Rabindra Nritya: the Cultural And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Letter Correspondences of Rabindranath Tagore: a Study

Annals of Library and Information Studies Vol. 59, June 2012, pp. 122-127 Letter correspondences of Rabindranath Tagore: A Study Partha Pratim Raya and B.K. Senb aLibrarian, Instt. of Education, Visva-Bharati, West Bengal, India, E-mail: [email protected] b80, Shivalik Apartments, Alakananda, New Delhi-110 019, India, E-mail:[email protected] Received 07 May 2012, revised 12 June 2012 Published letters written by Rabindranath Tagore counts to four thousand ninety eight. Besides family members and Santiniketan associates, Tagore wrote to different personalities like litterateurs, poets, artists, editors, thinkers, scientists, politicians, statesmen and government officials. These letters form a substantial part of intellectual output of ‘Tagoreana’ (all the intellectual output of Rabindranath). The present paper attempts to study the growth pattern of letters written by Rabindranath and to find out whether it follows Bradford’s Law. It is observed from the study that Rabindranath wrote letters throughout his literary career to three hundred fifteen persons covering all aspects such as literary, social, educational, philosophical as well as personal matters and it does not strictly satisfy Bradford’s bibliometric law. Keywords: Rabindranath Tagore, letter correspondences, bibliometrics, Bradfords Law Introduction a family man and also as a universal man with his Rabindranath Tagore is essentially known to the many faceted vision and activities. Tagore’s letters world as a poet. But he was a great short-story writer, written to his niece Indira Devi Chaudhurani dramatist and novelist, a powerful author of essays published in Chhinapatravali1 written during 1885- and lectures, philosopher, composer and singer, 1895 are not just letters but finer prose from where innovator in education and rural development, actor, the true picture of poet Rabindranath as well as director, painter and cultural ambassador. -

IP Tagore Issue

Vol 24 No. 2/2010 ISSN 0970 5074 IndiaVOL 24 NO. 2/2010 Perspectives Six zoomorphic forms in a line, exhibited in Paris, 1930 Editor Navdeep Suri Guest Editor Udaya Narayana Singh Director, Rabindra Bhavana, Visva-Bharati Assistant Editor Neelu Rohra India Perspectives is published in Arabic, Bahasa Indonesia, Bengali, English, French, German, Hindi, Italian, Pashto, Persian, Portuguese, Russian, Sinhala, Spanish, Tamil and Urdu. Views expressed in the articles are those of the contributors and not necessarily of India Perspectives. All original articles, other than reprints published in India Perspectives, may be freely reproduced with acknowledgement. Editorial contributions and letters should be addressed to the Editor, India Perspectives, 140 ‘A’ Wing, Shastri Bhawan, New Delhi-110001. Telephones: +91-11-23389471, 23388873, Fax: +91-11-23385549 E-mail: [email protected], Website: http://www.meaindia.nic.in For obtaining a copy of India Perspectives, please contact the Indian Diplomatic Mission in your country. This edition is published for the Ministry of External Affairs, New Delhi by Navdeep Suri, Joint Secretary, Public Diplomacy Division. Designed and printed by Ajanta Offset & Packagings Ltd., Delhi-110052. (1861-1941) Editorial In this Special Issue we pay tribute to one of India’s greatest sons As a philosopher, Tagore sought to balance his passion for – Rabindranath Tagore. As the world gets ready to celebrate India’s freedom struggle with his belief in universal humanism the 150th year of Tagore, India Perspectives takes the lead in and his apprehensions about the excesses of nationalism. He putting together a collection of essays that will give our readers could relinquish his knighthood to protest against the barbarism a unique insight into the myriad facets of this truly remarkable of the Jallianwala Bagh massacre in Amritsar in 1919. -

