A Manual for Growing and Using Seed from Herbaceous Plants Native To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phylogeny of Elymus Ststhh Allotetraploids Based on Three Nuclear Genes

Reticulate Evolutionary History of a Complex Group of Grasses: Phylogeny of Elymus StStHH Allotetraploids Based on Three Nuclear Genes Roberta J. Mason-Gamer*, Melissa M. Burns¤a, Marianna Naum¤b Department of Biological Sciences, The University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, Illinois, United States of America Abstract Background: Elymus (Poaceae) is a large genus of polyploid species in the wheat tribe Triticeae. It is polyphyletic, exhibiting many distinct allopolyploid genome combinations, and its history might be further complicated by introgression and lineage sorting. We focus on a subset of Elymus species with a tetraploid genome complement derived from Pseudoroegneria (genome St) and Hordeum (H). We confirm the species’ allopolyploidy, identify possible genome donors, and pinpoint instances of apparent introgression or incomplete lineage sorting. Methodology/Principal Findings: We sequenced portions of three unlinked nuclear genes—phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase, b-amylase, and granule-bound starch synthase I—from 27 individuals, representing 14 Eurasian and North American StStHH Elymus species. Elymus sequences were combined with existing data from monogenomic representatives of the tribe, and gene trees were estimated separately for each data set using maximum likelihood. Trees were examined for evidence of allopolyploidy and additional reticulate patterns. All trees confirm the StStHH genome configuration of the Elymus species. They suggest that the StStHH group originated in North America, and do not support separate North American and European origins. Our results point to North American Pseudoroegneria and Hordeum species as potential genome donors to Elymus. Diploid P. spicata is a prospective St-genome donor, though conflict among trees involving P. spicata and the Eurasian P. -

Literature Cited Robert W. Kiger, Editor This Is a Consolidated List Of

RWKiger 26 Jul 18 Literature Cited Robert W. Kiger, Editor This is a consolidated list of all works cited in volumes 24 and 25. In citations of articles, the titles of serials are rendered in the forms recommended in G. D. R. Bridson and E. R. Smith (1991). When those forms are abbreviated, as most are, cross references to the corresponding full serial titles are interpolated here alphabetically by abbreviated form. Two or more works published in the same year by the same author or group of coauthors will be distinguished uniquely and consistently throughout all volumes of Flora of North America by lower-case letters (b, c, d, ...) suffixed to the date for the second and subsequent works in the set. The suffixes are assigned in order of editorial encounter and do not reflect chronological sequence of publication. The first work by any particular author or group from any given year carries the implicit date suffix "a"; thus, the sequence of explicit suffixes begins with "b". Works missing from any suffixed sequence here are ones cited elsewhere in the Flora that are not pertinent in these volumes. Aares, E., M. Nurminiemi, and C. Brochmann. 2000. Incongruent phylogeographies in spite of similar morphology, ecology, and distribution: Phippsia algida and P. concinna (Poaceae) in the North Atlantic region. Pl. Syst. Evol. 220: 241–261. Abh. Senckenberg. Naturf. Ges. = Abhandlungen herausgegeben von der Senckenbergischen naturforschenden Gesellschaft. Acta Biol. Cracov., Ser. Bot. = Acta Biologica Cracoviensia. Series Botanica. Acta Horti Bot. Prag. = Acta Horti Botanici Pragensis. Acta Phytotax. Geobot. = Acta Phytotaxonomica et Geobotanica. [Shokubutsu Bunrui Chiri.] Acta Phytotax. -

Soil Heterogeneity and the Distribution of Native Grasses in California: Can Soil Properties Inform Restoration Plans? 1, KRISTINA M

