The Role of Management in Hospitality

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Job Title: Hotel Manager Department: Hotel Reports To: General Manager Supervises: Front Desk, Housekeeping, Guest Services Grade: 14

Job Description Job Title: Hotel Manager Department: Hotel Reports to: General Manager Supervises: Front Desk, Housekeeping, Guest Services Grade: 14 Summary of Position: This position manages the day-to-day operations of the Front Desk, Housekeeping, and Guest Services. The Hotel Manager creates and implements policies and procedures that will establish Land’s End Resort as Alaska’s premier destination resort hotel. This position is primarily responsible for management of Hotel and Lodge room inventory; for maximizing hotel occupancy and profit through rate optimization, support and communicate sales and marketing efforts to staff, and quality guest service. The position has managerial authority and decision making discretion with respect to purchasing; hiring and firing; training and reviewing staff performance; and creating performance goals and incentives. The Hotel Manager will develop quarterly departmental goals, with the GM, and will guide the staff to ensure action plans are implemented to achieve them. The Hotel Manager must set the example for staff to deliver a standard of service and presentation that meets guests' needs and expectations. Essential Functions: 1. Primarily accountable for administration of hotel operations and the implementation of service standards in order to maximize guest and employee satisfaction in accordance with LEAC guidelines. 2. Directly responsible for rate and room inventory management across all hotel systems (RoomKey, Genares/Synexis, Expedia etc.) 3. Direct hotel staff in enforcing and maintaining existing LEAC procedures to ensure operational compliance. 4. Perform the responsibility of all hotel job descriptions if required. 5. Review weekly schedules for conformity to approved labor budgets. 6. Perform daily and weekly review of timesheets for overtime control and conformity to schedule. -

Restaurant General Manager Job Duties

Restaurant General Manager Responsibilities: Delivers revenues and profits by developing, marketing, financing, and providing appealing restaurant service; managing staff. Restaurant General Manager Job Duties: Establishes restaurant business plan by surveying restaurant demand; conferring with people in the community; identifying and evaluating competitors; preparing financial, marketing, and sales projections, analyses, and estimates. Attracts customers by developing and implementing marketing, advertising, public and community relations programs; evaluating program results; identifying and tracking changing demands. Maintains operations by implementing policies and standard operating procedures; implementing production, productivity, quality, and customer service standards; determining and implementing system improvements. Maintains customer satisfaction by monitoring, evaluating, and auditing food, beverage, and service offerings; initiating improvements; building relationships with preferred patrons. Accomplishes restaurant objectives by recruiting, selecting, orienting, training, assigning, scheduling, coaching, counseling, and disciplining management staff; communicating job expectations; planning, monitoring, appraising, and reviewing job contributions; planning and reviewing compensation actions; enforcing policies and procedures. Knowledge of budgets, inventory’s and cost controls for FOH and BOH Maintains safe, secure, and healthy facility environment by establishing, following, and enforcing sanitation standards and -

Country General Manager in Cpg Multinationals

the changing role of the Country General Manager in cpg multinationals THE CHANGING ROLE OF THE COUNTRY GENERAL MANAGER in CPG multinationals abOUT sPENCER sTUART Spencer Stuart is one of the world’s leading executive search consulting firms. Privately held since 1956, Spencer Stuart applies its extensive knowledge of industries, functions and talent to advise select clients — ranging from major multinationals to emerging companies to nonprofit organisations — and address their leadership requirements. Through 52 offices in 27 countries and a broad range of practice groups, Spencer Stuart consultants focus on senior-level executive search, board director appointments, succession planning and in-depth senior executive management assessments. For more information on Spencer Stuart, please visit www.spencerstuart.com. THE CHANGING ROLE OF THE COUNTRY GENERAL MANAGER in CPG multinationals Over a six-month period, Spencer Stuart consultants interviewed over 30 executives at major multinationals in the consumer packaged goods sector about the role of the country general manager. The interviewees comprised current general managers, CEOs, regional presidents and category heads as well as other senior executives. We wished to explore the effect of developments in the CPG world on the role of the country general manager. These developments include the increasing globalisation of functions, new category structures, country clustering, shared service centres, the emergence of global retailers and the need for the development of national talent. Major CPG multinationals have been seeking to optimise their scale and the impact of their brands globally since at least the mid-1980s. So while some of these developments may not be inherently new, it is more their convergence and acceleration that has had an impact on the general manager’s role recently. -

