Tyneside Flats: a Paradigm Tenure for Interconnected Dwellings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

R Ed Arrow S Buses Betw Een Easington Lane, Houghton-Le

Get in touch be simpler! couldn’t with us Travelling simplygo.com the Go North East app. mobile with your to straight times and tickets Live Go North app East 0191 420 5050 0191 Call: @gonortheast Twitter: facebook.com/simplyGNE Facebook: simplygo.com/contact-us chat: web Live /redarrows 5 mins /gneapp simplygo.com Buses run up to Buses run up to 10 minutes every ramp access find You’ll bus and travel on every on board. advice safety simplygo.com smartcard. deals on exclusive with everyone, easier for cheaper and travel Makes smartcard the key /thekey the key the key X1 Go North East Bus times from 28 February 2016 28 February Bus times from Serving: Easington Lane Hetton-le-Hole Houghton-le-Spring Newbottle Row Shiney Washington Galleries Springwell Wrekenton Queen Elizabeth Hospital Gateshead Newcastle Red Arrows Arrows Red Easington Lane, Buses between Washington Houghton-le-Spring, and Newcastle Red Arrows timetable X1 — Newcastle » Gateshead » Wrekenton » Springwell » Washington Galleries » Shiney Row » Houghton-le-Spring » Hetton-le-Hole » Easington Lane Mondays to Fridays (except Public Holidays) Every 10 minutes until Service number X1 X1 X1 X1 X1 X1 X1 X1 X1 X1 X1 X1 X1 X1 X1 X1 X1 X1 X1 X1 X1 X1 X1 X1 X1 X1 X1 X1 X1 X1A X1 X1 X1 X1A X1 X1 X1 X1 X1 X1 X1 CODES C C Newcastle Eldon Square - - - 0630 0700 - 0720 0740 0800 0818 0835 0850 0905 1415 1425 1435 1445 1455 1505 1517 1527 1537 1550 1600 1610 1620 1630 1640 1650 1658 1705 1713 1720 1727 1735 1745 1755 1805 1815 1825 1840 Gateshead Interchange - - - 0639 0709 - 0730 0750 -

Ashfield Road | Gosforth | Newcastle Upon Tyne | NE3 4XL £650 Per Calendar Month 2 1 1

Ashfield Road | Gosforth | Newcastle Upon Tyne | NE3 4XL £650 Per calendar month 2 1 1 • Fully Refurbished Throughout • Available NOW • Unfurnished Basis • Council Tax Band *A* • Ground Floor Flat • Two Bedrooms • Excellent Location • NO DAMAGE DEPOSIT • Just off Gosforth High Street • Easy Access to City Centre **NO DAMAGE DEPOSIT REQUIRED** Two Bedroom ground floor Tyneside flat with modern fixtures and fittings throughout and very much ready to move into. Located just off Salters Road in Gosforth, the flat benefits from many local amenities including shops, schools and parks with Gosforth High street only a short walk away. Internally the property should appeal to a range of applicants as a result of the recent refurbishment throughout. The accommodation briefly comprises:- Entrance hall, lounge/diner, kitchen, two bedrooms and a bathroom/w.c. Additional benefits to the property include double glazing and gas central heating. Offered with immediate availability this stunning flat is definitely worth a view. The difference between house and home You may download, store and use the material for your own personal use and research. You may not republish, retransmit, redistribute or otherwise make the material available to any party or make the same available on any website, online service or bulletin board of your own or of any other party or make the same available in hard copy or in any other media without the website owner's express prior written consent. The website owner's copyright must remain on all reproductions of material taken from this website. www.janforsterestates.com. -

Newcastle, NE4 & NE10

Newcastle, NE4 & NE10 A development / investment opportunity comprising 17 residential units located in the Benwell and Felling suburbs of Newcastle upon Tyne. 0113 292 5500 gva.co.uk/13822 Executive Summary Description · Residential development / investment opportunity. The portfolio comprises 16 self-contained flats (Tyneside flats) within brick built terrace properties. · Comprises 17 units and 1 freehold reversionary interest. Typically a Tyneside flat is arranged to allow for the division of a property title into a number of units, usually two. Each unit is held on a leasehold title subject to the reversionary interest in the opposing · 2 occupied properties within the portfolio producing a rental income of £7,680 per annum. unit. The remaining property in the portfolio comprises a standard terrace house. · Excellent opportunity for asset management and rental growth. Within the portfolio 15 units are currently vacant. These units require refurbishment and modernisation. · Estimate that the portfolio has the potential to generate a rental income of £77,736 per annum.* This presents the unique opportunity to actively manage the properties and increase the occupancy · Grants and interest free loans available against the vacant properties across the portfolio. rate across the portfolio. · Offers invited. The Disposal Process * Subject to undertaking works to bring the properties into a reasonable condition. We are instructed as the Receiver’s sole agent to market the portfolio by way of private treaty. Our clients will consider both offers for the entire portfolio and also proposals for individual properties or Location multiple lots. The portfolio offers properties located in Benwell and Felling, two residential suburbs on the periphery of Newcastle upon Tyne. -