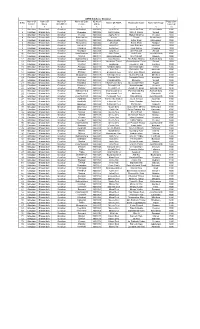

Rule Section

Rule Section CO 827/2015 Shyamal Middya vs Dhirendra Nath Middya CO 542/1988 Jayadratha Adak vs Kadan Bala Adak CO 1403/2015 Sankar Narayan das vs A.K.Banerjee CO 1945/2007 Pradip kr Roy vs Jali Devi & Ors CO 2775/2012 Haripada Patra vs Jayanta Kr Patra CO 3346/1989 + CO 3408/1992 R.B.Mondal vs Syed Ali Mondal CO 1312/2007 Niranjan Sen vs Sachidra lal Saha CO 3770/2011 lily Ghose vs Paritosh Karmakar & ors CO 4244/2006 Provat kumar singha vs Afgal sk CO 2023/2006 Piar Ali Molla vs Saralabala Nath CO 2666/2005 Purnalal seal vs M/S Monindra land Building corporation ltd CO 1971/2006 Baidyanath Garain& ors vs Hafizul Fikker Ali CO 3331/2004 Gouridevi Paswan vs Rajendra Paswan CR 3596 S/1990 Bakul Rani das &ors vs Suchitra Balal Pal CO 901/1995 Jeewanlal (1929) ltd& ors vs Bank of india CO 995/2002 Susan Mantosh vs Amanda Lazaro CO 3902/2012 SK Abdul latik vs Firojuddin Mollick & ors CR 165 S/1990 State of west Bengal vs Halema Bibi & ors CO 3282/2006 Md kashim vs Sunil kr Mondal CO 3062/2011 Ajit kumar samanta vs Ranjit kumar samanta LIST OF PENDING BENCH LAWAZIMA : (F.A. SECTION) Sl. No. Case No. Cause Title Advocate’s Name 1. FA 114/2016 Union Bank of India Mr. Ranojit Chowdhury Vs Empire Pratisthan & Trading 2. FA 380/2008 Bijon Biswas Smt. Mita Bag Vs Jayanti Biswas & Anr. 3. FA 116/2016 Sarat Tewari Ms. Nibadita Karmakar Vs Swapan Kr. Tewari 4. -

Secondary Indian Culture and Heritage

Culture: An Introduction MODULE - I Understanding Culture Notes 1 CULTURE: AN INTRODUCTION he English word ‘Culture’ is derived from the Latin term ‘cult or cultus’ meaning tilling, or cultivating or refining and worship. In sum it means cultivating and refining Ta thing to such an extent that its end product evokes our admiration and respect. This is practically the same as ‘Sanskriti’ of the Sanskrit language. The term ‘Sanskriti’ has been derived from the root ‘Kri (to do) of Sanskrit language. Three words came from this root ‘Kri; prakriti’ (basic matter or condition), ‘Sanskriti’ (refined matter or condition) and ‘vikriti’ (modified or decayed matter or condition) when ‘prakriti’ or a raw material is refined it becomes ‘Sanskriti’ and when broken or damaged it becomes ‘vikriti’. OBJECTIVES After studying this lesson you will be able to: understand the concept and meaning of culture; establish the relationship between culture and civilization; Establish the link between culture and heritage; discuss the role and impact of culture in human life. 1.1 CONCEPT OF CULTURE Culture is a way of life. The food you eat, the clothes you wear, the language you speak in and the God you worship all are aspects of culture. In very simple terms, we can say that culture is the embodiment of the way in which we think and do things. It is also the things Indian Culture and Heritage Secondary Course 1 MODULE - I Culture: An Introduction Understanding Culture that we have inherited as members of society. All the achievements of human beings as members of social groups can be called culture. -

