Retrograde Fixation of the Ulna in Pediatric Forearm Fractures Treated with Elastic Stable Intramedullary Nailing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

6.3.3 Distal Radius and Wrist

6 Specific fractures 6.3 Forearm and hand 6.3.3 Distal radius and wrist 1 Assessment 657 1.1 Biomechanics 657 1.2 Pathomechanics and classification 657 1.3 Imaging 658 1.4 Associated lesions 659 1.5 Decision making 659 2 Surgical anatomy 660 2.1 Anatomy 660 2.2 Radiographic anatomy 660 2.3 Preoperative planning 661 2.4 Surgical approaches 662 2.4.1 Dorsal approach 2.4.2 Palmar approach 3 Management and surgical treatment 665 3.1 Type A—extraarticular fractures 665 3.2 Type B—partial articular fractures 667 3.3 Type C—complete articular fractures 668 3.4 Ulnar column lesions 672 3.4.1 Ulnar styloid fractures 3.4.2 Ulnar head, neck, and distal shaft fractures 3.5 Postoperative care 674 3.6 Complications 676 3.7 Results 676 4 Bibliography 677 5 Acknowledgment 677 656 PFxM2_Section_6_I.indb 656 9/19/11 2:45:49 PM Authors Daniel A Rikli, Doug A Campbell 6.3.3 Distal radius and wrist of this stable pivot. The TFCC allows independent flexion/ 1 Assessment extension, radial/ulnar deviation, and pronation/supination of the wrist. It therefore plays a crucial role in the stability of 1.1 Biomechanics the carpus and forearm. Significant forces are transmitted across the ulnar column, especially while making a tight fist. The three-column concept (Fig 6.3.3-1) [1] is a helpful bio- mechanical model for understanding the pathomechanics of 1.2 Pathomechanics and classification wrist fractures. The radial column includes the radial styloid and scaphoid fossa, the intermediate column consists of the Virtually all types of distal radial fractures, with the exception lunate fossa and sigmoid notch (distal radioulnar joint, DRUJ), of dorsal rim avulsion fractures, can be produced by hyper- and the ulnar column comprises the distal ulna (DRUJ) with extension forces [2]. -

Pearls and Pitfalls of Forearm Nailing

Current Concept Review Pearls and Pitfalls of Forearm Nailing Sreeharsha V. Nandyala, MD; Benjamin J. Shore, MD, MPH, FRCSC; Grant D. Hogue, MD Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, MA Abstract: Pediatric forearm fractures are one of the most common injuries that pediatric orthopaedic surgeons manage. Unstable fractures that have failed closed reduction and casting require surgical intervention in order to correct length, alignment, and rotation to optimize forearm range of motion and function. Flexible intramedullary nailing (FIN) is a powerful technique that has garnered widespread popularity and adaptation for this purpose. Surgeons must become familiar with the technical pearls and pitfalls associated with this technique in an effort to prevent complications. Key Concepts: • Flexible intramedullary nailing is a useful technique that is widely utilized for most unstable both-bone forearm fractures except in the setting of highly comminuted fracture patterns or in refractures with abundant intrame- dullary callus formation. • Proper contouring of the rod prior to insertion and bending of the tip will help decrease the risk of malunion and facilitate rod passage across the fracture site. • The surgeon must be aware of the numerous pitfalls that are associated with flexible intramedullary nailing and the methods to mitigate each complication. Introduction Flexible intramedullary nailing (FIN) offers several key As enthusiasm grows for FIN as a treatment for pediatric advantages for the management of those pediatric fore- forearm fractures, surgeons must also clearly understand arm fractures that are not amenable to closed treatment. the technical nuances, controversies, and strategies to These advantages include cosmetic incisions for nail in- mitigate complications associated with this technique. -

Distal Humerus Lateral Condyle Fracture and Monteggia Lesion in a 3-Year Old Child : a Case Report

