Corruption As a Legacy of the Medieval University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Linus J. Guillory Jr., Phd, Chief Schools Officer DATE

Linus J. Guillory Jr., PhD LOWELL PUBLIC SCHOOLS Chief Schools Officer Phone: (978) 674-2163 155 Merrimack Street E-mail: [email protected] Lowell, Massachusetts 01852 TO: Dr. Joel Boyd, Superintendent of Schools FROM: Linus J. Guillory Jr., PhD, Chief Schools Officer DATE: September 27, 2019 RE: Update on the Latin Lyceum The following report is in response to a motion by Gerard Nutter & Andy Descoteaux: Administration to explain the change in philosophy regarding class location for the Latin Lyceum and Freshman Academy. Robert DeLossa prepared a response for Head of Lowell High School Busteed. The entirety of the response is reflected herein. From: Robert DeLossa To: Marianne Busteed Date: 25 September 2019 RE: Response to School Committee Motion with regard to the change of Freshman location to FA for Lyceum Students With regard to the question of whether the decision to house the teachers of Freshman Lyceum students in the Freshman Academy reflected a change of philosophy underlying the Lowell Latin Lyceum, I can state categorically that it did not. The underlying philosophy of the LLL remains the same as it has since the beginning of the Lyceum. Below I will point to two different areas to consider. The first is that the move to the Freshman Academy actually is more consistent with the philosophy of the Lyceum than the previous arrangement. Second, the move to the Freshman Academy better supports the individual needs of Lyceum students, who because of their academic giftedness and creativity, often need more social-emotional support than the previous arrangement provided. That support is physically located in the Freshman Academy. -

One, Holy, Catholic, and Apostolic: a History of the Church in the Middle Ages

ONE , H OLY , CATHOLIC , AND APOSTOLIC : A H ISTORY OF THE CHURCH IN THE MIDDLE AGES COURSE GUIDE Professor Thomas F. Madden SAINT LOUIS UNIVERSITY One, Holy, Catholic, and Apostolic: A History of the Church in the Middle Ages Professor Thomas F. Madden Saint Louis University Recorded Books ™ is a trademark of Recorded Books, LLC. All rights reserved. One, Holy, Catholic, and Apostolic: A History of the Church in the Middle Ages Professor Thomas F. Madden Executive Producer John J. Alexander Executive Editor Donna F. Carnahan RECORDING Producer - David Markowitz Director - Matthew Cavnar COURSE GUIDE Editor - James Gallagher Contributing Editor - Karen Sparrough Design - Edward White Lecture content ©2006 by Thomas F. Madden Course guide ©2006 by Recorded Books, LLC 72006 by Recorded Books, LLC Cover image: Basilica of Notre Dame Cathedral, Paris © Clipart.com #UT095 ISBN: 978-1-4281-3777-6 All beliefs and opinions expressed in this audio/video program and accompanying course guide are those of the author and not of Recorded Books, LLC, or its employees. Course Syllabus One, Holy, Catholic, and Apostolic: A History of the Church in the Middle Ages About Your Professor ................................................................................................... 4 Introduction ................................................................................................................... 5 Lecture 1 Birth of the Medieval Church ................................................................. 6 Lecture 2 The Church in an Age of -