Government of Assam OFFICE of the COMMISSIONER of TAXES

Government of Assam OFFICE OF THE COMMISSIONER OF TAXES PROVISIONAL LIST OF CANDIDATES FOR THE POSTS OF JUNIOR ASSISTANT UNDER THE COMMISSIONER OF TAXES, GOVERNMENT OF ASSAM Sl No Online Application No. Name of the CandidateFather Name Mother Name 1 199005617 A R AMIN ULLA RAHIMUDDIN AHMED KARIMAN NESSA 2 199005659 A R ATIQUE ULLA RAHIMUDDIN AHMED KARIMAN NESSA 3 199003745 AARTI KUMARI RAM CHANDAR PRASAD SADHNA DEVI 4 199008979 ABANI DOLEY KASHINATH DOLEY ANJULI DOLEY 5 199010295 ABANI KANTA SINGHA RADHA KANTA SINGHA ABHOYA RANI SINHA 6 199008302 ABANI PHUKAN DILESWAR PHUKAN LICI PHANGCHOPI 7 199003746 ABDUL AHAD CHOUDHURY ATAUR RAHMAN CHOUDHURY RABIA KHANAM CHOUDHURY 8 199011920 ABDUL BATEN KASEM ALI SHUKITAN NESSA 9 199006876 ABDUL HAMIM LASKAR ABDUL MANAF LASKAR HALIMA KHATUN LASKAR 10 199002148 ABDUL HASIM MD NAZMUL HAQUE DELANGISH BEGUM 11 199009460 ABDUL HUSSAIN BULMAJAN ALI AJEBUN NESSA BEGUM 12 199001151 ABDUL KADIR ALI ANOWAR HUSSAIN AIAJUN BEGUM 13 199003077 ABDUL KHAN NUR HUSSAIN KHAN MONICA KHATOON 14 199002194 ABDUL MAHSIN HOQUE MD NAZMUL HOQUE DELANGISH BEGUM 15 199009870 ABDUL MALIK MUZAMMEL HOQUE AZEDA BEGUM 16 199010603 ABDUL MANNAN JULHAS ALI FIROZA BEGUM 17 199012475 ABDUL MAZID FAZAR ALI RUPJAN BEGUM 18 199005498 ABDUL MOTLIB ABDUL AZIM ILA BEGUM 19 199000721 ABDUL MUNIM AHMED ABDUS SAMAD AHMED NASIM BANU AKAND 20 199010439 ABDUL ROSHID SURHAB ALI MAHARUMA BEGUM 21 199003052 ABDUL SAYED ABDUL LATIF MEAH SAIRA KHATUN 22 199003735 ABDUL WADUD HAKIM ALI MANOWARA BEGUM 23 199000601 ABDUL WASHIF AHMED HASIB AHMED ANUARA -

Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan Title Accno Language Author / Script Folios DVD Remarks

www.ignca.gov.in Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan Title AccNo Language Author / Script Folios DVD Remarks CF, All letters to A 1 Bengali Many Others 75 RBVB_042 Rabindranath Tagore Vol-A, Corrected, English tr. A Flight of Wild Geese 66 English Typed 112 RBVB_006 By K.C. Sen A Flight of Wild Geese 338 English Typed 107 RBVB_024 Vol-A A poems by Dwijendranath to Satyendranath and Dwijendranath Jyotirindranath while 431(B) Bengali Tagore and 118 RBVB_033 Vol-A, presenting a copy of Printed Swapnaprayana to them A poems in English ('This 397(xiv Rabindranath English 1 RBVB_029 Vol-A, great utterance...') ) Tagore A song from Tapati and Rabindranath 397(ix) Bengali 1.5 RBVB_029 Vol-A, stage directions Tagore A. Perumal Collection 214 English A. Perumal ? 102 RBVB_101 CF, All letters to AA 83 Bengali Many others 14 RBVB_043 Rabindranath Tagore Aakas Pradeep 466 Bengali Rabindranath 61 RBVB_036 Vol-A, Tagore and 1 www.ignca.gov.in Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan Title AccNo Language Author / Script Folios DVD Remarks Sudhir Chandra Kar Aakas Pradeep, Chitra- Bichitra, Nabajatak, Sudhir Vol-A, corrected by 263 Bengali 40 RBVB_018 Parisesh, Prahasinee, Chandra Kar Rabindranath Tagore Sanai, and others Indira Devi Bengali & Choudhurani, Aamar Katha 409 73 RBVB_029 Vol-A, English Unknown, & printed Indira Devi Aanarkali 401(A) Bengali Choudhurani 37 RBVB_029 Vol-A, & Unknown Indira Devi Aanarkali 401(B) Bengali Choudhurani 72 RBVB_029 Vol-A, & Unknown Aarogya, Geetabitan, 262 Bengali Sudhir 72 RBVB_018 Vol-A, corrected by Chhelebele-fef. Rabindra- Chandra -