General Manager's Authority, Duties

GENERAL MANAGER’S AUTHORITY, DUTIES & RESPONSIBILITIES The General Manager is hired by and reports directly to the Cooperative’s Board of Directors. The General Manager is responsible and accountable for all the following areas: Board Relations: • Work with the Board President to set Board meeting agendas. • Ensure Board packets are prepared and distributed in advance of Board meetings. • Prepare for and attend Board meetings. • Prepare and present timely and effective reports to the Board supported with appropriate analysis; reports will focus on: – Monitoring business performance and compliance with Board policies and limits defined by the Board. – Progress towards goals. – Significant deviations from goals, compliance or sound business performance. – Plans for corrective action. • Maintain effective communication and working relationships with Board Directors and Board President. Finance: • Oversee preparation of annual operating and capital budgets for final approval by the Board of Directors. • Oversee preparation and analysis of quarterly financial statements for presentation to the Board of Directors. • Ensure budgeted financial targets are met; provide rationale /explanation for deviations. • Ensure the financial viability of the Co-op. Operations: • Determine product and pricing strategies. • Control labor costs and enhance productivity. • Ensure timely negotiations and renewals of any lease and/or sublease. • Ensure the physical plant is adequately maintained and meets all security, health and safety standards. • Ensure efficient operational systems; identify and solve operational problems. • Plan for and implement changes and improvements to physical operation. • Ensure assets are utilized productively and safeguarded from loss. Human Resources: • Establish and ensure adherence to personnel policies. • Recruit, orient, evaluate, discipline, supervise and guide management staff. • In collaboration with the Human Resources manager, assist department heads with HR needs within their departments. -

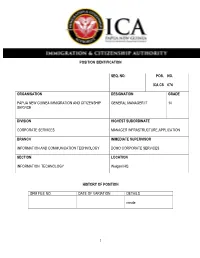

1 Position Identification Seq. No. Pos. Ica Cs No. 074

POSITION IDENTIFICATION SEQ. NO. POS. NO. ICA CS 074 ORGANISATION DESIGNATION GRADE PAPUA NEW GUINEA IMMIGRATION AND CITIZENSHIP GENERAL MANAGER IT 14 SERVICE DIVISION HIGHEST SUBORDINATE CORPORATE SERVICES MANAGER INFRASTRUCTURE,APPLICATION BRANCH IMMEDIATE SUPERVISOR INFORMATION AND COMMUNICATION TECHNOLOGY DCMO CORPORATE SERVICES SECTION LOCATION INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY Waigani HQ HISTORY OF POSITION DPM FILE NO. DATE OF VARIATION DETAILS create 1 1 PURPOSE OF POSITION The General Manager IT manages the procurement and provision of agency IT services, advises senior management on strategic IT issues, manages business continuity, and supervises the IT Section. 2 DIMENSIONS The General Manager IT leads a team of 12 officers The IT budget is estimated at around K1m but is expected to grow significantly due to organizational expansion both in PNG and at overseas missions. Systems supporting and repairing include: INFRASTRUCTURE: Microsoft Servers; File and print, Terminal Server, Remote Desktop Server, BMS (SQL Server) Networking equipment: Net gear wireless routers and CISCO routers/switches Desktop computers and laptops operating Windows XP and Windows 7 Printer configuration and fault finding. UPS installation and configuration. Anti Virus system. Active Directory – new User accounts and password resets. Acronis and external Hard drives for backup. Security Card system Phone cabling and network patching. APPLICATION SYSTEMS: PNG Border Management System (BMS) TARDIS (Passport System) Gmail (email and groupware) Website (currently Joomla! CMS) Standard Desktop environment (e.g. MS Office) 3 NATURE/SCOPE The General Manager IT is a Branch Head within the Corporate Services Division, the other branches being Finance and Administration and Human Resources. The position leads and manages a team of 12 staff in the provision of IT services including level 2 & 3 support and maintenance for Applications and Infrastructure systems, help desk services, and the conduct of IT related development project work. -

