Ffectiveness. the Second the Nation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2008-2009 Bill Witt

2008-2009 Title 1 Schools Required to Offer Supplemental Educational Services (SES) Title I schools that have not made Adequate Yearly Progress (AYP) for three or more consecutive years are required by the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001 (NCLB) to offer free tutoring to eligible students. District Name School Name Phase Academy for Business and Technology Academy for Business and Technology High 4 School Academy of Oak Park Academy of Oak Park - High School 5 Aisha Shule/WEB Dubois Prep. Academy Aisha Shule/WEB Dubois Prep. Academy 2 School School Benton Harbor Area Schools Hull Middle School 6 Buena Vista School District Buena Vista High School 4 Ricker Middle School 5 Casa Richard Academy Casa Richard Academy 4 Casman Alternative Academy Casman Alternative Academy 3 Center for Literacy and Creativity Center for Literacy and Creativity 2 Cesar Chavez Academy Cesar Chavez High School 2 Detroit Academy of Arts and Sciences Detroit Academy of Arts and Sciences High 2 School Detroit City School District Barbara Jordan Elementary 5 Barbour Magnet Middle School 8 Beckham, William Academy 6 Boykin Continuing Ed. Center 5 Boynton Elementary-Middle School 2 Central High School 5 Chadsey High School 5 Cleveland Middle School 8 Cody High School 5 Columbus Middle School 6 Communication and Media Arts HS 3 Cooley High School 5 Cooley North Wing 2 Courtis Elementary School 5 Crockett High School 4 Crosman Alternative High School 5 Denby High School 5 Detroit High School for Technology 2 Douglass Academy 4 Drew Middle School 8 Page 1 of 3 District -

New Look, Expansion Coming to Canton 6

Win a health} choppinl?os g spree! Win a healthy Loving care shopping spree at Buscb^with Peter At Angela Hospice, and f'Peter's volunteers provide ies ease respite from the waiting. Page C1 inside today's Observer ge C3. Your hometown newspaper serving Canton for 29 years Hope CANTON October is Breasl Cancer Awareness SUNDAY Month and new pro- October 5,2003 cedures give new 75 cents hope. Health, 06 VOLUME 29 NUMBER www.hometowhlife.com ©20Q3 HOMETOWN COMMUNICATIONS NETWORK I New look, expansion coming to Canton 6 BY JACK GLADDEN said Matt Johnson, marketing/training comforting seat cushions and molded Once the present building is redone, a STAFF WRITER manager for Goodrich Quality Theaters lumbar support backs. 5,400-square-foot addition will be con- of Grand Rapids which owns Canton 6. Stadium seating, which consists of structed on the back of the building that If the Canton 7 sounds like a radical "The first will be the remodeling of the concrete risers in every row of seats, will comprise the seventh auditorium. group from the 1960s, it's not. It's the existing building and the second will be allows patrons to have a heads-and- That will be a 312-seat state of the art new name of the Canton 6, the Ford the expansion." shoulders view above people in the row auditorium with a 50-foot wide screen. aise cash Road Theater which will be undergoing All six existing auditoriums will be in front of them. The project follows the announce- grSSgpSi an extensive remodeling and expansion refurbished and equipped with stadium Johnson said the theater will remain ment by Emagine Theaters that it is Tuesday, Oct. -

DETROIT BOARD of EDUCATION with Members of the Community Title VI Complaint Against Governor Rick Snyder

ABRIDGED VERSION DETROIT BOARD OF EDUCATION with Members of the Community Title VI Complaint Against Governor Rick Snyder July 27, 2015 1 2 3 4 Public education in America made this country great, but the racist tidal wave dissolving "Urban" schools in Michigan lead by Governor Snyder is the New Trail of Tears. Under this governor, urban schools have deteriorated into community eyesores and crime havens which are destroying the fabric of minority neighborhoods, and being replaced by experimental private models which have been proven ill equipped to provide quality learning environments. These institutions deny students with learning disabilities and other challenges an equal opportunity to an education, creating truly separate and unequal systems between white and black once again. Earl Rickman Past President, National Association of School Boards 5 TIMELINE The State of Michigan has been in authority over the Detroit Public Schools for approximately 13 of the last 16 years and is a recipient of Federal funds. Detroit Public Schools is a majority-minority district with the highest concentration of minorities of any city of 100,000 residents according to the 2010 US Census. 1994 In 1994, residents approved a $1.5 billion dollar capital bond program for Detroit Public Schools, which they will be paying for until at least 2033. The original bond was to be used to repair and renovate school buildings to service a then stable student enrollment of 167,000 students. The control of the spending of the bond dollars was a hotly contested issue, where various parties tried to take planning and spending authority from the school board. -