JA-097-17-III (Rabindra Sangit) Inst.P65

www.a2zSubjects.com PAPER-III RABINDRA SANGIT Signature and Name of Invigilator 1. (Signature) __________________________ OMR Sheet No. : ............................................... (Name) ____________________________ (To be filled by the Candidate) 2. (Signature) __________________________ Roll No. (Name) ____________________________ (In figures as per admission card) Roll No.________________________________ J A 0 9 7 1 7 (In words) 1 Time : 2 /2 hours] [Maximum Marks : 150 Number of Pages in this Booklet : 32 Number of Questions in this Booklet : 75 Instructions for the Candidates ¯Ö¸üßõÖÖÙ£ÖµÖÖë Ûêú ×»Ö‹ ×®Ö¤ìü¿Ö 1. Write your roll number in the space provided on the top of 1. ‡ÃÖ ¯Öéšü Ûêú ‰ú¯Ö¸ü ×®ÖµÖŸÖ Ã£ÖÖ®Ö ¯Ö¸ü †¯Ö®ÖÖ ¸üÖê»Ö ®Ö´²Ö¸ü ×»Ö×ÜÖ‹ … this page. 2. ‡ÃÖ ¯ÖÏ¿®Ö-¯Ö¡Ö ´Öë ¯Ö“ÖÆü¢Ö¸ü ²ÖÆãü×¾ÖÛú»¯ÖßµÖ ¯ÖÏ¿®Ö Æïü … 2. This paper consists of seventy five multiple-choice type of 3. ¯Ö¸üßõÖÖ ¯ÖÏÖ¸ü´³Ö ÆüÖê®Öê ¯Ö¸ü, ¯ÖÏ¿®Ö-¯Öã×ßÖÛúÖ †Ö¯ÖÛúÖê ¤êü ¤üß •ÖÖµÖêÝÖß … ¯ÖÆü»Öê questions. ¯ÖÖÑ“Ö ×´Ö®Ö™ü †Ö¯ÖÛúÖê ¯ÖÏ¿®Ö-¯Öã×ßÖÛúÖ ÜÖÖê»Ö®Öê ŸÖ£ÖÖ ˆÃÖÛúß ×®Ö´®Ö×»Ö×ÜÖŸÖ 3. At the commencement of examination, the question booklet •ÖÖÑ“Ö Ûêú ×»Ö‹ פüµÖê •ÖÖµÖëÝÖê, וÖÃÖÛúß •ÖÖÑ“Ö †Ö¯ÖÛúÖê †¾Ö¿µÖ Ûú¸ü®Öß Æîü : will be given to you. In the first 5 minutes, you are requested (i) to open the booklet and compulsorily examine it as below : ¯ÖÏ¿®Ö-¯Öã×ßÖÛúÖ ÜÖÖê»Ö®Öê Ûêú ×»Ö‹ ¯Öã×ßÖÛúÖ ¯Ö¸ü »ÖÝÖß ÛúÖÝÖ•Ö Ûúß ÃÖᯙ (i) To have access to the Question Booklet, tear off the paper ÛúÖê ±úÖ›Ìü »Öë … ÜÖã»Öß Æãü‡Ô µÖÖ ×²Ö®ÖÖ Ã™üßÛú¸ü-ÃÖᯙ Ûúß ¯Öã×ßÖÛúÖ seal on the edge of this cover page. -

Compiled Ghazipur

ASHA Database Ghazipur Name Of Name Of Name Of Name Of Sub- ID No.of Population S.No. Name Of ASHA Husband's Name Name Of Village District Block CHC/BPHC Centre ASHA Covered 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 1 Ghazipur Bhawarkole Gondour Mirjabad 3003001 Aarti Devi Awadesh Ram Devchandpur 1000 2 Ghazipur Bhawarkole Gondour Chandpur 3003002 Aarti Thakur Shiv Ji Thakur Sonadi 1000 3 Ghazipur Bhawarkole Gondour Veerpur 3003003 Aasha Devi Madan Sharma Veerpur 1000 4 Ghazipur Bhawarkole Gondour Pakhanpura 3003004 Aasiya Taukir Pakhanpura 1000 5 Ghazipur Bhawarkole Gondour Bhawarkole 3003005 Afsana Khatun Akbar Khan Maheshpur 1000 6 Ghazipur Bhawarkole Gondour Bhawarkole 3003006 Ahamadi Kalim Khan Ranipur 1000 7 Ghazipur Bhawarkole Gondour Awathahi 3003007 Anita Devi Jang Bahadur Awathahi 1000 8 Ghazipur Bhawarkole Gondour Khardiya 3003008 Anita Devi Indal Dubey Khardiya 1000 9 Ghazipur Bhawarkole Gondour Chandpur 3003009 Anju Devi Om Prakash Sonadi 1000 10 Ghazipur Bhawarkole Gondour Joga Musahib 3003010 Anju Gupta AnilKharwar Gupta Joga Musahib 1000 11 Ghazipur Bhawarkole Gondour Maniya 3003011 Anju Kushwaha Om Prakash Maniya 1000 12 Ghazipur Bhawarkole Gondour Sukhadehara 3003012 Anju Shukla Brij kushwahaBihari Shukla Sukhadehara 1000 13 Ghazipur Bhawarkole Gondour Chandpur 3003013 Anupama Tiwari Ramashankar Tiwari Sonadi 1000 14 Ghazipur Bhawarkole Gondour Gondour 3003014 Arpita Rai Umesh Kr. Rai Gondour 1000 15 Ghazipur Bhawarkole Gondour Amrupur 3003015 Bandana Ojha Harivansh Ojha Vatha 1000 16 Ghazipur Bhawarkole Gondour Awathahi 3003016 Bebi Rai -

