Buckled, Bent Or Broken?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Effect of Yield Strength on Inelastic Buckling of Reinforcing

Mechanics and Mechanical Engineering Vol. 14, No. 2 (2010) 247{255 ⃝c Technical University of Lodz The Effect of Yield Strength on Inelastic Buckling of Reinforcing Bars Jacek Korentz Institute of Civil Engineering University of Zielona G´ora Licealna 9, 65{417 Zielona G´ora, Poland Received (13 June 2010) Revised (15 July 2010) Accepted (25 July 2010) The paper presents the results of numerical analyses of inelastic buckling of reinforcing bars of various geometrical parameters, made of steel of various values of yield strength. The results of the calculations demonstrate that the yield strength of the steel the bars are made of influences considerably the equilibrium path of the compressed bars within the range of postyielding deformations Comparative diagrams of structural behaviour (loading paths) of thin{walled sec- tions under investigation for different strain rates are presented. Some conclusions and remarks concerning the strain rate influence are derived. Keywords: Reinforcing bars, inelastic buckling, yield strength, tensil strength 1. Introduction The impact of some exceptional loads, e.g. seismic loads, on a structure may re- sult in the occurrence of post{critical states. Therefore the National Standards regulations for designing reinforced structures on seismically active areas e.g. EC8 [15] require the ductility of a structure to be examined on a cross{sectional level, and additionally, the structures should demonstrate a suitable level of global duc- tility. The results of the examinations of members of reinforced concrete structures show that inelastic buckling of longitudinal reinforcement bars occurs in the state of post{critical deformations, [1, 2, 4, 7], and in some cases it occurs yet within the range of elastic deformations [8]. -

Greenstick Fracture Soft Cast No FU

Orthopaedic Department York Teaching Hospital This is a follow-up letter to your recent telephone consultation with the fracture care team explaining the ongoing management of your injury. Your case has been reviewed by an Orthopaedic Consultant (Bone Specialist) and Fracture Care Physiotherapist. You have sustained a greenstick fracture to your distal radius and/or ulna (forearm just before the wrist). This is a specific type of fracture that occurs in children’s bones Healing: This normally takes approximately 4 - 6 weeks to heal. It is normal for it to continue to ache a bit for a few weeks after this. Pain and swelling: Take pain killers as needed. The plaster backslab helps healing by keeping the bones in a good position. Elevate the arm to reduce swelling for the first few days Using your arm: You may use the arm as pain allows. It is important to keep the elbow moving to prevent stiffness. Follow up: There is a small chance that this fracture can displace (move). Therefore we routinely recommend a repeat x ray at 1 week after the injury and a new plaster cast. Arrangements for this appointment should have been made during your telephone consultation. Should you need to reschedule this appointment please see contact details at the top of this letter. Area of injury: If you are worried that you are unable to follow this rehabilitation plan, Or, if you are experiencing pain or symptoms, other than at the site of the original injury or surrounding area, or have any questions, then please phone the Fracture Care Team for advice. -

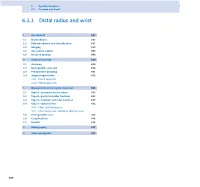

6.3.3 Distal Radius and Wrist

6 Specific fractures 6.3 Forearm and hand 6.3.3 Distal radius and wrist 1 Assessment 657 1.1 Biomechanics 657 1.2 Pathomechanics and classification 657 1.3 Imaging 658 1.4 Associated lesions 659 1.5 Decision making 659 2 Surgical anatomy 660 2.1 Anatomy 660 2.2 Radiographic anatomy 660 2.3 Preoperative planning 661 2.4 Surgical approaches 662 2.4.1 Dorsal approach 2.4.2 Palmar approach 3 Management and surgical treatment 665 3.1 Type A—extraarticular fractures 665 3.2 Type B—partial articular fractures 667 3.3 Type C—complete articular fractures 668 3.4 Ulnar column lesions 672 3.4.1 Ulnar styloid fractures 3.4.2 Ulnar head, neck, and distal shaft fractures 3.5 Postoperative care 674 3.6 Complications 676 3.7 Results 676 4 Bibliography 677 5 Acknowledgment 677 656 PFxM2_Section_6_I.indb 656 9/19/11 2:45:49 PM Authors Daniel A Rikli, Doug A Campbell 6.3.3 Distal radius and wrist of this stable pivot. The TFCC allows independent flexion/ 1 Assessment extension, radial/ulnar deviation, and pronation/supination of the wrist. It therefore plays a crucial role in the stability of 1.1 Biomechanics the carpus and forearm. Significant forces are transmitted across the ulnar column, especially while making a tight fist. The three-column concept (Fig 6.3.3-1) [1] is a helpful bio- mechanical model for understanding the pathomechanics of 1.2 Pathomechanics and classification wrist fractures. The radial column includes the radial styloid and scaphoid fossa, the intermediate column consists of the Virtually all types of distal radial fractures, with the exception lunate fossa and sigmoid notch (distal radioulnar joint, DRUJ), of dorsal rim avulsion fractures, can be produced by hyper- and the ulnar column comprises the distal ulna (DRUJ) with extension forces [2]. -

