Tongues of Their Mothers: the Language of Writing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Symposium Supported by NIHSS Dear Participant Who Was Can Themba?

Symposium supported by NIHSS Dear Participant Who was Can Themba? The Can Themba Symposium is the first of its kind. It celebrates According to Stan Motjuwadi, the House of Truth was “Can’s way Daniel Canodoce Themba (Can Themba) was born on 21 June 1924, in Marabastad, Pretoria. He studied at the University of Fort Hare the life of Daniel Canadoce (Can) Themba—a distinguished South of cocking a snook at snobbery, officialdom and anything that from 1945-1947, graduating his BA degree with a distinction in English. He taught at various schools in Johannesburg and in 1953 he joined African writer, journalist and teacher on the 51st anniversary of his smacked of the formal. Everybody but a snob was welcome at the Drum magazine as a reporter and later became the associate editor. He left Drum in 1959 and in the early 1960s he went into exile in passing. Themba was born in Marabastad, Pretoria, on 21 June 1924, House of Truth.” Swaziland. He was declared a statutory communist by the apartheid government and his works could neither be published nor quoted in and died in Swaziland on 8 September 1967, at just 43years old. South Africa. He died of coronary thrombosis on 8 September 1967. It is against this backdrop that I penned the first Can Themba Although he passed away without a single book under his authorship, bioplay and titled it The House of Truth, thus revealing a new way of his works have outlived him and he remains one of the most perceiving his complex world from the inside. -

Acclaimed Director Peter Brook Talks About the Suit, Playing This Week at OZ

May 22, 2014 By Martin Brady Acclaimed director Peter Brook talks about The Suit, playing this week at OZ Billed as "a destination for innovative contemporary art experiences," OZ Nashville has not disappointed in its inaugural season. The alternative venue — a renovated cigar warehouse — offers high-style ambience and hosts performances and installations across all artistic disciplines. OZ's first presentation for the garden-variety theatergoer, The Suit, debuts this week, though there's very little that's ordinary about the piece, which is concluding an ambitious two-year international tour in Music City. The Suit has been acclaimed across the globe, and has received raves from critics in New York, San Francisco and Los Angeles. Based on the late South African writer Can Themba's powerful novella, the play centers on Philomen, a middle-class black lawyer in apartheid-era South Africa who catches his wife, Matilda, having an affair. In haste, her lover leaves behind his clothes, and as her punishment, Philemon makes Matilda treat her lover's suit as an honored houseguest, even to the point of including it at the dinner table or taking it out for walks. Making this singular event even more noteworthy, it's under the direction of Peter Brook, a world giant of theatrical innovation. "First of all, in the thousands of plays and novels about marital betrayal, you'll find something amazing, but The Suit presents a new situation that happens with a different combination of ingredients," says Brook, speaking by phone from Paris, where he creates for the stage under the aegis of his company, Thèâtre des Bouffes du Nord. -

CAP UCLA Presents Peter Brook's 'The Suit'

Media Alert Monday March 10, 2014 Contact: Jessica Wolf 310.825.7789 [email protected] CAP UCLA Presents Peter Brook’s ‘The Suit’ April 9-19 Eight performances at UCLA’s Freud Playhouse Center for the Art of Performance at UCLA presents “The Suit,” a simmering tale of betrayal and resentment set in the politically charged sphere of apartheid-era South Africa, performed by Théâtre des Bouffes du Nord, with direction, adaptation and musical direction by Peter Brook, Marie-Hélène Estienne and Franck Krawczyk. Performances run April 9-19, 2014 and tickets ($30-$65) are available cap.ucla.edu , Ticketmaster or the UCLA Central Ticket Office (310.825.2101). The story of “The Suit” centers on Philomen, a middle-class lawyer and his wife, Matilda. The suit of the title belongs to Matilda’s lover and is left behind when Philomen catches the illicit couple together. As punishment, Philomen makes Matilda treat the suit as an honored guest as a constant reminder of her adultery. The setting of Sophiatown, a teeming township that was erased shortly after Can Themba wrote his novel, is as much a character in the play as the unfortunate couple, and this production lends it life and energy with a minimal cast. Themba was a South African writer during apartheid. His short novel, “The Suit” was supposed to change the writer’s life, but the cruel restrictions in his native country led him to exile, his works banned in his home country. He died an alcoholic before his most famous work was adapted for the stage by Mothobi Mutloatse and Barney Simon at Johannesburg’s Market Theatre in the newly liberated South Africa of the 1990s. -