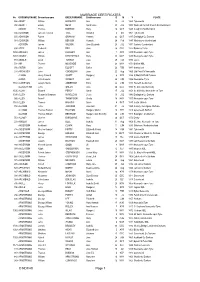

MARRIAGE CERTIFICATES © NDFHS Page 1

MARRIAGE CERTIFICATES No GROOMSURNAME Groomforename BRIDESURNAME Brideforename D M Y PLACE 588 ABBOT William HADAWAY Ann 25 Jul 1869 Tynemouth 935 ABBOTT Edwin NESS Sarah Jane 20 JUL 1882 Wallsend Parrish Church Northumbrland ADAMS Thomas BORTON Mary 16 OCT 1849 Coughton Northampton 556 ADAMSON James Frederick TATE Annabell 6 Oct 1861 Tynemouth 655 ADAMSON Robert GRAHAM Hannah 23 OCT 1847 Darlington Co Durham 581 ADAMSON William BENSON Hannah 24 Feb 1847 Whitehaven Cumberland ADDISON James WILSON Jane Elizabeth 23 JUL 1871 Carlisle, Cumberland 694 ADDY Frederick BELL Jane 26 DEC 1922 Barnsley Yorks 1456 AFFLECK James LUCKLEY Ann 1 APR 1839 Newcastle upon Tyne 1457 AGNEW William KIRKPATRICK Mary 30 MAY 1887 Newcastle upon Tyne 751 AINGER David TURNER Eliza 28 FEB 1870 Essex 704 AIR Thomas MCKENZIE Ann 24 MAY 1871 Belford NBL 936 AISTON John ELLIOTT Esther 26 FEB 1881 Sunderland 244 AITCHISON John COCKBURN Jane 22 Aug 1865 Utd Pres Ch Newcastle ALBION Henry Edward SCOTT Margaret 6 APR 1884 St Mark Millfield Durham ALDER John Cowens WRIGHT Ann 24 JUN 1856 Newcastle /Tyne 1160 ALDERSON Joseph Henry ANDERSON Eliza 22 JUN 1897 Heworth Co Durham ALLABURTON John GREEN Jane 24 DEC 1842 St. Giles ,Durham City 1505 ALLAN Edward PERCY Sarah 17 JUL 1854 St. Nicholas, Newcastle on Tyne 1390 ALLEN Alexander Bowman WANDLESS Jessie 10 JUL 1943 Darlington Co Durham 992 ALLEN Peter F THOMPSON Sheila 18 MAY 1957 Newcastle upon Tyne 1161 ALLEN Thomas HIGGINS Annie 4 OCT 1887 South Shields 158 ALLISON John JACKSON Jane Ann 31 Jul 1859 Colliery, Catchgate, -

Full Property Address Primary Liable

Full Property Address Primary Liable party name 2019 Opening Balance Current Relief Current RV Write on/off net effect 119, Westborough, Scarborough, North Yorkshire, YO11 1LP The Edinburgh Woollen Mill Ltd 35249.5 71500 4 Dnc Scaffolding, 62, Gladstone Lane, Scarborough, North Yorkshire, YO12 7BS Dnc Scaffolding Ltd 2352 4900 Ebony House, Queen Margarets Road, Scarborough, North Yorkshire, YO11 2YH Mj Builders Scarborough Ltd 6240 Small Business Relief England 13000 Walker & Hutton Store, Main Street, Irton, Scarborough, North Yorkshire, YO12 4RH Walker & Hutton Scarborough Ltd 780 Small Business Relief England 1625 Halfords Ltd, Seamer Road, Scarborough, North Yorkshire, YO12 4DH Halfords Ltd 49300 100000 1st 2nd & 3rd Floors, 39 - 40, Queen Street, Scarborough, North Yorkshire, YO11 1HQ Yorkshire Coast Workshops Ltd 10560 DISCRETIONARY RELIEF NON PROFIT MAKING 22000 Grosmont Co-Op, Front Street, Grosmont, Whitby, North Yorkshire, YO22 5QE Grosmont Coop Society Ltd 2119.9 DISCRETIONARY RURAL RATE RELIEF 4300 Dw Engineering, Cholmley Way, Whitby, North Yorkshire, YO22 4NJ At Cowen & Son Ltd 9600 20000 17, Pier Road, Whitby, North Yorkshire, YO21 3PU John Bull Confectioners Ltd 9360 19500 62 - 63, Westborough, Scarborough, North Yorkshire, YO11 1TS Winn & Co (Yorkshire) Ltd 12000 25000 Des Winks Cars Ltd, Hopper Hill Road, Scarborough, North Yorkshire, YO11 3YF Des Winks [Cars] Ltd 85289 173000 1, Aberdeen Walk, Scarborough, North Yorkshire, YO11 1BA Thomas Of York Ltd 23400 48750 Waste Transfer Station, Seamer, Scarborough, North Yorkshire, -

