The Man Who Disappeared

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Scope of Police Questioning During a Routine Traffic Stop: Do

Fordham Urban Law Journal Volume 30 | Number 6 Article 3 2003 The copS e of Police Questioning During a Routine Traffict S op: Do Questions Outside the Scope of the Original Justification for the Stop Create Impermissible Seizures If They Do Not Prolong the Stop? Bill Lawrence Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ulj Part of the Constitutional Law Commons Recommended Citation Bill Lawrence, The Scope of Police Questioning During a Routine Traffict S op: Do Questions Outside the Scope of the Original Justification for the Stop Create Impermissible Seizures If They Do Not Prolong the Stop? , 30 Fordham Urb. L.J. 1919 (2003). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ulj/vol30/iss6/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The orF dham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Urban Law Journal by an authorized editor of FLASH: The orF dham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The copS e of Police Questioning During a Routine Traffict S op: Do Questions Outside the Scope of the Original Justification for the Stop Create Impermissible Seizures If They Do Not Prolong the Stop? Cover Page Footnote J.D. candidate, Fordham University School of Law, 2004; B.A., Communication, Villanova University, 2000. I would like to thank my family and friends for their love and support. I also sincerely thank Professor Daniel Richman for his valuable insights. This article is available in Fordham -

When Can You Be Ticketed for Driving Without a License?

WHEN CAN YOU BE TICKETED FOR DRIVING WITHOUT A LICENSE? LAW: “No person, except those expressly exempted, shall drive any motor vehicle upon a highway or public property in this Commonwealth unless the person has a driver's license valid under the provisions of this chapter.” “Public property” only includes parking lots owned or leased by the Commonwealth. 75 Pa. Cons. Stat. § 1501(a). MEANING: Based on the language of the statute, you cannot be cited for driving without a license while only in the Home Depot parking lot because it is not a public highway. DEFENSE: If you were cited for driving without a license in the parking lot you should request a hearing to dispute the ticket. At the hearing you could make a corpus delicti objection (principle that a crime must have been proven to have occurred before conviction). If asked how you arrived at the parking lot, you can invoke 5th amendment protection (against self-incrimination) to not respond. If the officer never observed you driving outside the lot, then you may prevail in disputing the ticket. TIP: If you are stopped in the parking lot the officer could ask you how you got to the parking lot. You should not answer that question. BUT WHAT ABOUT PROBABLE CAUSE? CAN THE POLICE STOP ME WHENEVER THEY WANT? No, the police need probable cause to stop you in your car. There is no probable cause for stopping a driver for driving without a license. Therefore, unless there is another reason to stop a vehicle, such as expired registration, or speeding, there should not be a traffic stop. -

“In the Mood”—Glenn Miller (1939) Added to the National Recording Registry: 2004 Essay by Cary O’Dell

“In the Mood”—Glenn Miller (1939) Added to the National Recording Registry: 2004 Essay by Cary O’Dell Glenn Miller Original release label “Sun Valley Serenade” Though Glenn Miller and His Orchestra’s well-known, robust and swinging hit “In the Mood” was recorded in 1939 (and was written even earlier), it has since come to symbolize the 1940s, World War II, and the entire Big Band Era. Its resounding success—becoming a hit twice, once in 1940 and again in 1943—and its frequent reprisal by other artists has solidified it as a time- traversing classic. Covered innumerable times, “In the Mood” has endured in two versions, its original instrumental (the specific recording added to the Registry in 2004) and a version with lyrics. The music was written (or written down) by Joe Garland, a Tin Pan Alley tunesmith who also composed “Leap Frog” for Les Brown and his band. The lyrics are by Andy Razaf who would also contribute the words to “Ain’t Misbehavin’” and “Honeysuckle Rose.” For as much as it was an original work, “In the Mood” is also an amalgamation, a “mash-up” before the term was coined. It arrived at its creation via the mixture and integration of three or four different riffs from various earlier works. Its earliest elements can be found in “Clarinet Getaway,” from 1925, recorded by Jimmy O’Bryant, an Arkansas bandleader. For his Paramount label instrumental, O’Bryant was part of a four-person ensemble, featuring a clarinet (played by O’Bryant), a piano, coronet and washboard. Five years later, the jazz piece “Tar Paper Stomp” by Joseph “Wingy” Manone, from 1930, beget “In the Mood’s” signature musical phrase. -

