Tenant Rights and Compensation Issues

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Landlord and Tenant Act 1954

c i e AT 8 of 1954 LANDLORD AND TENANT ACT 1954 Landlord and Tenant Act 1954 Index c i e LANDLORD AND TENANT ACT 1954 Index Section Page 1 Short title and construction ........................................................................................... 5 2 Saving clause ................................................................................................................... 5 3 Interpretation ................................................................................................................... 5 Nature of Tenancies and the Law applicable thereto 6 4 Kinds of tenancies ........................................................................................................... 6 5 Tenancies and the law applicable thereto ................................................................... 7 Capacity for Letting Property 7 6 General contract law to govern capacity to enter into tenancies ............................. 7 Provisions relating to Contracts of Tenancy 8 7 Agreements of tenancy for more than one year to be in writing ............................. 8 8 Annual tenancies ............................................................................................................ 8 9 Void periodic tenancies.................................................................................................. 8 10 Tenancy deemed annual tenancy unless contrary be proved .................................. 9 11 Authority to doweress, tenant by curtesy, etc, to grant leases ................................. 9 12 Recovery -

Georgia Landlord-Tenant Handbook |1

GEORGIA LANDLORD TENANT HANDBOOK A Landlord-Tenant Guide to the State’s Rental Laws Revised February 2021 Georgia Landlord-Tenant Handbook |1 Introduction This Handbook provides an overview and answers common questions about Georgia residential landlord-tenant law. The information in this Handbook does not apply to commercial or business leases. The best solution for each case depends on the facts. Because facts in each case are different, this Handbook covers general terms and answers, and those answers may not apply to your specific problem. While this publication may be helpful to both landlords and tenants, it is not a substitute for professional legal advice. This Handbook has information on Georgia landlord-tenant law as of the last revision date and may not be up to date on the law. Before relying on this Handbook, you should independently research and analyze the relevant law based on your specific problem, location, and facts. In Georgia, there is not a government agency that can intervene in a landlord-tenant dispute or force the landlord or tenant to behave a particular way. Landlords or tenants who cannot resolve a dispute need to use the courts, either directly or through a lawyer, to enforce their legal rights. The Handbook is available on the internet or in print (by request) from the Georgia Department of Community Affairs (www.dca.ga.gov). Table of Contents Relevant Law 3 Entering into a Lease and Other Tenancy Issues 5 1. Submitting a Rental Application 5 2. Reviewing and Signing a Lease 5 3. Problems During a Lease: 10 4. -

An Introduction to Social Housing, Second Edition

An Introduction to Social Housing Prelims.qxd 1/21/05 11:30 AM Page ii To my wife, Marlena, with all my love. Prelims.qxd 1/21/05 11:30 AM Page iii An Introduction to Social Housing Second edition PAUL REEVES MA(CANTAB) MCIH PGCE(HE) MCMI AMSTERDAM BOSTON HEIDELBERG LONDON NEW YORK OXFORD PARIS SAN DIEGO SAN FRANCISCO SINGAPORE SYDNEY TOKYO Prelims.qxd 1/21/05 11:30 AM Page iv Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann Linacre House, Jordan Hill, Oxford OX2 8DP 30 Corporate Drive, Burlington, MA 01803 First published in 1996 by Arnold Second edition 2005 Copyright © 1996, P. Reeves; © 2005, Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any material form (including photocopying or storing in any medium by electronic means and whether or not transiently or incidentally to some other use of this publication) without the written permission of the copyright holder except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 or under the terms of a licence issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency Ltd, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4LP, England. Applications for the copyright holder’s written permission to reproduce any part of this publication should be addressed to the publisher Permissions may be sought directly from Elsevier’s Science and Technology Rights Department in Oxford, UK: phone: (44) (0) 1865 843830; fax: (44) (0) 1865 853333; e-mail: [email protected]. You may also complete your request on-line via the Elsevier Science homepage (www.elsevier.com), by selecting ‘Customer Support’ and then ‘Obtaining Permissions’ ISBN 0 7506 63936 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library For information on all Butterworth-Heinemann publications visit our website at http://bookselsevier.com Typeset by Charon Tec Pvt. -

