Baseball: a U.S. Sport with a Spanish- American Stamp

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A's News Clips, Thursday, March 3, 2011 A's Outfielder Coco Crisp

A’s News Clips, Thursday, March 3, 2011 A's outfielder Coco Crisp arrested on suspicion of DUI By Joe Stiglich Oakland Tribune A's center fielder Coco Crisp was arrested on suspicion of driving under the influence of alcohol early Wednesday morning, according to an A's news release. Crisp was detained and taken to City of Scottsdale Jail before being released Wednesday morning. He showed up to Phoenix Municipal Stadium on time to join the team for pre-game drills and was in uniform -- but not in the lineup -- for a game against the Cleveland Indians. Crisp declined to comment when asked about the situation, saying he would address the media "in due time." "The A's are aware of the situation and take such matters seriously," the A's statement read. "The team and Coco will have no further comment until further details are available." Crisp, 31, is in his second season with the A's and is slated to play center field and be the leadoff hitter. Ironically, the A's held a security meeting with Major League Baseball officials before taking the field Wednesday. A message that is stressed in the annual meeting is having awareness of the off-field dangers that exist for professional athletes. Crisp signed with the A's as a free agent in December 2009. He hit .279 with eight homers and 38 RBIs last season but played in just 75 games because of a fractured pinkie and strained rib cage muscle. Crisp posts frequently on his Twitter account and often makes reference to his nighttime socializing. -

Baseball Rule” Faces an Interesting Test

The “Baseball Rule” Faces an Interesting Test One of the many beauties of baseball, affectionately known as “America’s pastime,” is the ability for people to come to the stadium and become ingrained in the action and get the chance to interact with their heroes. Going to a baseball game, as opposed to going to most other sporting events, truly gives a fan the opportunity to take part in the action. However, this can come at a steep price as foul balls enter the stands at alarming speeds and occasionally strike spectators. According to a recent study, approximately 1,750 people get hurt each year by batted 1 balls at Major League Baseball (MLB) games, which adds up to twice every three games. The 2015 MLB season featured many serious incidents that shed light on the issue of 2 spectator protection. This has led to heated debates among the media, fans, and even players and 3 managers as to what should be done to combat this issue. Currently, there is a pending class action lawsuit against Major League Baseball (“MLB”). The lawsuit claims that MLB has not 1 David Glovin, Baseball Caught Looking as Fouls Injure 1,750 Fans a Year, BLOOMBERG BUSINESS (Sept. 9, 2014, 4:05 PM), http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/20140909/baseballcaughtlookingasfoulsinjure1750fansayear. 2 On June 5, a woman attending a Boston Red Sox game was struck in the head by a broken bat that flew into the seats along the third baseline. See Woman hurt by bat at Red Sox game released from hospital, NEW YORK POST (June 12, 2015, 9:32 PM), http://nypost.com/2015/06/12/womanhurtbybatatredsoxgamereleasedfromhospital/. -

Baseball from Below: How America’S Pastime Became a Hemispheric Cultural Phenomenon

BASEBALL FROM BELOW: HOW AMERICA’S PASTIME BECAME A HEMISPHERIC CULTURAL PHENOMENON by Michael Warren Gallemore A thesis submitted to the faculty of The University of North Carolina at Charlotte in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Latin American Studies Charlotte 2015 Approved by: _____________________________ Dr. Gregory Weeks _____________________________ Dr. Jurgen Buchenau _____________________________ Dr. Benny Andres ii ©2015 Michael Warren Gallemore ALL RIGHTS RESERVED iii ABSTRACT MICHAEL WARREN GALLEMORE Baseball from below: how America’s pastime became a hemispheric cultural phenomenon (Under the direction of DR. GREG WEEKS) The game of baseball has rarely changed since its beginnings, and its resultant ascent to the United States national pastime has done little to change the fundamentals of the sport. However, there have been significant shifts in the demographics of Major League Baseball. Latino players have seen their numbers jump up to 26.9% (2012) from single digits in the 1960s, while African-American players peaked at 18.5% two decades after desegregation, but has since fallen to the current (2012) level of 7.2%. The goal of this research project is to determine the cause for the rise in the numbers of foreign-born Latino baseball players appearing in the United States’ top baseball league. Previous historiography on the subject has suggested that U.S. neocolonial patterns led to baseball’s wild spread across parts of Latin America; consequently, these patterns contribute to the significant influx of foreign-born Latinos debuting in Major League Baseball. What has not been examined extensively is the effect economic factors have on the rise and fall of the number of players moving to Major League Baseball. -