Lecture 42: Failure Analysis – Buckling of Columns Joshua Pribe Fall 2019 Lecture Book: Ch

ME 323 – Mechanics of Materials Lecture 42: Failure analysis – Buckling of columns Joshua Pribe Fall 2019 Lecture Book: Ch. 18 Stability and equilibrium What happens if we are in a state of unstable equilibrium? Stable Neutral Unstable 2 Buckling experiment There is a critical stress at which buckling occurs depending on the material and the geometry How do the material properties and geometric parameters influence the buckling stress? 3 Euler buckling equation Consider static equilibrium of the buckled pinned-pinned column 4 Euler buckling equation We have a differential equation for the deflection with BCs at the pins: d 2v EI+= Pv( x ) 0 v(0)== 0and v ( L ) 0 dx2 The solution is: P P A = 0 v(s x) = Aco x+ Bsin x with EI EI PP Bsin L= 0 L = n , n = 1, 2, 3, ... EI EI 5 Effect of boundary conditions Critical load and critical stress for buckling: EI EA P = 22= cr L2 2 e (Legr ) 2 E cr = 2 (Lreg) I r = Pinned- Pinned- Fixed- where g Fixed- A pinned fixed fixed is the “radius of gyration” free LLe = LLe = 0.7 LLe = 0.5 LLe = 2 6 Modifications to Euler buckling theory Euler buckling equation: works well for slender rods Needs to be modified for smaller “slenderness ratios” (where the critical stress for Euler buckling is at least half the yield strength) 7 Summary L 2 E Critical slenderness ratio: e = r 0.5 gYc Euler buckling (high slenderness ratio): LL 2 E EI If ee : = or P = 2 rr cr 2 cr L2 gg c (Lreg) e Johnson bucklingI (low slenderness ratio): r = 2 g Lr LLeeA ( eg) If : =−1 rr cr2 Y gg c 2 Lr ( eg)c with radius of gyration 8 Summary Effective length from the boundary conditions: Pinned- Pinned- Fixed- LL= LL= 0.7 FixedLL=- 0.5 pinned fixed e fixede e LL= 2 free e 9 Example 18.1 Determine the critical buckling load Pcr of a steel pipe column that has a length of L with a tubular cross section of inner radius ri and thickness t. -

Pearls and Pitfalls of Forearm Nailing

Current Concept Review Pearls and Pitfalls of Forearm Nailing Sreeharsha V. Nandyala, MD; Benjamin J. Shore, MD, MPH, FRCSC; Grant D. Hogue, MD Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, MA Abstract: Pediatric forearm fractures are one of the most common injuries that pediatric orthopaedic surgeons manage. Unstable fractures that have failed closed reduction and casting require surgical intervention in order to correct length, alignment, and rotation to optimize forearm range of motion and function. Flexible intramedullary nailing (FIN) is a powerful technique that has garnered widespread popularity and adaptation for this purpose. Surgeons must become familiar with the technical pearls and pitfalls associated with this technique in an effort to prevent complications. Key Concepts: • Flexible intramedullary nailing is a useful technique that is widely utilized for most unstable both-bone forearm fractures except in the setting of highly comminuted fracture patterns or in refractures with abundant intrame- dullary callus formation. • Proper contouring of the rod prior to insertion and bending of the tip will help decrease the risk of malunion and facilitate rod passage across the fracture site. • The surgeon must be aware of the numerous pitfalls that are associated with flexible intramedullary nailing and the methods to mitigate each complication. Introduction Flexible intramedullary nailing (FIN) offers several key As enthusiasm grows for FIN as a treatment for pediatric advantages for the management of those pediatric fore- forearm fractures, surgeons must also clearly understand arm fractures that are not amenable to closed treatment. the technical nuances, controversies, and strategies to These advantages include cosmetic incisions for nail in- mitigate complications associated with this technique. -