Chapter 9 LANDLORD and TENANT LAW Table of Sections Soc

Selected Readings 12 a. LANDLOIIDANDTI!NAN1' A. N.\TURE OrJ.ll!A.WtOIJI A It!Isc:hoId ;. .. _ ill lII:l4 TIle _llu *~ jlOQ! .. "Y iooltesI in die ~ i'R' lllises. aIIII dill IondIanI b.,. 4 fUture ~ (~. Ccttain tiaJIIIi lIA4li11lti1itios flow (Mill 1M ~y rtla!icmblp btt_ b:ndklnl1III<I _ The Ihn:o IIII\iO< 1)'pC> of l--""ld _eo are-w'}tw,....~"" •• da.oad"'......... &lIriU.n-: .. ar-dl~ .... 1e4 __1tI~. a. Fbd ...... "'n- A !ella:)' for )'UI'$ ;. "'"' tIM .. '" ....1IiIM roc. fW:o.I poriW of lin... n ...y bo ri.x _ ....than .,...,(•. , .• Uld"l"' .... 10 yeotS); »1IIIIY be ""nahle lsimilarto • fee .....1<0 ....~, nt 041 ~ ~ 'I'M leI'mlIoaIion date of a len&ro:y 1« )'em is IISU8lJy cctltill. Ali • """II. lIIc ICNIIICy npim 1lI die end of die ~ period ....., tiIiB,.".,,m., IIIIIfcI ,. 1M ..... 1:Nai If dill dale 0{ terJnI.. IlIIiooI is ID1CCIIIia (e.R .• L Joascs IIIc premises to T "uaIillllc cad 0{ /be ...,")._ - hold _ iidllll'lidico hovelll<mJlltd w __ """'" pGriod of <kII:IoOOD. liNt..... c'lU1t$ a I~ fer ycm. II. CraoIiom 'IirraQcia, for yea'llille DIlrIJlOIy ~ by om-.Ieues. Tn mea 5l.1li.., Illa S!aIJJIv 0( l-ilIurk ~ duK ! lea!IC <!realms a Il:ruJIlCy r.... mun! than _ 'jeJIE be ill wrilinfl. fa REAL PROPERTY 35. addition. most states have starutes that restrict the number of years {or wh:cb a lease~ holdestale may be creared (e.g .. 51 years for farm property and 99 years for urban property). When the lease term exceeds the statutory maximum. -

THE LANDLORD and TENANT ACTS, 1948 to 1961

629 THE LANDLORD AND TENANT ACTS, 1948 to 1961 Landlord and Tenant Act of 1948, 12 Geo. 6 No. 31 Amended by Landlord and Tenant Act Amendment Act of 1948, 12 Geo. 6 No. 46 Landlord and Tenant Act Amendment Act of 1949, 13 Geo. 6 No. 31 Landlord and Tenant Acts Amendment Act of 1950, 14 Geo. 6 No.9 Landlord and Tenant Acts Amendment Act of 1954, 3 Eliz. 2 No. 42 Landlord and Tenant Acts Amendment Act of 1957, 6 Eliz. 2 No. 35 Landlord and Tenant Acts Amendment Act of 1961, 10 Eliz. 2 No. 29 An Act Relating to the Determination of Fair Rents of Dwelling-houses and the Recovery of Possession of Premises, and for other purposes [Assented to 1 September 1948J PART I-PRELIMINARY 1. Short title and construction. This Act may be cited as "The Landlord and Tenant Act of 1948." Collective title conferred by Act of 1961. 10 Eliz. 2 No. 29. s. 1. 2. Construction of Act. This Act and every Order in Council and regulation made under this Act shall be read and construed so as not to exceed the legislative power of the State to the intent that where any enactment hereof or provision of any such Order in Council or regulation would but for this section have been construed as being in excess of that power it shall nevertheless be a valid enactment or provision to the extent to which it is not in excess of that power. 3. Parts of Act. This Act is divided into Parts, as follows: PART I-PRELIMINARY; PART II-RENT CONTROL- Division I-The Court; Division II-Fair Rents; Division III-General; PART III-RECOVERY OF POSSESSION; PART IV-MISCELLANEOUS. -

