In Sickness and in Death: Assessing Frailty in Human Skeletal Remains

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alaris Capture Pro Software

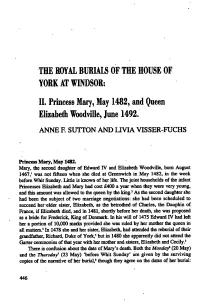

THE ROYAL BURIALS OF THE HOUSE OF YORKAT WINDSOR. II. Princess Mary,May 1482, and Queen Elizabeth Woodville,June 1492.- ANNE F. SUTTON AND LIVIA VISSER—FUCHS Princess Mary, May 1482. Mary, the second daughter of Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville, born August 1467, ' was not fifteen when she died at Greenwich' 1n May 1482, in the week before Whit Sunday. Little is known of be; life. The joint households of the infant Princesses Elizabeth and Mary had cost £400 a year when they were very young, and this amount was allowed to the queen by the king} As the second daughter she had been the subject of two marriage negotiations: she had been scheduled to succeed her-elder sister, Elizabeth, as the betrothed of Charles, the Dauphin of France, if Elizabeth died, and in 1481, shortly before her death, she was proposed as a bride for Frederick, King of Denmark. In his will of 1475 Edward IV had left her a portion of 10,000 marks provided she was ruled by her mother the queen in all matters.1 In 1478 she and her sister, Elizabeth, had attended the reburial of their grandfather, Richard, Duke of York,“ but in 1480 she apparently did not attend the Garter ceremonies of that year with her mother and sisters, Elizabeth and Cecily.’ There is confusion about the date of Mary’s death. Both the'Monday“ (20 May) and the Thursday’ (23 May) ‘before Whit Sunday’ are given by the surviving copies of the narrative of her burial,“ though they agree on the dates of her burial: 446 the Monday and Tuesday in Whitsun Week, 27-28 May.9 Edward IV was at Canterbury on 17 May, and back in London on 23 May, and may have seen his dying daughter between those dates. -

English Monks Suppression of the Monasteries

ENGLISH MONKS and the SUPPRESSION OF THE MONASTERIES ENGLISH MONKS and the SUPPRESSION OF THE MONASTERIES by GEOFFREY BAS KER VILLE M.A. (I) JONA THAN CAPE THIRTY BEDFORD SQUARE LONDON FIRST PUBLISHED I937 JONATHAN CAPE LTD. JO BEDFORD SQUARE, LONDON AND 91 WELLINGTON STREET WEST, TORONTO PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN IN THE CITY OF OXFORD AT THE ALDEN PRESS PAPER MADE BY JOHN DICKINSON & CO. LTD. BOUND BY A. W. BAIN & CO. LTD. CONTENTS PREFACE 7 INTRODUCTION 9 I MONASTIC DUTIES AND ACTIVITIES I 9 II LAY INTERFERENCE IN MONASTIC AFFAIRS 45 III ECCLESIASTICAL INTERFERENCE IN MONASTIC AFFAIRS 72 IV PRECEDENTS FOR SUPPRESSION I 308- I 534 96 V THE ROYAL VISITATION OF THE MONASTERIES 1535 120 VI SUPPRESSION OF THE SMALLER MONASTERIES AND THE PILGRIMAGE OF GRACE 1536-1537 144 VII FROM THE PILGRIMAGE OF GRACE TO THE FINAL SUPPRESSION 153 7- I 540 169 VIII NUNS 205 IX THE FRIARS 2 2 7 X THE FATE OF THE DISPOSSESSED RELIGIOUS 246 EPILOGUE 273 APPENDIX 293 INDEX 301 5 PREFACE THE four hundredth anniversary of the suppression of the English monasteries would seem a fit occasion on which to attempt a summary of the latest views on a thorny subject. This book cannot be expected to please everybody, and it makes no attempt to conciliate those who prefer sentiment to truth, or who allow their reading of historical events to be distorted by present-day controversies, whether ecclesiastical or political. In that respect it tries to live up to the dictum of Samuel Butler that 'he excels most who hits the golden mean most exactly in the middle'. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Preparatory to Anglo-Saxon England Being the Collected Papers of Frank Merry Stenton by F.M

