Avian Influenza Virus H9N2 Infections in Farmed Minks Chuanmei Zhang1,2†, Yang Xuan2†, Hu Shan2†, Haiyan Yang2, Jianlin Wang2, Ke Wang2, Guimei Li2 and Jian Qiao1*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Virus Goes Viral: an Educational Kit for Virology Classes

Souza et al. Virology Journal (2020) 17:13 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12985-020-1291-9 RESEARCH Open Access Virus goes viral: an educational kit for virology classes Gabriel Augusto Pires de Souza1†, Victória Fulgêncio Queiroz1†, Maurício Teixeira Lima1†, Erik Vinicius de Sousa Reis1, Luiz Felipe Leomil Coelho2 and Jônatas Santos Abrahão1* Abstract Background: Viruses are the most numerous entities on Earth and have also been central to many episodes in the history of humankind. As the study of viruses progresses further and further, there are several limitations in transferring this knowledge to undergraduate and high school students. This deficiency is due to the difficulty in designing hands-on lessons that allow students to better absorb content, given limited financial resources and facilities, as well as the difficulty of exploiting viral particles, due to their small dimensions. The development of tools for teaching virology is important to encourage educators to expand on the covered topics and connect them to recent findings. Discoveries, such as giant DNA viruses, have provided an opportunity to explore aspects of viral particles in ways never seen before. Coupling these novel findings with techniques already explored by classical virology, including visualization of cytopathic effects on permissive cells, may represent a new way for teaching virology. This work aimed to develop a slide microscope kit that explores giant virus particles and some aspects of animal virus interaction with cell lines, with the goal of providing an innovative approach to virology teaching. Methods: Slides were produced by staining, with crystal violet, purified giant viruses and BSC-40 and Vero cells infected with viruses of the genera Orthopoxvirus, Flavivirus, and Alphavirus. -

Virology Journal Biomed Central

Virology Journal BioMed Central Research Open Access Inhibition of Henipavirus fusion and infection by heptad-derived peptides of the Nipah virus fusion glycoprotein Katharine N Bossart†2, Bruce A Mungall†1, Gary Crameri1, Lin-Fa Wang1, Bryan T Eaton1 and Christopher C Broder*2 Address: 1CSIRO Livestock Industries, Australian Animal Health Laboratory, Geelong, Victoria 3220, Australia and 2Department of Microbiology and Immunology, Uniformed Services University, Bethesda, MD 20814, USA Email: Katharine N Bossart - [email protected]; Bruce A Mungall - [email protected]; Gary Crameri - [email protected]; Lin-Fa Wang - [email protected]; Bryan T Eaton - [email protected]; Christopher C Broder* - [email protected] * Corresponding author †Equal contributors Published: 18 July 2005 Received: 24 May 2005 Accepted: 18 July 2005 Virology Journal 2005, 2:57 doi:10.1186/1743-422X-2-57 This article is available from: http://www.virologyj.com/content/2/1/57 © 2005 Bossart et al; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. ParamyxovirusHendra virusNipah virusenvelope glycoproteinfusioninfectioninhibitionantiviral therapies Abstract Background: The recent emergence of four new members of the paramyxovirus family has heightened the awareness of and re-energized research on new and emerging diseases. In particular, the high mortality and person to person transmission associated with the most recent Nipah virus outbreaks, as well as the very recent re-emergence of Hendra virus, has confirmed the importance of developing effective therapeutic interventions. -

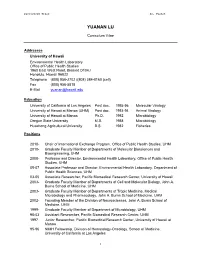

View Curriculum Vitae

Curriculum Vitae Lu, Yuanan YUANAN LU Curriculum Vitae Addresses University of Hawaii Environmental Health Laboratory Office of Public Health Studies 1960 East West Road, Biomed D104J Honolulu, Hawaii 96822 Telephone (808) 956-2702 /(808) 384-8160 (cell) Fax (808) 956-5818 E-Mail [email protected] Education University of California at Los Angeles Post doc. 1995-96 Molecular Virology University of Hawaii at Manoa (UHM) Post doc. 1993-94 Animal Virology University of Hawaii at Manoa Ph.D. 1992 Microbiology Oregon State University M.S. 1988 Microbiology Huazhong Agricultural University B.S. 1982 Fisheries Positions 2010- Chair of International Exchange Program, Office of Public Health Studies, UHM 2010- Graduate Faculty Member of Departments of Molecular Biosciences and Bioengineering, UHM 2008- Professor and Director, Environmental Health Laboratory, Office of Public Health Studies, UHM 05-07 Associate Professor and Director, Environmental Health Laboratory, Department of Public Health Sciences, UHM 03-05 Associate Researcher, Pacific Biomedical Research Center, University of Hawaii 2003- Graduate Faculty Member of Departments of Cell and Molecular Biology, John A. Burns School of Medicine, UHM 2003- Graduate Faculty Member of Departments of Tropic Medicine, Medical Microbiology and Pharmacology, John A. Burns School of Medicine, UHM 2002- Founding Member of the Division of Neurosciences, John A. Burns School of Medicine, UHM 1999- Graduate Faculty Member of Department of Microbiology, UHM 98-03 Assistant Researcher, Pacific Biomedical Research -

