Law and the Presidency Peter M. Shane Spring, 2015 Supplementary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Select List of Collection Processed by Craig Moore

Select List of Collection Processed by Craig Moore Record Group 1, Colonial Government A Guide to the Colonial Papers, 1630-1778 Record Group 3, Office of the Governor A Guide to the Executive Papers of Governor Patrick Henry, 1776-1779 A Guide to the Executive Papers of Governor Thomas Jefferson, 1779-1781 A Guide to the Executive Papers of Governor Benjamin Harrison, 1781-1784 A Guide to the Executive Papers of Acting Governor William Fleming, 1781 A Guide to the Executive Papers of Governor Thomas Nelson, Jr., 1781 A Guide to the Executive Papers of Governor Patrick Henry, 1784-1786 A Guide to the Executive Papers of Governor Edmund Randolph, 1786-1788 A Guide to the Executive Papers of Governor Beverley Randolph, 1788-1791 A Guide to the Executive Papers of Governor Henry Lee, 1791-1794 A Guide to the Executive Papers of Governor Robert Brooke, 1794-1796 A Guide to the Executive Papers of Governor James Wood, 1796-1799 A Guide to the Executive Papers of Governor James Monroe, 1799-1802 A Guide to the Executive Papers of Governor John Page, 1802-1805 A Guide to the Executive Papers of Governor William H. Cabell, 1805-1808 A Guide to the Executive Papers of Governor John Tyler, 1808-1811 A Guide to the Executive Papers of Governor James Monroe, 1811 A Guide to the Executive Papers of Governor George William Smith, 1811-1812 A Guide to the Executive Papers of Governor James Barbour, 1812-1814 A Guide to the Executive Papers of Governor Wilson Cary Nicholas, 1814-1816 A Guide to the Executive Papers of Governor James Patton Preston, 1816-1819 A Guide to the Executive Papers of Governor Thomas Mann Randolph, 1819-1822 A Guide to the Executive Papers of Governor James Pleasants, 1822-1825 A Guide to the Executive Papers of Governor John Tyler, 1825-1827 A Guide to the Executive Papers of Governor William B. -

The Papers of Thomas Jefferson: Retirement

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. CONTENTS Foreword vii Acknowledgments ix Editorial Method and Apparatus xiii Maps xliii Illustrations li Jefferson Chronology 2 l l k l ' l 1818 From Henry Dearborn, 22 April 3 From Gamaliel H. Ward, 22 April 4 From John Wood, 22 April 6 From John Rhea, 23 April 7 From Stephen Cathalan, 25 April 8 From Thomas Appleton, 29 April 11 Matthew Pate’s Survey of Eighteen-Acre Tract Adjacent to Poplar Forest, 30 April 11 Thomas Eston Randolph’s Memorandum on Wheat Delivered to Thomas Jefferson, [April?] 13 To Wilson Cary Nicholas, 1 May 14 From Stephen Cathalan, 2 May, enclosing Invoice of Items Shipped, 28 April 14 To John Wayles Eppes, 3 May 17 From Patrick Gibson, 4 May 18 From Beverly Waugh, 5 May 19 From Benjamin O. Tyler, 6 May 20 Salma Hale’s Visit to Monticello 22 I. Salma Hale to David Hale, 5 May, with postscript, 7 May 22 II. Salma Hale to William Plumer, 8 May 24 III. Salma Hale to Arthur Livermore, 16 May 24 IV. Salma Hale’s Notes on his Visit to Monticello, [after 1818] 26 From Mordecai M. Noah, 7 May 30 From John Vaughan, 7 May 31 From William F. Gray, 8 May 32 To Lewis D. Belair, 10 May 32 To Mathew Carey, 10 May 33 To Richard Claiborne, 10 May 33 To Ferdinando Fairfax, 10 May 34 xxvii For general queries, contact [email protected] © Copyright, Princeton University Press. -

