Florida Historical Quarterly

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Many-Storied Place

A Many-storied Place Historic Resource Study Arkansas Post National Memorial, Arkansas Theodore Catton Principal Investigator Midwest Region National Park Service Omaha, Nebraska 2017 A Many-Storied Place Historic Resource Study Arkansas Post National Memorial, Arkansas Theodore Catton Principal Investigator 2017 Recommended: {){ Superintendent, Arkansas Post AihV'j Concurred: Associate Regional Director, Cultural Resources, Midwest Region Date Approved: Date Remove not the ancient landmark which thy fathers have set. Proverbs 22:28 Words spoken by Regional Director Elbert Cox Arkansas Post National Memorial dedication June 23, 1964 Table of Contents List of Figures vii Introduction 1 1 – Geography and the River 4 2 – The Site in Antiquity and Quapaw Ethnogenesis 38 3 – A French and Spanish Outpost in Colonial America 72 4 – Osotouy and the Changing Native World 115 5 – Arkansas Post from the Louisiana Purchase to the Trail of Tears 141 6 – The River Port from Arkansas Statehood to the Civil War 179 7 – The Village and Environs from Reconstruction to Recent Times 209 Conclusion 237 Appendices 241 1 – Cultural Resource Base Map: Eight exhibits from the Memorial Unit CLR (a) Pre-1673 / Pre-Contact Period Contributing Features (b) 1673-1803 / Colonial and Revolutionary Period Contributing Features (c) 1804-1855 / Settlement and Early Statehood Period Contributing Features (d) 1856-1865 / Civil War Period Contributing Features (e) 1866-1928 / Late 19th and Early 20th Century Period Contributing Features (f) 1929-1963 / Early 20th Century Period -

Wilderness on the Edge: a History of Everglades National Park

Wilderness on the Edge: A History of Everglades National Park Robert W Blythe Chicago, Illinois 2017 Prepared under the National Park Service/Organization of American Historians cooperative agreement Table of Contents List of Figures iii Preface xi Acknowledgements xiii Abbreviations and Acronyms Used in Footnotes xv Chapter 1: The Everglades to the 1920s 1 Chapter 2: Early Conservation Efforts in the Everglades 40 Chapter 3: The Movement for a National Park in the Everglades 62 Chapter 4: The Long and Winding Road to Park Establishment 92 Chapter 5: First a Wildlife Refuge, Then a National Park 131 Chapter 6: Land Acquisition 150 Chapter 7: Developing the Park 176 Chapter 8: The Water Needs of a Wetland Park: From Establishment (1947) to Congress’s Water Guarantee (1970) 213 Chapter 9: Water Issues, 1970 to 1992: The Rise of Environmentalism and the Path to the Restudy of the C&SF Project 237 Chapter 10: Wilderness Values and Wilderness Designations 270 Chapter 11: Park Science 288 Chapter 12: Wildlife, Native Plants, and Endangered Species 309 Chapter 13: Marine Fisheries, Fisheries Management, and Florida Bay 353 Chapter 14: Control of Invasive Species and Native Pests 373 Chapter 15: Wildland Fire 398 Chapter 16: Hurricanes and Storms 416 Chapter 17: Archeological and Historic Resources 430 Chapter 18: Museum Collection and Library 449 Chapter 19: Relationships with Cultural Communities 466 Chapter 20: Interpretive and Educational Programs 492 Chapter 21: Resource and Visitor Protection 526 Chapter 22: Relationships with the Military -