View Policy Viral Infectivity

Virology Journal BioMed Central Editorial Open Access Virology on the Internet: the time is right for a new journal Robert F Garry* Address: Department of Microbiology and Immunology Tulane University School of Medicine New Orleans, Louisiana USA Email: Robert F Garry* - [email protected] * Corresponding author Published: 26 August 2004 Received: 31 July 2004 Accepted: 26 August 2004 Virology Journal 2004, 1:1 doi:10.1186/1743-422X-1-1 This article is available from: http://www.virologyj.com/content/1/1/1 © 2004 Garry; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Abstract Virology Journal is an exclusively on-line, Open Access journal devoted to the presentation of high- quality original research concerning human, animal, plant, insect bacterial, and fungal viruses. Virology Journal will establish a strategic alternative to the traditional virology communication process. The outbreaks of SARS coronavirus and West Nile virus Open Access (WNV), and the troubling increase of poliovirus infec- Virology Journal's Open Access policy changes the way in tions in Africa, are but a few recent examples of the unpre- which articles in virology can be published [1]. First, all dictable and ever-changing topography of the field of articles are freely and universally accessible online as soon virology. Previously unknown viruses, such as the SARS as they are published, so an author's work can be read by coronavirus, may emerge at anytime, anywhere in the anyone at no cost. -

View of "Bird Flu: a Virus of Our Own Hatching" by Michael Greger Chengfeng Qin* and Ede Qin

Virology Journal BioMed Central Book report Open Access Review of "Bird Flu: A Virus of Our Own Hatching" by Michael Greger Chengfeng Qin* and Ede Qin Address: State Key Laboratory of Pathogen and Biosecurity, Institute of Microbiology and Epidemiology, Beijing 100071, China Email: Chengfeng Qin* - [email protected]; Ede Qin - [email protected] * Corresponding author Published: 30 April 2007 Received: 2 February 2007 Accepted: 30 April 2007 Virology Journal 2007, 4:38 doi:10.1186/1743-422X-4-38 This article is available from: http://www.virologyj.com/content/4/1/38 © 2007 Qin and Qin; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Book details behavior can cause new plagues, changes in human Michael Greger: Bird Flu: A Virus of Our Own Hatching USA: behavior may prevent them in the future". Lantern Books; 2006:465. ISBN 1590560981 Review Yes, we can change. In the last sections of the book, Greger Due to my responsibility as member of advisory commit- carefully details how to protect ourselves in the very likely tee on pandemic influenza, I regard any new publication event that a bird flu pandemic begins to sweep the world on bird flu with special enthusiasm. A book that recently and how to prevent future pandemics. Dr. Greger's simple caught my eye was one by Michael Greger titled Bird Flu: and practical suggestions are invaluable for both nation A Virus of Our Own Hatching. -

Isolation and Complete Genomic Characterization of H1N1 Subtype

Liu et al. Virology Journal 2011, 8:129 http://www.virologyj.com/content/8/1/129 RESEARCH Open Access Isolation and complete genomic characterization of H1N1 subtype swine influenza viruses in southern China through the 2009 pandemic Yizhi Liu1†, Jun Ji1†, Qingmei Xie1*, Jing Wang1, Huiqin Shang1, Cuiying Chen1, Feng Chen1,2, Chunyi Xue3, Yongchang Cao3, Jingyun Ma1, Yingzuo Bi1 Abstract Background: The swine influenza (SI) is an infectious disease of swine and human. The novel swine-origin influenza A (H1N1) that emerged from April 2009 in Mexico spread rapidly and caused a human pandemic globally. To determine whether the tremendous virus had existed in or transmitted to pigs in southern China, eight H1N1 influenza strains were identified from pigs of Guangdong province during 2008-2009. Results: Based on the homology and phylogenetic analyses of the nucleotide sequences of each gene segments, the isolates were confirmed to belong to the classical SI group, with HA, NP and NS most similar to 2009 human- like H1N1 influenza virus lineages. All of the eight strains were low pathogenic influenza viruses, had the same host range, and not sensitive to class of antiviral drugs. Conclusions: This study provides the evidence that there is no 2009 H1N1-like virus emerged in southern China, but the importance of swine influenza virus surveillance in China should be given a high priority. Background circulating in the swine population throughout the Swine influenza (SI) is an acute respiratory disease world currently [4,5]. caused by influenza A virus, a member of the Orthomyx- Pigs have the susceptibility of infecting avian and oviridae family. -