Successfully Defending an OUI Case

CHAPTER 10 Successfully Defending an OUI Case David P. Sorrenti, Esq. Sorrenti & Delano, Brockton § 10.1 Introduction ............................................................................... 10–1 § 10.2 The Offense ................................................................................ 10–2 § 10.3 Operation ................................................................................... 10–2 § 10.3.1 Definition .................................................................... 10–2 § 10.3.2 Defense ....................................................................... 10–3 § 10.4 Public Way .................................................................................. 10–4 § 10.4.1 Definition .................................................................... 10–4 § 10.4.2 Stipulation of Proof .................................................... 10–5 § 10.4.3 Defense ....................................................................... 10–5 § 10.5 Under the Influence ................................................................... 10–6 § 10.5.1 Diminished Capacity .................................................. 10–6 (a) General Principles ............................................. 10–6 (b) Opinion Evidence .............................................. 10–7 (c) Erratic Operation ............................................... 10–7 (d) Odor of Alcohol ................................................. 10–7 (e) Red or Glassy Eyes ............................................ 10–8 (f) Slurred Speech .................................................. -

If Approached Or Stopped by a Police Officer Traffic Stop

WHY DO POLICE STOP CITIZENS OR TRAFFIC STOP – WHAT TO DO POLICE AT YOUR HOME VEHICLES? Slow down and pull to the right, or onto a side Usually if a police officer knocks on your Person appears to need assistance street. door, it is for one of the these reasons: Traffic violation If you feel unsafe or suspect it’s not really the . To interview you or a member of your Person suspected of violating the law police, turn on your emergency flashers and household as a witness or a suspect to an Person fits the description of a suspect continue slowly to a well-lit location like a gas incident that is being investigated. To serve an arrest warrant Person has been pointed out as a suspect station. If still unsure, dial 9-1-1 to get confirmation. To serve a search warrant Person may have witnessed a crime If stopped at night, turn on the dome light. To make a notification Officer seeking information about a crime Spotlights and flashlights are used to If they are not in uniform, make sure they Officer is making a community contact illuminate the scene for everyone’s safety, not really are law enforcement officers by to intimidate you. requesting to see a badge and identification IF APPROACHED OR STOPPED BY A Do not exit your vehicle, but wait for the card. POLICE OFFICER officer. Whenever police come to your door, they Keep your hands where the officer can see Keeping your hands visible, such as on the should willingly provide identification and them and don’t put them in your pockets. -