ASSISTANT RECEPTION MANAGER Location: Reception Reports Into: Front of House Manager, General Manager Persons Supervised: Receptionists and Reception Team Leader

Job Title: ASSISTANT RECEPTION MANAGER Location: Reception Reports into: Front of House Manager, General Manager Persons Supervised: Receptionists and Reception Team Leader Main Objective: To manage the operations of the Front Office department to the standards set out by the hotel and company. To assume overall responsibility for the co-ordination and overseeing of the hotel operations in the absence of the Front of House Manager. To ensure the safety and security of the guests. Key Relationships: To maintain all inter-departmental relationships to ensure seamless customer service throughout the hotel. Main Duties: • To oversee the front desk ensuring we achieve total guest satisfaction • To ensure that the Front Office team are wearing correct uniform in line with company standards and their name badges. • Have a thorough knowledge of all systems and procedures used with in Front Office so that you are able to give decisive direction and supervising to the team • To welcome guests to the hotel in a courteous and helpful manner • To ensure that a suitable method of payment for each guest account at the time of check in • Understand the credit procedures and be able to explain them to guests where applicable • Ensure that all guests receive an efficient and correct check in and that all procedures are followed • Ensure that all guest profiles are updated and present, including for all international visitors their passport details (if not UK or Irish residents) • To comply with hotel policy regarding floats and access to the safe • To -

Annual Report 2019

EUROPEAN TRAVEL COMMISSION ANNUAL REPORT 2019 CONTENTS CONTENTS CONTENTS 04-05 President’s Foreword 06 Executive Director’s Message Rue du Marché aux Herbes 61 07 1000 Brussels, Belgium ETC Executive Unit www.etc-corporate.org 08-09 [email protected] Tourism Trends European Travel Commission @ETC_Corporate 10 Market Intelligence Group 11-15 Research Activities 16-18 Marketing Activities 19 Marketing Group 20-21 Partnerships 22-23 Corporate Communications 24-25 Membership 26-28 Advocacy Disclaimer: Whilst every care has been 29 taken in the compilation of this publica- Funding tion and the information and statements 30 contained in it are believed to be correct at the time of going to press, the publi- Who was Who at ETC shers and promoters of this publication 31 are not liable for any inaccuracies. ETC Members 2 • ANNUAL REPORT 2019 • EUROPEAN TRAVEL COMMISSION EUROPEAN TRAVEL COMMISSION • ANNUAL REPORT 2019 • 3 PRESIDENT’S FOREWORD PRESIDENT’S FOREWORD PRESIDENT’S FOREWORD Dear friends and partners of ETC, ur world has been hit mid-ship by an unexpected threat which makes us pause and reflect. We are facing an unprecedented menace to our societies and livelihoods, Ocalled “Coronavirus”. This pandemic knows neither borders nor nationality. All sectors of the economy are affected, but the challenges we are facing in our tourism ecosystem are remarkable. Our SMEs, family businesses, traders, travel agencies, but also our larger players such as airlines, tour operators and cruise lines are dealing with an attack on our industry that has no parallel in recent history. The tourism ecosystem in Europe is a key driver for employment and economic development: • Europe accounts for 50% of the world tourism market in terms of arrivals; • It contributes to 10% of the EU’s GDP; • It accounts for over 11% of employment in the EU, i.e. -