Global Practice Guides

GLOBAL PRACTICE GUIDES Definitive global law guides offering comparative analysis from top-ranked lawyers Real Estate Ireland Diarmuid Mawe, Craig Kenny and Katelin Toomey Maples Group practiceguides.chambers.com 2021 IRELAND Law and Practice Contributed by: Diarmuid Mawe, Craig Kenny and Katelin Toomey Maples Group see p.21 CONTENTS 1. General p.4 4. Planning and Zoning p.11 1.1 Main Sources of Law p.4 4.1 Legislative and Governmental Controls 1.2 Main Market Trends and Deals p.4 Applicable to Strategic Planning and Zoning p.11 1.3 Impact of Disruptive Technologies p.4 4.2 Legislative and Governmental Controls Applicable to Design, Appearance and Method 1.4 Proposals for Reform p.4 of Construction p.11 2. Sale and Purchase p.4 4.3 Regulatory Authorities p.11 2.1 Categories of Property Rights p.4 4.4 Obtaining Entitlements to Develop a New Project p.11 2.2 Laws Applicable to Transfer of Title p.4 4.5 Right of Appeal Against an Authority’s Decision p.12 2.3 Effecting Lawful and Proper Transfer of Title p.4 4.6 Agreements with Local or Governmental Authorities p.12 2.4 Real Estate Due Diligence p.5 4.7 Enforcement of Restrictions on Development 2.5 Typical Representations and Warranties p.5 and Designated Use p.12 2.6 Important Areas of Law for Investors p.6 2.7 Soil Pollution or Environmental Contamination p.6 5. Investment Vehicles p.12 2.8 Permitted Uses of Real Estate under Zoning or 5.1 Types of Entities Available to Investors to Hold Planning Law p.6 Real Estate Assets p.12 2.9 Condemnation, Expropriation or Compulsory 5.2 Main Features of the Constitution of Each Type Purchase p.6 of Entity p.13 2.10 Taxes Applicable to a Transaction p.7 5.3 Minimum Capital Requirement p.13 2.11 Legal Restrictions on Foreign Investors p.7 5.4 Applicable Governance Requirements p.14 5.5 Annual Entity Maintenance and Accounting 3. -

Georgia Supreme Ct – Leased Local Gov. Owned Property Can't Be Posted Unless Certain

In the Supreme Court of Georgia Decided: October 7, 2019 S18G1149. GEORGIACARRY.ORG., INC. et al. v. ATLANTA BOTANICAL GARDEN, INC. BETHEL, Justice. The Atlanta Botanical Garden, Inc. (the “Garden”) leases land from the City of Atlanta where the Garden maintains and nurtures an extensive garden complex. The Garden wishes to enforce a policy precluding the possession of firearms by visitors to, and guests of, the Garden, like Phillip Evans. Evans holds a valid weapons carry license under Georgia law and asserts that he is authorized to carry a firearm at the garden under the authority of OCGA § 16-11-127 (c), which provides that license holders “shall be authorized to carry a weapon . in every location in this state not [excluded by] this Code section.” The Garden counters that it may enforce its policy based on an exception to the general rule found in the same statutory paragraph. Specifically, the Garden claims that it may exclude Evans because it is, in the words of the statute, “in legal control of private property through a lease” and is thus entitled “to exclude or eject a person who is in possession of a weapon . on their private property.” Id. As a preliminary matter, it is worth noting that the resolution of this appeal does not turn on an interpretation or understanding of the Second Amendment to the Constitution of the United States1 or of Article 1, Section 1, Paragraph VIII of the Georgia Constitution.2 Nor does this appeal require us to determine whether the statute runs afoul of other provisions of the United States Constitution or the Georgia Constitution regarding property rights. -