A Weekly Supplement of the Market Theatre Foundation

26 JUN - 2 JUL BUZZA weekly supplement of the Market Theatre Foundation Images from the production HANI THE MARKET THEATRE REMEMBERS CHRIS HANI Through hip-hop, rap, ballad and contemporary production devised commander was assassinated on high-powered energetic dances and directed by Leila Henriques is 10 April 1993 outside his home in the students from the Market inspired by the hit American Dawn Park, Boksburg. Theatre Laboratory are preparing musical Hamilton. to present their production, Hani, The Market Theatre Laboratory at the National Arts Festival in The staging of Hani at the National production reflects on the political Grahamstown. Arts Festival coincides with the and personal life of Chris Hani 75th anniversary of the birth of through the eyes of a post-1994 Amidst the current political the charismatic leader. He was generation. challenges in South Africa, Hani born on 28 June 1942. The unsung is an inspiring story about the life hero who was the South African For details about Hani at the and times of the assassinated Communist Party (SACP) general National Arts Festival please see political leader, Chris Hani. The secretary and Mkhonto We Sizwe page 12. Images sourced from the internet Images sourced from the internet 2 3 LESEDI JOB ANNOUNCED AS 2017 SOPHIE MGCINA EMERGING VOICE AWARD WINNER Rising star actress and theatre in Fisher’s of Hope at the Baxter imagining the solo work as an director Lesedi Job was named Theatre, Ketekang at the Market ensemble piece. During April, she the winner of the Market Theatre Theatre and Curl Up & Dye at the was invited to participate at the Foundation’s 4th annual Sophie Auto & General Theatre. -

The-Suit-Nashville-P

May 16, 2014 By Cass Teague OZ presents The Suit A phenomenally engaging drama is being staged in Nashville’s new prime venue for contemporary arts. A heart-rending exploration of marriage and survival in apartheid South Africa is coming to OZ, Thursday, May 22 through Sunday, May 24. Based on The Suit by Can Themba, the show utilizes three actors and three musicians to tell the story. The Suit focuses on Philomen, a middle-class lawyer, who catches his wife Matilda in the midst of an affair. Her lover flees, leaving behind the eponymous garment of the play’s title. As punishment, Philemon makes Matilda treat the suit as an honored guest, preparing meals for it, entertaining it and taking it out for walks as a constant reminder of her adultery. The LA Times review proclaims “every actor moves like a dancer. Every actor speaks like a singer. And song pervades all. Pianist and accordionist, trumpet play and guitarist underscore the production with arrangements of Schubert songs, South African songs, African American blues, ‘The Blue Danube’ and Bach.” Directed and adapted by one of Europe’s most respected and visionary theatre and film directors, Peter Brook, and his long-term collaborators Marie- Hélène Estienne and Franck Krawczyk, The Suit is a music-filled and poignant tale of marital betrayal and resentment with an intimate glimpse of life in apartheid-era South Africa. Written by South African novelist Can Themba, this exquisite work, created in the Paris-based Théâtre des Bouffes du Nord, features innovative staging that integrates live musicians among actors. -

