The Canaanite and Nubian Wars of Merenptah: Some Historical Notes Mohamed Raafat Abbas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Canaan Or Gaza?

Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections Pa-Canaan in the Egyptian New Kingdom: Canaan or Gaza? Michael G. Hasel Institute of Archaeology, Southern Adventist University A&564%'6 e identification of the geographical name “Canaan” continues to be widely debated in the scholarly literature. Cuneiform sources om Mari, Amarna, Ugarit, Aššur, and Hattusha have been discussed, as have Egyptian sources. Renewed excavations in North Sinai along the “Ways of Horus” have, along with recent scholarly reconstructions, refocused attention on the toponyms leading toward and culminating in the arrival to Canaan. is has led to two interpretations of the Egyptian name Pa-Canaan: it is either identified as the territory of Canaan or the city of Gaza. is article offers a renewed analysis of the terms Canaan, Pa-Canaan, and Canaanite in key documents of the New Kingdom, with limited attention to parallels of other geographical names, including Kharu, Retenu, and Djahy. It is suggested that the name Pa-Canaan in Egyptian New Kingdom sources consistently refers to the larger geographical territory occupied by the Egyptians in Asia. y the 1960s, a general consensus had emerged regarding of Canaan varied: that it was a territory in Asia, that its bound - the extent of the land of Canaan, its boundaries and aries were fluid, and that it also referred to Gaza itself. 11 He Bgeographical area. 1 The primary sources for the recon - concludes, “No wonder that Lemche’s review of the evidence struction of this area include: (1) the Mari letters, (2) the uncovered so many difficulties and finally led him to conclude Amarna letters, (3) Ugaritic texts, (4) texts from Aššur and that Canaan was a vague term.” 12 Hattusha, and (5) Egyptian texts and reliefs. -

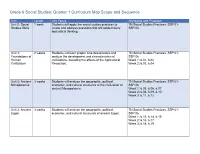

Grade 6 Social Studies: Quarter 1 Curriculum Map Scope and Sequence

Grade 6 Social Studies: Quarter 1 Curriculum Map Scope and Sequence Unit Length Unit Focus Standards and Practices Unit 0: Social 1 week Students will apply the social studies practices to TN Social Studies Practices: SSP.01- Studies Skills create and address questions that will guide inquiry SSP.06 and critical thinking. Unit 1: 2 weeks Students will learn proper time designations and TN Social Studies Practices: SSP.01- Foundations of analyze the development and characteristics of SSP.06 Human civilizations, including the effects of the Agricultural Week 1: 6.01, 6.02 Civilization Revolution. Week 2: 6.03, 6.04 Unit 2: Ancient 3 weeks Students will analyze the geographic, political, TN Social Studies Practices: SSP.01- Mesopotamia economic, and cultural structures of the civilization of SSP.06 ancient Mesopotamia. Week 1: 6.05, 6.06, 6.07 Week 2: 6.08, 6.09, 6.10 Week 3: 6.11, 6.12 Unit 3: Ancient 3 weeks Students will analyze the geographic, political, TN Social Studies Practices: SSP.01- Egypt economic, and cultural structures of ancient Egypt. SSP.06 Week 1: 6.13, 6.14, 6.15 Week 2: 6.16, 6.17 Week 3: 6.18, 6.19 Grade 6 Social Studies: Quarter 1 Map Instructional Framework Course Description: World History and Geography: Early Civilizations Through the Fall of the Western Roman Empire Sixth grade students will study the beginnings of early civilizations through the fall of the Western Roman Empire. Students will analyze the cultural, economic, geographical, historical, and political foundations for early civilizations, including Mesopotamia, Egypt, Israel, India, China, Greece, and Rome. -