Virology Journal Biomed Central

Virology Journal BioMed Central Short report Open Access Genomic presence of recombinant porcine endogenous retrovirus in transmitting miniature swine Stanley I Martin, Robert Wilkinson and Jay A Fishman* Address: Infectious Disease Division, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA 02114, USA Email: Stanley I Martin - [email protected]; Robert Wilkinson - [email protected]; Jay A Fishman* - [email protected] * Corresponding author Published: 02 November 2006 Received: 22 June 2006 Accepted: 02 November 2006 Virology Journal 2006, 3:91 doi:10.1186/1743-422X-3-91 This article is available from: http://www.virologyj.com/content/3/1/91 © 2006 Martin et al; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Abstract The replication of porcine endogenous retrovirus (PERV) in human cell lines suggests a potential infectious risk in xenotransplantation. PERV isolated from human cells following cocultivation with porcine peripheral blood mononuclear cells is a recombinant of PERV-A and PERV-C. We describe two different recombinant PERV-AC sequences in the cellular DNA of some transmitting miniature swine. This is the first evidence of PERV-AC recombinant virus in porcine genomic DNA that may have resulted from autoinfection following exogenous viral recombination. Infectious risk in xenotransplantation will be defined by the activity of PERV loci in vivo. Background been detected previously in the genomes of transmitting Xenotransplantation using inbred miniature swine is a swine [5,10]. -

Journal of General and Molecular Virology

OPEN ACCESS Journal of General and Molecular Virology December 2018 ISSN 2141-6648 DOI: 10.5897/JGMV www.academicjournals.org About JGMV Journal of General and Molecular Virology (JGMV) is a peer reviewed journal. The journal is published per article and covers all areas of the subject such as: Isolation of chikungunya virus from non-human primates, Functional analysis of Lassa virus glycoprotein from a newly identified Lassa virus strain for possible use as vaccine using computational methods, as well as Molecular approaches towards analyzing the viruses infecting maize. JGMV welcomes the submission of manuscripts. Manuscripts should be submitted online via the Academic Journals Manuscript Management System. Indexing The Journal of General and Molecular Virology is indexed in Chemical Abstracts (CAS Source Index) and Dimensions Database Open Access Policy Open Access is a publication model that enables the dissemination of research articles to the global community without restriction through the internet. All articles published under open access can be accessed by anyone with internet connection. The Journal of General and Molecular Virology is an Open Access journal. Abstracts and full texts of all articles published in this journal are freely accessible to everyone immediately after publication without any form of restriction. Article License All articles published by Journal of General and Molecular Virology are licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. This permits anyone to copy, redistribute, remix, -

A Bibliometric Analysis of Virology in Colombia (2000–2013)

Original Article Virology research in a Latin American developing country: a bibliometric analysis of virology in Colombia (2000–2013) Julian Ruiz-Saenz1,3, Marlen Martinez-Gutierrez1,2,3 1 Grupo de Investigación en Ciencias Animales-GRICA, Facultad de Medicina Veterinaria y Zootecnia, Universidad Cooperativa de Colombia, Bucaramanga, Colombia 2 Grupo de Investigación Infettare, Facultad de Medicina, Universidad Cooperativa de Colombia, Medellín, Colombia 3 Asociación Colombiana de Virología, Bogotá, Colombia Abstract Introduction: Bibliometric analysis demonstrates that the virology research in Latin America has increased. For this reason, the objective of this study was to evaluate Colombian publications on viruses and viral diseases in indexed journals during the period from 2000 to 2013. Methodology: The bibliographic data were collected from MedLine, SciELO, LILACS and Scopus databases. The database was constructed in Excel descriptive statistics. The SCImago Journal Rank (SJR) was evaluated using the SCImago Journal & Country Rank in 2013 and was used as an indicator of the quality of the journals used by the Colombian researchers. Results: The total number of papers published was 711, of which 40.4% were published in local journals, and 59.6% were published in foreign journals. Most (89.2%) were original papers. Moreover, 34.2% of the papers were published in collaboration with international researchers, with the United States being the most represented. Of the journals used, 85.6% had an SJR, and 14.4% did not. The median SJR of the papers was 0.789, and the median of the papers with international collaborators was higher compared to the SJR of the papers without international collaboration. -

Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus: an Emerging and Re-Emerging Epizootic Swine Virus Changhee Lee

