Parsing Expression Grammars Made Practical

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Design and Evaluation of an Auto-Memoization Processor

DESIGN AND EVALUATION OF AN AUTO-MEMOIZATION PROCESSOR Tomoaki TSUMURA Ikuma SUZUKI Yasuki IKEUCHI Nagoya Inst. of Tech. Toyohashi Univ. of Tech. Toyohashi Univ. of Tech. Gokiso, Showa, Nagoya, Japan 1-1 Hibarigaoka, Tempaku, 1-1 Hibarigaoka, Tempaku, [email protected] Toyohashi, Aichi, Japan Toyohashi, Aichi, Japan [email protected] [email protected] Hiroshi MATSUO Hiroshi NAKASHIMA Yasuhiko NAKASHIMA Nagoya Inst. of Tech. Academic Center for Grad. School of Info. Sci. Gokiso, Showa, Nagoya, Japan Computing and Media Studies Nara Inst. of Sci. and Tech. [email protected] Kyoto Univ. 8916-5 Takayama Yoshida, Sakyo, Kyoto, Japan Ikoma, Nara, Japan [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT for microprocessors, and it made microprocessors faster. But now, the interconnect delay is going major and the This paper describes the design and evaluation of main memory and other storage units are going relatively an auto-memoization processor. The major point of this slower. In near future, high clock rate cannot achieve good proposal is to detect the multilevel functions and loops microprocessor performance by itself. with no additional instructions controlled by the compiler. Speedup techniques based on ILP (Instruction-Level This general purpose processor detects the functions and Parallelism), such as superscalar or SIMD, have been loops, and memoizes them automatically and dynamically. counted on. However, the effect of these techniques has Hence, any load modules and binary programs can gain proved to be limited. One reason is that many programs speedup without recompilation or rewriting. have little distinct parallelism, and it is pretty difficult for We also propose a parallel execution by multiple compilers to come across latent parallelism. -

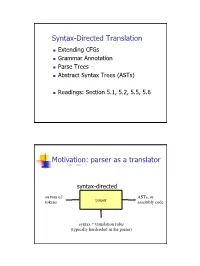

Syntax-Directed Translation, Parse Trees, Abstract Syntax Trees

Syntax-Directed Translation Extending CFGs Grammar Annotation Parse Trees Abstract Syntax Trees (ASTs) Readings: Section 5.1, 5.2, 5.5, 5.6 Motivation: parser as a translator syntax-directed translation stream of ASTs, or tokens parser assembly code syntax + translation rules (typically hardcoded in the parser) 1 Mechanism of syntax-directed translation syntax-directed translation is done by extending the CFG a translation rule is defined for each production given X Æ d A B c the translation of X is defined in terms of translation of nonterminals A, B values of attributes of terminals d, c constants To translate an input string: 1. Build the parse tree. 2. Working bottom-up • Use the translation rules to compute the translation of each nonterminal in the tree Result: the translation of the string is the translation of the parse tree's root nonterminal Why bottom up? a nonterminal's value may depend on the value of the symbols on the right-hand side, so translate a non-terminal node only after children translations are available 2 Example 1: arith expr to its value Syntax-directed translation: the CFG translation rules E Æ E + T E1.trans = E2.trans + T.trans E Æ T E.trans = T.trans T Æ T * F T1.trans = T2.trans * F.trans T Æ F T.trans = F.trans F Æ int F.trans = int.value F Æ ( E ) F.trans = E.trans Example 1 (cont) E (18) Input: 2 * (4 + 5) T (18) T (2) * F (9) F (2) ( E (9) ) int (2) E (4) * T (5) Annotated Parse Tree T (4) F (5) F (4) int (5) int (4) 3 Example 2: Compute type of expr E -> E + E if ((E2.trans == INT) and (E3.trans == INT) then E1.trans = INT else E1.trans = ERROR E -> E and E if ((E2.trans == BOOL) and (E3.trans == BOOL) then E1.trans = BOOL else E1.trans = ERROR E -> E == E if ((E2.trans == E3.trans) and (E2.trans != ERROR)) then E1.trans = BOOL else E1.trans = ERROR E -> true E.trans = BOOL E -> false E.trans = BOOL E -> int E.trans = INT E -> ( E ) E1.trans = E2.trans Example 2 (cont) Input: (2 + 2) == 4 1. -

