A Censorious Analysis of Ghana's Decolonization Process

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Immediate and Long-Term Effects of Namibia's Colonization Process

The Immediate and Long-Term Effects of Namibia’s Colonization Process By: Jonathan Baker Honors Capstone Through Professor Taylor Politics of Sub-Saharan Africa Baker, 2 Table of Contents I. Authors Note II. Introduction III. Pre-Colonization IV. Colonization by Germany V. Colonization by South Africa VI. The Struggle for Independence VII. The Decolonization Process VIII. Political Changes- A Reaction to Colonization IX. Immediate Economic Changes Brought on by Independence X. Long Term Political Effects (of Colonization) XI. Long Term Cultural Effects XII. Long Term Economic Effects XIII. Prospects for the Future XIV. Conclusion XV. Bibliography XVI. Appendices Baker, 3 I. Author’s Note I learned such a great deal from this entire honors capstone project, that all the knowledge I have acquired can hardly be covered by what I wrote in these 50 pages. I learned so much more that I was not able to share both about Namibia and myself. I can now claim that I am knowledgeable about nearly all areas of Namibian history and life. I certainly am no expert, but after all of this research I can certainly consider myself reliable. I have never had such an extensive knowledge before of one academic area as a result of a school project. I also learned a lot about myself through this project. I learned how I can motivate myself to work, and I learned how I perform when I have to organize such a long and complicated paper, just to name a couple of things. The strange inability to be able to include everything I learned from doing this project is the reason for some of the more random appendices at the end, as I have a passion for both numbers and trivia. -

The Impact of the Second World War on the Decolonization of Africa

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU 17th Annual Africana Studies Student Research Africana Studies Student Research Conference Conference and Luncheon Feb 13th, 1:30 PM - 3:00 PM The Impact of the Second World War on the Decolonization of Africa Erin Myrice Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/africana_studies_conf Part of the African Languages and Societies Commons Myrice, Erin, "The Impact of the Second World War on the Decolonization of Africa" (2015). Africana Studies Student Research Conference. 2. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/africana_studies_conf/2015/004/2 This Event is brought to you for free and open access by the Conferences and Events at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Africana Studies Student Research Conference by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. The Impact of the Second World War on the Decolonization of Africa Erin Myrice 2 “An African poet, Taban Lo Liyong, once said that Africans have three white men to thank for their political freedom and independence: Nietzsche, Hitler, and Marx.” 1 Marx raised awareness of oppressed peoples around the world, while also creating the idea of economic exploitation of living human beings. Nietzsche created the idea of a superman and a master race. Hitler attempted to implement Nietzsche’s ideas into Germany with an ultimate goal of reaching the whole world. Hitler’s attempted implementation of his version of a ‘master race’ led to one of the most bloody, horrific, and destructive wars the world has ever encountered. While this statement by Liyong was bold, it held truth. The Second World War was a catalyst for African political freedom and independence. -

Decolonization and Violence in Southeast Asia Crises of Identity and Authority

KARL HACK Decolonization and violence in Southeast Asia Crises of identity and authority How far did Southeast Asia’s experience of colonialism and decolonization contribute to severe postcolonial problems, notably: high levels of violence and endemic crises of authority? There can be no denying that colonialism left plural societies in countries such as Malaysia and Singapore, and that countries such as Indonesia and the Philippines attempted to bolt together very different regions and groups of people. These divisions were to breed violence as far apart as Myanmar and New Guinea, and Aceh and Mindanao. Much of Southeast Asia also experienced an intense period of Japanese era and occupation in the years just before independence. The Japanese conquest of 1941 to 1945 propagandized and mobilized people, promoted quasi- militaristic values, and left in its wake large groups, some with military train- ing or even weapons. In many cases the use of force, or threat of force, also expedited decolonization, further legitimizing the use of violence in resolving disputes over national authority and identity. It is easy to establish that there were traumas and violent experiences in colonialism and in decolonization. But demonstrating how these fed through to the postcolonial period is difficult in the extreme. Was the legacy a region- wide one of visceral divisions that demanded, and still demand, either fissure or authoritarian government? Are the successor states, as governments as varied as Singapore and Myanmar claim, young, fragile creations where authority remains fragile even after five decades or more? This chapter reflects on a number of approaches to explaining the persistence of crises and their links to the colonial and decolonizing eras. -