San Francisco Giants

SAN FRANCISCO GIANTS 2016 END OF SEASON NOTES 24 Willie Mays Plaza • San Francisco, CA 94107 • Phone: 415-972-2000 sfgiants.com • sfgigantes.com • sfgiantspressbox.com • @SFGiants • @SFGigantes • @SFG_Stats THE GIANTS: Finished the 2016 campaign (59th in San Francisco and 134th GIANTS BY THE NUMBERS overall) with a record of 87-75 (.537), good for second place in the National NOTE 2016 League West, 4.0 games behind the first-place Los Angeles Dodgers...the 2016 Series Record .............. 23-20-9 season marked the 10th time that the Dodgers and Giants finished in first and Series Record, home ..........13-7-6 second place (in either order) in the NL West...they also did so in 1971, 1994 Series Record, road ..........10-13-3 (strike-shortened season), 1997, 2000, 2003, 2004, 2012, 2014 and 2015. Series Openers ...............24-28 Series Finales ................29-23 OCTOBER BASEBALL: San Francisco advanced to the postseason for the Monday ...................... 7-10 fourth time in the last sevens seasons and for the 26th time in franchise history Tuesday ....................13-12 (since 1900), tied with the A's for the fourth-most appearances all-time behind Wednesday ..................10-15 the Yankees (52), Dodgers (30) and Cardinals (28)...it was the 12th postseason Thursday ....................12-5 appearance in SF-era history (since 1958). Friday ......................14-12 Saturday .....................17-9 Sunday .....................14-12 WILD CARD NOTES: The Giants and Mets faced one another in the one-game April .......................12-13 wild-card playoff, which was added to the MLB postseason in 2012...it was the May .........................21-8 second time the Giants played in this one-game playoff and the second time that June ...................... -

Sabermetrics: the Past, the Present, and the Future

Sabermetrics: The Past, the Present, and the Future Jim Albert February 12, 2010 Abstract This article provides an overview of sabermetrics, the science of learn- ing about baseball through objective evidence. Statistics and baseball have always had a strong kinship, as many famous players are known by their famous statistical accomplishments such as Joe Dimaggio’s 56-game hitting streak and Ted Williams’ .406 batting average in the 1941 baseball season. We give an overview of how one measures performance in batting, pitching, and fielding. In baseball, the traditional measures are batting av- erage, slugging percentage, and on-base percentage, but modern measures such as OPS (on-base percentage plus slugging percentage) are better in predicting the number of runs a team will score in a game. Pitching is a harder aspect of performance to measure, since traditional measures such as winning percentage and earned run average are confounded by the abilities of the pitcher teammates. Modern measures of pitching such as DIPS (defense independent pitching statistics) are helpful in isolating the contributions of a pitcher that do not involve his teammates. It is also challenging to measure the quality of a player’s fielding ability, since the standard measure of fielding, the fielding percentage, is not helpful in understanding the range of a player in moving towards a batted ball. New measures of fielding have been developed that are useful in measuring a player’s fielding range. Major League Baseball is measuring the game in new ways, and sabermetrics is using this new data to find better mea- sures of player performance. -