Parallel Backtracking with Answer Memoing for Independent And-Parallelism∗

Under consideration for publication in Theory and Practice of Logic Programming 1 Parallel Backtracking with Answer Memoing for Independent And-Parallelism∗ Pablo Chico de Guzman,´ 1 Amadeo Casas,2 Manuel Carro,1;3 and Manuel V. Hermenegildo1;3 1 School of Computer Science, Univ. Politecnica´ de Madrid, Spain. (e-mail: [email protected], fmcarro,[email protected]) 2 Samsung Research, USA. (e-mail: [email protected]) 3 IMDEA Software Institute, Spain. (e-mail: fmanuel.carro,[email protected]) Abstract Goal-level Independent and-parallelism (IAP) is exploited by scheduling for simultaneous execution two or more goals which will not interfere with each other at run time. This can be done safely even if such goals can produce multiple answers. The most successful IAP implementations to date have used recomputation of answers and sequentially ordered backtracking. While in principle simplifying the implementation, recomputation can be very inefficient if the granularity of the parallel goals is large enough and they produce several answers, while sequentially ordered backtracking limits parallelism. And, despite the expected simplification, the implementation of the classic schemes has proved to involve complex engineering, with the consequent difficulty for system maintenance and extension, while still frequently running into the well-known trapped goal and garbage slot problems. This work presents an alternative parallel backtracking model for IAP and its implementation. The model fea- tures parallel out-of-order (i.e., non-chronological) backtracking and relies on answer memoization to reuse and combine answers. We show that this approach can bring significant performance advantages. Also, it can bring some simplification to the important engineering task involved in implementing the backtracking mechanism of previous approaches. -

Derivatives of Parsing Expression Grammars

Derivatives of Parsing Expression Grammars Aaron Moss Cheriton School of Computer Science University of Waterloo Waterloo, Ontario, Canada [email protected] This paper introduces a new derivative parsing algorithm for recognition of parsing expression gram- mars. Derivative parsing is shown to have a polynomial worst-case time bound, an improvement on the exponential bound of the recursive descent algorithm. This work also introduces asymptotic analysis based on inputs with a constant bound on both grammar nesting depth and number of back- tracking choices; derivative and recursive descent parsing are shown to run in linear time and constant space on this useful class of inputs, with both the theoretical bounds and the reasonability of the in- put class validated empirically. This common-case constant memory usage of derivative parsing is an improvement on the linear space required by the packrat algorithm. 1 Introduction Parsing expression grammars (PEGs) are a parsing formalism introduced by Ford [6]. Any LR(k) lan- guage can be represented as a PEG [7], but there are some non-context-free languages that may also be represented as PEGs (e.g. anbncn [7]). Unlike context-free grammars (CFGs), PEGs are unambiguous, admitting no more than one parse tree for any grammar and input. PEGs are a formalization of recursive descent parsers allowing limited backtracking and infinite lookahead; a string in the language of a PEG can be recognized in exponential time and linear space using a recursive descent algorithm, or linear time and space using the memoized packrat algorithm [6]. PEGs are formally defined and these algo- rithms outlined in Section 3. -