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Preparatory to Anglo-Saxon England Being the Collected Papers of Frank Merry Stenton by F.M. Stenton Preparatory to Anglo-Saxon England: Being the Collected Papers of Frank Merry Stenton by F.M. Stenton. Our systems have detected unusual traffic activity from your network. Please complete this reCAPTCHA to demonstrate that it's you making the requests and not a robot. If you are having trouble seeing or completing this challenge, this page may help. If you continue to experience issues, you can contact JSTOR support. Block Reference: #c8fec890-ce23-11eb-8350-515676f23684 VID: #(null) IP: 116.202.236.252 Date and time: Tue, 15 Jun 2021 21:51:05 GMT. Preparatory to Anglo-Saxon England: Being the Collected Papers of Frank Merry Stenton by F.M. Stenton. Our systems have detected unusual traffic activity from your network. Please complete this reCAPTCHA to demonstrate that it's you making the requests and not a robot. If you are having trouble seeing or completing this challenge, this page may help. If you continue to experience issues, you can contact JSTOR support. Block Reference: #c91a18c0-ce23-11eb-9d99-5b572480f815 VID: #(null) IP: 116.202.236.252 Date and time: Tue, 15 Jun 2021 21:51:05 GMT. Abbot of Peterborough. Abbot , meaning father, is an ecclesiastical title given to the male head of a monastery in various traditions, including Christianity. The office may also be given as an honorary title to a clergyman who is not the head of a monastery. The female equivalent is abbess. An abbey is a complex of buildings used by members of a religious order under the governance of an abbot or abbess. -

REBIRTH, REFORM and RESILIENCE Universities in Transition 1300-1700

REBIRTH, REFORM AND RESILIENCE Universities in Transition 1300-1700 Edited by James M. Kittelson and Pamela J. Transue $25.00 REBIRTH, REFORM, AND RESILIENCE Universities in Transition, 1300-1700 Edited by James M. Kittelson and Pamela]. Transue In his Introduction to this collection of original essays, Professor Kittelson notes that the university is one of the few institutions that medieval Latin Christendom contributed directly to modern Western civilization. An export wherever else it is found, it is unique to Western culture. All cultures, to be sure, have had their intellec tuals—those men and women whose task it has been to learn, to know, and to teach. But only in Latin Christendom were scholars—the company of masters and students—found gathered together into the universitas whose entire purpose was to develop and disseminate knowledge in a continu ous and systematic fashion with little regard for the consequences of their activities. The studies in this volume treat the history of the universities from the late Middle Ages through the Reformation; that is, from the time of their secure founding, through the period in which they were posed the challenges of humanism and con fessionalism, but before the explosion of knowl edge that marked the emergence of modern science and the advent of the Enlightenment. The essays and their authors are: "University and Society on the Threshold of Modern Times: The German Connection," by Heiko A. Ober man; "The Importance of the Reformation for the Universities: Culture and Confessions in the Criti cal Years," by Lewis W. Spitz; "Science and the Medieval University," by Edward Grant; "The Role of English Thought in the Transformation of University Education in the Late Middle Ages," by William J. -

Frail Or Hale: Skeletal Frailty Indices in Medieval London Skeletons

RESEARCH ARTICLE Frail or hale: Skeletal frailty indices in Medieval London skeletons Kathryn E. Marklein1*, Douglas E. Crews1,2 1 Department of Anthropology, Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio, United States of America, 2 College of Public Health, Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio, United States of America * [email protected] Abstract a1111111111 a1111111111 To broaden bioarchaeological applicability of skeletal frailty indices (SFIs) and increase a1111111111 sample size, we propose indices with fewer biomarkers (2±11 non-metric biomarkers) and a1111111111 a1111111111 compare these reduced biomarker SFIs to the original metric/non-metric 13-biomarker SFI. From the 2-11-biomarker SFIs, we choose the index with the fewest biomarkers (6- biomarker SFI), which still maintains the statistical robusticity of a 13-biomarker SFI, and apply this index to the same Medieval monastic and nonmonastic populations, albeit with an increased sample size. For this increased monastic and nonmonastic sample, we also pro- OPEN ACCESS pose and implement a 4-biomarker SFI, comprised of biomarkers from each of four stressor Citation: Marklein KE, Crews DE (2017) Frail or categories, and compare these SFI distributions with those of the non-metric biomarker hale: Skeletal frailty indices in Medieval London skeletons. PLoS ONE 12(5): e0176025. https://doi. SFIs. From the Museum of London WORD database, we tabulate multiple SFIs (2- to 13- org/10.1371/journal.pone.0176025 biomarkers) for Medieval monastic and nonmonastic samples (N = 134). We evaluate asso- Editor: Luca Bondioli, Museo delle Civiltà, ITALY ciations between these ten non-metric SFIs and the 13-biomarker SFI using Spearman's correlation coefficients. -