Acta Orthop. Belg., 2008, 74, 542-545 CASE REPORT Distal humerus lateral condyle fracture and Monteggia lesion in a 3-year old child : A case report Rupen DATTANI, Surendra PATNAIK, Avdhoot KANTAK, Mohan LAL From East Surrey Hospital, Surrey, United Kingdom We describe a case of a Monteggia fracture disloca- DISCUSSION tion and an ipsilateral lateral humeral condyle frac- ture in a 3-year-old child. This is a rare combination Lateral condyle physeal fractures comprise 17% of injuries with no previously reported cases in the of all paediatric distal humerus fractures with a literature. This case emphasises that when a fracture peak incidence at 6 years of age (8). The mechanism is detected around an elbow there should be a high of injury is either an avulsion by the pull of the index of suspicion for other injuries in the region. common extensor origin owing to a varus stress Keywords : Monteggia fracture dislocation ; fracture of exerted on the extended elbow (‘pull off’ theory) or the humeral condyle ; elbow dislocation ; humerus a fall onto an extended upper extremity resulting fracture. in an axial load transmitted through the forearm, causing the radial head to impinge on the lateral head (‘push off’ theory) (2). Milch classified these fractures into two types (12). In type I injuries, the CASE REPORT fracture line courses lateral to the trochlea and into the capitello-trochlear groove representing a Salter- A 3-year-old boy presented to the emergency Harris type IV fracture : the elbow is usually stable department following a fall from a height onto his because the trochlea is intact. -

Upper Extremity Fractures

Department of Rehabilitation Services Physical Therapy Standard of Care: Distal Upper Extremity Fractures Case Type / Diagnosis: This standard applies to patients who have sustained upper extremity fractures that require stabilization either surgically or non-surgically. This includes, but is not limited to: Distal Humeral Fracture 812.4 Supracondylar Humeral Fracture 812.41 Elbow Fracture 813.83 Proximal Radius/Ulna Fracture 813.0 Radial Head Fractures 813.05 Olecranon Fracture 813.01 Radial/Ulnar shaft fractures 813.1 Distal Radius Fracture 813.42 Distal Ulna Fracture 813.82 Carpal Fracture 814.01 Metacarpal Fracture 815.0 Phalanx Fractures 816.0 Forearm/Wrist Fractures Radius fractures: • Radial head (may require a prosthesis) • Midshaft radius • Distal radius (most common) Residual deformities following radius fractures include: • Loss of radial tilt (Normal non fracture average is 22-23 degrees of radial tilt.) • Dorsal angulation (normal non fracture average palmar tilt 11-12 degrees.) • Radial shortening • Distal radioulnar (DRUJ) joint involvement • Intra-articular involvement with step-offs. Step-off of as little as 1-2 mm may increase the risk of post-traumatic arthritis. 1 Standard of Care: Distal Upper Extremity Fractures Copyright © 2007 The Brigham and Women's Hospital, Inc. Department of Rehabilitation Services. All rights reserved. Types of distal radius fracture include: • Colle’s (Dinner Fork Deformity) -- Mechanism: fall on an outstretched hand (FOOSH) with radial shortening, dorsal tilt of the distal fragment. The ulnar styloid may or may not be fractured. • Smith’s (Garden Spade Deformity) -- Mechanism: fall backward on a supinated, dorsiflexed wrist, the distal fragment displaces volarly. • Barton’s -- Mechanism: direct blow to the carpus or wrist. -