Elective English - III DENG202

Elective English - III DENG202 ELECTIVE ENGLISH—III Copyright © 2014, Shraddha Singh All rights reserved Produced & Printed by EXCEL BOOKS PRIVATE LIMITED A-45, Naraina, Phase-I, New Delhi-110028 for Lovely Professional University Phagwara SYLLABUS Elective English—III Objectives: To introduce the student to the development and growth of various trends and movements in England and its society. To make students analyze poems critically. To improve students' knowledge of literary terminology. Sr. Content No. 1 The Linguist by Geetashree Chatterjee 2 A Dream within a Dream by Edgar Allan Poe 3 Chitra by Rabindranath Tagore 4 Ode to the West Wind by P.B.Shelly. The Vendor of Sweets by R.K. Narayan 5 How Much Land does a Man Need by Leo Tolstoy 6 The Agony of Win by Malavika Roy Singh 7 Love Lives Beyond the Tomb by John Clare. The Traveller’s story of a Terribly Strange Bed by Wilkie Collins 8 Beggarly Heart by Rabindranath Tagore 9 Next Sunday by R.K. Narayan 10 A Lickpenny Lover by O’ Henry CONTENTS Unit 1: The Linguist by Geetashree Chatterjee 1 Unit 2: A Dream within a Dream by Edgar Allan Poe 7 Unit 3: Chitra by Rabindranath Tagore 21 Unit 4: Ode to the West Wind by P B Shelley 34 Unit 5: The Vendor of Sweets by R K Narayan 52 Unit 6: How Much Land does a Man Need by Leo Tolstoy 71 Unit 7: The Agony of Win by Malavika Roy Singh 84 Unit 8: Love Lives beyond the Tomb by John Clare 90 Unit 9: The Traveller's Story of a Terribly Strange Bed by Wilkie Collins 104 Unit 10: Beggarly Heart by Rabindranath Tagore 123 Unit 11: Next Sunday by -

1 1 RABINDRANATH TAGORE and ASIAN UNIVERSALISM SUGATA BOSE Gardiner Professor of History, Harvard University a World-Historical

1 1 RABINDRANATH TAGORE AND ASIAN UNIVERSALISM SUGATA BOSE Gardiner Professor of History, Harvard University A world-historical transformation is under way in the early twenty-first century as Asia recovers the global position it had lost in the late eighteenth century. Yet the idea of Asia and a spirit of Asian universalism were alive and articulated in a variety of registers during the period of European imperial domination. Rabindranath Tagore was one of the most creative exponents of an Asia-sense in the early twentieth century. “Each country of Asia will solve its own historical problems according to its strength, nature and need,” Tagore said during a visit to Iran in 1932, “but the lamp that they will each carry on their path to progress will converge to illuminate the common ray of knowledge...it is only when the light of the spirit glows that the bond of humanity becomes true.”1 On February 10, 1937, Tagore composed his poem on another continent, “Africa”, towards the end of his long and creative life in literature. Even more than the empathy for Africa’s history of ‘blood and tears’, what marked the poem was a searing sarcasm directed at the false universalist claims of an unnamed Europe. Even as the ‘barbaric greed of the civilized’ put on naked display their ‘shameless inhumanity’, church bells rang out in neighborhoods across the ocean in the name of a benign God, children played in their mother’s laps, and poets sang paeans to beauty.2 The sanctimonious hypocrisy of the colonizer stood in stark opposition to the wretched abjection of the colonized. -

Dr. BC Roy Engineering College (120)