Partner Schools Art & Design

Art&Design Partner Institutions Erasmus Code Country City Institute A LINZ02 Austria Linz University of Art and Design A WIEN07 Austria Vienna University of Applied Arts Vienna ARTESIS PLANTIJN HOGESCHOOL B ANTWERP62 Belgium Antwerpen ANTWERPEN Brugge / Vives Katholieke Hogeschool Brugge - B BRUGGE11 Belgium Oostende Oostende B BRUSSEL43 Belgium Brussels/Ghent LUCA ( vroeger Hogeschool Sint-Lukas Brussel) B GENT25 Belgium Ghent Hogeschool Gent, School of Arts – KASK B HASSELT22 Belgium Hasselt PIXL University College Film and tv school of Academy of performing CZ PRAHA04 Czech Republic Prague arts in Prague (FAMU) D BRAUNSC02 Germany Braunschweig Hochschule für Bildende Künste Braunschweig D DUSSELD03 Germany Dusseldorf Fachhochschule Düsseldorf D HALLE03 Germany Halle Burg Giebichenstein Kunsthochschule Halle Staatliche Hochschule fur Gestaltung D KARLSRU06 Germany Karlsruhe Karlsruhe D KOBLENZ01 Germany Koblenz UNIVERSITY OF APPLIED SCIENCES KOBLENZ D MAINZ08 Germany Mainz Fachhochschule Mainz Schwäbisch D SCHWA02 Germany Hochschule für Gestaltung Schwäbisch Gmünd Gmünd D TRIER02 Germany Trier Hochschule Trier DK Denmark Kopenhagen Danmarks Designskole KOBENHA59 DK Denmark Kolding Kolding School of Design KOLDING07 E BARCELO02 Spain Barcelona Escola Massana Centre d'Art i Disseny E CIUDAR 01 Spain Cuenca Universidad de Castilla la Mancha (UCLM) Version January 2020 E MADRID03 Spain Madrid Universidad Complutense de Madrid E MADRID197 Spain Madrid Centro Universitario de Artes TAI La Escola d'Art i Superior de Disseny de E VALENCI13 Spain -

Teacher Education Policies and Programs in Pakistan

TEACHER EDUCATION POLICIES AND PROGRAMS IN PAKISTAN: THE GROWTH OF MARKET APPROACHES AND THEIR IMPACT ON THE IMPLEMENTATION AND THE EFFECTIVENESS OF TRADITIONAL TEACHER EDUCATION PROGRAMS By Fida Hussain Chang A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Curriculum, Instruction, and Teacher Education - Doctor of Philosophy 2014 ABSTRACT TEACHER EDUCATION POLICIES AND PROGRAMS IN PAKISTAN: THE GROWTH OF MARKET APPROACHES AND THEIR IMPACT ON THE IMPLEMENTATION AND THE EFFECTIVENESS OF TRADITIONAL TEACHER EDUCATION PROGRAMS By Fida Hussain Chang Two significant effects of globalization around the world are the decentralization and liberalization of systems, including education services. In 2000, the Pakistani Government brought major higher education liberalization and expansion reforms by encouraging market approaches based on self-financed programs. These approaches have been particularly important in the area of teacher education and development. The Pakistani Government data reports (AEPAM Islamabad) on education show vast growth in market-model off-campus (open and distance) post-baccalaureate teacher education programs in the last fifteen years. Many academics and scholars have criticized traditional off-campus programs for their low quality; new policy reforms in 2009, with the support of USAID, initiated the four-year honors program, with the intention of phasing out all traditional programs by 2018. However, the new policy still allows traditional off-campus market-model programs to be offered. This important policy reform juncture warrants empirical research on the effectiveness of traditional programs to inform current and future policies. Thus, this study focused on assessing the worth of traditional and off-campus programs, and the effects of market approaches, on the implementation of traditional post-baccalaureate teacher education programs offered by public institutions in a southern province of Pakistan. -

