Katherine Roet's Swynfords

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Richard II First Folio

FIRST FOLIO Teacher Curriculum Guide Welcome to the Table of Contents Shakespeare Theatre Company’s production Page Number of About the Play Richard II Synopsis of Richard II…..…….….... …….….2 by William Shakespeare Interview with the Director/About the Play…3 Historical Context: Setting the Stage….....4-5 Dear Teachers, Divine Right of Kings…………………..……..6 Consistent with the STC's central mission to Classroom Connections be the leading force in producing and Tackling the Text……………………………...7 preserving the highest quality classic theatre , Before/After the Performance…………..…...8 the Education Department challenges Resource List………………………………….9 learners of all ages to explore the ideas, Etiquette Guide for Students……………….10 emotions and principles contained in classic texts and to discover the connection between The First Folio Teacher Curriculum Guide for classic theatre and our modern perceptions. Richard II was developed by the We hope that this First Folio Teacher Shakespeare Theatre Company Education Curriculum Guide will prove useful as you Department. prepare to bring your students to the theatre! ON SHAKESPEARE First Folio Guides provide information and For articles and information about activities to help students form a personal Shakespeare’s life and world, connection to the play before attending the please visit our website production. First Folio Guides contain ShakespeareTheatre.org, material about the playwrights, their world to download the file and their works. Also included are On Shakespeare. approaches to explore the plays and productions in the classroom before and after the performance. Next Steps If you would like more information on how First Folio Guides are designed as a you can participate in other Shakespeare resource both for teachers and students. -

Download Thesis

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ Fast Horses The Racehorse in Health, Disease and Afterlife, 1800 - 1920 Harper, Esther Fiona Awarding institution: King's College London The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 10. Oct. 2021 Fast Horses: The Racehorse in Health, Disease and Afterlife, 1800 – 1920 Esther Harper Ph.D. History King’s College London April 2018 1 2 Abstract Sports historians have identified the 19th century as a period of significant change in the sport of horseracing, during which it evolved from a sporting pastime of the landed gentry into an industry, and came under increased regulatory control from the Jockey Club. -

Kentucky Derby, Flamingo Stakes, Florida Derby, Blue Grass Stakes, Preakness, Queen’S Plate 3RD Belmont Stakes

Northern Dancer 90th May 2, 1964 THE WINNER’S PEDIGREE AND CAREER HIGHLIGHTS Pharos Nearco Nogara Nearctic *Lady Angela Hyperion NORTHERN DANCER Sister Sarah Polynesian Bay Colt Native Dancer Geisha Natalma Almahmoud *Mahmoud Arbitrator YEAR AGE STS. 1ST 2ND 3RD EARNINGS 1963 2 9 7 2 0 $ 90,635 1964 3 9 7 0 2 $490,012 TOTALS 18 14 2 2 $580,647 At 2 Years WON Summer Stakes, Coronation Futurity, Carleton Stakes, Remsen Stakes 2ND Vandal Stakes, Cup and Saucer Stakes At 3 Years WON Kentucky Derby, Flamingo Stakes, Florida Derby, Blue Grass Stakes, Preakness, Queen’s Plate 3RD Belmont Stakes Horse Eq. Wt. PP 1/4 1/2 3/4 MILE STR. FIN. Jockey Owner Odds To $1 Northern Dancer b 126 7 7 2-1/2 6 hd 6 2 1 hd 1 2 1 nk W. Hartack Windfields Farm 3.40 Hill Rise 126 11 6 1-1/2 7 2-1/2 8 hd 4 hd 2 1-1/2 2 3-1/4 W. Shoemaker El Peco Ranch 1.40 The Scoundrel b 126 6 3 1/2 4 hd 3 1 2 1 3 2 3 no M. Ycaza R. C. Ellsworth 6.00 Roman Brother 126 12 9 2 9 1/2 9 2 6 2 4 1/2 4 nk W. Chambers Harbor View Farm 30.60 Quadrangle b 126 2 5 1 5 1-1/2 4 hd 5 1-1/2 5 1 5 3 R. Ussery Rokeby Stables 5.30 Mr. Brick 126 1 2 3 1 1/2 1 1/2 3 1 6 3 6 3/4 I. -