The Suit by Can Themba, Mothobi Mutloatse, and Barney Simon

BAM 2013 Winter/Spring Brooklyn Academy of Music Théâtre des Bouffes du Nord Alan H. Fishman, Chairman of the Board William I. Campbell, The Vice Chairman of the Board Adam E. Max, Vice Chairman of the Board Karen Brooks Hopkins, President Joseph V. Melillo, Executive Producer Suit BAM Harvey Theater Jan 17—19, 22, 23, 25, 26, 29—31; Feb 1 & 2 at 7:30pm Jan 24 at 8pm (Gala) Jan 19, 26 & Feb 2 at 2pm Jan 20 & 27 at 3pm Approximate running time: 75 minutes, no intermission Based on The Suit by Can Themba, Mothobi Mutloatse, and Barney Simon Direction, adaptation, and music by Peter Brook, Marie-Hélène Estienne, and Franck Krawczyk Lighting design by Philippe Vialatte Scenic elements and costume design by Oria Puppo BAM 2013 Winter/Spring sponsor: Assistant director Rikki Henry (also onstage) With Nonhlanhla Kheswa BAM 2013 Theater Sponsor Jared McNeill William Nadylam Major support for theater at BAM: The Gladys Krieble Delmas Foundation Musicians Stephanie & Timothy Ingrassia Arthur Astier guitar Donald R. Mullen, Jr. The Fan Fox & Leslie R. Samuels Foundation, Inc. Raphaël Chambouvet piano Harvey Schwartz & Annie Hubbard David Dupuis trumpet The Morris and Alma Schapiro Fund The SHS Foundation American stage manager R. Michael Blanco The Shubert Foundation, Inc. French stage manager Thomas Becelewski Rikki Henry & Nonhlanhla Kheswa Photo: Pascal Gely South African writer Can Themba’s novel, The Suit, was supposed to change the writer’s life. Tragical- ly, the cruel restrictions of apartheid in his native country meant that his life changed in a completely different way. He went into exile in Swaziland, his works banned in South Africa. -

Grade 12 Dramatic Arts Self Study Material 2020

DRAMATIC ARTS GRADE 12 SELF STUDY MATERIAL-2020 THIS RESOURCE PACK BELONGS TO NAME: _____________________________________ 1 | Page Dramatic Arts Self- Study Resource Pack Grade 12 Dear Grade 12 learner This self-study resource pack is compiled to enable you to continue your studies while you are away from classroom contact sessions. If you work through the pack diligently, it will equip you with the relevant knowledge to prepare for the year ahead. There is curriculum content as well as past papers which I hope will be of benefit to your individual need. Best wishes for the year ahead. Dr P Gramanie 2 | Page Dramatic Arts Self- Study Resource Pack Grade 12 TERM 2 Topic 5: Prescribed Play Text 2: South African Text (1960 -1994) SOPHIATOWN by JUNCTION AVENUE THEATRE COMPANY Background/context: social, political, religious, economic, artistic, historical, theatrical, as relevant to chosen play text Background of the playwright / script developers Principles of Drama in chosen play text such as: plot, dialogue, character, theme Style / genre of play text Staging/setting Techniques and conventions Audience reception and critical response (by original audience and today 3 | Page Dramatic Arts Self- Study Resource Pack Grade 12 SOPHIATOWN by JUNCTION AVENUE THEATRE COMPANY “The city that was within a city, the Gay Paris of Johannesburg, the notorious Casbah gang den, the shebeeniest of them all.” Background and context of Sophiatown Social Sophiatown was a suburb in Johannesburg and is also known as Kofifi or Softown. Sophiatown was different from other South African townships and was the only freehold township at the time which meant that black residents could purchase and own land. -

Brook, by the Late Sixties a Thinker As Well As a Practitioner of Theatre, Pushed Further, Led by a Strong Metaphysical Drive to See Beyond the Surface of Things