Soil heterogeneity and the distribution of native grasses in California: Can soil properties inform restoration plans? 1, KRISTINA M. HUFFORD, SUSAN J. MAZER, AND JOSHUA P. S CHIMEL Ecology, Evolution and Marine Biology, University of California, Santa Barbara, California 93106 USA Citation: Hufford, K. M., S. J. Mazer, and J. P. Schimel. 2014. Soil heterogeneity and the distribution of native grasses in California: Can soil properties inform restoration plans? Ecosphere 5(4):46. http://dx.doi.org/10.1890/ES13-00377.1 Abstract. When historical vegetation patterns are unknown and local environments are highly degraded, the relationship between plant species distributions and environmental properties may provide a means to determine which species are suitable for individual restoration sites. We investigated the role of edaphic variation in explaining the distributions of three native bunchgrass species (Bromus carinatus, Elymus glaucus and Nassella pulchra) among central California mainland and island grasslands. The relative contribution of soil properties and spatial variation to native grass species abundance was estimated using canonical redundancy analysis, with subsequent testing of individual variables identified in ordination. Soil variables predicted a significant proportion (22–27%) of the variation in species distributions. Abiotic soil properties that drive species distributions included serpentine substrates and soil texture. Biotic properties that correlated with species distributions were ammonium and nitrogen mineralization rates. Spatial autocorrelation also contributed to species presence or absence at each site, and the significant negative autocorrelation suggested that species interactions and niche differentiation may play a role in species distributions in central California mainland and island grasslands. We explored the application of plant-environment relationships to ecological restoration for species selection at locations where degradation levels are high and historical communities are unclear. -

Product: 594 - Pollens - Grasses, Bahia Grass Paspalum Notatum

Product: 594 - Pollens - Grasses, Bahia Grass Paspalum notatum Manufacturers of this Product Antigen Laboratories, Inc. - Liberty, MO (Lic. No. 468, STN No. 102223) Greer Laboratories, Inc. - Lenoir, NC (Lic. No. 308, STN No. 101833) Hollister-Stier Labs, LLC - Spokane, WA (Lic. No. 1272, STN No. 103888) ALK-Abello Inc. - Port Washington, NY (Lic. No. 1256, STN No. 103753) Allermed Laboratories, Inc. - San Diego, CA (Lic. No. 467, STN No. 102211) Nelco Laboratories, Inc. - Deer Park, NY (Lic. No. 459, STN No. 102192) Allergy Laboratories, Inc. - Oklahoma City, OK (Lic. No. 103, STN No. 101376) Search Strategy PubMed: Grass Pollen Allergy, immunotherapy; Bahia grass antigens; Bahia grass Paspalum notatum pollen allergy Google: Bahia grass allergy; Bahia grass allergy adverse; Bahia grass allergen; Bahia grass allergen adverse; same search results performed for Paspalum notatum Nomenclature According to ITIS, the scientific name is Paspalum notatum. Common names are Bahia grass and bahiagrass. The scientific and common names are correct and current. Varieties are Paspalum notatum var. notatum and Paspalum notatum var. saurae. The Paspalum genus is found in the Poaceae family. Parent Product 594 - Pollens - Grasses, Bahia Grass Paspalum notatum Published Data Panel I report (pg. 3124) lists, within the tribe Paniceae, the genus Paspalum, with a common name of Dallis. On page 3149, one controlled study (reference 42: Thommen, A.A., "Asthma and Hayfever in theory and Practice, Part 3, Hayfever" Edited by Coca, A.F., M. Walzer and A.A. Thommen, Charles C. Thomas, Springfield IL, 1931) supported the effectiveness of Paspalum for diagnosis. Papers supporting that Bahia grass contains unique antigens that are allergenic (skin test positive) are PMIDs. -