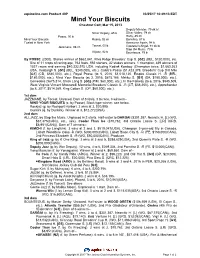

Mind Your Biscuits

equineline.com Product 40P 03/25/17 10:49:13 EDT Mind Your Biscuits Chestnut Colt; Mar 15, 2013 Deputy Minister, 79 dk b/ Silver Deputy, 85 b Silver Valley, 79 ch Posse, 00 b Rahy, 85 ch Mind Your Biscuits Raska, 92 ch Borishka, 87 b Foaled in New York Awesome Again, 94 b Toccet, 00 b Jazzmane, 06 ch Cozzene's Angel, 94 dk b/ Stop the Music, 70 b Alljazz, 92 b Bounteous, 79 b By POSSE (2000). Stakes winner of $662,841, Riva Ridge Breeders' Cup S. [G2] (BEL, $120,000), etc. Sire of 11 crops of racing age, 763 foals, 592 starters, 32 stakes winners, 1 champion, 439 winners of 1537 races and earning $40,332,975 USA, including Kodiak Kowboy (Champion twice, $1,663,363 USA, Vosburgh S. [G1] (BEL, $240,000), etc.), Caleb's Posse ($1,423,379, Breeders' Cup Dirt Mile [G1] (CD, $540,000), etc.), Royal Posse (to 5, 2016, $1,018,120, Empire Classic H. -R (BEL, $180,000), etc.), Mind Your Biscuits (at 3, 2016, $815,166, Malibu S. [G1] (SA, $180,000), etc.), Comedero ($675,814, Chick Lang S. [G3] (PIM, $60,000), etc.), In the Fairway (to 6, 2016, $545,509, West Virginia Vincent Moscarelli Memorial Breeders' Classic S. -R (CT, $38,250), etc.), Apprehender (to 8, 2017, $514,369, King Cotton S. (OP, $60,000), etc.). 1st dam JAZZMANE, by Toccet. Unraced. Dam of 5 foals, 3 to race, 3 winners-- MIND YOUR BISCUITS (c. by Posse). Black type winner, see below. Rockjaz (g. by Rockport Harbor). -

Philippa of Hainaut, Queen of England

THE UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS LIBRARY VMS Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2013 http://archive.org/details/philippaofhainauOOwhit PHILIPPA OF HAINAUT, QUEEN OF ENGLAND BY LEILA OLIVE WHITE A. B. Rockford College, 1914. THESIS Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS IN HISTORY IN THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS 1915 UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS THE GRADUATE SCHOOL ..%C+-7 ^ 19</ 1 HEREBY RECOMMEND THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION BY ftlil^ &&L^-^ J^B^L^T 0^ S^t ]J-CuJl^^-0<-^A- tjL_^jui^~ 6~^~~ ENTITLED ^Pt^^L^fifi f BE ACCEPTED AS FULFILLING THIS PART OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF CL^t* *~ In Charge of Major Work H ead of Department Recommendation concurred in: Committee on Final Examination CONTENTS Chapter I Philippa of Hainaut ---------------------- 1 Family and Birth Queen Isabella and Prince Edward at Valenciennes Marriage Arrangement -- Philippa in England The Wedding at York Coronation Philippa's Influence over Edward III -- Relations with the Papacy - - Her Popularity Hainauters in England. Chapter II Philippa and her Share in the Hundred Years' War ------- 15 English Alliances with Philippa's Relatives -- Emperor Louis -- Count of Hainaut Count of Juliers Vow of the Heron Philippa Goes to the Continent -- Stay at Antwerp -- Court at Louvain -- Philippa at Ghent Return to England Contest over the Hainaut Inherit- ance -- Battle of Neville's Cross -- Philippa at the Siege of Calais. Chapter III Philippa and her Court -------------------- 29 Brilliance of the English Court -- French Hostages King John of France Sir Engerraui de Coucy -- Dis- tinguished Visitors -- Foundation of the Round Table -- Amusements of the Court -- Tournaments -- Hunting The Black Death -- Extravagance of the Court -- Finan- cial Difficulties The Queen's Revenues -- Purveyance-- uiuc s Royal Manors « Philippa's Interest in the Clergy and in Religious Foundations — Hospital of St. -