III. the Constitutional Violations (A) Constitutional Violations Found to Have Been Committed by the Detroit Board of Education

484 F.2d 215 (1973) Ronald BRADLEY et al., Plaintiffs-Appellees, v. William G. MILLIKEN, Governor of Michigan, etc.; Board of Education of the City of Detroit, Defendants-Appellants, and Detroit Federation of Teachers Local 231, American Federation of Teachers, AFL-CIO, Defendant-Intervenor-Appellee, and Allen Park Public Schools et al., Defendants-Intervenors-Appellants, and Kerry Green et al., Defendants-Intervenors-Appellees. Nos. 72-1809-72-1814. United States Court of Appeals, Sixth Circuit. June 12, 1973. Certiorari Granted November 19, 1973. 216*216 217*217 Frank J. Kelley, Atty. Gen., Robert A. Derengoski, Sol. Gen., Lansing, Mich., George T. Roumell, Jr., Louis D. Beer, Russ D. Boltz, William M. Saxton, Detroit, Mich., Robert J. Lord, Fair Haven, Mich., for appellants. Ralph B. Guy, Jr., U. S. Atty., David L. Norman, Asst. Atty. Gen., Dept. of Justice, Washington, D. C., for intervenor, United States. Richard P. Condit, Bloomfield Hills, Mich., for intervenor, Southfield Public Schools. Alexander B. Ritchie, Detroit, Mich., for intervenor, Denise Magdowski, and others. Theodore Sachs, Ronald R. Helveston, Detroit, Mich., for intervenor, Detroit Federation. William M. Saxton, John B. Weaver, Robert M. Vercruysse, X. Orhan, Detroit, Mich., for intervenor, Allen Park Public Schools. Douglas H. West, Robert B. Webster, Detroit, Mich., for intervenor, Grosse Pointe Public Schools. Kenneth B. McConnell, Bloomfield Hills, Mich., for intervenor, School District of City of Royal Oak. William T. Downs, Detroit, Mich., for Inter-Faith Centers for Racial Justice, Inc., amicus curiae. Theodore W. Swift, Foster, Lindemer, Swift & Collins, Lansing, Mich., Irwin Ellman Levin, Levin, Garvett, & Dill, Detroit, Mich., for intervenor, Michigan Education Assn. -

Annual Report

2016 – 2017 ANNUAL REPO RT 2016 –2017 Annual Report Mission Statement Wayne County Community College District’s mission is to empower individuals, businesses and communities to achieve their goals through excellent and accessible services, culturally diverse experiences and globally competitive higher education and career advancement programs. One Vision, One District, One College WCCCD: • Serves 32 communities encompassing approximately 500 square miles with nearly 1.8 million people throughout Wayne County, one of the largest counties in the State of Michigan. • Has five campus locations and the Mary Ellen Stempfle University Center. • Offers more than 120 certificate and degree programs. As a publicly funded institution, the Wayne County Community College District is committed to providing our community information pertaining to the operations of the District. As part of our transparency efforts, the Wayne County Community College District complies with Sec. 209 in P.A. 201 of 2012, the education omnibus budget bill, which requires community colleges to publish transparency webpage and stipulate the content. 1 2016 –2017 Annual Report ATHLETICS “My goal through sports is to challenge the student athlete to surpass his or her own expectation whether on or off the court, not only as a good athlete but a better person in the game of life.” - Rogeric Turner, Athletic Director Rogeric Turner Athletic Director WCCCD is part of the Michigan Community College Athletic Association (MCCAA) – Eastern Conference. We are also a member of the National Junior College Athletic Association (NJCAA) – Region XII. The following sports are offered at WCCCD: Women’s cross country, basketball and bowling. Men’s cross country, basketball, bowling and golf. -

Guide to the Detroit Commission on Community Relations (DCCR) / Human Rights Department Records

Guide to the Detroit Commission on Community Relations (DCCR) / Human Rights Department Records This finding aid was created using ArchivesSpace on July 24, 2019 English Describing Archives: A Content Standard Walter P. Reuther Library 5401 Cass Avenue Detroit, MI 48202 URL: https://reuther.wayne.edu Guide to the Detroit Commission on Community Relations (DCCR) / Human Rights Department Records This finding aid was created using ArchivesSpace on July 24, 2019 English Describing Archives: A Content Standard Walter P. Reuther Library 5401 Cass Avenue Detroit, MI 48202 URL: https://reuther.wayne.edu Guide to the Detroit Commission on Community Relations / Human Rights Department Records UR000267 Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 History ............................................................................................................................................................ 4 Scope and Content ......................................................................................................................................... 4 Arrangement ................................................................................................................................................... 6 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 6 Related Materials .......................................................................................................................................... -