Liberal Arts Colleges in American Higher Education

Liberal Arts Colleges in American Higher Education: Challenges and Opportunities American Council of Learned Societies ACLS OCCASIONAL PAPER, No. 59 In Memory of Christina Elliott Sorum 1944-2005 Copyright © 2005 American Council of Learned Societies Contents Introduction iii Pauline Yu Prologue 1 The Liberal Arts College: Identity, Variety, Destiny Francis Oakley I. The Past 15 The Liberal Arts Mission in Historical Context 15 Balancing Hopes and Limits in the Liberal Arts College 16 Helen Lefkowitz Horowitz The Problem of Mission: A Brief Survey of the Changing 26 Mission of the Liberal Arts Christina Elliott Sorum Response 40 Stephen Fix II. The Present 47 Economic Pressures 49 The Economic Challenges of Liberal Arts Colleges 50 Lucie Lapovsky Discounts and Spending at the Leading Liberal Arts Colleges 70 Roger T. Kaufman Response 80 Michael S. McPherson Teaching, Research, and Professional Life 87 Scholars and Teachers Revisited: In Continued Defense 88 of College Faculty Who Publish Robert A. McCaughey Beyond the Circle: Challenges and Opportunities 98 for the Contemporary Liberal Arts Teacher-Scholar Kimberly Benston Response 113 Kenneth P. Ruscio iii Liberal Arts Colleges in American Higher Education II. The Present (cont'd) Educational Goals and Student Achievement 121 Built To Engage: Liberal Arts Colleges and 122 Effective Educational Practice George D. Kuh Selective and Non-Selective Alike: An Argument 151 for the Superior Educational Effectiveness of Smaller Liberal Arts Colleges Richard Ekman Response 172 Mitchell J. Chang III. The Future 177 Five Presidents on the Challenges Lying Ahead The Challenges Facing Public Liberal Arts Colleges 178 Mary K. Grant The Importance of Institutional Culture 188 Stephen R. -

Science and Nature in the Medieval Ecological Imagination Jessica Rezunyk Washington University in St

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations Arts & Sciences Winter 12-15-2015 Science and Nature in the Medieval Ecological Imagination Jessica Rezunyk Washington University in St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/art_sci_etds Recommended Citation Rezunyk, Jessica, "Science and Nature in the Medieval Ecological Imagination" (2015). Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 677. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/art_sci_etds/677 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Arts & Sciences at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY IN ST. LOUIS Department of English Dissertation Examination Committee: David Lawton, Chair Ruth Evans Joseph Loewenstein Steven Meyer Jessica Rosenfeld Science and Nature in the Medieval Ecological Imagination by Jessica Rezunyk A dissertation presented to the Graduate School of Arts & Sciences of Washington University in partial fulfillment of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2015 St. Louis, Missouri © 2015, Jessica Rezunyk Table of Contents List of Figures……………………………………………………………………………. iii Acknowledgments…………………………………………………………………………iv Abstract……………………………………………………………………………………vii Chapter 1: (Re)Defining -

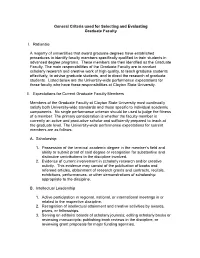

General Criteria Used for Selecting and Evaluating Graduate Faculty I

General Criteria used for Selecting and Evaluating Graduate Faculty I. Rationale A majority of universities that award graduate degrees have established procedures to identify faculty members specifically qualified to train students in advanced degree programs. These members are then identified as the Graduate Faculty. The main responsibilities of the Graduate Faculty are to conduct scholarly research and creative work of high quality, to teach graduate students effectively, to advise graduate students, and to direct the research of graduate students. Listed below are the University-wide performance expectations for those faculty who have these responsibilities at Clayton State University. II. Expectations for Current Graduate Faculty Members Members of the Graduate Faculty at Clayton State University must continually satisfy both University-wide standards and those specific to individual academic components. No single performance criterion should be used to judge the fitness of a member. The primary consideration is whether the faculty member is currently an active and productive scholar and sufficiently prepared to teach at the graduate level. The University-wide performance expectations for current members are as follows: A. Scholarship 1. Possession of the terminal academic degree in the member’s field and ability to submit proof of said degree or recognition for substantive and distinctive contributions to the discipline involved. 2. Evidence of current involvement in scholarly research and/or creative activity. This evidence may consist of the publication of books and refereed articles, obtainment of research grants and contracts, recitals, exhibitions, performances, or other demonstrations of scholarship appropriate to the discipline. B. Intellectual Leadership 1. Active participation in regional, national, or international meetings in or related to the respective discipline. -