Women in Geoffrey Chaucer's the Canterbury Tales: Woman As A

1 Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Vladislava Vaněčková Women in Geoffrey Chaucer's The Canterbury Tales: Woman as a Narrator, Woman in the Narrative Master's Diploma Thesis Supervisor: Doc. Milada Franková, Csc., M.A. 2007 2 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. ¼¼¼¼¼¼¼¼¼¼¼¼¼¼¼¼¼.. 3 Table of Contents 1. Introduction 4 2. Medieval Society 7 2.1 Chaucer in His Age 9 2.2 Chaucer's Pilgrims 11 3. Woman as a Narrator: the Voiced Silence of the Female Pilgrims 15 3.1 The Second Nun 20 3.2 The Prioress 27 3.3 The Wife of Bath 34 4. Woman in Male Narratives: theIdeal, the Satire, and Nothing in Between 50 4.1 The Knight's Tale, the Franklin's Tale: the Courtly Ideal 51 4.1.1 The Knight's Tale 52 4.1.2 The Franklin's Tale 56 4.2 The Man of Law's Tale, the Clerk's Tale: the Christian Ideal 64 4.2.1 The Man of Law's Tale 66 4.2.2 The Clerk's Tale 70 4.3 The Miller's Tale, the Shipman's Tale: No Ideal at All 78 4.3.1 The Miller's Tale 80 4.3.2 The Shipman's Tale 86 5. Conclusion 95 6. Works Cited and Consulted 100 4 1. Introduction Geoffrey Chaucer is a major influential figure in the history of English literature. His The Canterbury Tales are read and reshaped to suit its modern audiences. -

EDITED PEDIGREE for SASKIA's DREAM (GB)

EDITED PEDIGREE for SASKIA'S DREAM (GB) Green Desert (USA) Danzig (USA) Sire: (Bay 1983) Foreign Courier (USA) OASIS DREAM (GB) (Bay 2000) Hope (IRE) Dancing Brave (USA) SASKIA'S DREAM (GB) (Bay 1991) Bahamian (Bay mare 2008) Reprimand Mummy's Pet Dam: (Bay 1985) Just You Wait SWYNFORD PLEASURE (GB) (Bay 1996) Pleasuring (GB) Good Times (ITY) (Chesnut 1989) Gliding 4Sx5S Northern Dancer, 5Sx5S Never Bend, 5Sx5D Nearctic, 5Dx5D Tudor Minstrel SASKIA'S DREAM (GB), won 3 races (5f. - 7f.) from 3 to 5 years and £19,972 and placed 25 times. 1st Dam SWYNFORD PLEASURE (GB), won 9 races from 4 to 7 years and £83,474 and placed 38 times; Own sister to RASHBAG (GB) and SUGGESTIVE (GB); dam of 3 winners: SASKIA'S DREAM (GB), see above. BEE BRAVE (GB) (2010 f. by Rail Link (GB)), won 1 race at 2 years and £3,881; also won 2 races in U.S.A. at 4 years, 2014 and £73,227 and placed twice. PETSAS PLEASURE (GB) (2006 g. by Observatory (USA)), won 2 races at 3 and 5 years and £13,017 and placed 14 times. Warrendale (GB) (2011 f. by Three Valleys (USA)), placed twice at 2 years. Hidden Treasures (GB) (2013 f. by Zoffany (IRE)). She also has a yearling colt by Equiano (FR). 2nd Dam PLEASURING (GB), placed twice at 2 and 3 years; dam of 8 winners: SUGGESTIVE (GB) (g. by Reprimand), won 9 races from 3 to 8 years and £265,398 including Woodford Reserve Criterion Stakes, Newmarket, Gr.3, Bank of Scotland John of Gaunt Stakes, Haydock Park, L., Mcarthurglen City of York Stakes, York, L. -