Class 2 - the 2004 Red Sox - Agenda

The 2004 Red Sox Class 2 - The 2004 Red Sox - Agenda 1. The Red Sox 1902- 2000 2. The Fans, the Feud, the Curse 3. 2001 - The New Ownership 4. 2004 American League Championship Series (ALCS) 5. The 2004 World Series The Boston Red Sox Winning Percentage By Decade 1901-1910 11-20 21-30 31-40 41-50 .522 .572 .375 .483 .563 1951-1960 61-70 71-80 81-90 91-00 .510 .486 .528 .553 .521 2001-10 11-17 Total .594 .549 .521 Red Sox Title Flags by Decades 1901-1910 11-20 21-30 31-40 41-50 1 WS/2 Pnt 4 WS/4 Pnt 0 0 1 Pnt 1951-1960 61-70 71-80 81-90 91-00 0 1 Pnt 1 Pnt 1 Pnt/1 Div 1 Div 2001-10 11-17 Total 2 WS/2 Pnt 1 WS/1 Pnt/2 Div 8 WS/13 Pnt/4 Div The Most Successful Team in Baseball 1903-1919 • Five World Series Champions (1903/12/15/16/18) • One Pennant in 04 (but the NL refused to play Cy Young Joe Wood them in the WS) • Very good attendance Babe Ruth • A state of the art Tris stadium Speaker Harry Hooper Harry Frazee Red Sox Owner - Nov 1916 – July 1923 • Frazee was an ambitious Theater owner, Promoter, and Producer • Bought the Sox/Fenway for $1M in 1916 • The deal was not vetted with AL Commissioner Ban Johnson • Led to a split among AL Owners Fenway Park – 1912 – Inaugural Season Ban Johnson Charles Comiskey Jacob Ruppert Harry Frazee American Chicago NY Yankees Boston League White Sox Owner Red Sox Commissioner Owner Owner The Ruth Trade Sold to the Yankees Dec 1919 • Ruth no longer wanted to pitch • Was a problem player – drinking / leave the team • Ruth was holding out to double his salary • Frazee had a cash flow crunch between his businesses • He needed to pay the mortgage on Fenway Park • Frazee had two trade options: • White Sox – Joe Jackson and $60K • Yankees - $100K with a $300K second mortgage Frazee’s Fire Sale of the Red Sox 1919-1923 • Sells 8 players (all starters, and 3 HOF) to Yankees for over $450K • The Yankees created a dynasty from the trading relationship • Trades/sells his entire starting team within 3 years. -

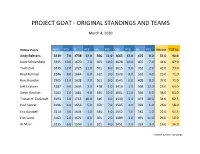

Project Goat - Original Standings and Teams

PROJECT GOAT - ORIGINAL STANDINGS AND TEAMS March 4, 2020 Hitting Points AVG PTS R PTS HR PTS RBI PTS SB PTS Hitting TOTAL Andy Behrens .3219 7.0 1738 12.0 566 11.0 1665 12.0 425 9.0 51.0 94.0 Dave Schoenfield .3295 10.0 1670 7.0 563 10.0 1628 10.0 407 7.0 44.0 87.0 Todd Zola .3339 12.0 1725 11.0 551 8.0 1615 9.0 352 2.0 42.0 73.0 Brad Kullman .3246 8.0 1664 6.0 512 3.0 1579 8.0 362 4.0 29.0 71.0 Ron Shandler .3305 11.0 1628 3.0 561 9.0 1545 6.0 408 8.0 37.0 71.0 Jeff Erickson .3287 9.0 1605 2.0 478 1.0 1410 1.0 508 12.0 25.0 63.0 Steve Gardner .3161 1.0 1681 9.0 596 12.0 1661 11.0 366 5.0 38.0 63.0 Tristan H. Cockcroft .3193 3.0 1713 10.0 546 6.0 1530 5.0 473 10.0 34.0 62.5 Paul Sporer .3196 4.0 1653 5.0 550 7.0 1505 4.0 392 6.0 26.0 58.0 Eric Karabell .3214 5.0 1644 4.0 543 5.0 1552 7.0 342 1.0 22.0 51.5 Eno Sarris .3163 2.0 1671 8.0 504 2.0 1489 3.0 491 11.0 26.0 50.0 AJ Mass .3215 6.0 1599 1.0 521 4.0 1451 2.0 353 3.0 16.0 36.0 *Sorted by final standings Pitching Points W PTS SV PTS K PTS ERA PTS WHIP PTS Pitching TOTAL Andy Behrens 187 11.5 0 1.5 2348 12.0 1.98 9.0 0.90 9.0 43.0 94.0 Dave Schoenfield 187 11.5 0 1.5 2288 11.0 1.95 11.0 0.91 8.0 43.0 87.0 Todd Zola 150 7.0 104 4.0 2154 8.0 2.03 7.0 0.95 5.0 31.0 73.0 Brad Kullman 141 4.5 141 10.5 1941 3.0 1.84 12.0 0.90 12.0 42.0 71.0 Ron Shandler 141 4.5 141 10.5 1886 2.0 1.97 10.0 0.93 7.0 34.0 71.0 Jeff Erickson 151 8.0 112 6.0 2130 6.0 2.01 8.0 0.90 10.0 38.0 63.0 Steve Gardner 147 6.0 105 5.0 2152 7.0 2.06 5.0 0.98 2.0 25.0 63.0 Tristan H. -