Dynamic Programming Via Static Incrementalization 1 Introduction

Dynamic Programming via Static Incrementalization Yanhong A. Liu and Scott D. Stoller Abstract Dynamic programming is an imp ortant algorithm design technique. It is used for solving problems whose solutions involve recursively solving subproblems that share subsubproblems. While a straightforward recursive program solves common subsubproblems rep eatedly and of- ten takes exp onential time, a dynamic programming algorithm solves every subsubproblem just once, saves the result, reuses it when the subsubproblem is encountered again, and takes p oly- nomial time. This pap er describ es a systematic metho d for transforming programs written as straightforward recursions into programs that use dynamic programming. The metho d extends the original program to cache all p ossibly computed values, incrementalizes the extended pro- gram with resp ect to an input increment to use and maintain all cached results, prunes out cached results that are not used in the incremental computation, and uses the resulting in- cremental program to form an optimized new program. Incrementalization statically exploits semantics of b oth control structures and data structures and maintains as invariants equalities characterizing cached results. The principle underlying incrementalization is general for achiev- ing drastic program sp eedups. Compared with previous metho ds that p erform memoization or tabulation, the metho d based on incrementalization is more powerful and systematic. It has b een implemented and applied to numerous problems and succeeded on all of them. 1 Intro duction Dynamic programming is an imp ortant technique for designing ecient algorithms [2, 44 , 13 ]. It is used for problems whose solutions involve recursively solving subproblems that overlap. -

CS 432 Fall 2020 Top-Down (LL) Parsing

CS 432 Fall 2020 Mike Lam, Professor Top-Down (LL) Parsing Compilation Current focus "Back end" Source code Tokens Syntax tree Machine code char data[20]; 7f 45 4c 46 01 int main() { 01 01 00 00 00 float x 00 00 00 00 00 = 42.0; ... return 7; } Lexing Parsing Code Generation & Optimization "Front end" Review ● Recognize regular languages with finite automata – Described by regular expressions – Rule-based transitions, no memory required ● Recognize context-free languages with pushdown automata – Described by context-free grammars – Rule-based transitions, MEMORY REQUIRED ● Add a stack! Segue KEY OBSERVATION: Allowing the translator to use memory to track parse state information enables a wider range of automated machine translation. Chomsky Hierarchy of Languages Recursively enumerable Context-sensitive Context-free Most useful Regular for PL https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chomsky_hierarchy Parsing Approaches ● Top-down: begin with start symbol (root of parse tree), and gradually expand non-terminals – Stack contains leaves that still need to be expanded ● Bottom-up: begin with terminals (leaves of parse tree), and gradually connect using non-terminals – Stack contains roots of subtrees that still need to be connected A V = E Top-down a E + E Bottom-up V V b c Top-Down Parsing root = createNode(S) focus = root A → V = E push(null) V → a | b | c token = nextToken() E → E + E loop: | V if (focus is non-terminal): B = chooseRuleAndExpand(focus) for each b in B.reverse(): focus.addChild(createNode(b)) push(b) A focus = pop() else if (token -

Total Parser Combinators

Total Parser Combinators Nils Anders Danielsson School of Computer Science, University of Nottingham, United Kingdom [email protected] Abstract The library has an interface which is very similar to those of A monadic parser combinator library which guarantees termination classical monadic parser combinator libraries. For instance, con- of parsing, while still allowing many forms of left recursion, is sider the following simple, left recursive, expression grammar: described. The library’s interface is similar to those of many other term :: factor term '+' factor parser combinator libraries, with two important differences: one is factor ::D atom j factor '*' atom that the interface clearly specifies which parts of the constructed atom ::D numberj '(' term ')' parsers may be infinite, and which parts have to be finite, using D j dependent types and a combination of induction and coinduction; We can define a parser which accepts strings from this grammar, and the other is that the parser type is unusually informative. and also computes the values of the resulting expressions, as fol- The library comes with a formal semantics, using which it is lows (the combinators are described in Section 4): proved that the parser combinators are as expressive as possible. mutual The implementation is supported by a machine-checked correct- term factor ness proof. D ] term >> λ n j D 1 ! Categories and Subject Descriptors D.1.1 [Programming Tech- tok '+' >> λ D ! niques]: Applicative (Functional) Programming; E.1 [Data Struc- factor >> λ n D 2 ! tures]; F.3.1 [Logics and Meanings of Programs]: Specifying and return .n n / 1 C 2 Verifying and Reasoning about Programs; F.4.2 [Mathematical factor atom Logic and Formal Languages]: Grammars and Other Rewriting D ] factor >> λ n Systems—Grammar types, Parsing 1 j tok '*' >>D λ ! D ! General Terms Languages, theory, verification atom >> λ n2 return .n n / D ! 1 ∗ 2 Keywords Dependent types, mixed induction and coinduction, atom number parser combinators, productivity, termination D tok '(' >> λ j D ! ] term >> λ n 1. -