Where's Wocca?

WHERE’S WOCCA? Iain Wakeford © 2014 Somewhere in Old Woking, presumably on or near the site of St Peter’s Church, was the original Saxon monastery of Wocchingas. ast week I wrote about the possible first question of whether ‘ingas’ place-names were some that originally both Godley and Woking ever record of the name Woking (or amongst the earliest of Saxon settlements is Hundred’s were one (the land of the L Wocchingas) dating from between 708- still very much up in the air. To the south at Wocchingas tribe perhaps). Just because the 715 AD, and the slightly earlier (but some some stage were the Godalmingas, with the possibly oldest surviving record for Chertsey might say slightly more dubious) record of Basingas to the west, the Sunningas to the Abbey is about thirty years older than the Chertsey Abbey from 673-75 AD. But even if north and beyond them the Readingas further possibly earliest surviving record of Woking’s both records were authentic documents and not up the Thames Valley. Monastery, doesn’t mean that Chertsey is older 11th or 12th century copies or forgeries, they are than Woking – although that is the way that In Surrey the lands of the Godalmingas and not necessarily the first time that either Woking most historian choose to interpret it! or Chertsey were recorded. It is unlikely that any Woccingas became in later Saxon times the more ancient documents will suddenly show up names of administrative areas known as The problem is that there is also very little now, but who can tell how many older ‘Hundreds’ (more of which on later pages), but archaeological evidence to support or refute the documents have been lost and who knows in our area there was another Hundred, based ‘ancient’ records. -

Cartularies, See Medieval Cartularies of Great Britain: Amendments And

MONASTIC RESEARCH BULLETIN Consolidated index of articles and subjects A A Biographical Register of the English Cathedral priories of the Province of Canterbury, MRB1, p.18; MRB3, p.43 A Lost Letter of Peter of Celle, MRB 13 p.1 A Monastic History of Wales, MRB12, p.38 A New International Research Centre for the Comparative History of Religious Orders in Eichstatt (Germany), MRB13, p.21 A New Project at Strata Florida, Ceredigion, Wales, MRB13, p.13 A Register of the Durham Monks, MRB1, p.16 Addenda and Corrigenda to David Knowles and R. Neville Hadcock, Medieval Religious Houses, England and Wales, MRB6, p.1 AELRED OF RIEVAULX, see Walter Daniel’s Life of Aelred of Rievaulx Re‐ Considered, MRB13, p.34 ALVINGHAM PRIORY, see Cartulary of Alvingham Priory, MRB9, p.21 Apostolic poverty at the ends of the earth: the Observant Franciscans in Scotland, c.1450‐1560, MRB11, p.39 ARCHAEOLOGY, see Medieval Art, Architecture, Archaeology and Economy and Bury St Edmunds, MRB3, p.45; The Archaeology of Later Monastic Hospitality, MRB3 p.51; The Patronage of Benedictine Art and Architecture in the West of England during the later middle ages (1340‐1540), MRB8 p.34 ART, see Medieval Art, Architecture, Archaeology and Economy and Bury St Edmunds, MRB3, p.45; Monastic Wall Painting in England, MRB5 p.32; The Patronage of Benedictine Art and Architecture in the West of England during the later middle ages (1340‐1540), MRB8 p.34; Judgement in medieval monastic art, MRB11, p.46. ATHELNEY ABBEY, see The Cartulary of Athelney Abbey rediscovered Augustinians -