ISSN 2073 ISSN 2073 9990 East Cent. Afr. J. S

98 ISSN 20732073----99909990 East Cent. Afr. J. s urg Pisiform Dislocation and Distal Radius Ulna Fracture F.M. Kalande Department of Surgery, Ergerton University, Nakuru-Kenya. Email: [email protected] Background Pisiform dislocation is quite rare. In literature since the 40’s little discussion is documented about this. It is quite rare without other carpal bone dislocation. Pisiform dislocates when the wrist is forced into hypertension ;the flexor carpi ulnaris (FCU) tears of the pisiform and pisohamate ligament and or pisocarpitate ligament. Flexor Carpi ulnaris is a very powerful wrist flexor in extension the pisiform acts as a sesamoid bone enhancing its action. During such injury it is pulled in hypertension and displaces proximally or it may thereafter migrates distally. We report a rare condition where dislocation of pisiform is occurring not with carpal fractures or dislocation but with distal radius ulna fracture in a young skeletally immature boy, the treatment and outcome. Key words: pisiform, traumatic dislocation excision and radius/ulna fracture Case presentation We report a case of a 15-year old boy who presented with history of a fall while playing soccer at school. He sustained injury to his right wrist when he fell on an outreached hand, he developed immediate swelling and severe pain. On further evaluation there was tenderness over the wrist and the hypothenar eminence, and loss of range of motion due to pain. Neuronal assessment revealed normal function of the ulnar nerve . Operative AP View Pre-operative Lateral View. COSECSA/ASEA Publication ---East-East & Central African Journal of Surgery. Nov/Dec 2015 Vol. -

Assessing Forearm Fractures from Eight Prehistoric California Populations

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks Master's Theses Master's Theses and Graduate Research 2009 Assessing forearm fractures from eight prehistoric California populations Diane Marie DiGiuseppe San Jose State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses Recommended Citation DiGiuseppe, Diane Marie, "Assessing forearm fractures from eight prehistoric California populations" (2009). Master's Theses. 3707. DOI: https://doi.org/10.31979/etd.jm7h-xsgr https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses/3707 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses and Graduate Research at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ASSESSING FOREARM FRACTURES FROM EIGHT PREHISTORIC CALIFORNIA POPULATIONS A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Environmental Studies San Jose State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science by Diane Marie DiGiuseppe August 2009 UMI Number: 1478589 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI Dissertation Publishing UMI 1478589 Copyright 2010 by ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This edition of the work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. -

The Role of Locking Technology in the Hand

The Role of Locking Technology in the Hand David E. Ruchelsman, MDa,b, Chaitanya S. Mudgal, MD, MS(Orth), MCh(Orth)a,b,c, Jesse B. Jupiter, MDa,b,* KEYWORDS Locking plates Metacarpal and phalanx fractures Hand trauma Internal fixation of the hand and wrist has evolved acute bone loss, periarticular and metaphyseal in the last 4 decades. It is well accepted that stable fractures, osteopenic bone) and complex recon- internal fixation in the setting of combined muscu- structions for malunion, nonunion, or posttrau- loskeletal injuries involving the osseous skeleton matic deformities. Locked plates in the hand and soft-tissue envelope facilitates early rehabili- confer rigid or relative stability based on the clin- tation and promotes improved functional ical scenario being addressed. outcomes.1–4 Plate and screw fixation systems in In appropriately selected cases, locking plate the hand and wrist were originally predicated on technology may be helpful in addressing a variety the larger long-bone fracture fixation systems. of extraarticular and periarticular problems in the Locked plating establishes a fixed-angle construct hand and wrist. Clinical experience with locking (ie, functions as an internal-external fixator). technology in hand trauma remains relatively Angular-stable fixation has begun to revolutionize limited compared with its application for fractures the operative management of complex metadia- about the proximal humerus,5–8 distal humerus,9 physeal long-bone trauma, as well as periarticular distal radius,10–14 distal femur,15,16 periprosthetic and periprosthetic fractures, and has acquired femur,17,18 tibial plateau,19 proximal,20 and distal a growing role in the hand as well. -