African Dialects

African Dialects • Adangme (Ghana ) • Afrikaans (Southern Africa ) • Akan: Asante (Ashanti) dialect (Ghana ) • Akan: Fante dialect (Ghana ) • Akan: Twi (Akwapem) dialect (Ghana ) • Amharic (Amarigna; Amarinya) (Ethiopia ) • Awing (Cameroon ) • Bakuba (Busoong, Kuba, Bushong) (Congo ) • Bambara (Mali; Senegal; Burkina ) • Bamoun (Cameroons ) • Bargu (Bariba) (Benin; Nigeria; Togo ) • Bassa (Gbasa) (Liberia ) • ici-Bemba (Wemba) (Congo; Zambia ) • Berba (Benin ) • Bihari: Mauritian Bhojpuri dialect - Latin Script (Mauritius ) • Bobo (Bwamou) (Burkina ) • Bulu (Boulou) (Cameroons ) • Chirpon-Lete-Anum (Cherepong; Guan) (Ghana ) • Ciokwe (Chokwe) (Angola; Congo ) • Creole, Indian Ocean: Mauritian dialect (Mauritius ) • Creole, Indian Ocean: Seychelles dialect (Kreol) (Seychelles ) • Dagbani (Dagbane; Dagomba) (Ghana; Togo ) • Diola (Jola) (Upper West Africa ) • Diola (Jola): Fogny (Jóola Fóoñi) dialect (The Gambia; Guinea; Senegal ) • Duala (Douala) (Cameroons ) • Dyula (Jula) (Burkina ) • Efik (Nigeria ) • Ekoi: Ejagham dialect (Cameroons; Nigeria ) • Ewe (Benin; Ghana; Togo ) • Ewe: Ge (Mina) dialect (Benin; Togo ) • Ewe: Watyi (Ouatchi, Waci) dialect (Benin; Togo ) • Ewondo (Cameroons ) • Fang (Equitorial Guinea ) • Fõ (Fon; Dahoméen) (Benin ) • Frafra (Ghana ) • Ful (Fula; Fulani; Fulfulde; Peul; Toucouleur) (West Africa ) • Ful: Torado dialect (Senegal ) • Gã: Accra dialect (Ghana; Togo ) • Gambai (Ngambai; Ngambaye) (Chad ) • olu-Ganda (Luganda) (Uganda ) • Gbaya (Baya) (Central African Republic; Cameroons; Congo ) • Gben (Ben) (Togo -

