Cused on the Mainland, Pan-Chinese Or Even Global Market

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The New Hong Kong Cinema and the "Déjà Disparu" Author(S): Ackbar Abbas Source: Discourse, Vol

The New Hong Kong Cinema and the "Déjà Disparu" Author(s): Ackbar Abbas Source: Discourse, Vol. 16, No. 3 (Spring 1994), pp. 65-77 Published by: Wayne State University Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/41389334 Accessed: 22-12-2015 11:50 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/ info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Wayne State University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Discourse. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 142.157.160.248 on Tue, 22 Dec 2015 11:50:37 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions The New Hong Kong Cinema and the Déjà Disparu Ackbar Abbas I For about a decade now, it has become increasinglyapparent that a new Hong Kong cinema has been emerging.It is both a popular cinema and a cinema of auteurs,with directors like Ann Hui, Tsui Hark, Allen Fong, John Woo, Stanley Kwan, and Wong Rar-wei gaining not only local acclaim but a certain measure of interna- tional recognitionas well in the formof awards at international filmfestivals. The emergence of this new cinema can be roughly dated; twodates are significant,though in verydifferent ways. -

Old Town Central - Enrich Visitor’S Experience

C&WDC WG on DC Affairs Paper No. 2/2017 OldOld TTownown CCentralentral 1 Old Town Central - Enrich Visitor’s Experience A contemporary lifestyle destination and a chronicle of how Arts, Heritage, Creativity, and Dining & Entertainment evolved in the city Bounded by Wyndham Street, Caine Road, Possession Street and Queen’s Road Central Possession Street Queen’s Road Central Caine Road Wyndham Street Key Campaign Elements DIY Walking Guide Heritage & Art History Integrated Marketing Local & Overseas Publicity Launch Ceremony City Ambience Tour Products 3 5 Thematic ‘Do-It-Yourself’ Routes For visitors to explore the abundant treasure according to their own interests and pace. Heritage & Dining & Art Treasure Hunt All-in-one History Entertainment Possession Street, Tai Ping Shan PoHo, Upper PMQ, Hollywood Graham market & Best picks Street, Lascar Row, Road, Peel Street, around, LKF, from each Man Mo Temple, StauntonS Street & Aberdeen Street SoHo, Ladder Street, around route Tai Kwun 4 Sample route: All-in-one Walking Tour Route for busy visitors 1. Possession Street (History) 1 6: Gough Street & Kau U Fong (Creative & Design – Designer stores, boutiques 2 4: Man Mo Temple Dining – Local food stalls & (Heritage - Declared International cuisine) 2: POHO - Tai Ping Shan Street (Local Monument ) culture – Temples / Stores/ Restaurant) 6 (Art & Entertainment – Galleries / 4 Street Art/ Café ) 3 7 5 7: Pak Tsz Lane Park 5: PMQ (History) 3: YMCA Bridges Street Centre & ( Heritage - 10: Pottinger Ladder Street Arts & Dining – Galleries, Street -

The Studies of HKIFF: an Overview of a Burgeoning Field of Its Establishment in the Current Years

The studies of Hong Kong International Film Festival (HKIFF) : Title an overview of a burgeoning field of its establishment in the current years Author(s) Law, Pik-yu Law, P. E.. (2015). The studies of Hong Kong International Film Festival (HKIFF) : an overview of a burgeoning field of its Citation establishment in the current years. (Thesis). University of Hong Kong, Pokfulam, Hong Kong SAR. Issued Date 2015 URL http://hdl.handle.net/10722/223429 The author retains all proprietary rights, (such as patent rights) and the right to use in future works.; This work is licensed under Rights a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. The Studies of HKIFF: An Overview of a Burgeoning Field of its establishment in the current years The University of Hong Kong Department of Sociology Assignment / Essay Cover Sheet1 Programme Title: Master of Social Sciences in Media, Culture and Creative Cities – MSocSc(MCCC) Title of Course: SOCI8030 Capstone Project Course Code: SOCI8030 Title of Assignment / Essay: The Studies of Hong Kong International Film Festival (HKIFF): An overview of a Burgeoning Field of its establishment in the current years Student Name: LAW, Pik Yu Eugenia Student Number: 2013932305 Year of Study: Year 2 Date of Resubmission2: Plagiarism Plagiarism is the presentation of work which has been copied in whole or in part from another person’s work, or from any other source such as the Internet, published books or periodicals without due acknowledgement given in the text. Where there are reasonable grounds for believing that cheating has occurred, the action that may be taken when plagiarism is detected is for the staff member not to mark the item of work and to report or refer the matter to the Department. -