28 Combined Bending and Compression

CE 479 Wood Design Lecture Notes JAR Combined Bending and Compression (Sec 7.12 Text and NDS 01 Sec. 3.9) These members are referred to as beam-columns. The basic straight line interaction for bending and axial tension (Eq. 3.9-1, NDS 01) has been modified as shown in Section 3.9.2 of the NDS 01, Eq. (3.9-3) for the case of bending about one or both principal axis and axial compression. This equation is intended to represent the following conditions: • Column Buckling • Lateral Torsional Buckling of Beams • Beam-Column Interaction (P, M). The uniaxial compressive stress, fc = P/A, where A represents the net sectional area as per 3.6.3 28 CE 479 Wood Design Lecture Notes JAR The combination of bending and axial compression is more critical due to the P-∆ effect. The bending produced by the transverse loading causes a deflection ∆. The application of the axial load, P, then results in an additional moment P*∆; this is also know as second order effect because the added bending stress is not calculated directly. Instead, the common practice in design specifications is to include it by increasing (amplification factor) the computed bending stress in the interaction equation. 29 CE 479 Wood Design Lecture Notes JAR The most common case involves axial compression combined with bending about the strong axis of the cross section. In this case, Equation (3.9-3) reduces to: 2 ⎡ fc ⎤ fb1 ⎢ ⎥ + ≤ 1.0 F' ⎡ ⎛ f ⎞⎤ ⎣ c ⎦ F' 1 − ⎜ c ⎟ b1 ⎢ ⎜ F ⎟⎥ ⎣ ⎝ cE 1 ⎠⎦ and, the amplification factor is a number greater than 1.0 given by the expression: ⎛ ⎞ ⎜ ⎟ ⎜ 1 ⎟ Amplification factor for f = b1 ⎜ ⎛ f ⎞⎟ ⎜1 − ⎜ c ⎟⎟ ⎜ ⎜ F ⎟⎟ ⎝ ⎝ E 1 ⎠⎠ 30 CE 479 Wood Design Lecture Notes JAR Example of Application: The general interaction formula reduces to: 2 ⎡ fc ⎤ fb1 ⎢ ⎥ + ≤ 1.0 F' ⎡ ⎛ f ⎞⎤ ⎣ c ⎦ F' 1 − ⎜ c ⎟ b1 ⎢ ⎜ F ⎟⎥ ⎣ ⎝ cE 1 ⎠⎦ where: fc = actual compressive stress = P/A F’c = allowable compressive stress parallel to the grain = Fc*CD*CM*Ct*CF*CP*Ci Note: that F’c includes the CP adjustment factor for stability (Sec. -

Vanderbilt Sports Medicine

Alabama AAP Fall Meeting Sept.19-20, 2009 Pediatric Fracture Care for the Pediatrician Andrew Gregory, MD, FAAP, FACSM Assistant Professor Orthopedics & Pediatrics Program Director, Sports Medicine Fellowship Vanderbilt University Vanderbilt Sports Medicine Disclosure No conflict of interest - unfortunately for me, I have no financial relationships with companies making products regarding this topic to disclose Objectives Review briefly the differences of pediatric bone Review Pediatric Fracture Classification Discuss subtle fractures in kids Discuss a few other pediatric only conditions 1 Pediatric Skeleton Bone is relatively elastic and rubbery Periosteum is quite thick & active Ligaments are strong relative to the bone Presence of the physis - “weak link” Ligament injuries & dislocations are rare – “kids don’t sprain stuff” Fractures heal quickly and have the capacity to remodel Anatomy of Pediatric Bone Epiphysis Physis Metaphysis Diaphysis Apophysis Pediatric Fracture Classification Plastic Deformation – Bowing usually of fibula or ulna Buckle/ Torus – compression, stable Greenstick – unicortical tension Complete – Spiral, Oblique, Transverse Physeal – Salter-Harris Apophyseal avulsion 2 Plastic deformation Bowing without fracture Often deformed requiring reduction Buckle (Torus) Fracture Buckled Periosteum – Metaphyseal/ diaphyseal junction Greenstick Fracture Cortex Broken on Only One Side – Incomplete 3 Complete Fractures Transverse – Perpendicular to the bone Oblique – Across the bone at 45-60 o – Unstable Spiral – Rotational -