The Everglades Before Reclamation

Florida Historical Quarterly Volume 26 Number 1 Florida Historical Quarterly, Vol 26, Article 4 Issue 1 1947 The Everglades Before Reclamation J. E. Dovell Part of the American Studies Commons, and the United States History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/fhq University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Article is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Florida Historical Quarterly by an authorized editor of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation Dovell, J. E. (1947) "The Everglades Before Reclamation," Florida Historical Quarterly: Vol. 26 : No. 1 , Article 4. Available at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/fhq/vol26/iss1/4 Dovell: The Everglades Before Reclamation THE EVERGLADES BEFORE RECLAMATION by J. E. DOVELL Within our own generation a scientist who always weighed his words could say of the Everglades: Of the few as yet but very imperfectly explored regions in the United States, the largest perhaps is the southernmost part of Florida below the 26th degree of northern latitude. This is particularly true of the central and western portions of this region, which inland are an unmapped wilderness of everglades and cypress swamps, and off-shore a maze of low mangrove “keys” or islands, mostly unnamed and uncharted, with channels, “rivers” and “bays” about them which are known only to a few of the trappers and hunters who have lived a greater part of their life in that region. 1 This was Ales Hrdlicka of the Smithsonian Institution, the author of a definitive study of anthropology in Florida written about 1920 ; and it is not far from the truth today. -

SUMMER ADVENTURES Indigenous Origins O N T H E R O a D EVERGLADES NATIONAL PARK

SUMMER ADVENTURES Indigenous Origins O N T H E R O A D EVERGLADES NATIONAL PARK DID YOU KNOW? The Indigenous peoples of the Americas arrived from Asia more than 10,000 years ago. The prevailing theory is that they crossed from Siberia to what is now Alaska. Over the ensuing millennia, many of them migrated east and south, populating areas as distant as present-day Nevada and Brazil. Some of them formed communities in the Everglades. One of the major Indigenous peoples in the Everglades were the Calusa, who lived along the southwestern coast of the Florida Peninsula. They used shells to build earthwork platforms and barriers, potentially as protection from the ocean, and they subsisted largely on fish they caught from dugout canoes they crafted. The Calusa, together with the Tequesta and other Indigenous peoples, numbered about 20,000 when the Spanish landed in Florida in the early 16th century. By the late 18th century, their populations were dramatically smaller, decimated by diseases introduced by the Spanish to which they had no immunity. Around that time, Creeks from Georgia and northern Florida began migrating to South Florida, where they assumed the name “Seminoles.” In addition to hunting and fishing, the Seminole farmed corn, squash, melons, and other produce. Beginning in 1818, the U.S. waged a series of wars to remove the Seminoles from Florida. It managed to forcibly relocate some Seminoles to the Indian Territory, though others evaded capture by venturing into the Everglades. Today, Florida’s Seminole and Miccosukee tribes include thousands of members. Some live on reservations, while others live in off-reservation towns or cities. -

The English Invasion of Spanish Florida, 1700-1706

Florida Historical Quarterly Volume 41 Number 1 Florida Historical Quarterly, Vol 41, Article 7 Issue 1 1962 The English Invasion of Spanish Florida, 1700-1706 Charles W. Arnade Part of the American Studies Commons, and the United States History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/fhq University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Article is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Florida Historical Quarterly by an authorized editor of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation Arnade, Charles W. (1962) "The English Invasion of Spanish Florida, 1700-1706," Florida Historical Quarterly: Vol. 41 : No. 1 , Article 7. Available at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/fhq/vol41/iss1/7 Arnade: The English Invasion of Spanish Florida, 1700-1706 THE ENGLISH INVASION OF SPANISH FLORIDA, 1700-1706 by CHARLES W. ARNADE HOUGH FLORIDA had been discovered by Ponce de Leon in T 1513, not until 1565 did it become a Spanish province in fact. In that year Pedro Menendez de Aviles was able to establish a permanent capital which he called St. Augustine. Menendez and successive executives had plans to make St. Augustine a thriving metropolis ruling over a vast Spanish colony that might possibly be elevated to a viceroyalty. Nothing of this sort happened. By 1599 Florida was in desperate straits: Indians had rebelled and butchered the Franciscan missionaries, fire and flood had made life in St. Augustine miserable, English pirates of such fame as Drake had ransacked the town, local jealousies made life unpleasant. -