The Significance of Anya Seton's Historical Fiction

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 5-2017 Breaking the cycle of silence : the significance of Anya Seton's historical fiction. Lindsey Marie Okoroafo (Jesnek) University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the American Literature Commons, American Popular Culture Commons, European History Commons, European Languages and Societies Commons, Gender and Sexuality Commons, Higher Education Commons, History of Gender Commons, Inequality and Stratification Commons, Language and Literacy Education Commons, Liberal Studies Commons, Literature in English, North America Commons, Modern Languages Commons, Modern Literature Commons, Other Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Political History Commons, Politics and Social Change Commons, Public History Commons, Quantitative, Qualitative, Comparative, and Historical Methodologies Commons, Reading and Language Commons, Secondary Education Commons, Social History Commons, Sociology of Culture Commons, United States History Commons, Women's History Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Okoroafo (Jesnek), Lindsey Marie, "Breaking the cycle of silence : the significance of Anya Seton's historical fiction." (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2676. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/2676 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional -

1930S Greats Horses/Jockeys

1930s Greats Horses/Jockeys Year Horse Gender Age Year Jockeys Rating Year Jockeys Rating 1933 Cavalcade Colt 2 1933 Arcaro, E. 1 1939 Adams, J. 2 1933 Bazaar Filly 2 1933 Bellizzi, D. 1 1939 Arcaro, E. 2 1933 Mata Hari Filly 2 1933 Coucci, S. 1 1939 Dupuy, H. 1 1933 Brokers Tip Colt 3 1933 Fisher, H. 0 1939 Fallon, L. 0 1933 Head Play Colt 3 1933 Gilbert, J. 2 1939 James, B. 3 1933 War Glory Colt 3 1933 Horvath, K. 0 1939 Longden, J. 3 1933 Barn Swallow Filly 3 1933 Humphries, L. 1 1939 Meade, D. 3 1933 Gallant Sir Colt 4 1933 Jones, R. 2 1939 Neves, R. 1 1933 Equipoise Horse 5 1933 Longden, J. 1 1939 Peters, M. 1 1933 Tambour Mare 5 1933 Meade, D. 1 1939 Richards, H. 1 1934 Balladier Colt 2 1933 Mills, H. 1 1939 Robertson, A. 1 1934 Chance Sun Colt 2 1933 Pollard, J. 1 1939 Ryan, P. 1 1934 Nellie Flag Filly 2 1933 Porter, E. 2 1939 Seabo, G. 1 1934 Cavalcade Colt 3 1933 Robertson, A. 1 1939 Smith, F. A. 2 1934 Discovery Colt 3 1933 Saunders, W. 1 1939 Smith, G. 1 1934 Bazaar Filly 3 1933 Simmons, H. 1 1939 Stout, J. 1 1934 Mata Hari Filly 3 1933 Smith, J. 1 1939 Taylor, W. L. 1 1934 Advising Anna Filly 4 1933 Westrope, J. 4 1939 Wall, N. 1 1934 Faireno Horse 5 1933 Woolf, G. 1 1939 Westrope, J. 1 1934 Equipoise Horse 6 1933 Workman, R. -

History of the Plantagenet Kings of England [email protected]