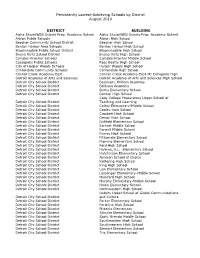

Persistently Lowest-Achieving Schools by District August 2010

Persistently Lowest-Achieving Schools by District August 2010 DISTRICT BUILDING Aisha Shule/WEB Dubois Prep. Academy School Aisha Shule/WEB Dubois Prep. Academy School Albion Public Schools Albion High School Beecher Community School District Beecher High School Benton Harbor Area Schools Benton Harbor High School Bloomingdale Public School District Bloomingdale High School Buena Vista School District Buena Vista High School Camden-Frontier Schools Camden-Frontier Middle School Cassopolis Public Schools Ross Beatty High School City of Harper Woods Schools Harper Woods High School Clintondale Community Schools Clintondale High School Conner Creek Academy East Conner Creek Academy East-MI Collegiate High Detroit Academy of Arts and Sciences Detroit Academy of Arts and Sciences High School Detroit City School District Beckham, William Academy Detroit City School District Bethune Academy Detroit City School District Burns Elementary School Detroit City School District Central High School Cody College Preparatory Upper School of Detroit City School District Teaching and Learning Detroit City School District Coffey Elementary/Middle School Detroit City School District Cooley High School Detroit City School District Crockett High School Detroit City School District Denby High School Detroit City School District Duffield Elementary School Detroit City School District Earhart Middle School Detroit City School District Farwell Middle School Detroit City School District Finney High School Detroit City School District Fitzgerald Elementary School -

![]|!Pg* Hours I I Common of Ing Your Own Slip Covers and Draperies.” the Instructions Big Wardrobe 22 * Council I - It](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6801/pg-hours-i-i-common-of-ing-your-own-slip-covers-and-draperies-the-instructions-big-wardrobe-22-council-i-it-3356801.webp)

]|!Pg* Hours I I Common of Ing Your Own Slip Covers and Draperies.” the Instructions Big Wardrobe 22 * Council I - It

Wednesday, March IS, 1942 DETROIT EVENING Tl Mt, S (PHOXE CHEERY S 800) PAGE 5 Where City's Defenses LIBERTY LIMERICKS Major Pritchard STORE HOURS: DAILY, 9:30 to 5:30; SATURDAY, 9:30 to 6:00 . TELEPHONE CHerry 5100 Win Praise of Back at Custer You ( an Freud, Defroii needs air raid wardens. It’s HUDSON’S Col. B. B. As Post Provost Here is a list of the schools where services Tlm*l Sl»lt ( nrrr*|M>ndrnl you may volunteer your for P:3O p. m. By IIOROTHV WILLIAMS FORT Ct’STER. March IS between 10 a. m. and Headquarters. rift between state of Civilian Defense Whatever the Maj. Ftank Pritchard Lansing, Barium Hotel. jnd city authority ti officials over former provost marshal at Fort Miller High School. 2522 Dubois pro- Color defense a’ Chairs with in s Custer, Boudoir Detroit civilian today was bark his old *t Gay reet gram, this still is regarded as a desk again after completing a Southwestern High School. 6921 together % * three tour of duty at the metropolitan area bound T « months West Fort street. by its common problems a« a nat- hattalion staff officer* school, Fort Post Srhool, 8200 Midland ave- . V You Can Choose from 3 0 Attractive Styles Benning. (la. ural target, in the opinion of Col. nue. ' During his absence Lieut. Rich- * III High School, >-* B B Freud. E. ha* been the post * Northern 9026 i Want to brighten up the sunroom, bedroom or living deputy of ard Barrett **. \ The colonel, director There was a young farmer provost marshal Woodw ai d avenue. -