Who Were the Kenites? OTE 24/2 (2011): 414-430

414 Mondriaan: Who were the Kenites? OTE 24/2 (2011): 414-430 Who were the Kenites? MARLENE E. MONDRIAAN (U NIVERSITY OF PRETORIA ) ABSTRACT This article examines the Kenite tribe, particularly considering their importance as suggested by the Kenite hypothesis. According to this hypothesis, the Kenites, and the Midianites, were the peoples who introduced Moses to the cult of Yahwism, before he was confronted by Yahweh from the burning bush. Scholars have identified the Cain narrative of Gen 4 as the possible aetiological legend of the Kenites, and Cain as the eponymous ancestor of these people. The purpose of this research is to ascertain whether there is any substantiation for this allegation connecting the Kenites to Cain, as well as con- templating the Kenites’ possible importance for the Yahwistic faith. Information in the Hebrew Bible concerning the Kenites is sparse. Traits associated with the Kenites, and their lifestyle, could be linked to descendants of Cain. The three sons of Lamech represent particular occupational groups, which are also connected to the Kenites. The nomadic Kenites seemingly roamed the regions south of Palestine. According to particular texts in the Hebrew Bible, Yahweh emanated from regions south of Palestine. It is, therefore, plausible that the Kenites were familiar with a form of Yahwism, a cult that could have been introduced by them to Moses, as suggested by the Kenite hypothesis. Their particular trade as metalworkers afforded them the opportunity to also introduce their faith in the northern regions of Palestine. This article analyses the etymology of the word “Kenite,” the ancestry of the Kenites, their lifestyle, and their religion. -

The Story of the World History for the Classical Child

The Story of the World history for the classical child Volume 1: Ancient Times From the Earliest Nomads to the Last Roman Emperor revised edition with new maps, illustrations, and timelines by Susan Wise Bauer illustrated by Jeff West PEACE HILL PRESS Charles City, VA Peace Hill Press, Charles City, VA 23030 © 2001, 2006 by Susan Wise Bauer All rights reserved. First edition 2001. Second edition 2006. Publisher’s Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bauer, Susan Wise. The story of the world : history for the classical child. Vol. 1, Ancient times : from the earliest nomads to the last Roman emperor / by Susan Wise Bauer ; illustrated by Jeff West.—2nd ed. p. : ill. ; cm. Includes index. ISBN-10: 1-933339-01-2 ISBN-13: 978-1-93339-01-6 ISBN-10 (pbk.): 1-933339-00-4 ISBN-13 (pbk.): 978-1-93339-00-9 1. History, Ancient—Juvenile literature. 2. Greece—History—Juvenile literature. 3. Rome—History—Juvenile literature. 4. History, Ancient. 5. Civilization, Ancient. 6. Greece—History. 7. Rome—History. I. West, Jeff. II. Title. D57 .B38 2006 930 2005909816 Printed in the United States of America Cover design by AJ Buffington and Mike Fretto. Book design by Charlie Park. Composed in Adobe Garamond Pro. For more on illustrator Jeff West, visit jeffwestsart.com. ∞ The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992. www.peacehillpress.com Contents Introduction: How Do We Know What Happened? What Is History? 1 What Is Archaeology? -

Sea Peoples of the Bronze Age Mediterranean C.1400 BC–1000 BC

Sea Peoples of the Bronze Age Mediterranean c.1400 BC–1000 BC RAFFAELE D’AMATO ILLUSTRATED BY GIUSEPPE RAVA & ANDREA SALIMBETI© Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com &MJUFt Sea Peoples of the Bronze Age Mediterranean c.1400 BC–1000 BC ANDREA SALIMBETI ILLUSTRATED BY GIUSEPPE RAVA & RAFFAELE D’AMATO Series editor Martin Windrow © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 4 CHRONOLOGY 6 HISTORICAL BACKGROUND & SOURCES 7 5IFXBSTPG3BNFTTFT** .FSOFQUBIBOE3BNFTTFT*** 0UIFSTPVSDFT IDENTIFICATION OF GROUPS 12 Sherden Peleset 5KFLLFS %FOZFO 4IFLFMFTI &LXFTI Teresh ,BSLJTB-VLLB 8FTIFTI .FSDFOBSZTFSWJDF 1JSBDZ CLOTHING & EQUIPMENT 31 $MPUIJOH %FGFOTJWFFRVJQNFOUIFMNFUToTIJFMEToCPEZBSNPVST 8FBQPOTTQFBSTBOEKBWFMJOToTXPSET EBHHFSTBOENBDFT̓ MILITARY ORGANIZATION 39 $PNQPTJUJPOPGUIFIPTUEFQJDUFEJOUIF.FEJOFU)BCVSFMJFGT Leadership TACTICS 44 8BSDIBSJPUT 4JFHFXBSGBSF /BWBMXBSGBSFBOETFBCPSOFSBJET ‘THE WAR OF THE EIGHTH YEAR’, 1191 OR 1184 BC 49 5IFJOWBTJPO The land battle The sea battle "GUFSNBUI BIBLIOGRAPHY 61 INDEX 64 © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com SEA PEOPLES OF THE BRONZE AGE MEDITERRANEAN c.1400 BC–1000 BC INTRODUCTION The term ‘Sea Peoples’ is given today to various seaborne raiders and invaders from a loose confederation of clans who troubled the Aegean, the Near East and Egypt during the final period of the Bronze Age in the second half of the "QSJTPOFSDBQUVSFECZUIF 2nd millennium BC. &HZQUJBOT QPTTJCMZB1FMFTFU XBSSJPS XFBSJOHBUZQJDBM Though the Egyptians presumably knew the homelands -