Pediatric Orthopedic Injuries… … from an ED State of Mind

Traumatic Orthopedics Peds RC Exam Review February 28, 2019 Dr. Naminder Sandhu, FRCPC Pediatric Emergency Medicine Objectives to cover today • Normal bone growth and function • Common radiographic abnormalities in MSK diseases • Part 1: Atraumatic – Congenital abnormalities – Joint and limb pain – Joint deformities – MSK infections – Bone tumors – Common gait disorders • Part 2: Traumatic – Common pediatric fractures and soft tissue injuries by site Overview of traumatic MSK pain Acute injuries • Fractures • Joint dislocations – Most common in ED: patella, digits, shoulder, elbow • Muscle strains – Eg. groin/adductors • Ligament sprains – Eg. Ankle, ACL/MCL, acromioclavicular joint separation Chronic/ overuse injuries • Stress fractures • Tendonitis • Bursitis • Fasciitis • Apophysitis Overuse injuries in the athlete WHY do they happen?? Extrinsic factors: • Errors in training • Inappropriate footwear Overuse injuries Intrinsic: • Poor conditioning – increased injuries early in season • Muscle imbalances – Weak muscle near strong (vastus medialus vs lateralus patellofemoral pain) – Excessive tightness: IT band, gastroc/soleus Sever disease • Anatomic misalignments – eg. pes planus, genu valgum or varum • Growth – strength and flexibility imbalances • Nutrition – eg. female athlete triad Misalignment – an intrinsic factor Apophysitis • *Apophysis = natural protruberance from a bone (2ndary ossification centres, often where tendons attach) • Examples – Sever disease (Calcaneal) – Osgood Schlatter disease (Tibial tubercle) – Sinding-Larsen-Johansson -

“Linear Buckling” Analysis Branch

Appendix A Eigenvalue Buckling Analysis 16.0 Release Introduction to ANSYS Mechanical 1 © 2015 ANSYS, Inc. February 27, 2015 Chapter Overview In this Appendix, performing an eigenvalue buckling analysis in Mechanical will be covered. Mechanical enables you to link the Eigenvalue Buckling analysis to a nonlinear Static Structural analysis that can include all types of nonlinearities. This will not be covered in this section. We will focused on Linear buckling. Contents: A. Background On Buckling B. Buckling Analysis Procedure C. Workshop AppA-1 2 © 2015 ANSYS, Inc. February 27, 2015 A. Background on Buckling Many structures require an evaluation of their structural stability. Thin columns, compression members, and vacuum tanks are all examples of structures where stability considerations are important. At the onset of instability (buckling) a structure will have a very large change in displacement {x} under essentially no change in the load (beyond a small load perturbation). F F Stable Unstable 3 © 2015 ANSYS, Inc. February 27, 2015 … Background on Buckling Eigenvalue or linear buckling analysis predicts the theoretical buckling strength of an ideal linear elastic structure. This method corresponds to the textbook approach of linear elastic buckling analysis. • The eigenvalue buckling solution of a Euler column will match the classical Euler solution. Imperfections and nonlinear behaviors prevent most real world structures from achieving their theoretical elastic buckling strength. Linear buckling generally yields unconservative results -