Lee Virology Journal (2015) 12:193 DOI 10.1186/s12985-015-0421-2 REVIEW Open Access Porcine epidemic diarrhea virus: An emerging and re-emerging epizootic swine virus Changhee Lee Abstract The enteric disease of swine recognized in the early 1970s in Europe was initially described as “epidemic viral diarrhea” and is now termed “porcine epidemic diarrhea (PED)”. The coronavirus referred to as PED virus (PEDV) was determined to be the etiologic agent of this disease in the late 1970s. Since then the disease has been reported in Europe and Asia, but the most severe outbreaks have occurred predominantly in Asian swine-producing countries. Most recently, PED first emerged in early 2013 in the United States that caused high morbidity and mortality associated with PED, remarkably affecting US pig production, and spread further to Canada and Mexico. Soon thereafter, large-scale PED epidemics recurred through the pork industry in South Korea, Japan, and Taiwan. These recent outbreaks and global re-emergence of PED require urgent attention and deeper understanding of PEDV biology and pathogenic mechanisms. This paper highlights the current knowledge of molecular epidemiology, diagnosis, and pathogenesis of PEDV, as well as prevention and control measures against PEDV infection. More information about the virus and the disease is still necessary for the development of effective vaccines and control strategies. It is hoped that this review will stimulate further basic and applied studies and encourage collaboration among producers, researchers, and swine veterinarians to provide answers that improve our understanding of PEDV and PED in an effort to eliminate this economically significant viral disease, which emerged or re-emerged worldwide. -

View of the Manuscript

Virology Journal BioMed Central Research Open Access Vaccinia virus lacking the deoxyuridine triphosphatase gene (F2L) replicates well in vitro and in vivo, but is hypersensitive to the antiviral drug (N)-methanocarbathymidine Mark N Prichard*1, Earl R Kern1, Debra C Quenelle1, Kathy A Keith1, Richard W Moyer2 and Peter C Turner2 Address: 1Department of Pediatrics, University of Alabama School of Medicine, Birmingham, AL 35233, USA and 2Department of Molecular Genetics and Microbiology, University of Florida College of Medicine, Gainesville, FL 32610, USA Email: Mark N Prichard* - [email protected]; Earl R Kern - [email protected]; Debra C Quenelle - [email protected]; Kathy A Keith - [email protected]; Richard W Moyer - [email protected]; Peter C Turner - [email protected] * Corresponding author Published: 5 March 2008 Received: 24 January 2008 Accepted: 5 March 2008 Virology Journal 2008, 5:39 doi:10.1186/1743-422X-5-39 This article is available from: http://www.virologyj.com/content/5/1/39 © 2008 Prichard et al; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Abstract Background: The vaccinia virus (VV) F2L gene encodes a functional deoxyuridine triphosphatase (dUTPase) that catalyzes the conversion of dUTP to dUMP and is thought to minimize the incorporation of deoxyuridine residues into the viral genome. Previous studies with with a complex, multigene deletion in this virus suggested that the gene was not required for viral replication, but the impact of deleting this gene alone has not been determined in vitro or in vivo. -

Oxygen: Viral Friend Or Foe? Esther Shuyi Gan1* and Eng Eong Ooi1,2,3

Gan and Ooi Virology Journal (2020) 17:115 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12985-020-01374-2 REVIEW Open Access Oxygen: viral friend or foe? Esther Shuyi Gan1* and Eng Eong Ooi1,2,3 Abstract The oxygen levels organ and tissue microenvironments vary depending on the distance of their vasculature from the left ventricle of the heart. For instance, the oxygen levels of lymph nodes and the spleen are significantly lower than that in atmospheric air. Cellular detection of oxygen and their response to low oxygen levels can exert a significant impact on virus infection. Generally, viruses that naturally infect well-oxygenated organs are less able to infect cells under hypoxic conditions. Conversely, viruses that infect organs under lower oxygen tensions thrive under hypoxic conditions. This suggests that in vitro experiments performed exclusively under atmospheric conditions ignores oxygen-induced modifications in both host and viral responses. Here, we review the mechanisms of how cells adapt to low oxygen tensions and its impact on viral infections. With growing evidence supporting the role of oxygen microenvironments in viral infections, this review highlights the importance of factoring oxygen concentrations into in vitro assay conditions. Bridging the gap between in vitro and in vivo oxygen tensions would allow for more physiologically representative insights into viral pathogenesis. Keywords: Hypoxia, Viruses Background viruses that naturally infect and replicate in tissues with Viral infections are heavily dependent on host cells for high oxygen content are impaired by hypoxic environ- energy, enzymes and metabolic intermediates for suc- ments. Conversely, hypoxia has been shown to increase cessful replication [134].