Print this page Registration List for College : Dr. B. C. Roy Engineering College (120) B. Tech. General Entry B.Tech. in Computer Science & Engineering Provisional Registration Serial Student Father Mother Number 0001 AAQUIB EKRAM EKRAMUL HAQUE SADQUA ANJUM 141200110001 0002 ABHISHEK KESHRI MANOJ KUMAR KESHRI SHANTI DEVI 141200110002 0003 ABHISHEK KUMAR NAVIN KUMAR RUBY DEVI 141200110003 ABHISHEK KUMAR 0004 ASHOK SHAW SARITA SHAW 141200110004 SHAW 0005 ABITATHA MANDAL ARUN PRAKASH MANDAL MITRA MANDAL 141200110005 0006 ABU SAYEM ABUL FAZAL PARMINA BIBI 141200110006 0007 ADDRI MAJEE DEBABRATA MAJEE TAPU MAJEE 141200110007 0008 ADITYA KUMAR JHA SHAMBHU NATH JHA SUDHA DEVI 141200110008 0009 ADITYA NARAYAN SANJEEV KUMAR RENU KUMARI 141200110009 ASHIS KUMAR 0010 AGNISH CHOUDHURY SAMPA CHOUDHURY 141200110010 CHOUDHURY 0011 AISHWARYA MAYANK VIVEK KUMAR KAVITA KUMARI 141200110011 0012 AMARTYA DUTTA ANUP KUMAR DUTTA TANUJA DUTTA 141200110012 AWDHESH KUMAR 0013 AMIT KUMAR KIRAN DEVI 141200110013 MANDAL 0014 ANANNYA GOSWAMI ALOKE KUMAR GOSWAMI SUNITA GOSWAMI 141200110014 0015 ANJALI VERMA SHASHI KUMAR VERMA ARUNA VERMA 141200110015 0016 ANKIT AYUSH AJAY KUMAR THAKUR SARITA THAKUR 141200110016 HARIDWAR PRASAD 0017 ANKITA GUPTA MEERA GUPTA 141200110017 GUPTA 0018 ANKUSH MONDAL UTPAL MANDAL BITHIKA MANDAL 141200110018 0019 ANWESHA DHAR BHASKAR DHAR SHARMILA DHAR 141200110019 0020 ARITRA GANGULY UJJWAL KUMAR GANGULY KUHELI GANGULY 141200110020 0021 ARKA HAZRA BISWANATH HAZRA SIKHA HAZRA 141200110021 0022 ARKAPRABHA KAR ABHIJIT KAR SUPARNA KAR 141200110022 -

Visva-Bharati, Sangit-Bhavana Department of Rabindra Sangit, Dance & Drama CURRICULUM for UNDERGRADUATE COURSE CHOICE BASED CREDIT SYSTEM

Visva-Bharati, Sangit-Bhavana Department of Rabindra Sangit, Dance & Drama CURRICULUM FOR UNDERGRADUATE COURSE CHOICE BASED CREDIT SYSTEM COURSE CODE: DURATION: 3 COURSE CODE SIX SEMESTER BMS YEARS NO: 41 Sl.No Course Semester Credit Marks Full Marks . 1. Core Course - CC 14 Courses I-IV 14X6=84 14X75 1050 08 Courses Practical 06 Courses Theoretical 2. Discipline Specific Elective - DSE 04 Courses V-VI 4X6=24 4X75 300 03 Courses Practical 01 Courses Theoretical 3. Generic Elective Course – GEC 04 Course I-IV 4X6=24 4X75 300 03 Courses Practical 01 Courses Theoretical 4. Skill Enhancement Compulsory Course – SECC III-IV 2X2=4 2X25 50 02 Courses Theoretical 5. Ability Enhancement Compulsory Course – AECC I-II 2X2=4 2X25 50 02 Courses Theoretical 6. Tagore Studies - TS (Foundation Course) I-II 4X2=8 2X50 100 02 Courses Theoretical Total Courses 28 Semester IV Credits 148 Marks 1850 Page 1 of 109 CHOICE BASED CREDIT SYSTEM B.MUS (HONS) COURSE AND MARKS DISTRIBUTION STRUCTURE CC DSE GEC SECC AEC TS SEM C TOTA PRA THE PRA THE PRA THE THE THE THE L C O C O C O O O O I 75 75 - - 75 - - 25 50 300 II 75 75 - - 75 - - 25 50 300 III 150 75 - - 75 - 25 - - 325 IV 150 75 - - - 75 25 - - 325 V 75 75 150 - - - - - - 300 VI 75 75 75 75 - - - - - 300 TOTA 600 450 225 75 225 75 50 50 100 1850 L Page 2 of 109 CHOICE BASED CREDIT SYSTEM B.MUS (HONS) OUTLINE OF THE COURSE STRUCTURE COURSE COURSE TYPE CREDITS MARKS HOURS PER CODE WEEK SEMESTER-I CC-1 PRACTICAL 6 75 12 CC-2 THEORETICAL 6 75 6 GEC-1 PRACTICAL 6 75 12 AECC-1 THEORETICAL 2 25 2 TS-1 THEORETICAL