Tyne and Wear Historic Landscape Characterisation Final Report

Tyne and Wear Historic Landscape Characterisation Final Report English Heritage Project Number 4663 Main Sarah Collins McCord Centre Report 2014.1 Project Name and Tyne and Wear Historic Landscape Characterisation (HLC) EH Reference Number: English Heritage Project Number 4663 Authors and Contact Details: Sarah Collins, [email protected] Dr Oscar Aldred, [email protected] Professor Sam Turner, [email protected] Origination Date: 10th April 2014 Revisers: Dr Oscar Aldred Date of Last Revision: 15th September 2014 Version: 2 Summary of Changes: McCord Centre Report 2014.1 Front piece: (Top) Captain’s Wharf South Tyneside (Sarah Collins); (Middle) Visualisation of Tyne and Wear HLC using ArcGIS (Sarah Collins) EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Sam Turner, Ian Ayris and Sarah Collins This report provides an overview of the Tyne & Wear Historic Landscape Characterisation (HLC) Project. The project was undertaken between 2012 and 2014 by Newcastle University in partnership with Newcastle City Council and funded by English Heritage as part of a national programme of research. Part One of the report sets the Tyne & Wear HLC (T&WHLC) in its national context as one of the last urban based research projects in the English Heritage programme. It provides some background to the T&W region as well as the research aims and objectives since the projects inception in 2010. The report also discusses the characterisation methodology, data structure and the sources used. Part Two provides an analysis of the main findings of the project by summarising the urban and peri-urban, rural, and industrial landscapes that make up the T&W project area. -

Northumberland and Durham Family History Society Unwanted

Northumberland and Durham Family History Society baptism birth marriage No Gsurname Gforename Bsurname Bforename dayMonth year place death No Bsurname Bforename Gsurname Gforename dayMonth year place all No surname forename dayMonth year place Marriage 933ABBOT Mary ROBINSON James 18Oct1851 Windermere Westmorland Marriage 588ABBOT William HADAWAY Ann 25 Jul1869 Tynemouth Marriage 935ABBOTT Edwin NESS Sarah Jane 20 Jul1882 Wallsend Parrish Church Northumbrland Marriage1561ABBS Maria FORDER James 21May1861 Brooke, Norfolk Marriage 1442 ABELL Thirza GUTTERIDGE Amos 3 Aug 1874 Eston Yorks Death 229 ADAM Ellen 9 Feb 1967 Newcastle upon Tyne Death 406 ADAMS Matilda 11 Oct 1931 Lanchester Co Durham Marriage 2326ADAMS Sarah Elizabeth SOMERSET Ernest Edward 26 Dec 1901 Heaton, Newcastle upon Tyne Marriage1768ADAMS Thomas BORTON Mary 16Oct1849 Coughton Northampton Death 1556 ADAMS Thomas 15 Jan 1908 Brackley, Norhants,Oxford Bucks Birth 3605 ADAMS Sarah Elizabeth 18 May 1876 Stockton Co Durham Marriage 568 ADAMSON Annabell HADAWAY Thomas William 30 Sep 1885 Tynemouth Death 1999 ADAMSON Bryan 13 Aug 1972 Newcastle upon Tyne Birth 835 ADAMSON Constance 18 Oct 1850 Tynemouth Birth 3289ADAMSON Emma Jane 19Jun 1867Hamsterley Co Durham Marriage 556 ADAMSON James Frederick TATE Annabell 6 Oct 1861 Tynemouth Marriage1292ADAMSON Jane HARTBURN John 2Sep1839 Stockton & Sedgefield Co Durham Birth 3654 ADAMSON Julie Kristina 16 Dec 1971 Tynemouth, Northumberland Marriage 2357ADAMSON June PORTER William Sidney 1May 1980 North Tyneside East Death 747 ADAMSON -

