Is Ovophis Okinavensis Active Only in the Cool Season?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nansei Islands Biological Diversity Evaluation Project Report 1 Chapter 1

Introduction WWF Japan’s involvement with the Nansei Islands can be traced back to a request in 1982 by Prince Phillip, Duke of Edinburgh. The “World Conservation Strategy”, which was drafted at the time through a collaborative effort by the WWF’s network, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), and the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), posed the notion that the problems affecting environments were problems that had global implications. Furthermore, the findings presented offered information on precious environments extant throughout the globe and where they were distributed, thereby providing an impetus for people to think about issues relevant to humankind’s harmonious existence with the rest of nature. One of the precious natural environments for Japan given in the “World Conservation Strategy” was the Nansei Islands. The Duke of Edinburgh, who was the President of the WWF at the time (now President Emeritus), naturally sought to promote acts of conservation by those who could see them through most effectively, i.e. pertinent conservation parties in the area, a mandate which naturally fell on the shoulders of WWF Japan with regard to nature conservation activities concerning the Nansei Islands. This marked the beginning of the Nansei Islands initiative of WWF Japan, and ever since, WWF Japan has not only consistently performed globally-relevant environmental studies of particular areas within the Nansei Islands during the 1980’s and 1990’s, but has put pressure on the national and local governments to use the findings of those studies in public policy. Unfortunately, like many other places throughout the world, the deterioration of the natural environments in the Nansei Islands has yet to stop. -

Antimicrobial Peptides in Reptiles

Pharmaceuticals 2014, 7, 723-753; doi:10.3390/ph7060723 OPEN ACCESS pharmaceuticals ISSN 1424-8247 www.mdpi.com/journal/pharmaceuticals Review Antimicrobial Peptides in Reptiles Monique L. van Hoek National Center for Biodefense and Infectious Diseases, and School of Systems Biology, George Mason University, MS1H8, 10910 University Blvd, Manassas, VA 20110, USA; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-703-993-4273; Fax: +1-703-993-7019. Received: 6 March 2014; in revised form: 9 May 2014 / Accepted: 12 May 2014 / Published: 10 June 2014 Abstract: Reptiles are among the oldest known amniotes and are highly diverse in their morphology and ecological niches. These animals have an evolutionarily ancient innate-immune system that is of great interest to scientists trying to identify new and useful antimicrobial peptides. Significant work in the last decade in the fields of biochemistry, proteomics and genomics has begun to reveal the complexity of reptilian antimicrobial peptides. Here, the current knowledge about antimicrobial peptides in reptiles is reviewed, with specific examples in each of the four orders: Testudines (turtles and tortosises), Sphenodontia (tuataras), Squamata (snakes and lizards), and Crocodilia (crocodilans). Examples are presented of the major classes of antimicrobial peptides expressed by reptiles including defensins, cathelicidins, liver-expressed peptides (hepcidin and LEAP-2), lysozyme, crotamine, and others. Some of these peptides have been identified and tested for their antibacterial or antiviral activity; others are only predicted as possible genes from genomic sequencing. Bioinformatic analysis of the reptile genomes is presented, revealing many predicted candidate antimicrobial peptides genes across this diverse class. The study of how these ancient creatures use antimicrobial peptides within their innate immune systems may reveal new understandings of our mammalian innate immune system and may also provide new and powerful antimicrobial peptides as scaffolds for potential therapeutic development. -