Decoding the Statutes of Gregory IX for the University of Paris 1231

Decoding The Statutes of Gregory IX for the University of Paris 1231 What had motivated Gregory IX's interest in the University of Paris? The Statutes of Gregory IX 1 for the University of Paris 1231 2 define the new rights and privileges of the teachers and students and help stopping the exodus of the teachers and students from the University, particularly for Oxford. It serves to ratify with immediacy as per a perceived denial 3 of justice, which had been sanctioned by Queen Blanche in 1229 and resulted in the teachers’ 2-year suspension of their teaching for the courses in retaliation. 4 Well-versed in the political situation of Europe 5, Pope Gregory IX’s 6 worries seem well-founded an exodus of teachers and students from The University of Paris does happen before the enactment of The Statutes. The teacher-student exodus in Europe has always been a widespread phenomenon.7 Gregory XI’s bestow on students’ right and privileges may well be his being a past student of The University of Paris, but his strong stance in anti-hereticism might point to his intended control over the teachers and students 8 carries much water. While no ulterior motive could justly be implied to Gregory IX, as a nephew of the 1 Based on the translation from Dana C. Munro, trans., University of Pennsylvania Translations and Reprints , (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1897), Vol. II: No. 3, pp. 7-11 2 Hereafter called The Statutes. 3 The trouble originated in a quarrel in an inn in Paris which developed into a fight between the students and the citizens of Paris. -

Erasmus + Agreement

Annex to Erasmus+ Inter-Institutional Agreement Institutional Factsheet 1. Institutional Information 1.1. Institutional details Name of the institution Université Paris Diderot – Paris 7 Erasmus Code F PARIS007 EUC Nr. 28258 Institution website http://www.univ-paris-diderot.fr Online course catalogue / 1.2. Main contacts Contact person Jan DOUAT* Responsibility Central management of the Erasmus+ program Contact person for Erasmus+ partners Contact details Phone: +33 1 57 27 59 53 - Fax: +33 1 57 27 55 07 Email: [email protected] Contact person Floriane THOREZ* Responsibility Contact person for incoming students / Internships Contact details Phone: +33 1 57 27 55 05 - Fax: +33 1 57 27 55 07 - Email: [email protected] Contact person Valérie BEAUDOIN* Responsibility Contact person for outgoing students Contact details Phone: +33 1 57 27 55 34 - Fax: +33 1 57 27 55 07 - Email: [email protected] The email address will remain identical even in the case of a turnover Annex to Erasmus + Inter-Institutional Agreement | Institutional Factsheet Page 1 / 4 2. Detailed requirements and additional information 2.1. Recommended language skills Following agreement with our institution, the sending institution is responsible for providing support to its nominated candidates so that they can have the recommended language skills at the start of the study or teaching period: COURSES ARE TAUGHT IN FRENCH Type of mobility Subject area Language(s) of instruction Recommended language of instruction -

Curriculum Vitae Voula Tsouna

1 Curriculum Vitae Voula Tsouna Department of Philosophy, University of California Santa Barbara, CA 93106-3090 [email protected] Place of Birth: Athens, Greece Nationality: Greek (EU) & USA Languages: Ancient Greek, Latin, French (fluent), English (fluent), Modern Greek (fluent), Italian (competent), German (reading) AREA OF SPECIALIZATION Ancient Philosophy AREAS OF COMPETENCE Siècle des Lumières (French Enlightment), Early Modern Philosophy, topics in Epistemology, Moral Psychology, and Ethics. EDUCATION 1988 PhD (Thèse de doctorat), Ancient Philosophy, University of Paris X 1984-86 Doctoral Research, fully enrolled graduate student at the University of Cambridge, King’s College 1984 Diplôme d’Études Approfondies (DEA, equivalent to the MA), Ancient Philosophy, University of Paris X 1983 Bachelor of Arts in Philosophy summa cum laude (Πτυχεῖον summa cum laude), Philosophy, University of Athens ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS 2006–present University of California at Santa Barbara, Full Professor 2000–2006 University of California at Santa Barbara, Associate Professor 1997–2000 University of California at Santa Barbara, Assistant Professor 1997 (Winter) University of California at Santa Barbara, Visiting Assistant Professor of Philosophy 2010 (Spring) University of Crete, Holder of the Michelis Chair in Aesthetics at the Department of Philosophy and Social Studies 1994–1996 Pomona College, Visiting Assistant Professor 1992–1993 University of Glasgow, Scotland, Research Fellow 1991–1992 California State University at San Bernardino, Lecturer -