Adaptive LL(*) Parsing: the Power of Dynamic Analysis

Adaptive LL(*) Parsing: The Power of Dynamic Analysis Terence Parr Sam Harwell Kathleen Fisher University of San Francisco University of Texas at Austin Tufts University [email protected] [email protected] kfi[email protected] Abstract PEGs are unambiguous by definition but have a quirk where Despite the advances made by modern parsing strategies such rule A ! a j ab (meaning “A matches either a or ab”) can never as PEG, LL(*), GLR, and GLL, parsing is not a solved prob- match ab since PEGs choose the first alternative that matches lem. Existing approaches suffer from a number of weaknesses, a prefix of the remaining input. Nested backtracking makes de- including difficulties supporting side-effecting embedded ac- bugging PEGs difficult. tions, slow and/or unpredictable performance, and counter- Second, side-effecting programmer-supplied actions (muta- intuitive matching strategies. This paper introduces the ALL(*) tors) like print statements should be avoided in any strategy that parsing strategy that combines the simplicity, efficiency, and continuously speculates (PEG) or supports multiple interpreta- predictability of conventional top-down LL(k) parsers with the tions of the input (GLL and GLR) because such actions may power of a GLR-like mechanism to make parsing decisions. never really take place [17]. (Though DParser [24] supports The critical innovation is to move grammar analysis to parse- “final” actions when the programmer is certain a reduction is time, which lets ALL(*) handle any non-left-recursive context- part of an unambiguous final parse.) Without side effects, ac- free grammar. ALL(*) is O(n4) in theory but consistently per- tions must buffer data for all interpretations in immutable data forms linearly on grammars used in practice, outperforming structures or provide undo actions. -

Parsing 1. Grammars and Parsing 2. Top-Down and Bottom-Up Parsing 3

Syntax Parsing syntax: from the Greek syntaxis, meaning “setting out together or arrangement.” 1. Grammars and parsing Refers to the way words are arranged together. 2. Top-down and bottom-up parsing Why worry about syntax? 3. Chart parsers • The boy ate the frog. 4. Bottom-up chart parsing • The frog was eaten by the boy. 5. The Earley Algorithm • The frog that the boy ate died. • The boy whom the frog was eaten by died. Slide CS474–1 Slide CS474–2 Grammars and Parsing Need a grammar: a formal specification of the structures allowable in Syntactic Analysis the language. Key ideas: Need a parser: algorithm for assigning syntactic structure to an input • constituency: groups of words may behave as a single unit or phrase sentence. • grammatical relations: refer to the subject, object, indirect Sentence Parse Tree object, etc. Beavis ate the cat. S • subcategorization and dependencies: refer to certain kinds of relations between words and phrases, e.g. want can be followed by an NP VP infinitive, but find and work cannot. NAME V NP All can be modeled by various kinds of grammars that are based on ART N context-free grammars. Beavis ate the cat Slide CS474–3 Slide CS474–4 CFG example CFG’s are also called phrase-structure grammars. CFG’s Equivalent to Backus-Naur Form (BNF). A context free grammar consists of: 1. S → NP VP 5. NAME → Beavis 1. a set of non-terminal symbols N 2. VP → V NP 6. V → ate 2. a set of terminal symbols Σ (disjoint from N) 3. -