Jazz Quartess Songlist Pop, Motown & Blues

JAZZ QUARTESS SONGLIST POP, MOTOWN & BLUES One Hundred Years A Thousand Years Overjoyed Ain't No Mountain High Enough Runaround Ain’t That Peculiar Same Old Song Ain’t Too Proud To Beg Sexual Healing B.B. King Medley Signed, Sealed, Delivered Boogie On Reggae Woman Soul Man Build Me Up Buttercup Stop In The Name Of Love Chasing Cars Stormy Monday Clocks Summer In The City Could It Be I’m Fallin’ In Love? Superstition Cruisin’ Sweet Home Chicago Dancing In The Streets Tears Of A Clown Everlasting Love (This Will Be) Time After Time Get Ready Saturday in the Park Gimme One Reason Signed, Sealed, Delivered Green Onions The Scientist Groovin' Up On The Roof Heard It Through The Grapevine Under The Boardwalk Hey, Bartender The Way You Do The Things You Do Hold On, I'm Coming Viva La Vida How Sweet It Is Waste Hungry Like the Wolf What's Going On? Count on Me When Love Comes To Town Dancing in the Moonlight Workin’ My Way Back To You Every Breath You Take You’re All I Need . Every Little Thing She Does Is Magic You’ve Got a Friend Everything Fire and Rain CONTEMPORARY BALLADS Get Lucky A Simple Song Hey, Soul Sister After All How Sweet It Is All I Do Human Nature All My Life I Believe All In Love Is Fair I Can’t Help It All The Man I Need I Can't Help Myself Always & Forever I Feel Good Amazed I Was Made To Love Her And I Love Her I Saw Her Standing There Baby, Come To Me I Wish Back To One If I Ain’t Got You Beautiful In My Eyes If You Really Love Me Beauty And The Beast I’ll Be Around Because You Love Me I’ll Take You There Betcha By Golly -

View the Full Song List

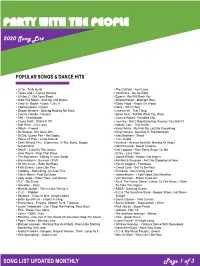

PARTY WITH THE PEOPLE 2020 Song List POPULAR SONGS & DANCE HITS ▪ Lizzo - Truth Hurts ▪ The Outfield - Your Love ▪ Tones And I - Dance Monkey ▪ Vanilla Ice - Ice Ice Baby ▪ Lil Nas X - Old Town Road ▪ Queen - We Will Rock You ▪ Walk The Moon - Shut Up And Dance ▪ Wilson Pickett - Midnight Hour ▪ Cardi B - Bodak Yellow, I Like It ▪ Eddie Floyd - Knock On Wood ▪ Chainsmokers - Closer ▪ Nelly - Hot In Here ▪ Shawn Mendes - Nothing Holding Me Back ▪ Lauryn Hill - That Thing ▪ Camila Cabello - Havana ▪ Spice Girls - Tell Me What You Want ▪ OMI - Cheerleader ▪ Guns & Roses - Paradise City ▪ Taylor Swift - Shake It Off ▪ Journey - Don’t Stop Believing, Anyway You Want It ▪ Daft Punk - Get Lucky ▪ Natalie Cole - This Will Be ▪ Pitbull - Fireball ▪ Barry White - My First My Last My Everything ▪ DJ Khaled - All I Do Is Win ▪ King Harvest - Dancing In The Moonlight ▪ Dr Dre, Queen Pen - No Diggity ▪ Isley Brothers - Shout ▪ House Of Pain - Jump Around ▪ 112 - Cupid ▪ Earth Wind & Fire - September, In The Stone, Boogie ▪ Tavares - Heaven Must Be Missing An Angel Wonderland ▪ Neil Diamond - Sweet Caroline ▪ DNCE - Cake By The Ocean ▪ Def Leppard - Pour Some Sugar On Me ▪ Liam Payne - Strip That Down ▪ O’Jay - Love Train ▪ The Romantics -Talking In Your Sleep ▪ Jackie Wilson - Higher And Higher ▪ Bryan Adams - Summer Of 69 ▪ Ashford & Simpson - Ain’t No Stopping Us Now ▪ Sir Mix-A-Lot – Baby Got Back ▪ Kenny Loggins - Footloose ▪ Faith Evans - Love Like This ▪ Cheryl Lynn - Got To Be Real ▪ Coldplay - Something Just Like This ▪ Emotions - Best Of My Love ▪ Calvin Harris - Feel So Close ▪ James Brown - I Feel Good, Sex Machine ▪ Lady Gaga - Poker Face, Just Dance ▪ Van Morrison - Brown Eyed Girl ▪ TLC - No Scrub ▪ Sly & The Family Stone - Dance To The Music, I Want ▪ Ginuwine - Pony To Take You Higher ▪ Montell Jordan - This Is How We Do It ▪ ABBA - Dancing Queen ▪ V.I.C. -