Venom Proteomics and Antivenom Neutralization for the Chinese

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Venom proteomics and antivenom neutralization for the Chinese eastern Russell’s viper, Daboia Received: 27 September 2017 Accepted: 6 April 2018 siamensis from Guangxi and Taiwan Published: xx xx xxxx Kae Yi Tan1, Nget Hong Tan1 & Choo Hock Tan2 The eastern Russell’s viper (Daboia siamensis) causes primarily hemotoxic envenomation. Applying shotgun proteomic approach, the present study unveiled the protein complexity and geographical variation of eastern D. siamensis venoms originated from Guangxi and Taiwan. The snake venoms from the two geographical locales shared comparable expression of major proteins notwithstanding variability in their toxin proteoforms. More than 90% of total venom proteins belong to the toxin families of Kunitz-type serine protease inhibitor, phospholipase A2, C-type lectin/lectin-like protein, serine protease and metalloproteinase. Daboia siamensis Monovalent Antivenom produced in Taiwan (DsMAV-Taiwan) was immunoreactive toward the Guangxi D. siamensis venom, and efectively neutralized the venom lethality at a potency of 1.41 mg venom per ml antivenom. This was corroborated by the antivenom efective neutralization against the venom procoagulant (ED = 0.044 ± 0.002 µl, 2.03 ± 0.12 mg/ml) and hemorrhagic (ED50 = 0.871 ± 0.159 µl, 7.85 ± 3.70 mg/ ml) efects. The hetero-specifc Chinese pit viper antivenoms i.e. Deinagkistrodon acutus Monovalent Antivenom and Gloydius brevicaudus Monovalent Antivenom showed negligible immunoreactivity and poor neutralization against the Guangxi D. siamensis venom. The fndings suggest the need for improving treatment of D. siamensis envenomation in the region through the production and the use of appropriate antivenom. Daboia is a genus of the Viperinae subfamily (family: Viperidae), comprising a group of vipers commonly known as Russell’s viper native to the Old World1. -

Kumejima Island, Japan

O . kikuzatoi through a series of field surveys as below. Current Herpetology 23(2): 73-80, December 2004 (c)2004 by The Herpetological Society of Japan Field Observations on a Highly Endangered Snake, Opisthotropis kikuzatoi (Squamata: Colubridae), Endemic to Kumejima Island, Japan HIDETOSHI OTA* Tropical Biosphere Research Center, University of the Ryukyus, Nishihara, Okinawa 903-0213, JAPAN Abstract: The Kikuzato's brook snake, Opisthotropis kikuzatoi, is a highly endangered aquatic or semiaquatic species endemic to Kumejima Island of the Okinawa Group, Ryukyu Archipelago. Field studies were carried out for some ecological aspects of this species by visiting its habitat almost every month from April 1996 to March 1997. The results demonstrate that the snake is active almost throughout the year. It is also suggested that the snake tends to be diurnal in the warmer season, and nocturnal in the cooler season. Observations on a case of autonomous emergence onto the land, very slow growth, and predation on small crabs, are also provided. Key words: Opisthotropis kikuzatoi, Field census; Activity pattern; Body temper- ature; Kumejima Island INTRODUCTION broadleaf evergreen forest: see below), led Environment Agency of Japan assign O. The Kikuzato's brook snake Opisthotropis kikuzatoi to the highest Red List Category kikuzatoi, is a small colubrid species endemic (IA) as one of the two most critically endan- to Kumejima Island of the Okinawa Group, gered reptiles of Japan (Matsui, 1991; Ota, Ryukyu Archipelago. Since its original 2000). This snake is also protected by laws of description by Okada and Takara (1958: as a both the National Government of Japan and member of the genus Liopeltis), no more than the Prefectural Government of Okinawa (Ota, ten individuals have been known to science 2000). -

Morphological and Genetic Verification of Ovophis Tonkinensis (Bourret, 1934) in Hong Kong

Herpetology Notes, volume 10: 457-461 (2017) (published online on 06 September 2017) Morphological and genetic verification of Ovophis tonkinensis (Bourret, 1934) in Hong Kong Jonathan J. Fong1, Alessandro Grioni2, Paul Crow2 and Ka-shing Cheung3,* Abstract. Hong Kong lies in the putative ranges of two Ovophis species: O. makazayazaya (Sichuan and Yunnan Provinces, Taiwan, and northern Vietnam) and O. tonkinensis (Guangxi, Guangdong, and Hainan Provinces, and northern Vietnam). It is unclear which Ovophis species is/are present in Hong Kong. Previous studies identified O. tonkinensis using morphology, but without molecular data. In this study, we verified the presence of O. tonkinensis in Hong Kong using molecular (four mitochondrial DNA loci) and morphological data of two specimens. The clade that is currently identified as Ovophis tonkinensis has a large geographic range and relatively deep divergences, hinting that its taxonomy requires further work. Key words. Hong Kong, Ovophis tonkinensis, Ovophis makazayazaya, reptile, snake. Introduction makazayazaya (Karsen et al. 1998). Malhotra et al. (2011) included four Ovophis specimens from Hong Kong The Asian pitviper genus Ovophis has had a (BMNH 1983 281–284) in their morphometric analyses. complicated taxonomic history. Previously, Ovophis These four specimens grouped with O. tonkinensis was believed to contain three species (O. chaseni specimens from northern Vietnam and southern China. (Smith, 1931), O. okinavensis (Boulenger, 1892), O. Studies in areas close to Hong Kong also confirmed the monticola (Gunther, 1864; 4 subspecies)) (McDiarmid presence of O. tonkinensis, including Hainan Province et al. 1999). However, Malhotra and Thorpe (2004) (morphology: David (1995), David (2001), Wang et removed the first two species from this genus so that al. -