A Note Towards Quantifying the Medieval Nubian Diaspora

23 A Note towards Quantifying the Medieval Nubian Diaspora Adam Simmons Throughout the Christian medieval period of the kingdoms of Nu- bia (c. sixth–fifteenth centuries), ideas, goods, and peoples traversed vast distances. Judging from primarily external sources, the Nubian diaspora has seldom been thought of as vast, whether in number or geographical scope, both in terms of the relocated and a non- permanently domiciled diaspora. Prior to the Christianisation of the kingdoms of Nobadia, Makuria, and Alwa in the sixth century, likely Nubian delegations, consisting of “Ethiopes,” were received in both Rome and Constantinople alongside ones from neighbouring peoples, such as the Blemmyes and Aksumites. Yet, medieval Nubia is more often seen as inclusive rather than diasporic. This brief dis- cussion will further show that Nubians were an interactive society within the wider Mediterranean, a topic most commonly seen in the debate on Nubian trade.1 Above all, it argues that Nubians had a long relationship with Mediterranean societies that has primarily been overlooked in scholarship. Whilst the evidence presented here is not aimed to be definitive, it does highlight that Nubia’s Mediterranean connections may even have been more diverse than what Giovan- ni Ruffini argued for in his book Medieval Nubia whilst describing Nubia as a “Mediterranean society in Africa.”2 May we even argue for a more developed thesis of interaction? What about the Nubian societies throughout the Mediterranean who interacted with other communities both spiritually and financially? It will be argued here that these questions should be revisited and have potential to fur- ther expand Ruffini’s Mediterranean thesis. -

Three Conquests of Canaan

ÅA Wars in the Middle East are almost an every day part of Eero Junkkaala:of Three Canaan Conquests our lives, and undeniably the history of war in this area is very long indeed. This study examines three such wars, all of which were directed against the Land of Canaan. Two campaigns were conducted by Egyptian Pharaohs and one by the Israelites. The question considered being Eero Junkkaala whether or not these wars really took place. This study gives one methodological viewpoint to answer this ques- tion. The author studies the archaeology of all the geo- Three Conquests of Canaan graphical sites mentioned in the lists of Thutmosis III and A Comparative Study of Two Egyptian Military Campaigns and Shishak and compares them with the cities mentioned in Joshua 10-12 in the Light of Recent Archaeological Evidence the Conquest stories in the Book of Joshua. Altogether 116 sites were studied, and the com- parison between the texts and the archaeological results offered a possibility of establishing whether the cities mentioned, in the sources in question, were inhabited, and, furthermore, might have been destroyed during the time of the Pharaohs and the biblical settlement pe- riod. Despite the nature of the two written sources being so very different it was possible to make a comparative study. This study gives a fresh view on the fierce discus- sion concerning the emergence of the Israelites. It also challenges both Egyptological and biblical studies to use the written texts and the archaeological material togeth- er so that they are not so separated from each other, as is often the case. -