Sit Back and Enjoy the Ride

MAIN BUS ROUTES PLACES OF INTEREST MAIN BUS ROUTES Abbots of Leeming 80 and 89 Ampleforth Abbey Abbotts of Leeming Arriva X4 Sit back and enjoy the ride Byland Abbey www.northyorkstravel.info/metable/8089apr1.pdf Arriva X93 Daily services 80 and 89 (except Sundays and Bank Holidays) - linking Castle Howard Northallerton to Stokesley via a number of villages on the Naonal Park's ENJOY THE NORTH YORK MOORS, YORKSHIRE COAST AND HOWARDIAN HILLS BY PUBLIC TRANSPORT CastleLine western side including Osmotherley, Ingleby Cross, Swainby, Carlton in Coaster 12 & 13 Dalby Forest Visitor Centre Cleveland and Great Broughton. Coastliner Eden Camp Arriva Coatham Connect 18 www.arrivabus.co.uk Endeavour Experience Serving the northern part of the Naonal Park, regular services from East Yorkshire 128 Middlesbrough to Scarborough via Guisborough, Whitby and many villages, East Yorkshire 115 Flamingo Land including Robin Hood's Bay. Late evening and Sunday services too. The main Middlesbrough to Scarborough service (X93) also offers free Wi-Fi. X4 serves North Yorkshire County Council 190 Filey Bird Garden & Animal Park villages north of Whitby including Sandsend, Runswick Bay, Staithes and Reliance 31X Saltburn by the Sea through to Middlesbrough. Ryedale Community Transport Hovingham Hall Coastliner services 840, 843 (Transdev) York & Country 194 Kirkdale and St. Gregory’s Minster www.coastliner.co.uk Buses to and from Leeds, Tadcaster, Easingwold, York, Whitby, Scarborough, Kirkham Priory Filey, Bridlington via Malton, Pickering, Thornton-le-Dale and Goathland. Coatham Connect P&R Park & Ride Newburgh Priory www.northyorkstravel.info/metable/18sep20.pdf (Scarborough & Whitby seasonal) Daily service 18 (except weekends and Bank Holidays) between Stokesley, Visitor Centres Orchard Fields Roman site Great Ayton, Newton under Roseberry, Guisborough and Saltburn. -

Landlord and Tenant Act 1954

c i e AT 8 of 1954 LANDLORD AND TENANT ACT 1954 Landlord and Tenant Act 1954 Index c i e LANDLORD AND TENANT ACT 1954 Index Section Page 1 Short title and construction ........................................................................................... 5 2 Saving clause ................................................................................................................... 5 3 Interpretation ................................................................................................................... 5 Nature of Tenancies and the Law applicable thereto 6 4 Kinds of tenancies ........................................................................................................... 6 5 Tenancies and the law applicable thereto ................................................................... 7 Capacity for Letting Property 7 6 General contract law to govern capacity to enter into tenancies ............................. 7 Provisions relating to Contracts of Tenancy 8 7 Agreements of tenancy for more than one year to be in writing ............................. 8 8 Annual tenancies ............................................................................................................ 8 9 Void periodic tenancies.................................................................................................. 8 10 Tenancy deemed annual tenancy unless contrary be proved .................................. 9 11 Authority to doweress, tenant by curtesy, etc, to grant leases ................................. 9 12 Recovery -