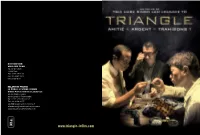

DP TRIANGLE.Indd

DISTRIBUTION WILD SIDE FILMS 42, rue de Clichy 75009 Paris Tél : 01 42 25 82 00 Fax : 01 42 25 82 10 www.wildside.fr RELATIONS PRESSE LE PUBLIC SYSTEME CINEMA Céline Petit & Annelise Landureau 40, rue Anatole France 92594 Levallois-Perret cedex Tel : 01 41 34 23 50 / 22 01 Fax : 01 41 34 20 77 [email protected] [email protected] www.lepublicsystemecinema.com www.triangle-lefi lm.com CADAVRE EXQUIS : Jeu créé par les surréalistes en 1920 qui consiste à faire composer une phrase, ou un dessin, par plusieurs personnes sans qu’aucune d’elles puisse tenir compte de la collaboration ou des collaborations précédentes. En règle générale un cadavre exquis est une histoire commencée par une personne et terminée par plusieurs autres. Quelqu’un écrit plusieurs lignes puis donne le texte à une autre personne qui ajoute quelques lignes et ainsi de suite jusqu’à ce que quelqu’un décide de conclure l’histoire. DISTRIBUTION STOCK Wild Side Films Distribution Service Tél : 01 42 25 82 00 STOCKS COPIES ET PUBLICITÉ Fax : 01 42 25 82 10 Grande Région Ile-de-France www.wildside.fr 24, Route de Groslay 95204 Sarcelles WILD SIDE FILMS DIRECTION DE LA DISTRIBUTION présente Marc-Antoine Pineau COPIES Tél. : 01 34 29 44 21 [email protected] Fax : 01 39 94 11 48 [email protected] Dossier de presse imprimé en papier recyclé PROGRAMMATION Philippe Lux PUBLICITÉ [email protected] Tél. : 01 34 29 44 26 Fax : 01 34 29 44 09 [email protected] MÉDIAS Le premier film réalisé sur le principe du jeu du cadavre exquis Christophe Laduche par les trois maîtres du cinéma de Hong Kong [email protected] LYON 25, avenue Beauregard 69150 Decines DIRECTRICE TECHNIQUE 35MM Brigitte Dutray Tél. -

Donnie Yen's Kung Fu Persona in Hypermedia

Studies in Media and Communication Vol. 4, No. 2; December 2016 ISSN 2325-8071 E-ISSN 2325-808X Published by Redfame Publishing URL: http://smc.redfame.com Remediating the Star Body: Donnie Yen’s Kung Fu Persona in Hypermedia Dorothy Wai-sim Lau1 113/F, Hong Kong Baptist University Shek Mun Campus, 8 On Muk Street, Shek Mun, Shatin, Hong Kong Correspondence: Dorothy Wai-sim Lau, 13/F, Hong Kong Baptist University Shek Mun Campus, 8 On Muk Street, Shek Mun, Shatin, Hong Kong. Received: September 18, 2016 Accepted: October 7, 2016 Online Published: October 24, 2016 doi:10.11114/smc.v4i2.1943 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.11114/smc.v4i2.1943 Abstract Latest decades have witnessed the proliferation of digital media in Hong Kong action-based genre films, elevating the graphical display of screen action to new levels. While digital effects are tools to assist the action performance of non-kung fu actors, Dragon Tiger Gate (2006), a comic-turned movie, becomes a case-in-point that it applies digitality to Yen, a celebrated kung fu star who is famed by his genuine martial dexterity. In the framework of remediation, this essay will explore how the digital media intervene of the star construction of Donnie Yen. As Dragon Tiger Gate reveals, technological effects work to refashion and repurpose Yen’s persona by combining digital effects and the kung fu body. While the narrative of pain and injury reveals the attempt of visual immediacy, the hybridized bodily representation evokes awareness more to the act of representing kung fu than to the kung fu itself. -