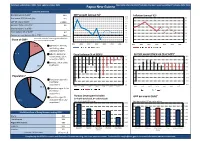

Papua New Guinea

Factsheet updated April 2021. Next update October 2021. Papua New Guinea Most data refers to 2019 (*indicates the most recent available) (~indicates 2020 data) Economic Overview Nominal GDP ($US bn)~ 23.6 GDP growth (annual %)~ 16.0 Inflation (annual %)~ 8.0 Real annual GDP Growth (%)~ -3.9 14.0 7.0 GDP per capita ($US)~ 2,684.8 12.0 10.0 6.0 Annual inflation rate (%)~ 5.0 8.0 5.0 Unemployment rate (%)~ - 6.0 4.0 4.0 Fiscal balance (% of GDP)~ -6.2 2.0 3.0 Current account balance (% of GDP)~ 0.0 13.9 2.0 -2.0 Due to the method of estimating value added, pie 1 1.0 Share of GDP* chart may not add up to 100% -4.0 1 -6.0 0.0 2013 2015 2017 2019 2021 2023 2025 2013 2015 2017 2019 2021 2023 2025 1 17.0 Agriculture, forestry, 1 and fishing, value added (% of GDP) 1 41.6 Industry (including Fiscal balance (% of GDP)~ Current account balance (% of GDP)~ 1 construction), value 0.0 40.0 1 added (% of GDP) -1.0 30.0 1 Services, value added -2.0 20.0 1 36.9 (% of GDP) -3.0 10.0 1 -4.0 0.0 1 -5.0 -10.0 Population*1 -6.0 -20.0 1 3.5 Population ages 0-14 -7.0 -30.0 1 (% of total population) -8.0 -40.0 1 35.5 2013 2015 2017 2019 2021 2023 2025 2013 2015 2017 2019 2021 2023 2025 Population ages 15-64 1 (% of total 1 population) 1 Human Development Index Population ages 65 GDP per capita ($US)~ (1= highly developed, 0= undeveloped) 61.0 1 and above (% of total Data label is global HDI ranking Data label is global GDP per capita ranking 1 population) 0.565 3,500 1 0.560 3,000 1 2,500 0.555 World Bank Ease of Doing Business ranking 2020 2,000 0.550 Ghana 118 1,500 0.545 The Bahamas 119 1,000 Papua New Guinea 120 0.540 500 153 154 155 156 157 126 127 128 129 130 Eswatini 121 0.535 0 Cameroon Pakistan Papua New Comoros Mauritania Vanuatu Lebanon Papua New Laos Solomon Islands Lesotho 122 Guinea Guinea 1 is the best, 189 is the worst UK rank is 8 Compiled by the FCDO Economics and Evaluation Directorate using data from external sources. -

Ghana, Lesotho, and South Africa: Regional Expansion of Water Supply in Rural Areas

Ghana, Lesotho, and South Africa: Regional Expansion of Water Supply in Rural Areas Water, sanitation, and hygiene are essential for achieving all the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and hence for contributing to poverty eradication globally. This case study contributes to the learning process on scaling up poverty reduction by describing and analyzing three programs in rural water and sanitation in Africa: the national rural water sector reform in Ghana, the national water and sanitation program in South Africa, and the national sanitation program in Lesotho. These national programs have made significant progress towards poverty elimination through improved water and sanitation. Although they are all different, there are several general conclusions that can validly be drawn from them: · Top-level political commitment to water and sanitation, sustained consistently over a long time period, is critically important to the success of national sector programs. · Clear legislation is necessary to give guidance and confidence to all the agencies working in the sector. · Devolution of authority from national to local government and communities improves the accountability of water and sanitation programs. · The involvement of a wide range of local institutions—social, economic, civil society, and media — empowers communities and stimulates development at the local scale. · The sensitive, flexible, and country-specific support of external agencies can add significant momentum to progress in the water and sanitation sector. Background and context Over the past decade, the rural water and sanitation sector in Ghana has been transformed from a centralized supply-driven model to a system in which local government and communities plan together, communities operate and maintain their own water services, and the private sector is active in providing goods and services. -

The Changing Face of Money: Preferences for Different Payment Forms in Ghana and Zambia

The Changing Face of Money: Preferences for Different Payment Forms in Ghana and Zambia Vivian A. Dzokoto Virginia Commonwealth University Elizabeth N. Appiah Pentecost University College Laura Peters Chitwood Counseling & Advocacy Associates Mwiya L. Imasiku University of Zambia Mobile Money (MM) is now a popular medium of exchange and store of value in parts of Africa, Latin America and Asia. As payment modalities emerge, consumer preferences for different payment tools evolve. Our study examines the preference for, and use of MM and other payment forms in both Ghana and Zambia. Our multi-method investigation indicates that while MM preference and awareness is high, scope of use is low in Ghana and Zambia. Cash remains the predominant mode of business transaction in both countries. Increased merchant acceptability is needed to improve the MM ecology in these countries. 1. INTRODUCTION The materiality of money has evolved over time, evidenced by the emergence of debit and credit cards in the twentieth century (Borzekowski and Kiser, 2008; Schuh and Stavins, 2010). Currently, mobile forms of payment are reaching widespread use in many regions of Sub-Saharan Africa, which is the fastest growing market for mobile phones worldwide (International Telecommunication Union [ITU], 2009). For example, M-Pesa is an extremely popular form of mobile payment in Kenya, possibly due to structural and cultural factors (Omwansa and Sullivan, 2012). However, no major form of money from the twentieth century has been completely phased out, as people exercise preferences for which form of money to use. Based on the evolution of payment methods, the current study explores perceptions and utilization of Mobile Money (MM) in Ghana, West Africa and in Zambia, South-Central Africa. -