Forearm Fractures Sean T

Forearm Fractures Sean T. Campbell, MD Assistant Attending Orthopedic Trauma Service Hospital for Special Surgery, New York, NY Core Curriculum V5 Objectives • Understand rationale for surgery for forearm fractures • Understand which segment is unstable based on injury pattern • Identify goals of surgery based on injury pattern • Review surgical techniques Core Curriculum V5 Introduction: Forearm Fractures • Young patients • Typically high energy injuries • Geriatric/osteopenic patients • May be low energy events • Mechanism • Fall on outstretched extremity • Direct blunt trauma Core Curriculum V5 Anatomy • Two bones that function as a forearm joint to allow rotation • Radius • Radial bow in coronal plane • Ulna • Proximal dorsal angulation in sagittal plane • Not a straight bone • Distinct bow in coronal plane (see next slides) • Proximal radioulnar joint (PRUJ) • Articulation of radial head with proximal ulna • Distal radioulnar joint • Articulation of ulnar head with distal radius • Interosseous membrane Hreha J+, Snow B+ Image from: Jarvie, Geoff C. MD, MHSc, FRCSC*; Kilb, Brett MD, MSc, BS*,†; Willing, Ryan PhD, BEng‡; King, Graham J. MD, MSc, FRCSC‡; Daneshvar, Parham MD, BS* Apparent Proximal Ulna Dorsal Angulation Variation Due to Ulnar Rotation, Journal of Orthopaedic Trauma: April 2019 - Volume 33 - Issue 4 - p e120-e123 doi: 10.1097/BOT.0000000000001408 Core Curriculum V5 Anatomy • Radial bow allows for pronosupination • Must be restored surgically when compromised • Multiple methods for assessment of radial bow • Comparison to contralateral images • Direct anatomic reduction of simple fractures • Biceps tuberosity 180 degrees of radial styloid • Note opposite apex medial bow of ulna • Not a straight bone Image from: Rockwood and Green, 9e, fig 41-9 Core Curriculum V5 Anatomy • Depiction of ulnar shape, noting proximal ulnar dorsal angulation (PUDA) in the top image, and varus angulation in the bottom image Image from: Jarvie, Geoff C. -

Distal Ulna Fracture with Delayed Ulnar Nerve Palsy in a Baseball Player

A Case Report & Literature Review Distal Ulna Fracture With Delayed Ulnar Nerve Palsy in a Baseball Player Charles B. Pasque, MD, Clark Pearson, ATC, Bradley Margo, MD, and Robert Ethel, BS a high and inside pitched ball from a right-handed pitcher Abstract struck the volar-ulnar aspect of his right forearm. Examina- We present a case report of a college baseball player tion in the training room and emergency department revealed who sustained a blunt-trauma, distal-third ulna fracture moderate swelling and ecchymosis over the distal third of the from a thrown ball with delayed presentation of ulnar ulna. He had a normal neurovascular examination, including nerve palsy. Even after his ulna fracture had healed, the normal sensation to light touch and normal finger abduction/ nerve injury made it difficult for the athlete to control a adduction and wrist flexion/extension. He was otherwise baseball while throwing, resulting in a delayed return to healthy. Radiographs of the right forearm showed a minimally full baseball activity for 3 to 4 months. He had almost displaced transverse fracture of the distal third of the ulna complete nerve recovery by 6 months after his injury (Figures 1A, 1B). and complete nerve recovery by 1 year after his injury. The patient was initially treated with a well-padded, remov- able, long-arm posterior splint for 2 weeks with serial exami- nations each day in the training room. At 2-week follow-up, he reported less pain and swelling but stated that his hand lnar nerve injury leads to clawing of the ulnar digits had “felt funny” the past several days. -