Excerpted from Peter Brook: A Biography by Michael Kustow. Copyright © by the author. To be published by St. Martin's Press in March 2005. From chapter 11, "To Paris and Beyond: 1970–73," 198–204. Brook, by the late sixties a thinker as well as a practitioner of theatre, pushed further, led by a strong metaphysical drive to see beyond the surface of things. Although the Royal Court 'revolution' had brought a new social realism and sense of debate into the British theatre, for Brook it still operated on too narrow a waveband. The Elizabethan theatre, wrote Brook, 'was far ahead of our present theatre, which can only be acutely partisan or weakly liberal. Furthermore, the Elizabethan theatre passed from the world of action to the world of thought, from down-to-earth reality to the extreme of metaphysical inquiry without effort and without self-consciousness. Here again, it is far ahead of our own theatre which has the vitality to deal with life but not the courage to deal with life-and- death.' In 1970, he faced the fact that he'd had enough of his love-hate relationship with the English-speaking theatre. Taking further the diverse group of actors in the Roundhouse Tempest company, which had been his first experience of working with a group not defined by its nationality, he began to lay plans for an international group. To begin with, he wanted to work free from box-office pressures; he needed funds to subsidise the freedom to perform to audiences only as and when the work needed it. -

Théâtre Des Bouffes Du Nord: the Suit LOS ANGELES PREMIERE

Théâtre des Bouffes du Nord: The Suit LOS ANGELES PREMIERE Wed, Apr 9 at 8pm Based on The Suit by Can Themba, Mothobi Mutloatse and Barney Simon. Thu, Apr 10 at 8pm Direction, adaptation and musical direction by Fri, Apr 11 at 8pm Peter Brook, Marie-Hélène Estienne and Franck Krawczyk Sat, Apr 12 at 2pm & 8pm Sun, Apr 13 at 2pm Lighting by Philippe Vialatte Thu, Apr 17 at 8pm Costumes by Oria Puppo Assistant director: Rikki Henry Fri, Apr 18 at 8pm Sat, Apr 19 at 8pm With Jordan Barbour, Ivanno Jeremiah, Nonhlanhla Kheswa Freud Playhouse at Macgowan Hall Musicians Arthur Astier (guitar), Mark Christine (piano), Mark Kavuma (trumpet) PERFORMANCE DURATION: 75 minutes; No intermission Production Manager/Lighting Manager Pascal Baxter Company Manager/Stage Manager: Thomas Becelewski Supported in part by the Merle & Peter Mullin Endowment for the Performing Première in Paris at Théâtre des Bouffes du Nord on 3rd April 2012 Arts, the Shirley & Ralph Shapiro Director’s On tour during the 2012/2013 and 2013/2014 seasons Discretionary Fund with additional support by Diane Levine and Robert Wass and the Production : C.I.C.T. / Théâtre des Bouffes du Nord Center for Global Management at the UCLA Coproduction: Fondazione Campania dei Festival / Napoli Teatro Festival Italia, Les Théâtres Anderson School of Management de la Ville de Luxembourg, Young Vic Theatre, Théâtre de la Place – Liège With the support of the C.I.R.T. MEDIA SPONSOR: MESSAGE FROM THE CENTER: Stories are important. Storytelling is a driving force in the ethos of the art of performance. -

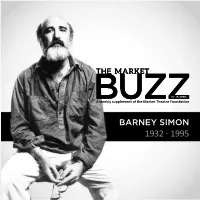

Barney Simon 1932 - 1995 Remembering Barney Simon

1013 - - 16 19 AP MARRIL BARNEY SIMON 1932 - 1995 REMEMBERING BARNEY SIMON The Market Theatre’s first Artistic passed away in June 1995. He of the Market’s theatre complex, Director and one of South Africa’s was celebrated for his method of where aspirant playwrights could most courageous and innovative creating and developing original develop and stage their plays under playwrights and directors, Barney plays through a workshop process his superbly creative guidance.” Simon, firmly believed that culture of field research, improvisation could change society. Barney and collaborative writing, Barney, admired by his peers and Simon co-founded the Market sometimes with untrained actors a role model for younger theatre Theatre with Mannie Manim in or combinations of musicians, makers, would have turned 1974. The Market Theatre became professional actors and people 85 on 13 April 2017. In 2015 known as the ‘home of protest entirely new to the theatre. Artistic Director, James Ngcobo, theatre’, one of the few spaces that remembered Barney Simon’s practiced non-racialism. In a moving obituary Nadine legacy by reviving one of Barney’s Gordimer wrote for the classic plays called Cincinnati: Working under the racial Independent newspaper in July Scenes From the City Life directed segregation laws of apartheid 1995, “Simon was artistic director by Clive Mathibe. Clive Mathibe without state subsidies and under of the Market Theatre for virtually was mentored by one of Barney constant threat of arrest for staging all his life, producing his own Simon’s esteemed colleagues and controversial contemporary plays plays, international works, and longtime friend, Vanessa Cook. -