History of the Plantagenet Kings of England [email protected] http://newsummer.com/presentations/Plantagenet Introduction Plantagenet: Pronunciation & Usage Salic Law: "of Salic land no portion of the inheritance shall come to a woman: but the whole inheritance of the land shall come to the male sex." Primogeniture: inheritance moves from eldest son to youngest, with variations Shakespeare's Plantagenet plays The Life and Death of King John Edward III (probably wrote part of it) Richard II Henry IV, Part 1 Henry IV, Part 2 Henry V Henry VI, Part 1 Henry VI, Part 2 Henry VI, Part 3 Richard III Brief assessments The greatest among them: Henry II, Edward I, Edward III The unfulfilled: Richard I, Henry V The worst: John, Edward II, Richard II, Richard III The tragic: Henry VI The Queens Matilda of Scotland, c10801118 (Henry I) Empress Matilda, 11021167 (Geoffrey Plantagent) Eleanor of Aquitaine, c11221204 (Henry II) Isabella of France, c12951348 (Edward II) Margaret of Anjou, 14301482 (Henry VI) Other key notables Richard de Clare "Strongbow," 11301176 William the Marshal, 1st Earl of Pembroke, 11471219 Simon de Montfort, 6th Earl of Leicester, c12081265 Roger Mortimer, Earl of March, 12871330 Henry "Hotspur" Percy, 13641403 Richard Neville "The Kingmaker," 14281471 Some of the important Battles Hastings (Wm I, 1066): Conquest Lincoln (Stephen, 1141): King Stephen captured Arsuf (Richard I, 1191): Richard defeats Salidin Bouvines (John, 1214): Normandy lost to the French Lincoln, 2nd (Henry III, 1217): Pembroke defeats -

Open Finalthesis Weber Pdf.Pdf

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY AND RELIGIOUS STUDIES FRACTURED POLITICS: DIPLOMACY, MARRIAGE, AND THE LAST PHASE OF THE HUNDRED YEARS WAR ARIEL WEBER SPRING 2014 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a baccalaureate degree in Medieval Studies with honors in Medieval Studies Reviewed and approved* by the following: Benjamin T. Hudson Professor of History and Medieval Studies Thesis Supervisor/Honors Adviser Robert Edwards Professor of English and Comparative Literature Thesis Reader * Signatures are on file in the Schreyer Honors College. i ABSTRACT The beginning of the Hundred Years War came about from relentless conflict between France and England, with roots that can be traced the whole way to the 11th century, following the Norman invasion of England. These periods of engagement were the result of English nobles both living in and possessing land in northwest France. In their efforts to prevent further bloodshed, the monarchs began to engage in marriage diplomacy; by sending a young princess to a rival country, the hope would be that her native people would be unwilling to wage war on a royal family that carried their own blood. While this method temporarily succeeded, the tradition would create serious issues of inheritance, and the beginning of the last phase of the Hundred Years War, and the last act of success on the part of the English, the Treaty of Troyes, is the culmination of the efforts of the French kings of the early 14th century to pacify their English neighbors, cousins, and nephews. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter 1 Plantagenet Claim to France................................................................................... -

Major Events, People and Books of the 14Th Century Doug Strong

Major Events, People and Books of the 14th Century Doug Strong A time line of major events of the 14th century 1272: Coronation of Edward I. July 7th, 1307: Death of Edward I. 1307: Coronation of Edward II. 1308: Wedding of Isabella of France to Edward II. June 19th, 1312: The murder of Piers Gaveston. 1314: Battle of Bannockburn. 1321: The death of Dante. 1326: The executions of Hugh Despenser and Hugh Despenser the younger. September, 1327: Murder of Edward II. February 1st, 1327: Coronation of Edward III. 1337: Beginning of Hundred years war. 1346: Battle of Crecy. October, 1347-1353: The Black Death (England, late 1348-1353). April 23rd, 1350: Foundation of the order of the Garter. Circa 1350: Boccaccio wrote the Decameron . 1356: The battle of Potiers. 1362: Langland released the first version of Piers Plowman . July 18th, 1374: Petrarch died. 1375: The death of Boccaccio. June 8th, 1376: Death of Edward the Black Prince. June 21st, 1377: Death of Edward III. 1377: Coronation of Richard II. 1378-1417: The Papal Schism. 1379-1382: The rise of John Wycliffe and the Lollard Heresy. June 7th, 1381: The great English peasant revolt. 1386: Geoffrey Chaucer began The Canterbury Tales . August 8th, 1388: The battle of Otterburn. Circa 1390 : Forme of Cury was written. 1393: The Goodman Of Paris was written. Summer, 1399: The deposition of Richard II. October 13, 1399: Coronation of Henry IV. February, 1400: The Death of Richard II. 1400: The death of Chaucer. A list of important figures of the age: Geoffrey Chaucer (England) Richard II (England)