Buckling Failure Boundary for Cylindrical Tubes in Pure Bending

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2012-03-14 Buckling Failure Boundary for Cylindrical Tubes in Pure Bending Daniel Peter Miller Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Mechanical Engineering Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Miller, Daniel Peter, "Buckling Failure Boundary for Cylindrical Tubes in Pure Bending" (2012). Theses and Dissertations. 3131. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/3131 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Buckling Failure Boundary for Cylindrical Tubes in Pure Bending Daniel Peter Miller A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Kenneth L. Chase, Chair Carl D. Sorenson Brian D. Jensen Department of Mechanical Engineering Brigham Young University April 2012 Copyright © 2012 Daniel P. Miller All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT Buckling Failure Boundary for Cylindrical Tubes in Pure Bending Daniel Peter Miller Department of Mechanical Engineering Master of Science Bending of thin-walled tubing to a prescribed bend radius is typically performed by bending it around a mandrel of the desired bend radius, corrected for spring back. By eliminating the mandrel, costly setup time would be reduced, permitting multiple change of radius during a production run, and even intermixing different products on the same line. The principal challenge is to avoid buckling, as the mandrel and shoe are generally shaped to enclose the tube while bending. -

Distal Humerus Lateral Condyle Fracture and Monteggia Lesion in a 3-Year Old Child : a Case Report

Acta Orthop. Belg., 2008, 74, 542-545 CASE REPORT Distal humerus lateral condyle fracture and Monteggia lesion in a 3-year old child : A case report Rupen DATTANI, Surendra PATNAIK, Avdhoot KANTAK, Mohan LAL From East Surrey Hospital, Surrey, United Kingdom We describe a case of a Monteggia fracture disloca- DISCUSSION tion and an ipsilateral lateral humeral condyle frac- ture in a 3-year-old child. This is a rare combination Lateral condyle physeal fractures comprise 17% of injuries with no previously reported cases in the of all paediatric distal humerus fractures with a literature. This case emphasises that when a fracture peak incidence at 6 years of age (8). The mechanism is detected around an elbow there should be a high of injury is either an avulsion by the pull of the index of suspicion for other injuries in the region. common extensor origin owing to a varus stress Keywords : Monteggia fracture dislocation ; fracture of exerted on the extended elbow (‘pull off’ theory) or the humeral condyle ; elbow dislocation ; humerus a fall onto an extended upper extremity resulting fracture. in an axial load transmitted through the forearm, causing the radial head to impinge on the lateral head (‘push off’ theory) (2). Milch classified these fractures into two types (12). In type I injuries, the CASE REPORT fracture line courses lateral to the trochlea and into the capitello-trochlear groove representing a Salter- A 3-year-old boy presented to the emergency Harris type IV fracture : the elbow is usually stable department following a fall from a height onto his because the trochlea is intact. -

Upper Extremity Fractures

Department of Rehabilitation Services Physical Therapy Standard of Care: Distal Upper Extremity Fractures Case Type / Diagnosis: This standard applies to patients who have sustained upper extremity fractures that require stabilization either surgically or non-surgically. This includes, but is not limited to: Distal Humeral Fracture 812.4 Supracondylar Humeral Fracture 812.41 Elbow Fracture 813.83 Proximal Radius/Ulna Fracture 813.0 Radial Head Fractures 813.05 Olecranon Fracture 813.01 Radial/Ulnar shaft fractures 813.1 Distal Radius Fracture 813.42 Distal Ulna Fracture 813.82 Carpal Fracture 814.01 Metacarpal Fracture 815.0 Phalanx Fractures 816.0 Forearm/Wrist Fractures Radius fractures: • Radial head (may require a prosthesis) • Midshaft radius • Distal radius (most common) Residual deformities following radius fractures include: • Loss of radial tilt (Normal non fracture average is 22-23 degrees of radial tilt.) • Dorsal angulation (normal non fracture average palmar tilt 11-12 degrees.) • Radial shortening • Distal radioulnar (DRUJ) joint involvement • Intra-articular involvement with step-offs. Step-off of as little as 1-2 mm may increase the risk of post-traumatic arthritis. 1 Standard of Care: Distal Upper Extremity Fractures Copyright © 2007 The Brigham and Women's Hospital, Inc. Department of Rehabilitation Services. All rights reserved. Types of distal radius fracture include: • Colle’s (Dinner Fork Deformity) -- Mechanism: fall on an outstretched hand (FOOSH) with radial shortening, dorsal tilt of the distal fragment. The ulnar styloid may or may not be fractured. • Smith’s (Garden Spade Deformity) -- Mechanism: fall backward on a supinated, dorsiflexed wrist, the distal fragment displaces volarly. • Barton’s -- Mechanism: direct blow to the carpus or wrist.