THE UTION and ~~X,Mt C',D,~N~'W of T~CHNOLOGY

THE UTION AND ~~x,mT c',D,~n~'w OF T~CHNOLOGY J S~SKATE, INC. THE EVOLUTION AND DEVELOPMENT OF POLICE TECHNOLOGY A Technical Report prepared for The National Committee on Criminal Justice Technology National Institute of Justice By SEASKATE, INC. 555 13th Street, NW 3rd Floor, West Tower Washington, DC 20004 July 1, 1998 This project was supported under Grant 95-IJ-CX-K001(S-3) from the National Institute of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice. Points of view in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the U.S. Department of Justice. PROPERTY OF National Criminal Justice Reference Service (NCJRSJ Box 6000 Rockville, MD 20849-6000~ ~ ...... 0 0 THE EVOLUTION AND DEVELOPMENT OF POLICE TECHNOLOGY THIS PUBLICATION CONTAINS BOTH AN OVERVIEW AND FULL-LENGTH VERSIONS OF OUR REPORT ON POLICE TECHNOLOGY. PUBLISHING THE TWO VERSIONS TOGETHER ACCOUNTS FOR SOME DUPLICATION OF TEXT. THE OVERVIEW IS DESIGNED TO BE A BRIEF SURVEY OF THE SUBJECT. THE TECHNICAL REPORT IS MEANT FOR READERS SEEKING DETAILED INFORMATION. o°° 111 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................. VI OVERVIEW REPORT INTRODUCTION ..............................................................1 PART ONE:THE HISTORY AND THE EMERGING FEDERAL ROLE ................................ 2 THE POLITICAL ERA ........................................................ 2 THE PROFESSIONALMODEL ERA ................................................ 2 TECHNOLOGY AND THE -

Implied Consent Laws Will Only Apply As Follows

IMPLIED CONSENT Why are we discussing Implied Consent? What does Implied Consent have to do with Intoxilyzer Operations? After stopping a motorist on suspicion of DUI, the officer typically checks for signs of impairment and may ask the driver to submit to a breathalyzer test to determine his or her breath-alcohol (BrAC) or blood alcohol concentration (BAC). But not everyone willingly provides a breath sample and police officers cannot force DUI suspects to blow into a tube. More than 20 percent of drunk driving suspects in the U.S. refuse to take a breathalyzer or other BAC test when an officer suspects drunk driving, according to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA). It varies greatly from state to state, from 2.4 percent in Delaware to 81 percent in New Hampshire (based on 2005 data cited by NHTSA). The act of refusal, though, comes with its own penalties. Under "implied consent" laws in all states, when they apply for a driver's license, motorists give consent to test or tests to determine impairment. Should a driver refuse to submit to testing when an officer has reasonable suspicion that the driver is under the influence, the driver risks automatic license suspension along with possible further penalties. Consequences for breathalyzer refusal vary by state, which may explain the wide variance in statewide refusal rates, but most states impose an automatic driver's license suspension upon refusal of a BAC/BrAC test. Suspensions usually increase for a refusing motorist with past DUI convictions, sometimes including jail time. DEFINITION OF IMPLIED CONSENT A. -

