BROOKE-DISSERTATION-2015.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

5.3 Water Environment

5.3 Water Environment (1) Scarcity and Degradation of Freshwater in Egypt The water resources of Egypt could be divided into two systems; the Nile system and the groundwater system in desert area. The Nile system consisting of the Nile River, its branches, the irrigation canals, the agricultural drains and the valley and Delta aquifers. These water resources are interconnected. This system is replenished yearly with approximately 58.5 billion m3 of freshwater, as is given in the survey by MWRI. Egypt depends on the Nile for almost all of water resources; naturally, it is a crucial issue on how to preserve water quality of the River Nile. On the other hand, water in desert area is in deep sandstone aquifer and is generally non-renewable source, though considerable amounts of water are stored in the groundwater system. Table 5.13: Water Balance of the River Nile Water balance 3 Items (billion m /yr) Inflow Outflow & use HAD release 55.50 Effective rainfall 1.00 Sea water intrusion 2.00 Total inflow 58.50 Consumptive use agriculture 40.82 Consumptive use industries 0.91 Consumptive use domestic 0.45 Evaporation 3.00 Total use and evaporation 45.18 Navigation fresh water 0.26 Fayoum terminal drainage 0.65 Delta drainage to the sea 12.41 Total outflow 13.31 Source: MWRI Water demand in Egypt has been increasing due to population growth, higher standard of living, reclaiming new land, and advancing industrialization. Available water per capita per year for all purpose in 1999 was about 900m3; nonetheless, it is expected to fall to 670m3 and 536m3 by the years 2017 and 2025, respectively. -

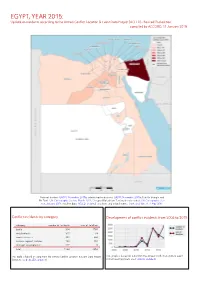

ACLED) - Revised 2Nd Edition Compiled by ACCORD, 11 January 2018

EGYPT, YEAR 2015: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) - Revised 2nd edition compiled by ACCORD, 11 January 2018 National borders: GADM, November 2015b; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015a; Hala’ib triangle and Bir Tawil: UN Cartographic Section, March 2012; Occupied Palestinian Territory border status: UN Cartographic Sec- tion, January 2004; incident data: ACLED, undated; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 Conflict incidents by category Development of conflict incidents from 2006 to 2015 category number of incidents sum of fatalities battle 314 1765 riots/protests 311 33 remote violence 309 644 violence against civilians 193 404 strategic developments 117 8 total 1244 2854 This table is based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project This graph is based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event (datasets used: ACLED, undated). Data Project (datasets used: ACLED, undated). EGYPT, YEAR 2015: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) - REVISED 2ND EDITION COMPILED BY ACCORD, 11 JANUARY 2018 LOCALIZATION OF CONFLICT INCIDENTS Note: The following list is an overview of the incident data included in the ACLED dataset. More details are available in the actual dataset (date, location data, event type, involved actors, information sources, etc.). In the following list, the names of event locations are taken from ACLED, while the administrative region names are taken from GADM data which serves as the basis for the map above. In Ad Daqahliyah, 18 incidents killing 4 people were reported. The following locations were affected: Al Mansurah, Bani Ebeid, Gamasa, Kom el Nour, Mit Salsil, Sursuq, Talkha. -

The Muslim 500 2011

The Muslim 500 � 2011 The Muslim The 500 The Muslim 500 � 2011 The Muslim The 500 The Muslim 500The The Muslim � 2011 500———————�——————— THE 500 MOST INFLUENTIAL MUSLIMS ———————�——————— � 2 011 � � THE 500 MOST � INFLUENTIAL MUSLIMS · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · All rights reserved. No part of this book may be repro- The Muslim 500: The 500 Most Influential Muslims duced or utilised in any form or by any means, electronic 2011 (First Edition) or mechanic, inclding photocopying or recording or by any ISBN: 978-9975-428-37-2 information storage and retrieval system, without the prior · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · written permission of the publisher. Views expressed in The Muslim 500 do not necessarily re- Chief Editor: Prof. S. Abdallah Schleifer flect those of RISSC or its advisory board. Researchers: Aftab Ahmed, Samir Ahmed, Zeinab Asfour, Photo of Abdul Hakim Murad provided courtesy of Aiysha Besim Bruncaj, Sulmaan Hanif, Lamya Al-Khraisha, and Malik. Mai Al-Khraisha Image Copyrights: #29 Bazuki Muhammad / Reuters (Page Designed & typeset by: Besim Bruncaj 75); #47 Wang zhou bj / AP (Page 84) Technical consultant: Simon Hart Calligraphy and ornaments throughout the book used courtesy of Irada (http://www.IradaArts.com). Special thanks to: Dr Joseph Lumbard, Amer Hamid, Sun- dus Kelani, Mohammad Husni Naghawai, and Basim Salim. English set in Garamond Premiere -