Tsui Hark Ringo Lam Johnnie To

TSUI HARK LOUIS KOO A legendary producer and director, Tsui Hark is one of Hong Kong cinema’s most influential figures. A pioneer of the 80’s Hong Kong New — AH FAI Wave film movement, Tsui Hark immediately caught the attention of critics with his innovative style and techniques. “Butterfly Murders” Singer, actor, model – Louis Koo is one of Hong Kong’s most popular Chanteur, acteur, mannequin – Louis Koo est l’une des plus grandes (1979) and “Dangerous Encounters: 1st Kind”(1980) pushed the boundary of Hong Kong genre films as well as the limit of the censors. celebrities. He began his film career in the mid-90’s and has acted in stars de Hong Kong. Il commence sa carrière au milieu des années 90 Following the creation of Film Workshop in 1984, he directed and produced a series of successful commercial films that initiated the so-called over 40 movies such as Wilson Yip’s “Bullet Over Summer”(1999), Tsui et joue dans plus de 40 films, dont « Bullets Over Summer » (1999) de “golden era” of Hong Kong cinema. Films including “A Chinese Ghost Story”(1987), “Swordsman”(1990), and “Once Upon A Time In China” Hark’s “Legend of Zu 2”(2001) and Derek Yee’s “Lost In Time”(2003). Wilson Yip, « La Légende de Zu 2 » (2001) de Tsui Hark et « Lost In (1991) established Tsui Hark's dominance across Asia. After directing two films in Hollywood, he returned to Hong Kong in the mid-90’s Over the past couple of years, he has forged a close working relationship Time » (2003) de Derek Yee. -

1 “Ann Hui's Allegorical Cinema” Jessica Siu-Yin Yeung to Cite This

This is the version of the chapter accepted for publication in Cultural Conflict in Hong Kong: Angles on a Coherent Imaginary published by Palgrave Macmillan https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-981-10-7766-1_6 Accepted version downloaded from SOAS Research Online: http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/34754 “Ann Hui’s Allegorical Cinema” Jessica Siu-yin Yeung To cite this article: By Jessica Siu-yin Yeung (2018) “Ann Hui’s Allegorical Cinema”, Cultural Conflict in Hong Kong: Angles on a Coherent Imaginary, ed. Jason S. Polley, Vinton Poon, and Lian-Hee Wee, 87-104, Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018. Allegorical cinema as a rhetorical approach in Hong Kong new cinema studies1 becomes more urgent and apt when, in 2004, the Closer Economic Partnership Arrangement (CEPA) begins financing mainland Chinese-Hong Kong co-produced films.2 Ackbar Abbas’s discussion on “allegories of 1997” (1997, 24 and 16–62) stimulates studies on Happy Together (1997) (Tambling 2003), the Infernal Affairs trilogy (2002–2003) (Marchetti 2007), Fu Bo (2003), and Isabella (2006) (Lee 2009). While the “allegories of 1997” are well- discussed, post-handover allegories remain underexamined. In this essay, I focus on allegorical strategies in Ann Hui’s post-CEPA oeuvre and interpret them as an auteurish shift from examinations of local Hong Kong issues (2008–2011) to a more allegorical mode of narration. This, however, does not mean Hui’s pre-CEPA films are not allegorical or that Hui is the only Hong Kong filmmaker making allegorical films after CEPA. Critics have interpreted Hui’s films as allegorical critiques of local geopolitics since the beginning of her career, around the time of the Sino-British Joint Declaration in 1984 (Stokes and Hoover 1999, 181 and 347 note 25), when 1997 came and went (Yau 2007, 133), and when the Umbrella Movement took place in 2014 (Ho 2017). -