Cuban Experiences: 1959-1969 in Miami Pathfinder August, 2015

Cuban Experiences: 1959-1969 in Miami Pathfinder August, 2015 1. Key Books and Search Terms Search Terms Search su:Cuban American in the Library Catalog. The search will retrieve titles with subject headings containing “Cuban American” or Cuban Americans Specific subject searches: su:Cuban Americans History su:Cuban Florida su:Cuban Americans Biography Books Bretos, Miguel A. Cuba & Florida: Exploration of an Historic Connection, 1539-1991. Miami, Fla: Historical Association of Southern Florida (1991). Casavantes Bradford, Anita. The Revolution is for the Children: The Politics of Childhood in Havana and Miami, 1959-1962. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press (2014). García, María Cristina. Havana USA: Cuban Exiles and Cuban Americans in South Florida, 1959-1994. Berkeley: University of California Press (1996). Rieff, David. The Exile: Cuba in the Heart of Miami. New York: Simon & Schuster (1993). Shell-Weiss, Melanie. Coming to Miami: A Social History. Gainesville: University Press of Florida (2009). 2. Journal and Newspaper Articles Search the following databases, listed alphabetically in A-to-Z Databases, for articles: Academic Search Premier Access World News Latin America & the Caribbean (Gale World Scholar) Miami Herald New York Times (1851-2010) New York Times (1980-Current) ProQuest Central Search The Voice/La Voz newspapers of the Archdiocese of Miami (1961-1990). Available at St. Thomas University Library Media Archive, http://library.stu.edu/ulma/va/3005/. 3. Pertinent Historical Articles Badillo, David A. "Cuban Catholics in the United States, 1960-1980: Exile and Integration." The Americas 67, no. 1 (07, 2010): 118-119. Mandri, Flora M. González. "Operation Pedro Pan: A Tale of Trauma and Remembrance." Latino Studies 6, no. -

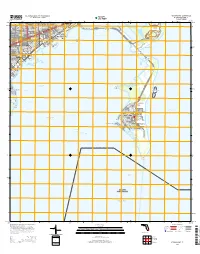

USGS 7.5-Minute Image Map for Key Biscayne, Florida

S W W KEY BISCAYNE QUADRANGLE U.S.2 DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR 7 T SW 31ST RD H H U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY FLORIDA-MIAMI-DADE CO. A V E 7.5-MINUTE SERIES 1ST TER SW 14THAVE 80°15' SW 2 972 12'30" 913 10' 80°07'30" 2ND ST ¬ «¬ SW576 2000mE 577 578 « 579 40 580 581 582 583 584 585 16 586 940 000 FEET 587 25°45' n█ 25°45' SW 22ND TER SW 29TH AVE E SW 23RD ST SW 21ST AVE V 9 S A «¬ W D 28 000m SW 34TH AVE SW 23RD TER R William M 48 N SW 23RD ST SW 25TH AVE 3 VE Lamar 2 SW 1ST AVE West Bay Heights 10 I A BRICKELL AVE Powell 28 SW 24TH ST 2 W SW 23RD AVE S M N IA Bridge Lake 48 D D SW 24TH TER M Bridge The S A SHORE DR W DR RIC Y V B TS KENBACKER CSW A H Pines E G 40 Bay Bridge SW 24TH TER Y EI SW 25TH ST H SW 25TH ST S n█ W W SHORE DR E 10 SW 25TH TER 1 16 7 SW 26TH ST n█ ¤£1 T 17 Virginia Key 15 H SW 26TH ST n█ 16 A SW 26TH LN V E 16SW 27TH ST E Intracoastal Waterway M MICANOPY AVE n█ A T T54S R41E H L MIAMI D TEQUESTA LN A R H LAMB J R S ARTHUR n█ OVERBROOK ST T 14 28 R n█ 47 E D Sister n█ OR 28 10 SH F Banks 47 AY A B I WASHINGTON ST S R Deering I S L Channel E E R SWANSON AVE S D T Grove R TRAPP AVE IC H K C E A LINCOLN AVE Isle N E n█ B B MATILDA ST A 510 000 Ocean View C INIA S K VIRG Virginia Beach W W E E20 SHIPPING AVE Heights AV R VIRGINIA ST 2 IL 22 C FEET MARY ST A 7 T S SW 32ND AVE W T R Y H H E Bear IG A T Bear V Cut E Cut Bridge 28 F 46 ¥^ OAK AVE 2846 n█ Dinner GRAND AVE GRAND AVE ▄PO 21 ¥^¥^ n Key 21 n█ █ Northwest Point CHARLES AVE FRANKLIN AVE Coconut 21 ROYAL RD Grove n█ n█ Dinner D V 28 L Key B 45 n█ 10 Channel 2845 N N P IN O O C D I N A A N R A A C VE 28 28 28 29 2844 MATHESON AVE 2844 Four-Way . -