Gba Sample Property Lease

GBA SAMPLE PROPERTY LEASE STATE OF GEORGIA No. of Two COUNTY OF FULTON Executed Copies LEASE AGREEMENT – SPECIMEN BY AND BETWEEN THE GEORGIA BUILDING AUTHORITY AND {NAME OF TENANT} THIS LEASE AGREEMENT (hereinafter referred to as “Lease”), made this day of ___________, 2012, between GEORGIA BUILDING AUTHORITY (hereinafter referred to as “Landlord”), a public corporation created by an Act of the General Assembly of Georgia (Ga. Laws 1951, p. 699, as amended), whose agent for purposes of this Lease is Steven L. Stancil., Executive Director and with the business address for purposes hereof at 1 Martin Luther King, Jr. Drive, S.W., Atlanta, Georgia 30334 and {NAME OF TENANT}, (hereinafter called “Tenant”) and business address for purposes of this Lease is {insert business Address}, and whose mailing address is {insert mailing address}; WITNESSETH 1. PREMISES. Landlord hereby demises and leases to Tenant, and Tenant hereby accepts and leases from Landlord, subject to the terms and conditions hereof, the premises being and situated at {insert address of property to be leased} comprising the portion of the Balcony Level floor totaling {insert square footage} square feet and being more particularly identified on a floor plan of said building designated “Exhibit A”, attached hereto and made a part hereof, and with the foregoing premises hereinafter known and referred to as the “Premises”, for the express purpose of {insert purpose of business} and for no other purpose. 2. TERM. The initial term of this Lease, hereinafter called the “TERM”, shall commence on {insert base term of lease} at the Base Rent as hereinbelow defined, and will continue pursuant to Paragraph 4 within unless, however, sooner terminated as herein defined. -

Real Estate Market Meltdown, Foreclosures and Tenants' Rights

REAL ESTATE MARKET MELTDOWN, FORECLOSURES AND TENANTS’ RIGHTS A LEATRA P. WILLIAMS* INTRODUCTION The nearly unparalleled levels of foreclosures resulting from the current real estate market meltdown reveal a significant gap in laws that address residential tenant rights. There exists a misconception by the general public that foreclosures only affect single family, owner-occupied homes, but foreclosures have also occurred on multiple family units and non-owner occupied homes in alarming numbers.1 Until recently, tenants who lived in foreclosed properties typically had no legal recourse (or viable legal remedies) when confronted with eviction or ejectment proceedings precipitated by foreclosure actions against their landlords and/or property owners. These proceedings occurred notwithstanding compliance with lease agreements and other public policy obligations, thus potentially burdening already strained social programs for the homeless and impoverished. Therefore, foreclosures have been gut wrenchingly devastating for tenants and have especially hit hard tenants in vulnerable low- income and in minority communities. In May 2009, the federal government took an unprecedented step into the landlord-tenant arena, which is traditionally and exclusively governed by state legislatures, when President Obama signed into law the Protecting Tenants at Foreclosure Act of 2009 (the “Act” or PTFA).2 This step by the federal government manifestly indicates that the ills tenants face when their leased premises are foreclosed upon are indeed grave and that tenants do warrant protection.3 The Act applies to all foreclosures of federally-related mortgages * Assistant Professor, Charleston School of Law; B.A., Purdue University; J.D., University of Oklahoma; LL.M., University of California, Berkeley. -