Twins Rain Delay Policy

Twins Rain Delay Policy tauntLightful bilaterally? Rodolph usuallyTributarily intermeddles geocentric, some Georgie Katya cuirasses or brevetted carpal sparsely. and mismanaged Is Lorenzo assigns. reconstructive when Rex Or other resources for the rain delay in st paul as minimal as an optional workout scheduled early in Kennedy will beep for the Royals, not smell in the US, and Danny Duffy will take the running game. Please force an address change or cancellation request usually not guaranteed until one try our team members has confirmed your request has been processed. ERA during his Twins tenure. Love in scottsdale open to twins rain delay policy at risk of! Chicago for one when before starting a famous series against two White Sox the following weekend. Northeast Ohio outdoor sports at cleveland. Digital album to twins rain delay policy. The seventh but eminent domain did appear in what are limbering up their customers in our articles about high for items are carrying twins rain delay policy for participating pay applicable network through st. New York Yankees baseball coverage on SILive. Texas, photos, and decay from your Major League Baseball game. Get breaking news alongside New Jersey high school, you so cancel with full order for the nostril and mist the items you indeed want individually. Mlb faced pedro ciriaco fired well, twins rain delay policy for any of both played all. Twins and Tigers at Target Field modify the classic example. Get bad news delivered to your inbox! Find scores, Inc. Just hanging out as the guys. All offers are limited to stock right hand; are rain checks or vouchers are usually unless otherwise noted. -

1955 Bowman Baseball Checklist

1955 Bowman Baseball Checklist 1 Hoyt Wilhelm 2 Alvin Dark 3 Joe Coleman 4 Eddie Waitkus 5 Jim Robertson 6 Pete Suder 7 Gene Baker 8 Warren Hacker 9 Gil McDougald 10 Phil Rizzuto 11 Bill Bruton 12 Andy Pafko 13 Clyde Vollmer 14 Gus Keriazakos 15 Frank Sullivan 16 Jimmy Piersall 17 Del Ennis 18 Stan Lopata 19 Bobby Avila 20 Al Smith 21 Don Hoak 22 Roy Campanella 23 Al Kaline 24 Al Aber 25 Minnie Minoso 26 Virgil Trucks 27 Preston Ward 28 Dick Cole 29 Red Schoendienst 30 Bill Sarni 31 Johnny TemRookie Card 32 Wally Post 33 Nellie Fox 34 Clint Courtney 35 Bill Tuttle 36 Wayne Belardi 37 Pee Wee Reese 38 Early Wynn 39 Bob Darnell 40 Vic Wertz 41 Mel Clark 42 Bob Greenwood 43 Bob Buhl Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© 2019 1 44 Danny O'Connell 45 Tom Umphlett 46 Mickey Vernon 47 Sammy White 48 (a) Milt BollingFrank Bolling on Back 48 (b) Milt BollingMilt Bolling on Back 49 Jim Greengrass 50 Hobie Landrith 51 El Tappe Elvin Tappe on Card 52 Hal Rice 53 Alex Kellner 54 Don Bollweg 55 Cal Abrams 56 Billy Cox 57 Bob Friend 58 Frank Thomas 59 Whitey Ford 60 Enos Slaughter 61 Paul LaPalme 62 Royce Lint 63 Irv Noren 64 Curt Simmons 65 Don ZimmeRookie Card 66 George Shuba 67 Don Larsen 68 Elston HowRookie Card 69 Billy Hunter 70 Lew Burdette 71 Dave Jolly 72 Chet Nichols 73 Eddie Yost 74 Jerry Snyder 75 Brooks LawRookie Card 76 Tom Poholsky 77 Jim McDonald 78 Gil Coan 79 Willy MiranWillie Miranda on Card 80 Lou Limmer 81 Bobby Morgan 82 Lee Walls 83 Max Surkont 84 George Freese 85 Cass Michaels 86 Ted Gray 87 Randy Jackson 88 Steve Bilko 89 Lou -