A Short History of Florida

A Short History of MUSEUM OF FLORIDA HISTORY tiger, mastodon, giant armadillo, and camel) roamed the land. The Florida coastline along the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Mexico was very different 12,000 years ago. The sea level was A Short History much lower than it is today. As a result, the Florida peninsula was more than twice as large as it is now. The people who inhabited early Florida were hunters and gatherers and only occasionally sought big game. Their diets consisted mainly of Florida of small animals, plants, nuts, and shellfish. The first Floridians settled in areas where a steady water supply, good stone resources for Featured on front cover (left to right) tool-making, and firewood were available. • Juan Ponce de León, Spanish explorer, 1513 Over the centuries, these native people • Osceola, Seminole war leader, 1838 developed complex cultures. • David Levy Yulee, first U.S. senator from Florida, 1845 During the period prior to contact • Dr. Mary McLeod Bethune, founder of Bethune-Cookman with Europeans, native societies in the College in Daytona Beach, 1923 peninsula developed cultivated agriculture, trade with other groups in what is now the southeastern United States, and increased social organization, reflected in large temple mounds and village complexes. EUROPEAN EXPLORATION AND COLONIZATION Written records about life in Florida began with the arrival of the Spanish explorer and adventurer Juan Ponce de León in 1513. Florida Indian people preparing a feast, ca. 1565 Sometime between April 2 and April 8, Ponce de León waded ashore on the east coast of Florida, possibly near present- EARLY HUMAN day Melbourne Beach. -

The Legacy of Commodore David Porter, USN: Midshipman David Glasgow Farragut Part One of a Three-Part Series

The Legacy of Commodore David Porter, USN: Midshipman David Glasgow Farragut Part One of a three-part series Vice Admiral Jim Sagerholm, USN (Ret.), September 15, 2020 blueandgrayeducation.org David Glasgow Farragut | National Portrait Gallery In any discussion of naval leadership in the Civil War, two names dominate: David Glasgow Farragut and David Dixon Porter. Both were sons of David Porter, one of the U.S. Navy heroes in the War of 1812, Farragut having been adopted by Porter in 1808. Farragut’s father, George Farragut, a seasoned mariner from Spain, together with his Irish wife, Elizabeth, operated a ferry on the Holston River in eastern Tennessee. David Farragut was their second child, born in 1801. Two more children later, George moved the family to New Orleans where the Creole culture much better suited his Mediterranean temperament. Through the influence of his friend, Congressman William Claiborne, George Farragut was appointed a sailing master in the U.S. Navy, with orders to the naval station in New Orleans, effective March 2, 1807. George Farragut | National Museum of American David Porter | U.S. Naval Academy Museum History The elder Farragut traveled to New Orleans by horseback, but his wife and four children had to go by flatboat with the family belongings, a long and tortuous trip lasting several months. A year later, Mrs. Farragut died from yellow fever, leaving George with five young children to care for. The newly arrived station commanding officer, Commander David Porter, out of sympathy for Farragut, offered to adopt one of the children. The elder Farragut looked to the children to decide which would leave, and seven-year-old David, impressed by Porter’s uniform, volunteered to go. -