The City of Aššur and the Kingdom of Assyria: Historical Overview

Assurlular Dicle'den Toroslar'a Tann Assur'un Kralhg1 The Assyrians .hm11.dum uf tltc (;,,._[ l ur ltm•J T1g1l '' Trmru~ Assur Kenti ve Assur Krall1g1 Tarihine Genel Baki§ The City of Assur and the Kingdom of Assyria: Historical Overview KAREN RADN ER* Assur medeniyetinin arkeolojik ke~fi MS 19. yüz}'ll ortalannda Tb.: a1< h.tcologu:al discoven ol A•sH ra brWJn m tlat mi•ll\1'1' et·tlf1H Y \0 (L1.rsen l!l\11)) >\1 rhat ume, ba~lamt~tJr (Larsen 1996). 0 zamanlarda Osmanh imparator frcnc h nnd Ar iri~h dip1om m ;md 1racl.- eh if•galt''i sta lugu topraklarmda görev yapan Franstz ve ingiliz diplomatlar uotwrl in thc Olll man Emp1re us d theu spare llme ile ticari temsilciler bo~ zamanlannda Musul kenti ~evresinde 10 c.;xplort' tht• rq~ion .mmnd Iht> < ity ot Mosul :md ke§if gczileri yaparken; inive, Kalhu ve Dur-~arrukin'de ki tlllcU\ercd the r<:mö&ins nftht' tO):&I cilie' ol ~mt wh, k.raliyet kentlerinin k.almulanm ortaya <;tkarmt§lardL Eski K.. ll•u nml Dur-~aa rukcn. Thc• cll~ro\• ry ot a lo5t civ1 Ji?~tinu wr1h .1 ~troug Bihlir .tl comwnion com Ahit ile gü~lü bir baglantlSt olan bu kaytp medeniyetin ke~ cidcd w1th thc creation of gr ancl nun. urns in l'.urs fi, Paris ve Londra'da bir yandan halk1 egiten bir yandan ,tnd l.onrlon tlr.•I '"11~h1 to t>dtiCllll' !Iw puhlic \\lalle da imparatorluklarm dünyayt sarsan gücünü orlaya koyma simuh.m.. uush clemtHISII.tling 1h• impt:tl.tl p<mer s' Y' ama<;layan büyük müzelerin kurulmaslyla aynt zarnanda hold OH'r the wotld, and '\ss} aan galletrc 1\"de Cle ated iu holh tht Lolll~< 31111!111' lhitish l\ ln~cum . -

Amarna Period Down to the Opening of Sety I's Reign

oi.uchicago.edu STUDIES IN ANCIENT ORIENTAL CIVILIZATION * NO.42 THE ORIENTAL INSTITUTE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO Thomas A. Holland * Editor with the assistance of Thomas G. Urban oi.uchicago.edu oi.uchicago.edu Internet publication of this work was made possible with the generous support of Misty and Lewis Gruber THE ROAD TO KADESH A HISTORICAL INTERPRETATION OF THE BATTLE RELIEFS OF KING SETY I AT KARNAK SECOND EDITION REVISED WILLIAM J. MURNANE THE ORIENTAL INSTITUTE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO STUDIES IN ANCIENT ORIENTAL CIVILIZATION . NO.42 CHICAGO * ILLINOIS oi.uchicago.edu Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 90-63725 ISBN: 0-918986-67-2 ISSN: 0081-7554 The Oriental Institute, Chicago © 1985, 1990 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. Published 1990. Printed in the United States of America. oi.uchicago.edu TABLE OF CONTENTS List of M aps ................................ ................................. ................................. vi Preface to the Second Edition ................................................................................................. vii Preface to the First Edition ................................................................................................. ix List of Bibliographic Abbreviations ..................................... ....................... xi Chapter 1. Egypt's Relations with Hatti From the Amarna Period Down to the Opening of Sety I's Reign ...................................................................... ......................... 1 The Clash of Empires -