The Radical Democratic Thought of Thomas Jefferson: Politics, Space, & Action

The Radical Democratic Thought of Thomas Jefferson: Politics, Space, & Action Dean Caivano A Dissertation Submitted To The Faculty Of Graduate Studies In Partial Fulfillment Of The Requirements For The Degree Of Doctor Of Philosophy Graduate Program in Political Science York University Toronto, Ontario May 2019 © Dean Caivano, 2019 Abstract Thomas Jefferson has maintained an enduring legacy in the register of early American political thought. As a prolific writer and elected official, his public declarations and private letters helped to inspire revolutionary action against the British monarchy and shape the socio-political landscape of a young nation. While his placement in the American collective memory and scholarship has remained steadfast, a crucial dimension of his thinking remains unexplored. In this dissertation, I present a heterodox reading of Jefferson in order to showcase his radical understanding of politics. Although Jefferson’s political worldview is strikingly complex, marked by affinities with liberal, classical republican, Scottish, and Christian modes of thought, this interpretation reveals the radical democratic nature of his project. Primarily, this dissertation expands the possibilities of Jefferson’s thought as explored by Hannah Arendt and other thinkers, such as Richard K. Matthews and Michael Hardt. Drawing from these explicitly radical readings, I further dialogue with Jefferson’s thought through extensive archival research, which led me to engage in the theoretical and historical sources of inspiration that form and underscore his thinking. In so doing, I offer a new reading of Jefferson’s view on politics, suggesting that there contains an underlying objective, setting, and method to his unsystematic, yet innovative prescriptions concerning democracy. -

Documenting Women's Lives

Documenting Women’s Lives A Users Guide to Manuscripts at the Virginia Historical Society A Acree, Sallie Ann, Scrapbook, 1868–1885. 1 volume. Mss5:7Ac764:1. Sallie Anne Acree (1837–1873) kept this scrapbook while living at Forest Home in Bedford County; it contains newspaper clippings on religion, female decorum, poetry, and a few Civil War stories. Adams Family Papers, 1672–1792. 222 items. Mss1Ad198a. Microfilm reel C321. This collection of consists primarily of correspondence, 1762–1788, of Thomas Adams (1730–1788), a merchant in Richmond, Va., and London, Eng., who served in the U.S. Continental Congress during the American Revolution and later settled in Augusta County. Letters chiefly concern politics and mercantile affairs, including one, 1788, from Martha Miller of Rockbridge County discussing horses and the payment Adams's debt to her (section 6). Additional information on the debt appears in a letter, 1787, from Miller to Adams (Mss2M6163a1). There is also an undated letter from the wife of Adams's brother, Elizabeth (Griffin) Adams (1736–1800) of Richmond, regarding Thomas Adams's marriage to the widow Elizabeth (Fauntleroy) Turner Cocke (1736–1792) of Bremo in Henrico County (section 6). Papers of Elizabeth Cocke Adams, include a letter, 1791, to her son, William Cocke (1758–1835), about finances; a personal account, 1789– 1790, with her husband's executor, Thomas Massie; and inventories, 1792, of her estate in Amherst and Cumberland counties (section 11). Other legal and economic papers that feature women appear scattered throughout the collection; they include the wills, 1743 and 1744, of Sarah (Adams) Atkinson of London (section 3) and Ann Adams of Westham, Eng. -

History and Facts on Virginia

History and Facts on Virginia Capitol Building, Richmond 3 HISTORY AND FACTS ON VIRGINIA In 1607, the first permanent English settlement in America was established at Jamestown. The Jamestown colonists also established the first representative legislature in America in 1619. Virginia became a colony in 1624 and entered the union on June 25, 1788, the tenth state to do so. Virginia was named for Queen Elizabeth I of England, the “Virgin Queen” and is also known as the “Old Dominion.” King Charles II of England gave it this name in appreciation of Virginia’s loyalty to the crown during the English Civil War of the mid-1600s. Virginia is designated as a Commonwealth, along with Kentucky, Massachusetts, and Pennsylvania. In 1779, the capital was relocated from Williamsburg to Richmond. The cornerstone for the Virginia Capitol Building was laid on August 18, 1785, and the building was completed in 1792. Modeled after the Maison Carrée at Nîmes, France, the Capitol was the first public building in the United States to be built using the Classical Revival style of architecture. Thomas Jefferson designed the central section of the Capitol, including its most outstanding feature: the interior dome, which is undetectable from the exterior. The wings were added in 1906 to house the Senate and House of Delegates. In 2007, in time to receive the Queen of England during the celebration of the 400th anniversary of the Jamestown Settlement, the Capitol underwent an extensive restoration, renovation and expansion, including the addition of a state of the art Visitor’s Center that will ensure that it remains a working capitol well into the 21st Century. -