Liberal Arts Education and Information Technology

VIEWPOINT Liberal Arts Education and Information Technology: Time for Another Renewal Liberal arts colleges must accommodate the powerful changes that are taking place in the way people communicate and learn by Todd D. Kelley hree significant societal trends and that institutional planning and deci- Five principal reasons why the future will most certainly have a broad sion making must reflect the realities of success of liberal arts colleges is tied to Timpact on information services rapidly changing information technol- their effective use of information tech- and higher education for some time to ogy. Boards of trustees and senior man- nology are: come: agement must not delay in examining • Liberal arts colleges have an obliga- • the increasing use of information how these changes in society will impact tion to prepare their students for life- technology (IT) for worldwide com- their institutions, both negatively and long learning and for the leadership munications and information cre- positively, and in embracing the idea roles they will assume when they ation, storage, and retrieval; that IT is integral to fulfilling their liberal graduate. • the continuing rapid change in the arts missions in the future. • Liberal arts colleges must demon- development, maturity, and uses of (2) To plan and support technological strate the use of the most significant information technology itself; and change effectively, their colleges must approaches to problem solving and • the growing need in society for have sufficient high-quality information communications to have emerged skilled workers who can understand services staff and must take a flexible and since the invention of the printing and take advantage of the new meth- creative approach to recruiting and press and movable type. -

Dr. Jeffrey Dirk Wilson CV

Photo credit: Robert M. West Jeffrey Dirk Wilson “For natures such as mine, a journey is invaluable: it enlivens, corrects, teaches, and cultivates.” Johann Wolfgang von Goethe 1 Jeffrey Dirk Wilson: CV—May 20, 2021 With tomatoes on my right, cucumbers on my left, and apples behind me. “The greatest service which can be rendered any country is to add an useful plant to its culture.” Thomas Jefferson 2 Jeffrey Dirk Wilson: CV—May 20, 2021 Jeffrey Dirk Wilson 103c Aquinas Hall School of Philosophy The Catholic University of America 410.452.8465 [email protected] ______________________________________________________________________________ Areas of Specialization: Areas of Competence: Ancient Greek Philosophy Art and Language Classical Metaphysics Epistemology Political Philosophy Ethics Human Nature Academic Experience: Collegiate Associate Professor (formerly Clinical Associate Professor), The School of Philosophy of the Catholic University of America; courses taught: “The Classical Mind,” “The Modern Mind,” “Metaphysics,” “Philosophy of Art” “Philosophy of Knowledge,” “Philosophy of Human Nature,” “Philosophy of Natural Right and Natural Law,” “Political Philosophy,” “Philosophy of Language” “Senior Seminar: The Metaphysics of Beauty”: 2015-present. Non-Residential Fellow, Instituto de Filosofía Edith Stein: 2021-present. Clinical Assistant Professor, The School of Philosophy of The Catholic University of America: 2009-2015. Adjunct Clinical Assistant Professor, St. Mary’s Seminary and University, School of Theology; course taught: “Metaphysics”: winter-spring 2013. Lecturer (full-time), Mount St. Mary’s University, Emmitsburg, Maryland; courses taught: “From Cosmos to Citizen,” “From Self to Society,” “Moral Philosophy”: 2007-2009. Lecturer, The School of Philosophy, The Catholic University of America, Washington, D.C.; courses taught: “The Classical Mind,” “The Modern Mind”: 2005-2006, fall 2006.” Member of the Library Committee for the School of Philosophy, The Catholic University of America, Washington, D.C.: 2005-2006.