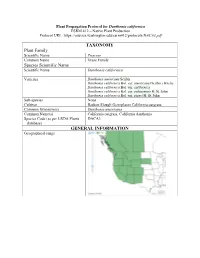

Draft Plant Propagation Protocol

Plant Propagation Protocol for Danthonia californica ESRM 412 – Native Plant Production Protocol URL: https://courses.washington.edu/esrm412/protocols/DACA3.pdf TAXONOMY Plant Family Scientific Name Poaceae Common Name Grass Family Species Scientific Name Scientific Name Danthonia californica Varieties Danthonia americana Scribn. Danthonia californica Bol. var. americana (Scribn.) Hitchc. Danthonia californica Bol. var. californica Danthonia californica Bol. var. palousensis H. St. John Danthonia californica Bol. var. piperi H. St. John Sub-species None Cultivar Baskett Slough Germplasm California oatgrass Common Synonym(s) Danthonia americana Common Name(s) California oatgrass, California danthonia Species Code (as per USDA Plants DACA3 database) GENERAL INFORMATION Geographical range Ecological distribution Danthonia californica occurs in prairies, mid-elevation meadows, forests and transitional wetland habitats. Climate and elevation range Grows from sea level up to 7,000 feet. Danthonia californica grows in a moist environment ranging from 17 to 79 inches annually. They also grow in areas that have a cold winter. Local habitat and abundance Danthonia californica can be found with many other native vegetation on the south Puget Sound prairie and in the northern Puget lowlands. Common species found with Danthonia californica are Deschampsia cespitosa and Elymus glaucus. Plant strategy type / successional Danthonia californica is an early successional plant stage that can live in a myriad of conditions. These conditions can range in precipitation, soil pH, grazing, and soil drainage. It produces cleistogenes, which are self-pollinated seeds that are produced from flowers that do not open, as an adaption to live in stressful conditions. Danthonia californica is a fire adapted plant. Plant characteristics This is a grass that is adapted to fire. -

City of Albany Native Plant List

City of Albany Native Plant List Trees Scientific Name Common Name Abies grandis Grand Fir Acer circinatum Vine Maple Acer macrophyllum Big-leaf Maple Alnus rhombifolia* White Alder Alnus rubra Red Alder Arbutus menziesii Madrone Cornus nuttallii Pacific or Western Dogwood Corylus cornuta Hazelnut Crataegus douglasii Black Hawthorn Fraxinus latifolia Oregon Ash Malus fusca, Pyrus fusca Oregon Crabapple Pinus contorta Shore Pine Pinus ponderosa Valley Ponderosa Pine Populus balsamifera ssp. trichocarpa Black Cottonwood Prunus virginiana Common Chokecherry Pseudotsuga menziesii Douglas Fir Quercus garryana Oregon White Oak Rhamnus purshiana Cascara Salix geyeriana Geyer Willow Salix lucida ssp. lasiandra Pacific Willow Salix scouleriana Scouler’s Willow Salix sessilifolia Soft-leaved Willow, River Willow, Northwest Sandbar Willow Salix sitchensis Sitka Willow Taxus brevifolia Pacific/Western Yew Thuja plicata Western Red Cedar Tsuga heterophylla Western Hemlock Shrubs Scientific Name Common Name Amelanchier alnifolia Serviceberry Cornus sericea Red-Osier Dogwood Gaultheria shallon Salal Holodiscus discolor Ocean spray Lonicera involucrata Black Twinberry Mahonia aquifolium Tall Oregon Grape Mahonia nervosa / Berberis nervosa Dwarf Oregon Grape Oemleria cerasiformis Indian Plum/Osoberry Philadelphus lewisii Mock Orange/ Syringa Physocarpus capitatus Pacific Ninebark Polystichum munitum Sword Fern Prunus emarginata Bitter Cherry Ribes sanguineum Red Flowering Currant EXHIBIT H: City of Albany Native Plant List 1 - 1 for 9/28/2011 City Council -

Siberian Wild Rye Elymus Sibiricus L

Siberian wild rye Elymus sibiricus L. Synonyms: Clinelymus sibiricus (L. J.) Nevski., C. yubaridakensis Honda, Elymus krascheninnikovii Roshev., E. pendulosus Hodgson., E. praetevisus Steud., E. sibiricus var. brachstachys Keng, E. sibiricus var. gracilis L. B. Cai, E. tener L., E. yubaridakensis (Honda) Ohwi, Hordeum sibiricum (L.) Schenck, Triticum arktasianum Hermann. Other common names: Siberian black-eyed Susan Family: Poaceae Invasiveness Rank: 53 The invasiveness rank is calculated based on a species’ ecological impacts, biological attributes, distribution, and response to control measures. The ranks are scaled from 0 to 100, with 0 representing a plant that poses no threat to native ecosystems and 100 representing a plant that poses a major threat to native ecosystems. Note on Native Status: Multiple authors have considered at least some populations of Siberian wild rye to be native to North America, and this species has been recommended as a native, winterhardy, high yield forage crop in Alaska (Bowden and Cody 1961, Klebesadel 1993, Bennett 2006). However, North American populations show no genetic variation and are located in areas historically associated with human travel, agricultural experimentation, and revegetation after fire. Therefore, Siberian wild rye is most likely a non-native grass that was recently introduced to Alaska and northwestern Canada from Russia or central Asia (Bennett 2006, Barkworth et al. 2007). Description Siberian wild rye is a tufted or occasionally rhizomatous, perennial grass that grows from 40 to 150 cm tall. Stems are erect or slightly decumbent at the base, thick, uniformly-leaved, and smooth with exposed nodes. Sheathes are glabrous or slightly hairy and often purple-tinted. -