IFFAM 2943 – East & West Masterpieces on the Big Screen

SUPPLEMENT THU 07.12.2017 SHOWING INSIDE Crossfire Special Presentation Flying Daggers FAQs II Int’l Film Festival EAST & WEST MASTERPIECES ON THE BIG SCREEN he Crossfire feature of the IFFAM, described by organizers as a “retrospective” element of the festival, will showcase six master films selected by renowned filmmakers. From the black and white motion pictures of the 1940s to Kubrick’s sci-fi masterpiece “2001: Space Odyssey” of the 60s and the psychological thriller “Silence of the Lambs”, the genre films hail from THollywood and Asia, the latter represented with seminal works from Kurosawa, Johnnie To and Derek Yee. International Film Festival & Awards Macao CROSSFIRE: A RETROSPECTIVE OF CINEMA FROM KUBRICK TO KUROSAWA The Crossfire feature of the IFFAM will showcase six master films selected by renowned filmmakers. The pictures will be shown on the big screen at The Cinematheque Passion, from December 8 to 12 ONE NITE IN MONGKOK Mongkok, Hong Kong: a densely populated hot- KIND HEARTS AND CORONETS MAD DETECTIVE bed of criminal activity. Mainland Chinese farm Hotshot Inspector Ho seeks out his former boss Bun boy Lai Fu is a hired killer who enters the neon-lit English actors Dennis Price and Sir Alec Guinness underbelly of this infamous district. When he res- star in this 1949 black comedy. Price plays the for help in cracking a serial murder case. Bun, a gifted criminal profiler, went mad years ago and now lives cues a call girl from gangsters, the two must go lead role of Louis d’Ascoyne Mazzini, ninth in line on the run from policemen and triads alike. -

An Interview with Ann Hui Visible Secrets: Hong Kong's Women

An Interview with Ann Hui Visible Secrets: Hong Kong’s Women Filmmakers Your 21st century films are quite eclectic. What has driven your choice of projects in recent times? I shot Visible Secrets after two years' teaching and I thought, first, I'd better do a film that was marketable. My first film is also a thriller and I thought it was fun to revisit old grounds. Then followed a film which I was really interested in making (July Rhapsody ), I thought I would never be able to raise funds for it but surprisingly it was accepted by the investor, so I made it. And so forth and so on... alternately, making films I really want to make and some I could just make so as to survive in the industry. Could you talk a little about The Way We Are and Night and Fog? These films seem quite different stylistically; one very much informed by social realism and the other more melodramatic, yet each seems perfect for its subject matter. What made you select these different approaches to the setting of Tin Shui Wai? The Way We Are was initially planned as a D.V. affair since I couldn’t find the money for Night and Fog . It's also initially not about Tin Shui Wai but I decided to transport the whole setting to Tin Shui Wai. The script was already written 7 or 8 years ago about another housing estate but since I knew Tin Shui Wai well, and the lifestyle of all these housing areas are about the same, I thought it would be okay to transpose the whole story to the newest housing estate. -

List of Action Films of the 2010S - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

List of action films of the 2010s - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_action_films_of_the_2010s List of action films of the 2010s From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia This is an incomplete list, which may never be able to satisfy particular standards for completeness. You can help by expanding it (//en.wikipedia.org /w/index.php?title=List_of_action_films_of_the_2010s&action=edit) with reliably sourced entries. This is chronological list of action films originally released in the 2010s. Often there may be considerable overlap particularly between action and other genres (including, horror, comedy, and science fiction films); the list should attempt to document films which are more closely related to action, even if it bends genres. Title Director Cast Country Sub-Genre/Notes 2010 13 Assassins Takashi Miike Koji Yakusho, Takayuki Yamada, Yusuke Iseya Martial Arts[1] 14 Blades Daniel Lee Donnie Yen, Vicky Zhao, Wu Chun Martial Arts[2] The A-Team Joe Carnahan Liam Neeson, Bradley Cooper, Quinton Jackson [3] Alien vs Ninja Seiji Chiba Masanori Mimoto, Mika Hijii, Shuji Kashiwabara [4][5] Bad Blood Dennis Law Simon Yam, Bernice Liu, Andy On [6] Sorapong Chatree, Supaksorn Chaimongkol, Kiattisak Bangkok Knockout Panna Rittikrai, Morakot Kaewthanee [7] Udomnak Blades of Blood Lee Joon-ik Cha Seung-won, Hwang Jung-min, Baek Sung-hyun [8] The Book of Eli Albert Hughes, Allen Hughes Denzel Washington, Gary Oldman, Mila Kunis [9] The Bounty Hunter Andy Tennant Jennifer Aniston, Gerard Butler, Giovanni Perez Action comedy[10] The Butcher, the Chef and the Wuershan Masanobu Ando, Kitty Zhang, You Benchang [11] Swordsman Centurion Neil Marshall Michael Fassbender, Olga Kurylenko, Dominic West [12] City Under Siege Benny Chan [13] The Crazies Breck Eisner Timothy Olyphant, Radha Mitchell, Danielle Panabaker Action thriller[14] Date Night Shawn Levy Steve Carell, Tina Fey, Mark Wahlberg Action comedy[15] The Expendables Sylvester Stallone Sylvester Stallone, Jason Statham, Jet Li [16] Faster George Tillman, Jr. -