A Biogeographic Synthesis of the Amphibians and Reptiles of Indochina

BAIN & HURLEY: AMPHIBIANS OF INDOCHINA & REPTILES & HURLEY: BAIN Scientific Publications of the American Museum of Natural History American Museum Novitates A BIOGEOGRAPHIC SYNTHESIS OF THE Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History Anthropological Papers of the American Museum of Natural History AMPHIBIANS AND REPTILES OF INDOCHINA Publications Committee Robert S. Voss, Chair Board of Editors Jin Meng, Paleontology Lorenzo Prendini, Invertebrate Zoology RAOUL H. BAIN AND MARTHA M. HURLEY Robert S. Voss, Vertebrate Zoology Peter M. Whiteley, Anthropology Managing Editor Mary Knight Submission procedures can be found at http://research.amnh.org/scipubs All issues of Novitates and Bulletin are available on the web from http://digitallibrary.amnh.org/dspace Order printed copies from http://www.amnhshop.com or via standard mail from: American Museum of Natural History—Scientific Publications Central Park West at 79th Street New York, NY 10024 This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (permanence of paper). AMNH 360 BULLETIN 2011 On the cover: Leptolalax sungi from Van Ban District, in northwestern Vietnam. Photo by Raoul H. Bain. BULLETIN OF THE AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY A BIOGEOGRAPHIC SYNTHESIS OF THE AMPHIBIANS AND REPTILES OF INDOCHINA RAOUL H. BAIN Division of Vertebrate Zoology (Herpetology) and Center for Biodiversity and Conservation, American Museum of Natural History Life Sciences Section Canadian Museum of Nature, Ottawa, ON Canada MARTHA M. HURLEY Center for Biodiversity and Conservation, American Museum of Natural History Global Wildlife Conservation, Austin, TX BULLETIN OF THE AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY Number 360, 138 pp., 9 figures, 13 tables Issued November 23, 2011 Copyright E American Museum of Natural History 2011 ISSN 0003-0090 CONTENTS Abstract......................................................... -

With a Key to the Complex in China and Adjacent Areas

s c^ ^ TRANSLATIONS OF RECENT DESCRIPTIONS OF ^^ PT CHINESE PITVIPERS OF THE TRIMERESURUS-COMFLEX (SERPENTES, VIPERIDAE), WITH A KEY TO THE COMPLEX IN CHINA AND ADJACENT AREAS Patrick David Laboratoire des Reptiles et Amphibiens Museum national d'Histoire naturelle, Paris & Haiyan Tong Laboratoire de Paleontologie Universite Paris-VI SMITHSONIAN HERPETOLOGICAL INFORMATION SERVICE NO. 112 1997 SMITHSONIAN HERPETOLOGICAL INFORMATION SERVICE The SHIS series publishes and distributes translations, bibliographies, indices, and similar items judged useful to individuals interested in the biology of amphibians and reptiles, but unlikely to be published in the normal technical journals. Single copies are distributed free to interested individuals. Libraries, herpetological associations, and research laboratories are invited to exchange their publications with the Division of Amphibians and Reptiles. We wish to encourage individuals to share their bibliographies, translations, etc. with other herpetologists through the SHIS series. If you have such items please contact George Zug for instructions on preparation and submission. Contributors receive 50 free copies. Please address all requests for copies and inquiries to George Zug, Division of Amphibians and Reptiles, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC 20560 USA, Please include a self-addressed mailing label with requests. Historical perspective The renewed interest in herpetological researches that occurred in the 1970's in the People's Repubhc of China (hereafter merely referred to as China) led to the descriptions of many new taxa. Between 1972 and 1995, 17 species and 14 subspecies of snakes were described as new, either by Chinese or foreign authors. All species are still considered as valid, whereas seven subspecies proved to be junior synonyms of other taxa. -

On the Status of Trimeresurus Monticola Meridionalis Bourret, 1935 (Squamata: Viperidae)