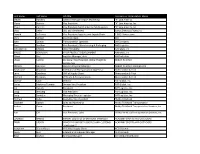

First Name Last Name Job Title Company Or Organization Name

First name Last name Job title Company or Organization Name Steven Hawkins General Manager Import Marketing "K" Line America Maria Bodnar Vice President "K" Line America, Inc. Shaun Gannon Vice President North America Field Logistics "K" Line America, Inc. Chas Deller CEO and CHAIRMAN 10XOCEANSOLUTIONS,INC Donald La France Vice President Logistics and Supply Chain 1-800-Flowers.com Chris McNeil Sourcing Agent 3M John Ladwig Transportation Specialist 3M Company Russ Boullion Vice President - Warehousing & Packaging A&R Logistics XIANGMING CHENG CEO/ PRESIDENT AAmetals, Inc BRUCE FERGUSON VP OF PRODUCT DEVELOPMENT AAmetals, Inc Eileen Wei Logistics Manager, Asia AB Electrolux Ulises Carrillo Divisional Vice President, Global Freight & Abbott Nutrition Distribution William Gaiennie Logistics Program Manager Abbott Nutrition International Sarah Jane Chapman International Transportation Supervisor Abercrombie & Fitch Larry Grischow GVP of Supply Chain Abercrombie & Fitch Michael Sherman VP Trade & Transportation Abercrombie & Fitch Gunnar Gose Director ABF Global, Inc. Carlos Martinez-Tomatis Division Vice President ABF Global, Inc. Jim Ingram President ABF Logistics, Inc. Doug Riesberg Vice President ABF Logistics, Inc. Craig Sandefur Managing Director Logistics ABF Logistics, Inc. Michael Kelso Executive Vice President Ability Tri-Modal Elizabeth Gaston Sales and Marketing Ability Tri-Modal Transportation Joshua Owen President Ability Tri-Modal Transportation Services, Inc. Ron Gill Vice President, Sales Ability/Tri-Modal Transportation Services, -

CM-051 Annual Report 0422.Indd

COSTA MESA CONFERENCE AND VISITOR BUREAU TM 575 Anton Blvd., Suite 880 Costa Mesa, CA 92626 ANNUAL REPORT FISCAL YEAR ENDING JUNE 2015 TM 2 FISCAL OVERVIEW COSTA MESA CVB ANNUAL REPORT 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS President’s Message from Costa Mesa Conference and Visitor Bureau 5 Fiscal Overview 9 BIA 10 The Impact of Tourism 14 Travel News Update/ U.S. Travel News 18 Trends in Travel 20 Domestic Travel 21 International Travel 23 Partnerships 31 Marketing Overview 35 Marketing Overview: Fiscal Year 2014/2015 36 New Branding 37 TravelCostaMesa.com 39 Social Media 53 Travel Costa Mesa Blog 56 Costa Mesa Email Newsletter 57 Travel Costa Mesa Calendar 58 Paid Media 59 Print Campaign 59 Stay and Get $50 Campaign 60 Valentine’s Day Weekend Getaway Campaign 61 Costa Mesa Restaurant Week 62 TripAdvisor Sponsorship Page & Banner Ads 63 Public Relations 64 International Efforts 65 COSTA MESA CVB ANNUAL REPORT 3 CITY OF THE ARTS™ Surrounded by a richness in culture, shopping and 2013 generated $4.3 billion in state taxes and directly dining, proximity to the Pacifi c Ocean and near supported 965,800 jobs. perfect year-round climate, the City of the Arts™ is in an advantageous position to attract both domestic Hotel renovations and fantastic new dining options will and international guests when traveling to Orange continue to impress overnight guests visiting Costa County. The Costa Mesa Conference and Visitor Mesa. Product improvements include the Ayres Hotel Bureau (Bureau) aggressively markets the city as a & Suites’ inspiring new lobby and business center. The desirable, overnight leisure destination focusing on Marriott guest will experience a refreshed, modern feel the experiences of shopping, the arts and dining. -