Recommended District Council Constituency Areas

District : Central and Western Recommended District Council Constituency Areas +/- % of Population Estimated Quota Code Recommended Name Boundary Description Major Estates/Areas Population (17,282) A01 Chung Wan 18,529 +7.22 N District Boundary 1. HOLLYWOOD TERRACE NE District Boundary E District Boundary SE Monmouth Path, Kennedy Road S Kennedy Road, Macdonnell Road Garden Road, Lower Albert Road SW Lower Albert Road, Wyndham Street Arbuthnot Road, Chancery Lane Old Bailey Street, Elgin Street Peel Street, Staunton Street W Staunton Street, Aberdeen Street Hollywood Road, Ladder Street Queen's Road Central, Cleverly Street Connaught Road Central NW Chung Kong Road A1 District : Central and Western Recommended District Council Constituency Areas +/- % of Population Estimated Quota Code Recommended Name Boundary Description Major Estates/Areas Population (17,282) A02 Mid Levels East 20,337 +17.68 N Chancery Lane 1. PINE COURT 2. ROBINSON HEIGHTS Arbuthnot Road, Wyndham Street 3. THE GRAND PANORAMA NE Wyndham Street, Lower Albert Road 4. TYCOON COURT E Lower Albert Road, Garden Road SE Garden Road S Garden Road, Robinson Road, Old Peak Road Hornsey Road SW Hornsey Road W Hornsey Road, Conduit Road, Robinson Road Seymour Road, Castle Road NW Castle Road, Caine Road, Chancery Lane Elgin Street, Old Bailey Street, Seymour Road Shing Wong Street, Staunton Street A2 District : Central and Western Recommended District Council Constituency Areas +/- % of Population Estimated Quota Code Recommended Name Boundary Description Major Estates/Areas Population -

Chapter One Introduction Chapter Two the 1920S, People and Weather

Notes Chapter One Introduction 1. Steve Tsang, ed., Government and Politics (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 1995); David Faure, ed., Society (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 1997); David Faure and Lee Pui-tak, eds., Economy (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2004); and David Faure, Colonialism and the Hong Kong Mentality (Hong Kong: Centre of Asian Studies, University of Hong Kong, 2003). 2. Cindy Yik-yi Chu, The Maryknoll Sisters in Hong Kong, 1921–1969: In Love with the Chinese (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004), book jacket. Chapter Two The 1920s, People and Weather 1. R. L. Jarman, ed., Hong Kong Annual Administration Reports 1841–1941, Archive ed., Vol. 4: 1920–1930 (Farnham Common, 1996), p. 26. 2. Ibid., p. 27. 3. S. G. Davis, Hong Kong in Its Geographical Setting (London: Collins, 1949), p. 215. 4. Vicariatus Apostolicus Hongkong, Prospectus Generalis Operis Missionalis; Status Animarum, Folder 2, Box 10: Reports, Statistics and Related Correspondence (1969), Accumulative and Comparative Statistics (1842–1963), Section I, Hong Kong Catholic Diocesan Archives, Hong Kong. 5. Unless otherwise stated, quotations in this chapter are from Folders 1–5, Box 32 (Kowloon Diaries), Diaries, Maryknoll Mission Archives, Maryknoll, New York. 6. Cindy Yik-yi Chu, The Maryknoll Sisters in Hong Kong, 1921–1969: In Love with the Chinese (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004), pp. 21, 28, 48 (Table 3.2). 210 / notes 7. Ibid., p. 163 (Appendix I: Statistics on Maryknoll Sisters Who Were in Hong Kong from 1921 to 2004). 8. Jean-Paul Wiest, Maryknoll in China: A History, 1918–1955 (Armonk: M.E.