See Page 5 for More Information

6 - 12 MAR SEE PAGE 5 FOR MORE INFORMATION 1 40 COUNTRIES AT THE MARKET THEATRE SOUTH AFRICAN FILM FESTIVAL VENUE Now in its second year, Rapid The Festival features films of Market Theatre Lion also known as The multiple genres and varying DATES South African International lengths, Q&A sessions, and 5 - 12 March 2017 Film Festival celebrates the niche sections. These include TIME magnitude of BRICS and African Kindercinema aimed at the Check out Screenings & Times filmmaking with a special youngest filmgoers and their here: emphasis on South African parents; The Heritage platform, www.rapidlion.co.za cinema. The Film Festival aims which features South African to be one of the most-loved and films of yesteryear; and important cultural events on the Homage, comprising the work Johannesburg calendar. of the recipient of The Lionel Ngakane Lifetime Achievement From 5 March to 12 March Award.From start to finish it is Rapid Lion 2017 will bring 140 a compelling story as these two films from 40 countries to The men who described as part of Market Theatre in Newtown, the continuum of struggle show Johannesburg. their cards and slowly unleash and display their power for each other. 2 3 SOPHIATOWN ITSOSENG A TALE ABOUT TRIUMPH! VENUE ‘Molusi is a charismatic performer Ramolao Makhene with a natural humor that keeps VENUE The play is a life history of the mid- DATES the piece from being too heavy. John Kani 1950s township, Sophiatown, in 7 April - 7 May 2017 The language of the play is a mix DATES west central Johannesburg, South of blunt observation and poetic TIME 31 March - 14 May 2017 Africa; one of the only places at embellishment that shows Molusi that time where black people could Tue - Sat 20:15 TIME is a talented playwright that can own property. -

Théâtre Des Bouffes Du Nord

UMS PRESENTS THE SUIT A production of Théâtre des Bouffes du Nord Based on The Suit by Can Themba, Mothobi Mutloatse, and Barney Simon Direction, adaptation, and musical direction by Peter Brook, Marie-Hélène Estienne, and Franck Krawczyk Wednesday Evening, February 19, 2014 at 7:30 Thursday Evening, February 20, 2014 at 7:30 Friday Evening, February 21, 2014 at 8:00 Saturday Evening, February 22, 2014 at 8:00 Power Center • Ann Arbor 53rd, 54th, 55th, and 56th Performances of the 135th Annual Season International Theater Series Photo: The Suit; photographer: Johan Persson. 19 UMS CREATIVE TEAM Direction, adaptation, and musical direction by Peter Brook, Marie-Hélène Estienne, and Franck Krawczyk Lighting Design Philippe Vialatte Costume Design Oria Puppo Assistant Director Rikki Henry PROGRAM A co-production between Fondazione Campania dei Festival / Napoli Teatro Festival Italia, Les Théâtres de la Ville de Luxembourg, Young Vic Theatre, Théâtre de la Place — Liège The Suit is approximately 75 minutes in duration and is performed without intermission. WINTER 2014 Following Wednesday evening’s performance, please feel free to remain in your seats and join us for a post-performance Q&A with members of the company. Funded in part by a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts. Media partnership provided by WDET 101.9 FM, Michigan Radio 91.7 FM, and Between the Lines. Special thanks to Naomi Andre, Clare Croft, Amy Chavasse, Larry La Fountain-Stokes, Priscilla Lindsay, Gillian Eaton, Anita Gonzalez, Rob Najarian, the U-M Theatre Department, and Daniel Herwitz, for their support of and participation in events surrounding these performances by Théâtre des Bouffes du Nord.