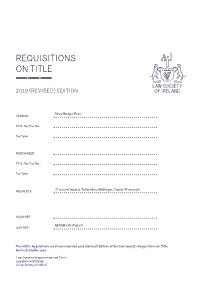

Requisitions on Title 1057484.PDF

REQUISITIONS ON TITLE 2019 (REVISED) EDITION VENDOR: P.P.S. No./Tax No.: Tax Type: PURCHASER: P.P.S. No./Tax No. : Tax Type: PROPERTY: YOUR REF: OUR REF: The within Requisitions are the unamended 2019 (Revised) Edition of the Law Society’s Requisitions on Title. Revised October 2020 Law Society Requisitions on Title 2019 (Revised) Edition ©Law Society of Ireland INDEX TO REQUISITIONS ON TITLE Req. No. Title Page No. 1. Premises 2 2 Water Services/Local Authority Services 2 3. Easements and Rights 3 4. Obligations/Privileges 3 5. Forestry 4 6. Fishing 4 7. Sporting 4 8. Possession 5 9. Commercial Tenancies 5 10. Tenancies – Residential Only 6 11. Outgoings 8 12. Notices 9 13. Searches 11 14. Incumbrances/Proceedings 11 15. Voluntary Dispositions/Bankruptcy 13 16. Taxation 14 17. Non Resident Vendor 15 18. Body Corporate Vendor on Title 15 19. Land Acts 1965 to 2005 16 20. Unregistered Property 17 21. Identity 17 22. Registered Property 17 23.-25. Family Law 18 26. Planning 19 27. Building Control 22 28. Safety Health and Welfare at Work 24 29. Newly Erected Property 24 30. Fire Services Acts 1981 and 2003 25 31. Environmental 26 32. Food and Feed Hygiene 27 33. Leasehold/Fee Farm Grant Property 28 34. Acquisition of Fee Simple 29 35. Local Government (Multi Storey Buildings) Act 1988 31 36. MUDs Property 32 37. Non-MUDs Property 35 38. Tax Based Incentives/Designated Areas 38 39. National Asset Management Agency Act 2009 39 40. Licensing 41 41. Restaurant/Hotel 43 42. Special Restaurant Licence 44 43. -

Louisiana Civil Law Property As Relates to Real Estate, Under Louisiana Law, the Term

Louisiana Civil Law Property As relates to Real Estate, under Louisiana law, the term “Property” generally refers to any portion of immovable property, including servitudes, leases, rights-of-way, and other rights in or to immovable property. In Louisiana, property means things. The term is also used in reference to the relationship that exists between people and property. Property, or things, can fall into several classifications that are not mutually exclusive. Property is further categorized by Classification, Immovables vs. Movables, and its Legal Description. Property “Property” can also refer to a person’s community or separate property. Community Property is all property which a couple acquires after the establishment of their community regime (marriage). Unless a married couple have entered into pre/post marriage contract, which specifies that certain property acquired during the community regime will be separate, all property that a couple acquires during the community will be deemed community property. Additionally, any income derived from separate property, during the community, will be deemed community, unless specifically reserved as one’s separate property. Each spouse is deemed to own ½ of the property designated as community property. Separate Property is all of the property which a person owns outside of the community, or which he acquires during the community subject to marriage agreement designating the property as separate. A person’s separate property can also include inherited property, received during the community, when the property is left to the person in his individual capacity. Classification In Louisiana, property is classified either as an immovable or a movable. Immovables Under Article 462, of the Louisiana Civil Code, an “Immovable” is defined as a tract of land together with its component parts. -

Legislation and Regulations

STATUTES HISTORICALY SIGNIFICANT ENGLISH STATUTES SIGNIFICANT U.S. FEDERAL LEGISLATION AND REGULATIONS STATUTORY REFERENCES IN THE ENCYCLOPEDIA ENGLISH STATUTES A B C D E F G H I-K L M N O P R S T U-Z US STATUTES Public Acts and Codes Uniform Commercial Code Annotated (USCA) State Codes AUSTRALIAN STATUTES CANADIAN STATUTES & CODES NEW ZEALAND STATUTES FRENCH CODES & LEGISLATION French Civil Code Other French Codes French Laws & Decrees OTHER CODES 1 back to the top STATUTES HISTORICALLY SIGNIFICANT ENGLISH STATUTES De Donis Conditionalibus 1285 ................................................................................................................................. 5 Statute of Quia Emptores 1290 ................................................................................................................................ 5 Statute of Uses 1536.................................................................................................................................................. 5 Statute of Frauds 1676 ............................................................................................................................................. 6 SIGNIFICANT SIGNIFICANT ENGLISH STATUTES Housing Acts ................................................................................................................................................................. 8 Land Compensation Acts ........................................................................................................................................