Non-Alignment in Indonesia - Cold War Or Decolonization?

Non-Alignment in Indonesia - Cold War or Decolonization? This module is designed for students to examine the Non-Aligned Movement in Indonesia to determine how it reflects the historical developments of the Cold War and Decolonization. FOCUS QUESTION: How does the Cold War and Decolonization impact Indonesian international relations in the twentieth century? AP Curriculum Framework Alignment Task: Based on a 60 minute class Unit 8 - Cold War and Decolonization Historical Thinking Skills: Developments and Processes - Explain a historical concept, development, or process. Making Connections - Explain how a historical development or process relates to another historical development or process. Sourcing and Situation - Explain the point of view, purpose, historical situation, and/or audience of a source. Topic: 8.2 The Cold War Topic: 8.5 Decolonization After 1900 Thematic Focus: Cultural Developments and Interactions - Thematic Focus: Government - A variety of internal and The development of ideas, beliefs, and religions illustrate how external factors contribute to state formation, expansion, and groups in society view themselves, and the interactions of decline. Governments maintain order through a variety of societies and their beliefs often have political, social, and administrative institutions, policies, and procedures, and cultural implications. governments obtain, retain, and exercise power in different ways Learning Objective: Explain the causes and effects of the and for different purposes. ideological struggle of the Cold War. Learning Objective: Compare the processes by which peoples Historical Developments KC-6.2.V.B: Groups and individuals, pursued independence after 1900. including the Non-Aligned Movement, opposed and promoted Historical Developments KC-6.2.II.A - Nationalist leaders and alternatives to the existing economic, political, and social parties in Asia and Africa sought varying degrees of autonomy orders. -

Black Internationalism and African and Caribbean

BLACK INTERNATIONALISM AND AFRICAN AND CARIBBEAN INTELLECTUALS IN LONDON, 1919-1950 By MARC MATERA A Dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in History Written under the direction of Professor Bonnie G. Smith And approved by _______________________ _______________________ _______________________ _______________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey May 2008 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Black Internationalism and African and Caribbean Intellectuals in London, 1919-1950 By MARC MATERA Dissertation Director: Bonnie G. Smith During the three decades between the end of World War I and 1950, African and West Indian scholars, professionals, university students, artists, and political activists in London forged new conceptions of community, reshaped public debates about the nature and goals of British colonialism, and prepared the way for a revolutionary and self-consciously modern African culture. Black intellectuals formed organizations that became homes away from home and centers of cultural mixture and intellectual debate, and launched publications that served as new means of voicing social commentary and political dissent. These black associations developed within an atmosphere characterized by a variety of internationalisms, including pan-ethnic movements, feminism, communism, and the socialist internationalism ascendant within the British Left after World War I. The intellectual and political context of London and the types of sociability that these groups fostered gave rise to a range of black internationalist activity and new regional imaginaries in the form of a West Indian Federation and a United West Africa that shaped the goals of anticolonialism before 1950. -