Zootaxa 3304: 43–53 (2012) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2012 · Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) On the status of Trimeresurus monticola meridionalis Bourret, 1935 (Squamata: Viperidae) PATRICK DAVID1 & GERNOT VOGEL2 1Reptiles & Amphibiens, UMR 7205 OSEB, Département Systématique et Évolution, CP 30, Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, 57 rue Cuvier, 75231 Paris Cedex 05, France. E-mail: [email protected] 2Society for Southeast Asian Herpetology, Im Sand 3, D-69115 Heidelberg, Germany. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract The name-bearing type specimens of Trimeresurus monticola meridionalis Bourret, 1935 are shown to be composed of two primary syntypes that are referable to Ovophis monticola (Günther, 1864) as currently conceived, and a secondary syntype that belongs to Ovophis convictus (Stoliczka, 1870). Based on comparison of the three syntypes with other taxa of the Ovophis monticola-complex, historical analysis and a taxonomic review, we select one of the primary syntypes from northwestern Vietnam as the lectotype of T. monticola meridionalis Bourret, 1935 and fix the status of this taxon as a junior subjective synonym of Ovophis monticola. This position differs from the current synonymy of T. monticola meridionalis Bourret, 1935 with O. convictus. Key words: name-bearing types, Ovophis monticola, Ovophis convictus, snakes, taxonomy, Vietnam Introduction The systematics of the viperid snake Ovophis monticola (Günther, 1864) has been quite controversial. An analysis of its subspecific contents is detailed below. Recent authors such as Gumprecht et al. (2004) and Vogel (2006) agreed in dividing O. monticola into five subspecies. The complex of Ovophis monticola (Günther, 1864) was recently revised by Malhotra et al. -

Winter Activity of the Hime-Habu (Ovophis Okinavensis) in the Humid Subtropics: Foraging on Breeding Anurans at Low Temperatures

WINTER ACTIVITY OF THE HIME-HABU (OVOPHIS OKINAVENSIS) IN THE HUMID SUBTROPICS: FORAGING ON BREEDING ANURANS AT LOW TEMPERATURES AKIRA MORI1, MAMORU TODA1,3, AND HIDETOSHI OTA2 ABSTRACT: Snakes are ectothermic and rely on external heat sources to elevate their body temperature to levels required for various activities. Because of this constraint, snakes living at high latitudes and/or elevations cease their activity during cold weather, and in some cases exhibit physiological adaptations to the cold climate. Ovophis okinavensis is a small, nocturnal pitviper found in the subtropical region of the Ryukyu Archipelago, Japan, where the ambient temperature has a distinct seasonal fluctuation. We studied seasonal activity patterns, body temperatures, and food habits of O. okinavensis along a mountain stream from December 1996 to March 2000. Preliminary observations were also made with captive snakes to test the hypothesis that O. okinavensis has a physiological adaptation to efficiently digest prey at low temperatures. We found that O. okinavensis is most active at night during the cool season (from December to February), when two species of ranid frogs (Rana narina and_ R. okinavana) aggregate at a stream for reproduction. The body temperature of O. okinavensis ranged from 11.2 to 23.8°C (x = 16.1°C). Ninety-eight percent of the stomach contents consisted of frogs, and 37.0 % and 54.7 % were identified as R. narina and R. okinavana, respectively. The appearance of O. okinavensis coincided with breeding aggregations of these frogs, and extensive predation on the frogs by the snakes strongly suggests that winter activity in O. okinavensis at low body temperatures is associated with foraging. -

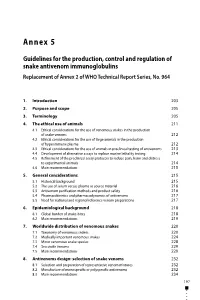

Guidelines for the Production, Control and Regulation of Snake Antivenom Immunoglobulins Replacement of Annex 2 of WHO Technical Report Series, No