DISTAL RADIUS FRACTURES: REHABILITATIVE EVALUATION and TREATMENT PDH Academy Course #OT-1901 | 5 CE HOURS

CONTINUING EDUCATION for Occupational Therapists DISTAL RADIUS FRACTURES: REHABILITATIVE EVALUATION AND TREATMENT PDH Academy Course #OT-1901 | 5 CE HOURS This course is offered for 0.5 CEUs (Intermediate level; Category 2 – Occupational Therapy Process: Evaluation; Category 2 – Occupational Therapy Process: Intervention; Category 2 – Occupational Therapy Process: Outcomes). The assignment of AOTA CEUs does not imply endorsement of specific course content, products, or clinical procedures by AOTA. Course Abstract This course addresses the rehabilitation of patients with distal radius fractures. It begins with a review of relevant terminology and anatomy, next speaks to medical intervention, and then examines the role of therapy as it pertains to evaluation, rehabilitation, and handling complications. It concludes with case studies. Target audience: Occupational Therapists, Occupational Therapy Assistants, Physical Therapists, Physical Therapist Assistants (no prerequisites). NOTE: Links provided within the course material are for informational purposes only. No endorsement of processes or products is intended or implied. Learning Objectives At the end of this course, learners will be able to: ❏ Differentiate between definitions and terminology pertaining to distal radius fractures ❏ Recall the normal anatomy and kinesiology of the wrist ❏ Identify elements of medical diagnosis and treatment of distal radius fractures ❏ Recognize roles of therapy as it pertains to the evaluation and rehabilitation of distal radius fractures ❏ Distinguish -

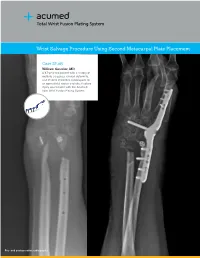

Wrist Salvage Procedure Using Second Metacarpal Plate Placement

Total Wrist Fusion Plating System Wrist Salvage Procedure Using Second Metacarpal Plate Placement Case Study William Geissler, MD A 47-year-old patient with a history of multiple surgeries, clinical deformity, and chronic infections subsequent to an open distal radius and ulna fracture injury was treated with the Acumed Total Wrist Fusion Plating System. Pre- and postoperative radiographs Acumed® is a global leader of innovative orthopaedic and medical solutions. We are dedicated to developing products, service methods, and approaches that improve patient care. Case Study | William Geissler, MD Anteroposterior radiograph Postoperative radiograph Lateral postoperative Wrist Salvage Procedure Using Second Metacarpal Plate Placement Intraoperative lateral fluoroscopic Patient History The patient is a 47-year-old male with a history of approximately 20 previous operations at an institution in other state. The patient’s original injury was an open fracture of distal radius and ulna. The patient underwent previous irrigation and debridement as well open reduction and internal fixation. Eventually the plates were removed, as the patient had a continued chronic infection to both the distal radius and ulna. Following several debridements, the patient had remained free of any drainage. One of the patient’s previous surgeries was an attempt at distal radioulnar joint stabilization. The patient presented with severe pain to the distal radius and marked clinical deformity to the wrist. The patient had limited active motion to the wrist as well as limited supination. On physical examination, any range of motion to the wrist was quite painful. The previous incisions were not red hot or warm and there was no active drainage. -

Wing Injuries- Approach to Diagnosis and Treatment- Kimberly a Mcmunn MS, MPH, DVM, CWR, CPH

Wing Injuries- Approach to Diagnosis and Treatment- Kimberly A McMunn MS, MPH, DVM, CWR, CPH Birds are highly adapted to flight, and preservation of flight capabilities is integral to the rehabilitation process. Each rehabilitator needs to work closely with a veterinarian to diagnose and treat the cause of an inability to fly. Rehabilitators are vital to the recovery of birds, providing necessary care and physical therapy during and after treatment/surgery. This talk will cover aspects of diagnosing and treatment of wing injures, from the perspective of the veterinarian. It will cover best approaches to various types of wing injures, as well as after-care and physical therapy recommendations. Wing injuries are extremely common in wild avian patients, often secondary to trauma. Early identification of wing injuries is critical to optimize the long-term prognosis, as is getting the bird to a veterinarian for care as soon as it is stabilized. Veterinarians are responsible for animal welfare, and are the experts best suited to evaluate a patient’s long-term prognosis.5 The goal of rehabilitation is to return our patients to the wild, which requires return to normal function. If a wild bird is unable to fly, forage, migrate, attract a mate, breed, and avoid predators, euthanasia may be the kindest option.5 Normal avian anatomy must be understood before it is possible to recognize and identify wing injuries. As mammals, we generally have a good comparison of human to mammalian anatomy. Birds are different in that they are highly adapted for flight, and the wing is most comparable to the mammalian forelimb.