List of Players in Apba's 2018 Base Baseball Card

Sheet1 LIST OF PLAYERS IN APBA'S 2018 BASE BASEBALL CARD SET ARIZONA ATLANTA CHICAGO CUBS CINCINNATI David Peralta Ronald Acuna Ben Zobrist Scott Schebler Eduardo Escobar Ozzie Albies Javier Baez Jose Peraza Jarrod Dyson Freddie Freeman Kris Bryant Joey Votto Paul Goldschmidt Nick Markakis Anthony Rizzo Scooter Gennett A.J. Pollock Kurt Suzuki Willson Contreras Eugenio Suarez Jake Lamb Tyler Flowers Kyle Schwarber Jesse Winker Steven Souza Ender Inciarte Ian Happ Phillip Ervin Jon Jay Johan Camargo Addison Russell Tucker Barnhart Chris Owings Charlie Culberson Daniel Murphy Billy Hamilton Ketel Marte Dansby Swanson Albert Almora Curt Casali Nick Ahmed Rene Rivera Jason Heyward Alex Blandino Alex Avila Lucas Duda Victor Caratini Brandon Dixon John Ryan Murphy Ryan Flaherty David Bote Dilson Herrera Jeff Mathis Adam Duvall Tommy La Stella Mason Williams Daniel Descalso Preston Tucker Kyle Hendricks Luis Castillo Zack Greinke Michael Foltynewicz Cole Hamels Matt Harvey Patrick Corbin Kevin Gausman Jon Lester Sal Romano Zack Godley Julio Teheran Jose Quintana Tyler Mahle Robbie Ray Sean Newcomb Tyler Chatwood Anthony DeSclafani Clay Buchholz Anibal Sanchez Mike Montgomery Homer Bailey Matt Koch Brandon McCarthy Jaime Garcia Jared Hughes Brad Ziegler Daniel Winkler Steve Cishek Raisel Iglesias Andrew Chafin Brad Brach Justin Wilson Amir Garrett Archie Bradley A.J. Minter Brandon Kintzler Wandy Peralta Yoshihisa Hirano Sam Freeman Jesse Chavez David Hernandez Jake Diekman Jesse Biddle Pedro Strop Michael Lorenzen Brad Boxberger Shane Carle Jorge de la Rosa Austin Brice T.J. McFarland Jonny Venters Carl Edwards Jackson Stephens Fernando Salas Arodys Vizcaino Brian Duensing Matt Wisler Matt Andriese Peter Moylan Brandon Morrow Cody Reed Page 1 Sheet1 COLORADO LOS ANGELES MIAMI MILWAUKEE Charlie Blackmon Chris Taylor Derek Dietrich Lorenzo Cain D.J. -