English Congregation

CONTAINING THE JRise, <25rotDtf), anD Present ^tate of tfie ENGLISH CONGREGATION OF THE #rXrer uf ^t* Umtttitt, DRAWN FROM THE ARCHIVES OF THE HOUSES OF THE SAID CON GREGATION AT DOUAY IN FLANDERS, DIEULWART IN LORRAINE, PARIS IN FRANCE, AND LAMBSPRING IN GERMANY, WHERE ARE PRESERVED THE AUTHENTIC ACTS AND ORIGINAL DEEDS, ETC. AN: 1709. BY Dom IBcnnet melDon, i).%).TB. a monk of ^t.cJBDmunD's, Paris. STANBROOK, WORCESTER: THE ABBEY OF OUR LADY OF CONSOLATION. 1881. SFBSCEIISER'S COPY A CHRONICLE OF THE FROJVL THE RENEWING OF THEIR CONGREGATION IN THE DAYS OF QUEEN MARY, TO THE DEATH OF KING JAMES II BEING THE CHRONOLOGICAL NOTES OF DOM BENNET WELDON, O. S. B. Co C&e laig&t EetierenD illiam TBernarD C3Uatl)ome, D. D, ©. ^. 'B. TBifljop of TBirmingtam, Cfiis toorfe, Draton from tfje 3rc[)ii)es of Us a^onaflic &ome, anD note fira puiiltfljeD at Us requeft, is, toitb etierp feeling of eUeem ann reference, DetiicateD Dp Us lorDlijip's Ijumtile servant C&e (ZEDitor. ^t. ©regorp's Ipriorp, DotonfiDe, TBatt). jFeafl of %t TBeneDift, mDccclrrri. PEEFACB THE following work is offered to the public as a contribution to the history of the CathoUc Church in England during the seventeenth century. There ia, indeed, a good deal told us in it concerning the history of the Benedictines ia England before that period, but the chief value of these Chronological Notes con sists in the information which they contain on the reestahlishment of the English Benedictines under the first of the Stuarts, and the chief events in connection with their body down to the death of James IL TiU very recently the supply of works illustrative of the condition of the CathoUc Church in this country subsequent to the Eeformation has been extremely scanty. -

Bulletin 359 July 2002

Registered Charity No: 272098 ISSN 0585-9980 SURREY ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY CASTLE ARCH, GUILDFORD GU1 3SX Tel/ Fax: 01483 532454 E-mail: [email protected] Website: ourworld.compuserve.com/homepages/surreyarch Bulletin 359 July 2002 Secdory of Trench W O R L D W A R D E F E N C E S O N T H E H O G ' S B A C K Top Fig: The 1948 RAF Aerial Photograph A SECOND WORLD WAR ANTI -TANK DITCH AT SEALE Alan Hall A group from Surrey Archaeological Society joined members of North East Hants Archaeological Society over the Bank Holiday weekend of 4th - 6th May 2002 in an excavation to investigate the nature of a soil mark showing on a 1948 RAF aerial photograph. The site lies on the southern slopes of the Hog's Back between Runfold and Seale with the soil mark running at an angle of 62° east of north between SU 881479 and SU 881479 at which point it changes its orientation southerly to 76° east of north before apparently taking a right-angle turn to cross the Hog's Back and continue thereafter in an approximately north-easterly direction. A t S U 8 8 2 8 8 4 7 9 2 3 a 1 2 m x 2 m t r e n c h r e v e a l e d a d i t c h 4 . 2 5 m i n w i d t h a n d 1.6m depth containing variable layers suggestive of "dump" filling. -

From: LIST of ENGLISH RELIGIOUS HOUSES Gasquet, F. A., English Monastic Life, Methuen & Co., London. 1904. 251-317. [Public