The Spanish in South Carolina: Unsettled Frontier

S.C. Department of Archives & History • Public Programs Document Packet No. 3 THE SPANISH IN SOUTH CAROLINA: UNSETTLED FRONTIER Route of the Spanish treasure fleets Spain, flushed with the reconquest of South Carolina. Effective occupation of its land from the Moors, quickly extended this region would buttress the claims its explorations outward fromthe Spain made on the territory because it had Carrribean Islands and soon dominated discovered and explored it. “Las Indias,” as the new territories were Ponce de Leon unsucessfully known. In over seventy years, their attempted colonization of the Florida explorers and military leaders, known as peninsula in 1521. Five years later, after the Conquistadores, had planted the cross he had sent a ship up the coast of “La of Christianity and raised the royal Florida,” as the land to the north was standard of Spain over an area that called, Vasquez de Ayllon, an official in extended from the present southern United Hispaniola, tried to explore and settle States all the way to Argentina. And, like South Carolina. Reports from that all Europeans who sailed west, the expedition tell us Ayllon and 500 Conquistadores searched for a passage to colonists settled on the coast of South the Orient with its legendary riches of Carolina in 1526 but a severe winter and gold, silver, and spices. attacks from hostile Indians forced them New lands demanded new regulations. to abandon their settlement one year later. Philip II directed In Spain, Queen Isabella laid down In 1528, Panfilo de Navarez set out the settlement policies that would endure for centuries. -

Frontiers of Contact: Bioarchaeology of Spanish Florida

P1: FMN/FZN/FTK/FJQ/LZX P2: FVK/FLF/FJQ/LZX QC: FTK Journal of World Prehistory [jowo] PP169-340413 June 4, 2001 16:36 Style file version Nov. 19th, 1999 Journal of World Prehistory, Vol. 15, No. 1, 2001 Frontiers of Contact: Bioarchaeology of Spanish Florida Clark Spencer Larsen,1,13 Mark C. Griffin,2 Dale L. Hutchinson,3 Vivian E. Noble,4 Lynette Norr,5 Robert F. Pastor,6 Christopher B. Ruff,7 Katherine F. Russell,8 Margaret J. Schoeninger,9 Michael Schultz,10 Scott W. Simpson,11 and Mark F. Teaford12 The arrival of Europeans in the New World had profound and long-lasting results for the native peoples. The record for the impact of this fundamental change in culture, society, and biology of Native Americans is well docu- mented historically. This paper reviews the biological impact of the arrival of Europeans on native populations via the study of pre- and postcontact skeletal remains in Spanish Florida, the region today represented by coastal Georgia and northern Florida. The postcontact skeletal series, mostly drawn 1Department of Anthropology, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio. 2Department of Anthropology, San Francisco State University, San Francisco, California. 3Department of Anthropology, East Carolina University, Greenville, North Carolina. 4Department of Cell and Molecular Biology, Northwestern University Medical School, Chicago, Illinois. 5Department of Anthropology, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida. 6Department of Archaeological Sciences, University of Bradford, Richmond Road, Bradford, West Yorkshire BD7 1DP, United Kingdom. 7Department of Cell Biology and Anatomy, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, 725 North Wolfe Street, Baltimore, Maryland. 8Department of Biology, University of Massachusetts—Dartmouth, North Dartmouth, Massachusetts. -

Download Catalogue

Dreams 1 of Unknown Islands Sasha Wortzel Sound installation, Cover: polymer PLA filament Big Cypress—Partnership 9.5 x 9.5 x 18 in. with Nature 2 3 7 min Year unknown Photo courtesy of Film still Pedro Wazzan Courtesy of the Everglades National Park Archives Kristan Kennedy Let us begin with “seashell resonance,” the folk more things, and therefore it’s been harder for me myth or phenomenon claiming that when you place to articulate specificity. I am thinking about different a conch shell against your ear, you can hear the binaries around gender and around time—around ocean. In actuality, the undulating and rushing sounds people, plants, and animals being labeled as invasive are generated by ambient noise passing through versus native—about queer ecology and queer the shell’s spiral body into our spiral ears, creating communities and histories.”4 We spent some time The Museum an occlusion effect. It is, in this moment, that the talking about Hito Steyerl’s writings and her use of imagined sounds of waves and the very real blood the term “free fall,” where the artist/author describes of All Possible flowing through our curving veins start to sing the mixed-up-ness one feels in times of disorientation 1 to each other. We feel connected, transported— or when there is a lack of an orienting horizon in the transmuted! We are the ocean.2 distance. Steyerl expands on the potential space of Shells In their solo exhibition Dreams of Unknown unknowing when she writes, “Traditional modes Islands, Sasha Wortzel proposes similar plangency of seeing and feeling are shattered.