Intercepting Functions for Memoization Arjun Suresh

Intercepting functions for memoization Arjun Suresh To cite this version: Arjun Suresh. Intercepting functions for memoization. Programming Languages [cs.PL]. Université Rennes 1, 2016. English. NNT : 2016REN1S106. tel-01410539v2 HAL Id: tel-01410539 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-01410539v2 Submitted on 11 May 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. ANNEE´ 2016 THESE` / UNIVERSITE´ DE RENNES 1 sous le sceau de l’Universite´ Bretagne Loire En Cotutelle Internationale avec pour le grade de DOCTEUR DE L’UNIVERSITE´ DE RENNES 1 Mention : Informatique Ecole´ doctorale Matisse present´ ee´ par Arjun SURESH prepar´ ee´ a` l’unite´ de recherche INRIA Institut National de Recherche en Informatique et Automatique Universite´ de Rennes 1 These` soutenue a` Rennes Intercepting le 10 Mai, 2016 devant le jury compose´ de : Functions Fabrice RASTELLO Charge´ de recherche Inria / Rapporteur Jean-Michel MULLER for Directeur de recherche CNRS / Rapporteur Sandrine BLAZY Memoization Professeur a` l’Universite´ de Rennes 1 / Examinateur Vincent LOECHNER Maˆıtre de conferences,´ Universite´ Louis Pasteur, Stras- bourg / Examinateur Erven ROHOU Directeur de recherche INRIA / Directeur de these` Andre´ SEZNEC Directeur de recherche INRIA / Co-directeur de these` If you save now you might benefit later. -

Abstract Syntax Trees & Top-Down Parsing

Abstract Syntax Trees & Top-Down Parsing Review of Parsing • Given a language L(G), a parser consumes a sequence of tokens s and produces a parse tree • Issues: – How do we recognize that s ∈ L(G) ? – A parse tree of s describes how s ∈ L(G) – Ambiguity: more than one parse tree (possible interpretation) for some string s – Error: no parse tree for some string s – How do we construct the parse tree? Compiler Design 1 (2011) 2 Abstract Syntax Trees • So far, a parser traces the derivation of a sequence of tokens • The rest of the compiler needs a structural representation of the program • Abstract syntax trees – Like parse trees but ignore some details – Abbreviated as AST Compiler Design 1 (2011) 3 Abstract Syntax Trees (Cont.) • Consider the grammar E → int | ( E ) | E + E • And the string 5 + (2 + 3) • After lexical analysis (a list of tokens) int5 ‘+’ ‘(‘ int2 ‘+’ int3 ‘)’ • During parsing we build a parse tree … Compiler Design 1 (2011) 4 Example of Parse Tree E • Traces the operation of the parser E + E • Captures the nesting structure • But too much info int5 ( E ) – Parentheses – Single-successor nodes + E E int 2 int3 Compiler Design 1 (2011) 5 Example of Abstract Syntax Tree PLUS PLUS 5 2 3 • Also captures the nesting structure • But abstracts from the concrete syntax a more compact and easier to use • An important data structure in a compiler Compiler Design 1 (2011) 6 Semantic Actions • This is what we’ll use to construct ASTs • Each grammar symbol may have attributes – An attribute is a property of a programming language construct -

Staged Parser Combinators for Efficient Data Processing

Staged Parser Combinators for Efficient Data Processing Manohar Jonnalagedda∗ Thierry Coppeyz Sandro Stucki∗ Tiark Rompf y∗ Martin Odersky∗ ∗LAMP zDATA, EPFL {first.last}@epfl.ch yOracle Labs: {first.last}@oracle.com Abstract use the language’s abstraction capabilities to enable compo- Parsers are ubiquitous in computing, and many applications sition. As a result, a parser written with such a library can depend on their performance for decoding data efficiently. look like formal grammar descriptions, and is also readily Parser combinators are an intuitive tool for writing parsers: executable: by construction, it is well-structured, and eas- tight integration with the host language enables grammar ily maintainable. Moreover, since combinators are just func- specifications to be interleaved with processing of parse re- tions in the host language, it is easy to combine them into sults. Unfortunately, parser combinators are typically slow larger, more powerful combinators. due to the high overhead of the host language abstraction However, parser combinators suffer from extremely poor mechanisms that enable composition. performance (see Section 5) inherent to their implementa- We present a technique for eliminating such overhead. We tion. There is a heavy penalty to be paid for the expres- use staging, a form of runtime code generation, to dissoci- sivity that they allow. A grammar description is, despite its ate input parsing from parser composition, and eliminate in- declarative appearance, operationally interleaved with input termediate data structures and computations associated with handling, such that parts of the grammar description are re- parser composition at staging time. A key challenge is to built over and over again while input is processed.