From: LIST OF ENGLISH RELIGIOUS HOUSES Gasquet, F. A., English Monastic Life, Methuen & Co., London. 1904. 251-317. [Public Domain text transcribed and prepared for HTML and PDF by Richenda Fairhurst, historyfish.net. July 2007. No commercial permissions granted. Text may contain errors. (Report errors to [email protected])] LIST OF ENGLISH RELIGIOUS HOUSES [Houses sorted by religious Order] An asterisk(*) prefixed to a religious house signifies that there are considerable remains extant. A dagger(†) prefixed signifies that there are sufficient remains to interest an archaeologist. No attention is paid to mere mounds or grass-covered heaps. For these marks as to remains the author is not responsible. They have kindly been contributed by Rev. Dr. Cox and Mr. W. H. St. John Hope, who desire it to be known that they do not in any way consider these marks exhaustive ; they merely represent those remains with which one or other, or both, are personally acquainted. The following abbreviations for the names of the religious Orders, etc., have been used in the list: — A. = Austin Canons. Franc. = Franciscan, or Grey Friars. A. (fs) = Austin Friars, or Hermits. Fran. (n.) = Franciscan nun. A. (n.) = Austin nuns. G. = Gilbertines(canons following the A. P. = Alien Priories. rule of St. Austin, and nuns A. (sep.) = Austin Canons of the holy that of St. Benedict.) Sepulchre H. = Hospitals. A. H. = Alien Hospitals H. (lep.) = Leper Hospitals. B. = Benedictines, or Black monks H.-A.(fs.) = Hospitals served by Austin Friars. B(fs.) = Bethelmite Friars H.-B.(fs.) = Hospitals served by Bethelmite B. (n.) = Benedictine nuns. -

Bell Frame Level 3

THE CHURCH OF ST. GEORGE THE MARTYR BOROUGH SOUTHWARK A LEVEL 3 RECORD OF THE BELL FRAME Compiled by Dr John C.Eisel FSA. December 2011 1 This report is produced by Dr. J.C. Eisel FSA 10 Lugg View Close Hereford HR1 1JF Tel. (01432) 271141 for The Archbishops’ Council Church House Great Smith Street London SW1P 3AZ Dr. J.C. Eisel is a research specialist on the development of bell frames and has acted as a consultant to English Heritage and as an adviser to the Church Buildings Commission. He has lectured on the subject to both the Institute of Field Archaeologists and to a seminar organised by the then Council for the Care of Churches. He was a contributor to Chris Pickford’s Bellframes. A practical guide to inspection and recording (1993), and to The Archaeology of Bellframes: Recording and Preservation (1996), edited by Christopher J. Brooke. Semi-retired, he undertakes the occasional commission. © J.C. Eisel 2011 Cover: Engraving of the church and spire of the church of St. George-the-Martyr, Southwark, published c.1776. 2 THE CHURCH OF ST. GEORGE THE MARTYR, BOROUGH, SOUTHWARK. A Level 3 record of the bell frame TEXT AND LAYOUT Dr. J.C. Eisel FSA SURVEY Dr. J.C. Eisel Mrs. M.P. Eisel ________________________________________ Contents 1. Introduction 2. Outline history of the church 3. History of the bells 4. The clock 5. The tower 6. The bells and fittings 7. The bell frame 8. The supporting timbers 9. The context of the bell frame 10. The significance of the bell frame 11. -

Tanner Street Park – Bermondsey Street Back Stories Number 1

Bermondsey Street Back Stories Number 1: Tanner Street Park’s 90th Anniversary By Jennie Howells May 2019 The Opening of Tanner Street Park in 1929 90th Anniversary Tanner Street Park lies at the junction of Tanner Street and Bermondsey Street, to the south of London Bridge station, Tooley Street and Tower Bridge. It was established in 1929 so this year is the 90th anniversary of its opening. It also celebrates the restoration and renovation of an important historical feature. Site of the Bermondsey Workhouse The park was laid out on land that had originally belonged to Bermondsey Abbey. This was later occupied by the Bermondsey Workhouse, built in 1791. The building was altered and extended, but was always subject to flooding and frequently overcrowded. Over the years conditions improved although it was never, nor was it intended to be, a welcoming place. It became known locally as ‘the Bastille’, formidable and dreaded by all. The Floor Plan of the workhouse in early years (Russell St has since been renamed Tanner St) For a temporary period, from 1915 to c1918, the workhouse building became a refuge for convalescent Belgian soldiers who would be referred on to another hospital, discharged or returned to their units. The hospital also provided office accommodation for the Military Bureau as well as temporary hospitality for soldiers on leave. A Park for Bermondsey’s Children The long and sometimes distressing history of the workhouse came to an end when, by 1928, it was closed and finally demolished. Bermondsey Borough Council owned half the site and the other half was purchased from charity trustees on condition that it was used as an open space.