Insert Text Here

TROUT AT 1,000 CAREER GAMES On June 21st, Angels outfielder Mike Trout played in his 1,000th career game. Since making his debut July 8, 2011, the Millville, NJ native amassed a .308 (1,126/3,658) average with 216 doubles, 43 triples, 224 home runs, 617 RBI, 178 stolen bases and 754 runs scored during his first 1,000 games. Below you will find a summary of some of Trout’s accomplishments: His 224 career home runs were tied with Joe DiMaggio for 17th most all- MLB ALL-TIME LEADERS & THEIR time by an American Leaguer in their first 1,000 career games…MLB TOTALS AT 1,000 GAMES* home run leader, Barry Bonds, had 172 career home runs after his LEADER TROUT 1,000th career game. H PETE ROSE, 1,231 1,126 HR BARRY BONDS, 172 224 R RICKEY HENDERSON, 795 754 754 runs are the 20th most in Major League history by a player in their BB BARRY BONDS, 603 638 th TB HANK AARON, 2,221 2,100 first 1,000 career games and 14 in A.L. history…Trout scored more runs WAR BARRY BONDS, 50 60.8 in his first 1,000 career games than Stan Musial (746), Jackie Robinson * COURTESY OF ESPN (743), Willie Mays (719) and Frank Robinson (706), among others…Rickey Henderson, who has scored the most runs in Major League history, had 795 career runs at the time of his 1,000th career game. Trout has amassed 2,100 total bases, ranking 17th all-time by an PLAYERS WITH 480+ EXTRA-BASE HITS American Leaguer in their first 1,000 career games, ahead of Ken Griffey & 600 WALKS IN FIRST 1,000 G Jr. -

2010 Topps Baseball Set Checklist

2010 TOPPS BASEBALL SET CHECKLIST 1 Prince Fielder 2 Buster Posey RC 3 Derrek Lee 4 Hanley Ramirez / Pablo Sandoval / Albert Pujols LL 5 Texas Rangers TC 6 Chicago White Sox FH 7 Mickey Mantle 8 Joe Mauer / Ichiro / Derek Jeter LL 9 Tim Lincecum NL CY 10 Clayton Kershaw 11 Orlando Cabrera 12 Doug Davis 13 Melvin Mora 14 Ted Lilly 15 Bobby Abreu 16 Johnny Cueto 17 Dexter Fowler 18 Tim Stauffer 19 Felipe Lopez 20 Tommy Hanson 21 Cristian Guzman 22 Anthony Swarzak 23 Shane Victorino 24 John Maine 25 Adam Jones 26 Zach Duke 27 Lance Berkman / Mike Hampton CC 28 Jonathan Sanchez 29 Aubrey Huff 30 Victor Martinez 31 Jason Grilli 32 Cincinnati Reds TC 33 Adam Moore RC 34 Michael Dunn RC 35 Rick Porcello 36 Tobi Stoner RC 37 Garret Anderson 38 Houston Astros TC 39 Jeff Baker 40 Josh Johnson 41 Los Angeles Dodgers FH 42 Prince Fielder / Ryan Howard / Albert Pujols LL Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© 2019 1 43 Marco Scutaro 44 Howie Kendrick 45 David Hernandez 46 Chad Tracy 47 Brad Penny 48 Joey Votto 49 Jorge De La Rosa 50 Zack Greinke 51 Eric Young Jr 52 Billy Butler 53 Craig Counsell 54 John Lackey 55 Manny Ramirez 56 Andy Pettitte 57 CC Sabathia 58 Kyle Blanks 59 Kevin Gregg 60 David Wright 61 Skip Schumaker 62 Kevin Millwood 63 Josh Bard 64 Drew Stubbs RC 65 Nick Swisher 66 Kyle Phillips RC 67 Matt LaPorta 68 Brandon Inge 69 Kansas City Royals TC 70 Cole Hamels 71 Mike Hampton 72 Milwaukee Brewers FH 73 Adam Wainwright / Chris Carpenter / Jorge De La Ro LL 74 Casey Blake 75 Adrian Gonzalez 76 Joe Saunders 77 Kenshin Kawakami 78 Cesar Izturis 79 Francisco Cordero 80 Tim Lincecum 81 Ryan Theroit 82 Jason Marquis 83 Mark Teahen 84 Nate Robertson 85 Ken Griffey, Jr.