Annex 5 Guidelines for the production, control and regulation of snake antivenom immunoglobulins Replacement of Annex 2 of WHO Technical Report Series, No. 964 1. Introduction 203 2. Purpose and scope 205 3. Terminology 205 4. The ethical use of animals 211 4.1 Ethical considerations for the use of venomous snakes in the production of snake venoms 212 4.2 Ethical considerations for the use of large animals in the production of hyperimmune plasma 212 4.3 Ethical considerations for the use of animals in preclinical testing of antivenoms 213 4.4 Development of alternative assays to replace murine lethality testing 214 4.5 Refinement of the preclinical assay protocols to reduce pain, harm and distress to experimental animals 214 4.6 Main recommendations 215 5. General considerations 215 5.1 Historical background 215 5.2 The use of serum versus plasma as source material 216 5.3 Antivenom purification methods and product safety 216 5.4 Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of antivenoms 217 5.5 Need for national and regional reference venom preparations 217 6. Epidemiological background 218 6.1 Global burden of snake-bites 218 6.2 Main recommendations 219 7. Worldwide distribution of venomous snakes 220 7.1 Taxonomy of venomous snakes 220 7.2 Medically important venomous snakes 224 7.3 Minor venomous snake species 228 7.4 Sea snake venoms 229 7.5 Main recommendations 229 8. Antivenoms design: selection of snake venoms 232 8.1 Selection and preparation of representative venom mixtures 232 8.2 Manufacture of monospecific or polyspecific antivenoms 232 8.3 Main recommendations 234 197 WHO Expert Committee on Biological Standardization Sixty-seventh report 9. -

A New Species of the Genus Trimeresurus from Southwest China (Squamata: Viperidae)

Asian Herpetological Research 2019, 10(1): 13–23 DOI: 10.16373/j.cnki.ahr.180062 ORIGINAL ARTICLE A New Species of the Genus Trimeresurus from Southwest China (Squamata: Viperidae) Zening CHEN1,2, Liang ZHANG3, Jingsong SHI4, Yezhong TANG1, Yuhong GUO5, Zhaobin SONG2 and Li DING1* 1 Chengdu Institute of Biology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Chengdu 610041, Sichuan, China 2 Key Laboratory of Bio-Resource and Eco-Environment of Ministry of Education, College of Life Sciences, Sichuan University, Chengdu 610065, Sichuan, China 3 Guangdong Key Laboratory of Animal Conservation and Resource Utilization, Guangdong Public Laboratory of Wild Animal Conservation and Utilization, Guangdong Institute of Applied Biological Resources, Guangzhou 510260, Guangdong, China 4 Key Laboratory of Vertebrate Evolution and Human Origins of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100044, China 5 School of Chemistry and Life sciences, Guizhou Education University, Guiyang 550018, Guizhou, China Abstract Species from the Trimeresurus popeiorum complex (Subgenus: Popeia) is a very complex group. T. popeiorum is the only Popeia species known from China. During the past two years, five adult Popeia specimens (4 males, 1 female) were collected from Yingjiang County, Southern Yunnan, China. Molecular, morphological and ecological data show distinct differences from known species, herein we describe these specimens as a new species Trimeresurus yingjiangensis sp. nov Chen, Ding, Shi -

A Review and Database of Snake Venom Proteomes

toxins Review A Review and Database of Snake Venom Proteomes Theo Tasoulis and Geoffrey K. Isbister * ID Clinical Toxicology Research Group, University of Newcastle, Newcastle 2298, Australia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +612-4921-1211 Academic Editor: Eivind Undheim Received: 1 September 2017; Accepted: 15 September 2017; Published: 18 September 2017 Abstract: Advances in the last decade combining transcriptomics with established proteomics methods have made possible rapid identification and quantification of protein families in snake venoms. Although over 100 studies have been published, the value of this information is increased when it is collated, allowing rapid assimilation and evaluation of evolutionary trends, geographical variation, and possible medical implications. This review brings together all compositional studies of snake venom proteomes published in the last decade. Compositional studies were identified for 132 snake species: 42 from 360 (12%) Elapidae (elapids), 20 from 101 (20%) Viperinae (true vipers), 65 from 239 (27%) Crotalinae (pit vipers), and five species of non-front-fanged snakes. Approximately 90% of their total venom composition consisted of eight protein families for elapids, 11 protein families for viperines and ten protein families for crotalines. There were four dominant protein families: phospholipase A2s (the most common across all front-fanged snakes), metalloproteases, serine proteases and three-finger toxins. There were six secondary protein families: cysteine-rich secretory proteins, L-amino acid oxidases, kunitz peptides, C-type lectins/snaclecs, disintegrins and natriuretic peptides. Elapid venoms contained mostly three-finger toxins and phospholipase A2s and viper venoms metalloproteases, phospholipase A2s and serine proteases. Although 63 protein families were identified, more than half were present in <5% of snake species studied and always in low abundance.