General Manager Job Description Company Overview

General Manager Job Description Company Overview: Oldham Goodwin Group, LLC is headquartered in Bryan/College Station, Texas. It has approximately 360 employees and serves real estate owners, investors and occupiers through Central Texas offices. Oldham Goodwin offers advisory services and execution for property sales and leasing, property and project management, valuation, development services, investment management, and research and consulting. Oldham Goodwin executes strategic, integrated and comprehensive commercial real estate brokerage services for tenants/occupiers, property owner and focused vertical industries in the office, industrial, retail, multifamily, and hospitality sectors. Position Overview: The NEW Best Western PLUS is looking for an experienced Hotel General Manager. This position is accountable for the overall success of the hotel, meeting and exceeding revenue measures and ensuring guest satisfaction. The General Manager must supervise all areas of the hotel while maintaining brand standards and needs to achieve superior levels of quality for all clients. Primary Responsibilities and Duties Demonstrate a positive, professional, and client-oriented attitude about the company with coworkers, tenants, clients, and the public whether contact is by mail, telephone, or in person. Constantly strive for improvements in work process and results to better meet client's expectations. On assigned properties, act as Oldham Goodwin Group’s primary coordinator to assure that our efforts fully meet and exceed contractual property management obligations. Direct the day-to-day activities of loss prevention, risk management, safety/security, maintenance, sales, marketing, and other operations. Develop operating income/expense budgets and capital budgets which reflect the owner's objectives for operating the property, cash flow requirements and leasing strategy. -

Press Release

PRESS RELEASE FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: March 12, 2019 Contact: Vice President, Ashley Whittaker Company: Sports Facilities Management Email: [email protected] Sports Facilities Management (SFM) Promotes Award- Winning General Manager To National Leadership Team General Manager of Rocky Top Sports World, Lori Moore, Promoted to Account Executive of the Industry Leading Professional Facility Management Firm (Clearwater, FL) March 12, 2019: The Sports Facilities Management (SFM), the chosen operator for many of the nation’s premier sports tourism facilities, has promoted Rocky Top Sports World General Manager, Lori Moore to National Account Executive. Moore has been an influential leader in the SFM roster and the new position will allow her to assist communities around the country in achieving the same success produced at Rocky Top Sports World. In her new role, Moore will oversee facilities currently in the SFM National Network, onboard new facilities in the firm’s growing portfolio, and continue to provide leadership for Rocky Top Sports World. Gatlinburg City Manager Cindy Cameron Ogle congratulated Moore and remarked “We are very pleased that Lori is able to take advantage of this professional opportunity while continuing to be based in Sevier County and remaining heavily involved with Rocky Top Sports World.” She will also lead the firm’s ‘Access Program’ with the mission of improving access to youth sports opportunities for all – regardless of socio-economic status. As the firm manages Moore’s transition, a nation-wide search is underway to replace her for Rocky Top’s General Manager position. “Our complex continues to reach new heights in sports tourism and that success is a direct result of Lori’s leadership and the efforts of our team” said Sevier County Mayor Larry Waters. -

Deputy General Manager - Administrative Services

Job Description Please note this job description is not designed to cover or contain a comprehensive listing of activities, duties or responsibilities that are required of the employee for this job. Job title Deputy General Manager - Administrative Services GENERAL PURPOSE Under policy direction from the General Manager, plans, organizes, integrates, directs, manages, and evaluates the activities, operations, and services of the Administrative Services Branch and its departments, or other departments as assigned; directs and manages the development of short- and long-term goals and objectives consistent with the Strategic Plan and annual business plan and ensures their effective execution; ensures all assigned operations and functions serve the needs of customers/rate payers throughout the District’s service area, while complying with applicable laws and regulations; and performs related duties as assigned. DISTINGUISHING CHARACTERISTICS This executive classification oversees and directs all activities of the Administrative Services Branch and its departments including short- and long-term planning and the development and administration of branch/departmental policies, procedures, and services. This class provides highly complex assistance to the General Manager in a variety of administrative, coordinative, analytical, and liaison capacities. Successful performance of the work requires knowledge of public policy, District functions and activities, including the role of the District’s Board of Directors. Responsibilities include coordinating the activities of the branch/department with those of other departments and outside agencies and managing and overseeing the complex and varied functions of the branch. The incumbent is accountable for accomplishing branch planning and operational goals and objectives, and for furthering District goals and objectives within general policy guidelines.