outs, 7 runs Wins/losses and runs are not tracked, hit entire roster in an half-inning, or the team hits their roster 1X in that each inning half-inning. Official Ball 9 in. 5 oz. ball TL safety ball (ROTBP5) 9 in. 5 oz. ball TL safety ball (ROTBP5) Field Base Distance (feet) 40 40 Pitching Distance (feet) 10 to 15 10 to 20 Pitcher Coach - Underhanded Coach - Overhanded Coaches On Field 4 4 Fielders Total Fielders Unlimited 12 (remainder sit on bench) Infielders 5-6 (1B, 2B, 3B, SS & discretionary 2nd P or Short 2B) 6 (P, C, 1B, 2B, 3B & SS) Catcher Coach Player (Coach Assist) Max of 6 (Must be at least 30 feet into the outfield and Outfielders Unlimited not playing on the lip of the infield) Batting Helmets Required? Yes Yes Only hit full roster once per half-inning as long as 3-outs Batting Order? Roster (each inning) or 7-runs not reached first Outs Observed? No Yes (3 outs) Outs Per Inning N/A 3 Outs Pitch Limit Per Batter 6 (+2 via tee) 6 (+2 via tee) Max Runs per inning? Unlimited 7 Balls and Strikes Observed? No No No, if hitter does not make contact by pitch max, coach No, if hitter does not make contact by pitch max, coach Strike Outs Observed? should throw ground ball to simulate hit should throw ground ball to simulate hit Walks Observed? No No Bunting Allowed? No No Base Running Helmets Required? Yes Yes Bases Per Batted Ball 1 Unlimited (until touched by infielder) Lead Off Allowed Before Pitch? No No Lead Off Allowed After Pitch? No No Stealing Allowed? No No Sliding Allowed? No No Bases Per Overthrow to 1st Base/Any Base None None KEY GROUND RULES: Home Team supplies 2 game balls. -

Guide to Softball Rules and Basics

Guide to Softball Rules and Basics History Softball was created by George Hancock in Chicago in 1887. The game originated as an indoor variation of baseball and was eventually converted to an outdoor game. The popularity of softball has grown considerably, both at the recreational and competitive levels. In fact, not only is women’s fast pitch softball a popular high school and college sport, it was recognized as an Olympic sport in 1996. Object of the Game To score more runs than the opposing team. The team with the most runs at the end of the game wins. Offense & Defense The primary objective of the offense is to score runs and avoid outs. The primary objective of the defense is to prevent runs and create outs. Offensive strategy A run is scored every time a base runner touches all four bases, in the sequence of 1st, 2nd, 3rd, and home. To score a run, a batter must hit the ball into play and then run to circle the bases, counterclockwise. On offense, each time a player is at-bat, she attempts to get on base via hit or walk. A hit occurs when she hits the ball into the field of play and reaches 1st base before the defense throws the ball to the base, or gets an extra base (2nd, 3rd, or home) before being tagged out. A walk occurs when the pitcher throws four balls. It is rare that a hitter can round all the bases during her own at-bat; therefore, her strategy is often to get “on base” and advance during the next at-bat. -

Baseball: a U.S. Sport with a Spanish- American Stamp

ISSN 2373–874X (online) 017-01/2016EN Baseball: a U.S. Sport with a Spanish- American Stamp Orlando Alba 1 Topic: Spanish language and participation of Spanish-American players in Major League Baseball. Summary: The purpose of this paper is to highlight the importance of the Spanish language and the remarkable contribution to Major League Baseball by Spanish- American players. Keywords: baseball, sports, Major League Baseball, Spanish, Latinos Introduction The purpose of this paper is to highlight the remarkable contribution made to Major League Baseball (MLB) by players from Spanish America both in terms of © Orlando Alba Baseball: a U.S. Sport with a Spanish-American Stamp Informes del Observatorio / Observatorio Reports. 017-01/2016EN ISSN: 2373-874X (online) doi: 10.15427/OR017-01/2016EN Instituto Cervantes at FAS - Harvard University © Instituto Cervantes at the Faculty of Arts and Sciences of Harvard University quantity and quality.1 The central idea is that the significant and valuable Spanish-American presence in the sports arena has a very positive impact on the collective psyche of the immigrant community to which these athletes belong. Moreover, this impact extends beyond the limited context of sport since, in addition to the obvious economic benefits for many families, it enhances the image of the Spanish-speaking community in the United States. At the level of language, contact allows English to influence Spanish, especially in the area of vocabulary, which Spanish assimilates and adapts according to its own peculiar structures. Baseball, which was invented in the United States during the first half of the nineteenth century, was introduced into Spanish America about thirty or forty years later. -