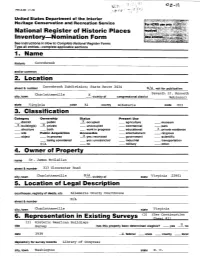

Carrsbrook Andlor Common 2

United States Department of the Interior Heritage Conservation and Recreation Service National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination Form See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries-complete applicable sections 1. Name historic Carrsbrook andlor common 2. Location Carrsbrook Subdivision; State Route 1424 street & number N/A not for publication Charlottesville X ... Seventh (J. Kenneth city, town -vlclnlty of congressional district Robinson) state Virginia code 51 County Albemarle code 003 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use -district -public X occupied -agriculture -museum X building@) X private -unoccupied -commercial -park -structure -both -work in progress -educational X private residence -site Public Acquisition Accessible -entertainment -religious -object -in process 2yes: restricted -government -scientific -being considered - yes: unrestricted -industrial -transportation N /A -no -militarv -other: 4. Owner of Property name Dr. James McClellan street & number 313 Gloucester Road citv, town Charlottesville N/Avicinitv of state Virginia 22901 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Albemarle County Courthouse N/A street & number city,town Charlottesville state Virginia (2) (See Continuation 6. Representation in Existing Surveys Sheet #1) (1) Historic American Buildings X title Survey has this property been determined eiegibie? -yes -no date 1939 _X federal -state -county -local deDositow for survev records Librarv of Conaress city, town Washington state D. C. Condition Check one Check one -excellent -deteriorated X unaltered original site 2~good -ruins -altered -moved date N/A -fair -unexposed Describe the present and original (if known) physical appearance Carrsbrook was once part of a thousand-acre tract of land. Sited high on a bluff, the house was provided with sweeping vistas of the Rivanna River Valley and Southwest Mountains. -

Pavilion Vii

PAVILION VII HISTORY AUTHORIZATION AND NEGOTIATION FOR CONSTRUCTING PAVILION VII he germ of the plan of Pavilion VII can be detected in a letter Jefferson wrote to Virginia Legislator Littleton Waller Tazewell on January 5, 1805, from the Presi- T dent's House in Washington 1. In his letter, which was in response to an inquiry concerning a proposal for a university that Tazewell wished to submit to the General As- sembly, Jefferson wrote: Large houses are always ugly, inconvenient, exposed to the accident of fire, and bad in case of infection. A plain small house for the school & lodging of each professor is best, these connected by covered ways out of which the rooms of the students should open. These may then be built only as they shall be wanting. In fact a university should not be a house but a village. 2 Nothing came of Tazewell's proposal, but five years later Jefferson had the occa- sion to refine his ideas when he responded to another inquiry, this time from Hugh White, a trustee of the East Tennessee College: I consider the common plan followed in this country of making one large and expensive building, as unfortunately erroneous. It is infinitely better to erect a small and separate lodge for each separate professorship, with only a hall below for his class, and two chambers above for himself; joining these lodges by bar- racks for a certain portion of the students, opening into a covered way to give a dry communication between all the schools. The whole of these arranged around an open square of grass and trees, would make it, what it should be in fact, an academical village. -

Guide and Inventories to Manuscripts in the Special

GUIDE AND INVENTORIES TO MANUSCRIPTS IN THE SPECIAL COLLECTIONS SECTION JOHN D. ROCKEFELLER, JR. LIBRARY COLONIAL WILLIAMSBURG FOUNDATION TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. ELIZABETH JACQUELIN AMBLER PAPERS. DMS1954.5 2. HELEN M. ANDERSON PAPERS. MS1989.13 3. JAMES ANDERSON ACCOUNT BOOKS. MS1962.2 4. ROBERT ANDERSON PAPERS. MS1972.2 5. ROBERT ANDERSON PAPERS, ADDITION ONE. MS1978.1 6. L'ARCHITECTURE OU L'ART DE BIEN BASTIR. MS1981.13 7. ARITHMETIC EXERCISE BOOK. MS1965.6 8. EDMUND BAGGE ACCOUNT BOOK. MS1941.9 9. BAYLOR FAMILY PAPERS. MS1959.1 10. BLATHWAYT PAPERS. MS1946.2 11. BOOKPLATE COLLECTION. MS1990.1 12. THOMAS T. BOULDIN PAPERS. MS1987.3 13. BOWYER-HUBARD PAPERS. MS1929.1 14. WILLIAM BROGRAVE ESTATE AUCTION ACCOUNT BOOK. MS1989.7 15. BURWELL PAPERS. MS1964.4 16. NATHANIEL BURWELL LEDGER AND PAPERS. MS1981.12 17. DR. SAMUEL POWELL BYRD PAPERS. MS1939.4 18. WILLIAM BYRD II PAPERS. MS1940.2 19. DR. JAMES CARTER INVOICE BOOK. MS1939.8 20. ROBERT CARTER LETTER BOOKS. MS1957.1 21. ROBERT CARTER III WASTE BOOK. MS1957.2 22. COACH AND CARRIAGE PAPERS. MS1980.2 23. COACH DRAWINGS. MS1948.3 24. ROBERT SPILSBE COLEMAN ARITHMETIC EXERCISE BOOK. MS1973.4 80. ROSE MUSIC BOOKS. MS1973.3 81. SERVANTS' INDENTURES. MS1970.3 82. ANDREW SHEPHERD ACCOUNT BOOK. MS1966.1 83. DAVID SHEPHERD CIPHERING BOOK. MS1971.3 84. THOMAS H. SHERWOOD LETTERS. MS1983.4 85. (COLLECTION RETURNED TO SHIRLEY PLANTATION) 86. SHOE DEALER'S ACCOUNT BOOK. MS1950.5 87. LT. COL. JOHN GRAVES SIMCOE PAPERS. MS1930.6 88. SMITH-DIGGES PAPERS. MS1931.7 89. TURNER SOUTHALL RECEIPT BOOK. MS1931.3 90. WILLIAM SPENCER DIARY. -