Engthening the List of Hu- Does Not Survive, We Do Not Exist

VULNERABLE BODIES Caring as a Political Horizon 177 José Laguna VULNERABLE BODIES CARING AS A POLITICAL HORIZON José Laguna Introduction ............................................................................................ 3 1. Adam and Eve (Hidden Bodies) ......................................................... 9 2. The Vitruvian Man (Dispensable Body) ........................................... 15 3. Benjamina (Vulnerable Body) .......................................................... 19 Notes ......................................................................................................... 31 “We are all born poor and naked; we are all subject to disease and misery of every type, and finally we are condemned to death. The sight of these common miseries can, therefore, carry our hearts to humanity if we live in a society that encourages us to imagine the life of others.” Martha Nussbaum, Los límites del patriotismo. Identidad, pertenencia y “ciudadanía mundial”. José Laguna is a theologian, a musician, and a member of the theological area of Cristianisme i Justícia. His earlier contributions to this collection are: And if God were not perfect? (Book- let no. 99); Taking stock of reality, taking responsibility for reality, and taking charge of reality (Booklet no. 143); Evangelical Dystopias (Booklet no. 148); Stepping on the Moon: Eschatology and Politics (Booklet no. 162); Seeking Sanctuary: The Political Construction of Habitable Places (Booklet no. 174). Publisher: CRISTIANISME I JUSTÍCIA - Roger de Llúria 13 - 08010 -

GGD-00-41 Racial Profiling: Limited Data Available on Motorist Stops

United States General Accounting Office Report to the Honorable GAO James E. Clyburn, Chairman Congressional Black Caucus March 2000 RACIAL PROFILING Limited Data Available on Motorist Stops GAO/GGD-00-41 United States General Accounting Office General Government Division Washington, D.C. 20548 B-283949 March 13, 2000 The Honorable James E. Clyburn Chairman, Congressional Black Caucus Dear Mr. Chairman: Racial profiling of motorists by law enforcement—that is, using race as a key factor in deciding whether to make a traffic stop—is an issue that has received increased attention in recent years. Numerous allegations of racial profiling of motorists have been made and several lawsuits have been won. As agreed with your office, this report provides information on (1) the findings and methodologies of analyses that have been conducted on racial profiling of motorists; and (2) federal, state, and local data currently available, or expected to be available soon, on motorist stops. We found no comprehensive, nationwide source of information that could Results in Brief be used to determine whether race has been a key factor in motorist stops. The available research is currently limited to five quantitative analyses that contain methodological limitations; they have not provided conclusive empirical data from a social science standpoint to determine the extent to which racial profiling may occur. However, the cumulative results of the analyses indicate that in relation to the populations to which they were compared, African American motorists in particular, and minority motorists in general, were proportionately more likely than whites to be stopped on the roadways studied. Data on the relative proportion of minorities stopped on a roadway, however, is only part of the information needed from a social science perspective to assess the degree to which racial profiling may occur. -

Fayetteville GA Rotary - Song of the W…

7/11/2010 Fayetteville GA Rotary - Song of the W… Song of the Week Welcome Welcome 2009- 2010 print this page Welcome 2009 and earlier PLANNING GUIDE Meeting Information Meeting Schedule SEND YOUR SONG REQUEST TO PAUL ODDO AT [email protected]. We've got 50 years of the Meeting Makeups music Rotary loves best! President's Message Officers & Directors How Singing came to Rotary, and Club Members Off-Color Jokes did not! Four Avenues of Service Paul Harris Fellow Almost everyone who is a member of a Rotary club for more than a year knows that Rotary member Newsletter No. 5, Chicago printer Harry Ruggles, brought singing to Rotary meetings. What almost no one knows Photo Album is why, and most don’t know how important it was to the life of Rotary. Calendar Harry Ruggles was a very moral man. He detested off-color language, About Rotary malicious innuendo and classless humor. He argued in club meetings for Becoming A Member clean language. Little more than a year after Rotary had been formed, at an Useful Links evening meeting in 1906, the guest speaker began a story. Having heard it before, Harry also had heard the off-color ending, and felt it was Contact Us inappropriate for the club, so hejumped up in the middle of the joke and Site Map yelled, “Come on boys, let's sing!” He then led the club in the singing of “Let Guest Speaker Me Call You Sweetheart.” District 6900 Conference This was not only the first time that members had ever sung in Rotary, but apparently, also the first Sporting Clay Event time that a group of businessmen ever sang at a business meeting, anywhere.