Baseball/Softball

SAMPLE SITUTATIONS Situation Enter for batter Enter for runner Hit (single, double, triple, home run) 1B or 2B or 3B or HR Hit to location (LF, CF, etc.) 3B 9 or 2B RC or 1B 6 Bunt single 1B BU Walk, intentional walk or hit by pitch BB or IBB or HP Ground out or unassisted ground out 63 or 43 or 3UA Fly out, pop out, line out 9 or F9 or P4 or L6 Pop out (bunt) P4 BU Line out with assist to another player L6 A1 Foul out FF9 or PF2 Foul out (bunt) FF2 BU or PF2 BU Strikeouts (swinging or looking) KS or KL Strikeout, Fouled bunt attempt on third strike K BU Reaching on an error E5 Fielder’s choice FC 4 46 Double play 643 GDP X Double play (on strikeout) KS/L 24 DP X Double play (batter reaches 1B on FC) FC 554 GDP X Double play (on lineout) L63 DP X Triple play 543 TP X (for two runners) Sacrifi ce fl y F9 SF RBI + Sacrifi ce bunt 53 SAC BU + Sacrifi ce bunt (error on otherwise successful attempt) E2T SAC BU + Sacrifi ce bunt (no error, lead runner beats throw to base) FC 5 SAC BU + Sacrifi ce bunt (lead runner out attempting addtional base) FC 5 SAC BU + 35 Fielder’s choice bunt (one on, lead runner out) FC 5 BU (no sacrifi ce) 56 Fielder’s choice bunt (two on, lead runner out) FC 5 BU (no sacrifi ce) 5U (for lead runner), + (other runner) Catcher or batter interference CI or BI Runner interference (hit by batted ball) 1B 4U INT (awarded to closest fi elder)* Dropped foul ball E9 DF Muff ed throw from SS by 1B E3 A6 Batter advances on throw (runner out at home) 1B + T + 72 Stolen base SB Stolen base and advance on error SB E2 Caught stealing -

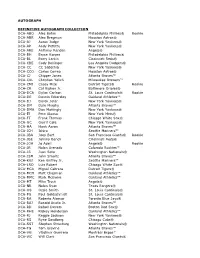

2021 Topps Definitive Collection BB Checklist.Xls

AUTOGRAPH DEFINITIVE AUTOGRAPH COLLECTION DCA-ABO Alec Bohm Philadelphia Phillies® Rookie DCA-ABR Alex Bregman Houston Astros® DCA-AJ Aaron Judge New York Yankees® DCA-AP Andy Pettitte New York Yankees® DCA-ARE Anthony Rendon Angels® DCA-BH Bryce Harper Philadelphia Phillies® DCA-BL Barry Larkin Cincinnati Reds® DCA-CBE Cody Bellinger Los Angeles Dodgers® DCA-CC CC Sabathia New York Yankees® DCA-CCO Carlos Correa Houston Astros® DCA-CJ Chipper Jones Atlanta Braves™ DCA-CKL Christian Yelich Milwaukee Brewers™ DCA-CMI Casey Mize Detroit Tigers® Rookie DCA-CR Cal Ripken Jr. Baltimore Orioles® DCA-DCA Dylan Carlson St. Louis Cardinals® Rookie DCA-DE Dennis Eckersley Oakland Athletics™ DCA-DJ Derek Jeter New York Yankees® DCA-DM Dale Murphy Atlanta Braves™ DCA-DMA Don Mattingly New York Yankees® DCA-EJ Pete Alonso New York Mets® DCA-FT Frank Thomas Chicago White Sox® DCA-GC Gerrit Cole New York Yankees® DCA-HA Hank Aaron Atlanta Braves™ DCA-ICH Ichiro Seattle Mariners™ DCA-JBA Joey Bart San Francisco Giants® Rookie DCA-JBE Johnny Bench Cincinnati Reds® DCA-JOA Jo Adell Angels® Rookie DCA-JR Nolan Arenado Colorado Rockies™ DCA-JS Juan Soto Washington Nationals® DCA-JSM John Smoltz Atlanta Braves™ DCA-KGJ Ken Griffey Jr. Seattle Mariners™ DCA-LRO Luis Robert Chicago White Sox® DCA-MCA Miguel Cabrera Detroit Tigers® DCA-MCH Matt Chapman Oakland Athletics™ DCA-MMC Mark McGwire Oakland Athletics™ DCA-MT Mike Trout Angels® DCA-NR Nolan Ryan Texas Rangers® DCA-OS Ozzie Smith St. Louis Cardinals® DCA-PG Paul Goldschmidt St. Louis Cardinals® DCA-RA Roberto Alomar Toronto Blue Jays® DCA-RAJ Ronald Acuña Jr.