Plant Guide for California Oatgrass

Plant Guide moist lowland prairies as well as open woodlands. CALIFORNIA Therefore, it is commonly recommended for revegetation, wildlife plantings, and restoration of OATGRASS oak savannas, transitional wetlands, and grasslands, especially in the Pacific Coast states where it is most Danthonia californica common. Bolander Plant Symbol = DACA3 Native bunchgrasses like California oatgrass are valuable for enhancing biodiversity. Healthy stands Contributed by: NRCS Plant Materials Center, can reduce invasion by exotic species yet exhibit a Corvallis, Oregon spatial distribution compatible with forbs (Maslovat 2001). Combined with other native grasses and forbs, California oatgrass improves habitat diversity for feeding, nesting, and hiding by songbirds (Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife 2000), as well as other animals. The grains are eaten by small birds and mammals (Mohlenbrock 1992). Prairies with California oatgrass as a definitive species are also unique refuges for other endemic organisms. For example, the Ohlone tiger beetle (Cicindela ohlone) is an endangered (federally listed) predatory insect known only to five remnant stands of California native grassland in Santa Cruz County (Santa Cruz Public Libraries 2003). These rare grasslands, including the coastal terrace prairies, remain biodiversity “hotspots” and are considered in need of protection (Stromberg et al. 2001). Forage: As a rangeland plant, California oatgrass is well utilized by livestock and certain wildlife. Prior to maturity, the species is rated as good to very good forage for cattle and horses in the Pacific Coast states, but less palatable for sheep and goats. Ratings are lower for eastern, drier portions of its natural range (USDA Forest Service 1988). Others claim it is palatable to all classes of livestock and a mainstay grass for range grazing in places like Humboldt County, California (Cooper 1960). -

Establishment of a Native Seed Industry for the West Coast of Vancouver Island

NATIVE GRASS SEED DEVELOPMENT – PROGRESS AFTER EIGHT YEARS Manivalde Vaartnou Ph.D., P.Ag. M. Vaartnou & Associates 11520 Kestrel Drive Richmond, B.C. V7E 4E2 604-271-2505 E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT Sound ecological restoration of disturbed areas includes the use of native species in the herbaceous layer. However, seed of grasses native to the west coast of British Columbia is neither available in sufficient quantity, nor at a reasonable price. Thus, in 1996 this long-term applied research program was initiated to determine the utility of native Vancouver Island grasses in restoration of disturbed areas, and ultimately provide a source of native grass seed for use on Vancouver Island and the adjacent mainland coast. The program is also a prototype for more recently initiated programs for development of native grass seed supplies for northwest Canada and the southern interior of British Columbia. Native grass seed was collected from the wild during the summers of 1996 and 1997. These seeds were sown to flats in the U.B.C. greenhouse. Subsequently the emergent plants were transplanted to a nursery near Duncan to multiply the seed so that the ensuing parts of the program could be undertaken. Replicated trial sites with agronomic controls were established throughout Vancouver Island. Other sites, which could not be replicated because of a lack of homogeneity in site characteristics, were established as demonstration sites, or larger operational sites. Each summer, the ground cover on all sites has been analyzed on a species by species basis using the ‘Daubenmire’ methodology. This analysis has indicated that native grasses produce at least as much ground cover as introduced, commercially available agronomic grasses. -