Gold, Labor and Colonialism in the Late-Nineteenth Century Gold Coast

Raymond E. Dumett. El Dorado in West Africa: The Gold-Mining Frontier, African Labor, and Colonial Capitalism in the Gold Coast, 1875-1900. Athens: Ohio University Press, 1999. xviii + 396 pp. $24.95, paper, ISBN 978-0-8214-1198-8. Reviewed by Andrew F. Clark Published on H-Africa (August, 1999) The later nineteenth century witnessed the capitalistic gold mining. He examines various his‐ most extensive and famous series of gold migra‐ toriographical questions and provides consider‐ tions in modern history. Gold rushes occurred in able new information on the topics of mining, la‐ different parts of the world, including California, bor relations, capitalism, and colonialism in Southern Africa, Australia, New Zealand, Alaska, southwestern Ghana. The high quality photo‐ and the southwestern Gold Coast of West Africa. graphs at the end of each chapter depicting both Each of the gold discoveries caused large migra‐ indigenous and expatriate gold mining are a valu‐ tions of prospectors, skilled laborers, engineers, able addition to the book. land speculators, share pushers and con artists Gold mining and trading predated the arrival who moved from one fnd to the next, bringing of Europeans. The Akan region was one of West with them various skills but all with one goal, Africa's major gold sources, along with Bambuhu profit. In this excellent account focused on the on the upper Senegal and Bure on the upper Wassa area of the southwestern Gold Coast, Ray‐ Niger, for the trans-Saharan trade. West African mond Dumett, who has published extensively on gold made its way to medieval and Renaissance the colonial period and on gold mining, explores Europe. -

Colonialism and Economic Development in Africa

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES COLONIALISM AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT IN AFRICA Leander Heldring James A. Robinson Working Paper 18566 http://www.nber.org/papers/w18566 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 November 2012 We are grateful to Jan Vansina for his suggestions and advice. We have also benefitted greatly from many discussions with Daron Acemoglu, Robert Bates, Philip Osafo-Kwaako, Jon Weigel and Neil Parsons on the topic of this research. Finally, we thank Johannes Fedderke, Ewout Frankema and Pim de Zwart for generously providing us with their data. The views expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer- reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2012 by Leander Heldring and James A. Robinson. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Colonialism and Economic Development in Africa Leander Heldring and James A. Robinson NBER Working Paper No. 18566 November 2012 JEL No. N37,N47,O55 ABSTRACT In this paper we evaluate the impact of colonialism on development in Sub-Saharan Africa. In the world context, colonialism had very heterogeneous effects, operating through many mechanisms, sometimes encouraging development sometimes retarding it. In the African case, however, this heterogeneity is muted, making an assessment of the average effect more interesting. -

THE ACQUISITION of SLAVES Portuguese Exploration in The

CHAPTER TWO THE ACQUISITION OF SLAVES Portuguese exploration in the Atlantic in the fifteenth century her- alded a shift in emphasis in the African slave trade from the Sahara to the West African coast. As outlined in the Introduction, the slave trade focused first on Arguim and Elmina, but during the late six- teenth century Upper Guinea developed as the main centre of the trade. Meanwhile in the early seventeenth century the conquest of Angola laid the basis for the development of the slave trade in that region. It was thus during the period of the Portuguese asientos that Upper Guinea began to lose its dominance in the trade to Angola. Manuel Bautista Pérez acquired slaves from both Upper Guinea and Angola. He was personally involved in the acquisition of slaves in Upper Guinea on two slave-trading expeditions to the Coast between 1613 and 1618, but as far as we know he never visited Angola. Following these two expeditions he settled in the Indies and largely relied on agents in Cartagena to acquire slaves for him. Between 1626 and 1633 his agents in Cartagena purchased 2,451 slaves of which 48.4 percent came from Upper Guinea and 45.8 percent from Angola.1 Pérez’s early expeditions to the African coast were a learning process for the young slave trader and they gener- ated a considerable volume of papers that included not only trad- ing accounts but also many private letters. The evidence contained in these documents adds considerable detail to what is known about slave-trading operations on the Upper Guinea Coast in the early seventeenth century from the general observations of merchants, trav- ellers and missionaries.