Local Election Results 2007

Local Election Results 3rd May 2007 Tyne and Wear Andrew Teale Version 0.05 April 29, 2009 2 LOCAL ELECTION RESULTS 2007 Typeset by LATEX Compilation and design © Andrew Teale, 2007. The author grants permission to copy and distribute this work in any medium, provided this notice is preserved. This file (in several formats) is available for download from http://www.andrewteale.me.uk/ Please advise the author of any corrections which need to be made by email: [email protected] Chapter 4 Tyne and Wear 4.1 Gateshead Birtley Deckham Neil Weatherley Lab 1,213 Bernadette Oliphant Lab 1,150 Betty Gallon Lib 814 Daniel Carr LD 398 Andrea Gatiss C 203 Allan Davidson C 277 Kevin Scott BNP 265 Blaydon (2) Malcolm Brain Lab 1,338 Dunston and Teams Stephen Ronchetti Lab 1,047 Mark Gardner LD 764 Maureen Clelland Lab 940 Colin Ball LD 543 Michael Ruddy LD 357 Trevor Murray C 182 Andrew Swaddle BNP 252 Margaret Bell C 179 Bridges Bob Goldsworthy Lab 888 Dunston Hill and Whickham East Peter Andras LD 352 George Johnson BNP 213 Yvonne McNicol LD 1,603 Ada Callanan C 193 Gary Haley Lab 1,082 John Callanan C 171 Chopwell and Rowlands Gill Saira Munro BNP 165 Michael McNestry Lab 1,716 Raymond Callender LD 800 Maureen Moor C 269 Felling Kenneth Hutton BNP 171 Paul McNally Lab 1,149 David Lucas LD 316 Chowdene Keith McFarlane BNP 205 Steve Wraith C 189 Keith Wood Lab 1,523 Daniel Duggan C 578 Glenys Goodwill LD 425 Terrence Jopling BNP 231 High Fell Malcolm Graham Lab 1,100 Crawcrook and Greenside Ann McCarthy LD 250 Derek Anderson LD 1,598 Jim Batty UKIP 194 Helen Hughes Lab 1,084 June Murray C 157 Leonard Davidson C 151 Ronald Fairlamb BNP 151 48 4.1. -

Georgia Landlord-Tenant Handbook |1

GEORGIA LANDLORD TENANT HANDBOOK A Landlord-Tenant Guide to the State’s Rental Laws Revised February 2021 Georgia Landlord-Tenant Handbook |1 Introduction This Handbook provides an overview and answers common questions about Georgia residential landlord-tenant law. The information in this Handbook does not apply to commercial or business leases. The best solution for each case depends on the facts. Because facts in each case are different, this Handbook covers general terms and answers, and those answers may not apply to your specific problem. While this publication may be helpful to both landlords and tenants, it is not a substitute for professional legal advice. This Handbook has information on Georgia landlord-tenant law as of the last revision date and may not be up to date on the law. Before relying on this Handbook, you should independently research and analyze the relevant law based on your specific problem, location, and facts. In Georgia, there is not a government agency that can intervene in a landlord-tenant dispute or force the landlord or tenant to behave a particular way. Landlords or tenants who cannot resolve a dispute need to use the courts, either directly or through a lawyer, to enforce their legal rights. The Handbook is available on the internet or in print (by request) from the Georgia Department of Community Affairs (www.dca.ga.gov). Table of Contents Relevant Law 3 Entering into a Lease and Other Tenancy Issues 5 1. Submitting a Rental Application 5 2. Reviewing and Signing a Lease 5 3. Problems During a Lease: 10 4. -

An Introduction to Social Housing, Second Edition

An Introduction to Social Housing Prelims.qxd 1/21/05 11:30 AM Page ii To my wife, Marlena, with all my love. Prelims.qxd 1/21/05 11:30 AM Page iii An Introduction to Social Housing Second edition PAUL REEVES MA(CANTAB) MCIH PGCE(HE) MCMI AMSTERDAM BOSTON HEIDELBERG LONDON NEW YORK OXFORD PARIS SAN DIEGO SAN FRANCISCO SINGAPORE SYDNEY TOKYO Prelims.qxd 1/21/05 11:30 AM Page iv Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann Linacre House, Jordan Hill, Oxford OX2 8DP 30 Corporate Drive, Burlington, MA 01803 First published in 1996 by Arnold Second edition 2005 Copyright © 1996, P. Reeves; © 2005, Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any material form (including photocopying or storing in any medium by electronic means and whether or not transiently or incidentally to some other use of this publication) without the written permission of the copyright holder except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 or under the terms of a licence issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency Ltd, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4LP, England. Applications for the copyright holder’s written permission to reproduce any part of this publication should be addressed to the publisher Permissions may be sought directly from Elsevier’s Science and Technology Rights Department in Oxford, UK: phone: (44) (0) 1865 843830; fax: (44) (0) 1865 853333; e-mail: [email protected]. You may also complete your request on-line via the Elsevier Science homepage (www.elsevier.com), by selecting ‘Customer Support’ and then ‘Obtaining Permissions’ ISBN 0 7506 63936 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library For information on all Butterworth-Heinemann publications visit our website at http://bookselsevier.com Typeset by Charon Tec Pvt.