National Register of Historic Places Lnventory;...Nomination Form 1

7 . ;> . ., : Oz-I\ 'V'L \< ' FHR-&-300 (11-78) .~-1 -7 _,' ,:..: ,/ ''i. ,:' t,l f, f' ,. ' ~ . United States Department of the Interior Hei'itage Conservation and Recreation Service National Register of Historic Places lnventory;....Nomination Form See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries-complete applicable sections 1. Name historic Carrsbrook and/or common 2. Location Carrsbrook Subdivision; State Route i424 street & number Ni.A_ not for publication Charlottesville Seventh (J. Kenneth city, town ~ vicinity of congressional district Robinson) state Virginia code 51 county Albemarle code 003 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use _district _public ___K_ occupied _ agriculture _museum i building(s) iprivate _ unoccupied _ commercial _park _structure _both _ work in progress _ educational --1L private residence _site Public Acquisition Accessible _ entertainment __ religious _object _in process ~ yes: restricted · _ government _ scientific _ being considered ~ yes: unrestricted _ industrial _ transportation N/A _no _military _other: 4. Owner of Property name Dr. James McClellan street & number 313 Gloucester Road city, town Charlottesville N / A vicinity of state Virginia 22901 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Albemarle County Courthouse N/A street & number city, town Charlottesville state Virginia 6. Representation in Existing Surveys (2) (See Continuation Sheet #ll (1) Historic American Buildings !Ille Survey has this property been determined elegible? _ yes ~ no date 1939 --1l. federal _ state _ county _ local depository for survey records Library of Congress city, town Washington state D. C. 7. Description Condition Check one Check one __ excellent __ deteriorated __K_ unaltered -1L original site N/A __K_good __ ruins __ altered __ moved date --~----------- __ fair __ unexposed Describe the present and original (if known) physical appearance Carrsbrook was once part of a thousand-acre tract of land. -

British Journal of American Legal Studies

Birmingham City School of Law BritishBritish JoJournalurnal ofof British Journal of American Legal Studies | Volume 7 Issue 1 7 Issue Legal Studies | Volume British Journal of American British Journal of American Legal Studies | Volume 8 Issue 1 8 Issue Legal Studies | Volume British Journal of American AmericanAmerican LegalLegal StudiesStudies VolumeVolume 87 IssueIssue 11 SpringSpring 20192018 ARTICLES ARTICLES Founding-Era Socialism: The Original Meaning of the Constitution’s Postal Clause Robert G. Natelson Secularizing a Religious Legal System: Ecclesiastical Jurisdiction inToward Early EighteenthNatural Born Century Derivative England Citizenship Troy L. JohnHarris Vlahoplus SanctuaryFelix Frankfurter Cities: Aand Study the inLaw Modern Nullification LorraineThomas Marie A. Halper Simonis Fundamental Rights in Early American Case Law: 1789-1859 Nicholas P. Zinos Solving Child Statelessness: Disclosure,The Holmes Reporting, Truth: Toward and Corporatea Pragmatic, Responsibility Holmes-Influenced Conceptualization Mark K. Brewer & of the Nature of Truth Sue TurnerJared Schroeder Declaration of War: A Dead Letter or An Invitation to Struggle? Thomas Halper Acts of State, State Immunity, and Judicial Review in the United States Zia Akthar Normative and Institutional Dimensions of Rights’ Adjudication Around the World Pedro Caro de Sousa BRITISH JOURNAL OF AMERICAN LEGAL STUDIES BIRMINGHAM CITY UNIVERSITY LAW SCHOOL THE CURZON BUILDING, 4 CARDIGAN STREET, BIRMINGHAM, B4 7BD, UNITED KINGDOM ISSNISSN 2049-40922049-4092 (Print)(Print) British Journal of American Legal Studies Editor-in-Chief: Dr Anne Richardson Oakes, Birmingham City University. Deputy Editors Dr Ilaria Di-Gioia, Birmingham City University. Dr Friso Jansen, Birmingham City University. Associate Editors Dr Sarah Cooper, Birmingham City University. Prof Haydn Davies, Birmingham City University. Prof Julian Killingley, Birmingham City University Dr Alice Storey, Birmingham City University Dr Amna Nazir, Birmingham City University Prof Jon Yorke, Birmingham City University. -