Empires Text PROOF4 PAGES Copy

TWELVE GREAT BATTLES IN ANTIQUITY STONE TOWER BOOKS AN IMPRINT OF LAMPION PRESS SILVERTON, OR When Empires Clash Copyright © 2015 Patrick Hunt All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the author. The only exception is by a reviewer, who may quote short excerpts in a review. Lampion Press, LLC P. O. Box 932 Silverton, OR 97381 Paperback ISBN: 978-1-942614-12-8 Hardback ISBN: 978-1-942614-13-5 Library of Congress Control Number: 2015956932 Formatting and cover design by Amy Cole, JPL Design Solutions Maps by A. D. Riddle, RiddleMaps.com Front cover illustration: “Battle of Marathon,” (“Schlacht bei Marathon”) by Karl von Rotteck (1842), akg-images.co.uk, Used with permission. Printed in the United States of America Table of ConTenTs Preface ............................................................................................1 ChApTER 1 The Battle of Kadesh (1274 BCE) .................................7 ChApTER 2 The Battle of Nineveh (612 BCE) ................................19 ChApTER 3 The Battle of Marathon (490 BCE) ..............................31 ChApTER 4 The Battle of Issus (333 BCE) .....................................45 ChApTER 5 The Battle of Trebbia (218 BCE) .................................63 ChApTER 6 The Battle of Cannae (216 BCE) .................................77 ChApTER 7 The Battle of Cartagena (209 BCE) .............................95 ChApTER 8 The Battle -

Varieties and Sources of Sandstone Used in Ancient Egyptian Temples

The Journal of Ancient Egyptian Architecture vol. 1, 2016 Varieties and sources of sandstone used in Ancient Egyptian temples James A. Harrell Cite this article: J. A. Harrell, ‘Varieties and sources of sandstone used in Ancient Egyptian temples’, JAEA 1, 2016, pp. 11-37. JAEA www.egyptian-architecture.com ISSN 2472-999X Published under Creative Commons CC-BY-NC 2.0 JAEA 1, 2016, pp. 11-37. www.egyptian-architecture.com Varieties and sources of sandstone used in Ancient Egyptian temples J. A. Harrell1 From Early Dynastic times onward, limestone was the construction material of choice for An- cient Egyptian temples, pyramids, and mastabas wherever limestone bedrock occurred, that is, along the Mediterranean coast, in the northern parts of the Western and Eastern Deserts, and in the Nile Valley between Cairo and Esna (fig. 1). Sandstone bedrock is present in the Nile Valley from Esna south into Sudan as well as in the adjacent deserts, and within this region it was the only building stone employed.2 Sandstone was also imported into the Nile Valley’s limestone region as far north as el-‘Sheikh Ibada and nearby el-‘Amarna, where it was used for New Kingdom tem- ples. There are sandstone temples further north in the Bahariya and Faiyum depressions, but these were built with local materials. The first large-scale use of sandstone occurred near Edfu in Upper Egypt, where it was employed for interior pavement and wall veneer in an Early Dynastic tomb at Hierakonpolis3 and also for a small 3rd Dynasty pyramid at Naga el-Goneima.4 Apart from this latter structure, the earliest use of sandstone in monumental architecture was for Middle Kingdom temples in the Abydos-Thebes region with the outstanding example the 11th Dynasty mortuary temple of Mentuhotep II (Nebhepetre) at Deir el-Bahri. -

Israel's Conquest of Canaan: Presidential Address at the Annual Meeting, Dec

Israel's Conquest of Canaan: Presidential Address at the Annual Meeting, Dec. 27, 1912 Author(s): Lewis Bayles Paton Reviewed work(s): Source: Journal of Biblical Literature, Vol. 32, No. 1 (Apr., 1913), pp. 1-53 Published by: The Society of Biblical Literature Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3259319 . Accessed: 09/04/2012 16:53 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The Society of Biblical Literature is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of Biblical Literature. http://www.jstor.org JOURNAL OF BIBLICAL LITERATURE Volume XXXII Part I 1913 Israel's Conquest of Canaan Presidential Address at the Annual Meeting, Dec. 27, 1912 LEWIS BAYLES PATON HARTFORD THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY problem of Old Testament history is more fundamental NO than that of the manner in which the conquest of Canaan was effected by the Hebrew tribes. If they came unitedly, there is a possibility that they were united in the desert and in Egypt. If their invasions were separated by wide intervals of time, there is no probability that they were united in their earlier history. Our estimate of the Patriarchal and the Mosaic traditions is thus conditioned upon the answer that we give to this question.