California Grasslands and Range Forage Grasses

CALIFORNIA GRASSLANDS AND RANGE FORAGE GRASSES ARTHUR W. SAMPSON AGNES CHASE DONALD W. HEDRICK BULLETIN 724 MAY, 1951 CALIFORNIA AGRICULTURAL EXPERIMENT STATION i THE COLLEGE OF AGRICULTURE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA . CALIFORNIA GRASSLANDS AND RANGE FORAGE GRASSES provides useful and technical information on the uncultivated or wild grass- lands, and the native and naturalized range forage grasses of California. This bulletin will be helpful to you if you are among these readers: 1 Stockmen who have had some botanical training and who will want to use the illustrated keys and descriptions to determine the identity and the relative usefulness of the grasses growing on their range; 2. Range technicians and range appraisers who are chiefly concerned with management, evaluations, and economic considerations of the state's range lands; and 3. Students of range management and related fields whose knowl- edge of ecology, forage value, and taxonomy of the range grasses is an essential part of their training or official work. THE AUTHORS: Arthur W. Sampson is Professor of Forestry and Plant Ecologist in the Experiment Station, Berkeley. Agnes Chase is Research Associate, U. S. National Herbarium, Smithsonian Institu- tion; formerly Senior Agrostologist, U. S. Department of Agriculture. Donald W. Hedrick is Research Assistant in the Department of Forestry; on leave from the Soil Conservation Service, U. S. Department of Agriculture. Manuscript submitted for publication August 22, 1949. CONTENTS PAGE Introduction . 5 Where Grasses Grow 7 Topography, climate, grassland soils, life zones, grasslands in relation to other plant associations Plant Succession and the Climax Cover 17 The Nutrition of Range Grasses 18 Annual vs. -

Plant Identification of Younger Lagoon Reserve

Plant Identification of Younger Lagoon Reserve A guide written by Rebecca Evans with help from Dr. Karen Holl, Elizabeth Howard, and Timothy Brown 1 Table of Contents Introduction to Plant Identification ............................................................................................. 3 Plant Index ................................................................................................................................. 6 Botanical Terminology ............................................................................................................. 12 Habits, Stem Conditions, Root Types ................................................................................ 12 Leaf Parts .......................................................................................................................... 13 Stem Features .................................................................................................................... 14 Leaf Arrangements ............................................................................................................ 16 Leaf Shape ........................................................................................................................ 18 Leaf Margins and Venation ............................................................................................... 20 Flowers and Inflorescences ................................................................................................ 21 Grasses ............................................................................................................................. -

I INDIVIDUALISTIC and PHYLOGENETIC PERSPECTIVES ON

INDIVIDUALISTIC AND PHYLOGENETIC PERSPECTIVES ON PLANT COMMUNITY PATTERNS Jeffrey E. Ott A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Biology Chapel Hill 2010 Approved by: Robert K. Peet Peter S. White Todd J. Vision Aaron Moody Paul S. Manos i ©2010 Jeffrey E. Ott ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Jeffrey E. Ott Individualistic and Phylogenetic Perspectives on Plant Community Patterns (Under the direction of Robert K. Peet) Plant communities have traditionally been viewed as spatially discrete units structured by dominant species, and methods for characterizing community patterns have reflected this perspective. In this dissertation, I adopt an an alternative, individualistic community characterization approach that does not assume discreteness or dominant species importance a priori (Chapter 2). This approach was used to characterize plant community patterns and their relationship with environmental variables at Zion National Park, Utah, providing details and insights that were missed or obscure in previous vegetation characterizations of the area. I also examined community patterns at Zion National Park from a phylogenetic perspective (Chapter 3), under the assumption that species sharing common ancestry should be ecologically similar and hence be co-distributed in predictable ways. I predicted that related species would be aggregated into similar habitats because of phylogenetically-conserved niche affinities, yet segregated into different plots because of competitive interactions. However, I also suspected that these patterns would vary between different lineages and at different levels of the phylogenetic hierarchy (phylogenetic scales). I examined aggregation and segregation in relation to null models for each pair of species within genera and each sister pair of a genus-level vascular plant iii supertree.