The Papers of Thomas Jefferson

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. CONTENTS Foreword vii Acknowledgments ix Editorial Method and Apparatus xi Maps xli Illustrations xlix Jefferson Chronology 2 l l k l ' l 1817 To Thomas Cooper, 1 September 3 From Joseph Coppinger, 2 September 5 From Hezekiah Niles, 2 September 6 From Thomas Branagan, 3 September 7 From John Wayles Eppes, 3 September 7 To John Adams, 8 September 8 Bill for Establishing Elementary Schools, [ca. 9 September] 10 To Joseph C. Cabell, 9 September 15 To Eleuthère I. du Pont de Nemours, 9 September 16 From William Wirt, 9 September 17 To Joseph C. Cabell, 10 September 18 To George Flower, 12 September 19 From John Woodson, 12 September 21 To John Martin Baker, 14 September 22 From Tadeusz Kosciuszko, 15 September 23 From Thomas Cooper, 16 September 25 From Thomas Cooper, 17 September 28 To Patrick Gibson, 18 September 29 To Samuel J. Harrison, enclosing Memorandum on Wine, 18 September 29 To James Newhall, 18 September 31 From Sloan & Wise, 18 September 31 From Thomas Cooper, 19 September 32 From William Bentley, 20 [September] 34 From José Corrêa da Serra, 20 September 35 From Benjamin W. Crowninshield, 20 September 36 From Alexander Garrett and Valentine W. Southall, 20 September 36 From Joshua Stow, 20 September 37 From Samuel McDowell Reid, 22 September 38 xxv For general queries, contact [email protected] © Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. -

Maryland Historical Magazine, 1968, Volume 63, Issue No. 4

T General Samuel Smith and the Election of 1800 Frank A. Cassell The Vestries and Morals in Colonial Maryland Gerald E. Hartdagen The Last Great Conclave of the Whigs Charles R. Schultz A QUARTERLY PUBLISHED BY THE MARYLAND HISTORICAL SOCIETY GOVERNING COUNCIL OF THE SOCIETY COLONEL WILLIAM BAXTER, President HON. FREDERICK W. BRUNE, Past President CHARLES P. CRANE, Membership Miss RHODA M. DORSEY^ Publications C. A. PORTER HOPKINS, Vice President SAMUEL HOPKINS, Treasurer BRYDEN B. HYDE, Vice President FRANCIS H. JENCKS, Gallery H. H. WALKER LEWIS, Recording Secretary CHARLES L. MARBURG, Athenaeum WILLIAM B. MARYE, Corresponding Secretary ROBERT G. MERRICK, Finance J. GILMAN D'ARCY PAUL, Vice President A. L. PENNIMAN, JR., Building THOMAS G. PULLEN, JR., Education HON. GEORGE L. RADCLIFFE, Chairman of the Council RICHARD H. RANDALL, SR., Maritime MRS. W. WALLACE SYMINGTON, JR., Women's DR. HUNTINGTON WILLIAMS, Library HAROLD R. MANAKEE, Director BOARD OF EDITORS DR. RHODA M. DORSEY, Chairman DR. JACK P. GREENE DR. AUBREY C. LAND DR. BENJAMIN QUARLES DR. MORRIS L. RADOFF MR. A. RUSSELL SLAGLE DR. RICHARD WALSH MARYLAND HISTORICAL MAGAZINE VOL. 63, No. 4 DECEMBER, 1968 CONTENTS PAGE General Samuel Smith and the Election of 1800 Frank A. Cassell 341 The Vestries and Morals in Colonial Maryland Gerald E. Hartdagen 360 The Last Great Conclave of the Whigs Charles R. Schultz 379 Sidelights Charles Town, Prince George's First County Seat Louise Joyner Hienton 401 Master's Theses and Doctoral Dissertations in Maryland, H istory 412 Compiled by Dorothy M. Brown and Richard R. Duncan Bibliographical Notes Edited by Edward G.