High School Registration Summary

High School Registration Summary Participating in the Michigan e-Transcript Initiative will help ensure that schools may retain their federal stimulus dollars under the America Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009. During e-Transcript registration, a school staff member selected one of four phases to complete the installation, testing and training steps. The phases are depicted below: Installation Phases Phase Start End 1 December 1, 2009 February 28, 2010 2 March 1, 2010 May 31, 2010 3 June 1, 2010 August 31, 2010 4 September 1, 2010 November 30, 2010 When viewing this registration summary, you will notice that schools fall into one of nine statuses: Status Definition Installing The school received the installation instructions, is currently installing the software and sending test transcripts. Troubleshooting Docufide and/or the school are working on an issue regarding the student information system. Non-compliant The school sent the test transcripts, but is missing the student Unique Identification Code, building code and/or district code, labeled (format) as UIC, BCODE and DCODE, respectively. The school has been notified of these missing fields and Docufide is awaiting new test files to be sent. Non-compliant The school has not completed registration by the December 31, 2009 deadline or has not become "live" with the service in the selected phase. Pending training The school has completed the software installation and the transcripts contain the three required fields. The staff members at the school who will process transcripts still need to attend the online training. Unresponsive The school has received the installation instructions, but did not install the software and/or send test transcripts. -

Detroit, Michigan

Detroit Table of Contents Foreword ......................................................................................................................................... 2 Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 3 Detroit in Books, Serials, and Maps ............................................................................................... 5 Books and Serials ........................................................................................................................ 5 Primary Sources ...................................................................................................................... 5 Secondary Sources .................................................................................................................. 6 Detroit in Maps ........................................................................................................................... 7 Early Maps .............................................................................................................................. 7 Physical Features .................................................................................................................... 7 Cultural Features ..................................................................................................................... 8 Early Documents (Before 1850) ................................................................................................... 10 -

Reforming and Improving the Detroit Public Schools, Council

Reforming and Improving the Detroit Public Schools: Report of the Strategic Support Teams of the Council of the Great City Schools Submitted to the Detroit Public Schools By the Council of the Great City Schools 2008 Reforming and Improving the Detroit Public Schools ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The Council of the Great City Schools thanks the many individuals who contributed to this project to reform and improve the Detroit Public Schools. Their efforts and commitment were critical to our ability to present the district with the best possible proposals. First, we thank General Superintendent of Schools Dr. Connie Calloway. It is not easy to ask for the kind of review that a project such as this entails. It takes leadership, courage, openness, and an uncompromising commitment to the city’s children. She has those qualities in abundance. Second, we thank the Board of Education of the Detroit Public Schools for supporting this effort and meeting with our teams to discuss issues and challenges facing the district. We hope this report proves useful as the board leads the district through this critical period. Third, we thank staff members and teachers in the Detroit Public Schools, who provided all the time, documents, and data that the Council team needed to do its work. Their openness was critical to our understanding of the challenges faced by the Detroit school system. Fourth, we thank the many individuals, groups, organizations, and associations with which we met. Our only regret is that we were unable to meet with everyone who we know had something valuable to contribute. Fifth, the Council thanks the school districts and organizations that contributed staff to this effort. -

Michigan Department of Community Health Mercury-Free Schools in Michigan

Michigan Department of Community Health Mercury-Free Schools in Michigan Entity Name City Eastside Middle School Bay City Trinity Lutheran School St. Joseph A.D. Johnston Jr/Sr High School Bessemer Abbot School Ann Arbor Abbott Middle School West Bloomfield Academic Transitional Academy Port Huron Academy for Business and Technology Elementary Dearborn Ada Christian School Ada Ada Vista Elementary Ada Adams Christian School Wyoming Adams Elementary School Bad Axe Adams Middle School Westland Adlai Stevenson Middle School Westland Adrian High School Adrian Adrian Middle School 5/6 Building Adrian Adrian Middle School 7/8 Building Adrian Airport Senior High School Carleton Akiva Hebrew Day School Southfield Akron-Fairgrove Elem. School Akron Akron-Fairgrove Jr/Sr High School Fairgrove Alaiedon Elementary School Mason Alamo Elementary School Kalamazoo Albee Elementary School Burt Albert Schweitzer Elementary School Westland Alcona Elementary School Lincoln Alcona Middle School Lincoln Alexander Elementary School Adrian Alexander Hamilton Elementary School Westland All Saints Catholic School Alpena Allegan High School Allegan Allegan Street Elementary School Otsego Allen Elementary School Southgate Allendale Christian School Allendale Allendale High School Allendale Allendale Middle School Allendale Alma Middle School Alma Alma Senior High School Alma Almont Middle School Almont Alpena High School Alpena Alward Elementary School Hudsonville Amberly Elementary School Portage Amerman Elementary School Northville Anchor Bay High School Fair Haven Anchor Bay Middle School North New Baltimore Anderson Elementary School Bronson Anderson Middle School Berkley Andrew G. Schmidt Middle School Fenton Andrews Elementary School Three Rivers Angell School Ann Arbor Angelou, Maya Elementary School Detroit Angling Road Elementary School Portage Angus Elementary School Sterling Heights Ann Arbor Open at Mack School Ann Arbor Ann J.