Water & Waste-Water Equipment & Works

Water & Waste-Water Equipment & Works Sector - Q3 2018 Report Water & Waste-Water Equipment & Works 3 (2018) Report American Chamber of Commerce in Egypt - Business Information Center 1 of 16 Water & Waste-Water Equipment & Works Sector - Q3 2018 Report Special Remarks The Water & Waste-Water Equipment & Works Q3 2018 report provides a comprehensive overview of the Water & List of sub-sectors Waste-Water Equipment & Works sector with focus on top tenders, big projects and important news. Irrigation & Drainage Canals Irrigation & Drainage Networks Tenders Section Potable Water & Waste-Water Pipelines Potable Water & Waste-Water Pumps - Integrated Jobs (Having a certain engineering component) - sorted by Water Desalination Stations - Generating Sector (the sector of the client who issued the tender and who would pay for the goods & services ordered) Water Wells Drilling - Client - Supply Jobs - Generating Sector - Client Non-Tenders Section - Business News - Projects Awards - Projects in Pre-Tendering Phase - Privatization and Investments - Published Co. Performance - Loans & Grants - Fairs and Exhibitions This report includes tenders with bid bond greater than L.E. 10,000 and valuable tenders without bid bond Tenders may be posted under more than one sub-sector Copyright Notice &RS\ULJKW$PHULFDQ&KDPEHURI&RPPHUFHLQ(J\SW $P&KDP $OOULJKWVUHVHUYHG1HLWKHUWKHFRQWHQWRIWKH7HQGHUV$OHUW6HUYLFH 7$6 QRUDQ\SDUWRILWPD\EHUHSURGXFHG sorted in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the American Chamber of Commerce in Egypt. In no event shall AmCham be liable for any special, indirect or consequential damages or any damages whatsoever resulting from loss of use, data or profits. -

1 Name: the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt Year of Origin: 1928 Founder

MUSLIM BROTHERHOOD IN EGYPT Name: The Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt Year of Origin: 1928 Founder(s): Hassan al-Banna Place(s) of Operation: Egypt Key Leaders: Acting: • Mahmoud Ezzat: Acting supreme guide • Mahmoud Hussein: Secretary-general • Mohamed Montasser: Spokesman • Talaat Fahmi: Spokesman • Mohamed Abdel Rahman: Head of the Higher Administrative Committee • Amr Darrag: Senior member and co-founder of the Freedom and Justice Party • Ahmed Abdel Rahman: Chairman of the Brotherhood’s Istanbul-based Office for Egyptians Abroad Imprisoned: • Mohammed Morsi: Imprisoned former president of Egypt; former leader of the Brotherhood’s Freedom and Justice Party • Mohammed Badie: Imprisoned supreme guide • Khairat el-Shater: Imprisoned deputy supreme guide • Mohamed Taha Wahdan: Imprisoned head of the Brotherhood’s Egypt-based Crisis Management Committee • Abdelrahman al-Barr: Imprisoned Brotherhood mufti and member of the Guidance Office [Image: source: Ikhwan Web] • Mahmoud Ghozlan: Imprisoned spokesman • Gehad al-Haddad: Imprisoned former spokesman and political activist Deceased: • Mohammed Kamal: Prominent Brotherhood member and head of the High Administrative Committee (deceased) [Image not available] Associated Organization(s): • Al-Ikhwan al-Muslimeen • Al-Ikhwan al-Muslimin • Gamaat al-Ikhwan al-Muslimin • Ikhwan • Muslim Brethren 1 MUSLIM BROTHERHOOD IN EGYPT • Muslim Brothers • Society of Muslim Brothers1 The Muslim Brotherhood (i.e., the Brotherhood) is Egypt’s oldest and largest Islamist organization.2 The Brotherhood rose to power -

Egyptian Labor Corps: Logistical Laborers in World War I and the 1919 Egyptian Revolution

EGYPTIAN LABOR CORPS: LOGISTICAL LABORERS IN WORLD WAR I AND THE 1919 EGYPTIAN REVOLUTION A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Kyle J. Anderson August 2017 © 2017 i EGYPTIAN LABOR CORPS: LOGISTICAL LABORERS IN WORLD WAR I AND THE 1919 EGYPTIAN REVOLUTION Kyle J. Anderson, Ph. D. Cornell University 2017 This is a history of World War I in Egypt. But it does not offer a military history focused on generals and officers as they strategized in grand halls or commanded their troops in battle. Rather, this dissertation follows the Egyptian workers and peasants who provided the labor that built and maintained the vast logistical network behind the front lines of the British war machine. These migrant laborers were organized into a new institution that redefined the relationship between state and society in colonial Egypt from the beginning of World War I until the end of the 1919 Egyptian Revolution: the “Egyptian Labor Corps” (ELC). I focus on these laborers, not only to document their experiences, but also to investigate the ways in which workers and peasants in Egypt were entangled with the broader global political economy. The ELC linked Egyptian workers and peasants into the global political economy by turning them into an important source of logistical laborers for the British Empire during World War I. The changes inherent in this transformation were imposed on the Egyptian countryside, but workers and peasants also played an important role in the process by creating new political imaginaries, influencing state policy, and fashioning new and increasingly violent repertoires of contentious politics to engage with the ELC. -

From Hasan Al-Banna to Mohammad Morsi; the Political Experience of Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt

FROM HASAN AL-BANNA TO MOHAMMAD MORSI; THE POLITICAL EXPERIENCE OF MUSLIM BROTHERHOOD IN EGYPT A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES OF MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY AHMET YUSUF ÖZDEMİR IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN MIDDLE EASTERN STUDIES JULY 2013 Approval of the Graduate School of Social Sciences Prof. Dr. Meliha Altunışık Director I certify that this thesis satisfies all the requirements as a thesis for the degree of Master of Science Assoc.Prof.Dr. Özlem Tür Head of Department This is to certify that we have read this thesis and that in our opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Science Prof. Dr. İhsan D. Dağı Supervisor Examining Committee Members Prof. Dr. Nuri Yurdusev (METU,IR) Prof. Dr. İhsan D. Dağı (METU, IR) Assis. Prof. Dr. Bayram Sinkaya (YBU, IR) I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. Name, Last name: Ahmet Yusuf Özdemir Signature : iii ABSTRACT FROM HASAN AL-BANNA TO MOHAMMAD MORSI; THE POLITICAL EXPERIENCE OF MUSLIM BROTHERHOOD IN EGYPT Özdemir, Ahmet Yusuf M.S. Program of Middle East Studies Supervisor: Prof. Dr. İhsan D. Dağı July 2013, 141 pages This thesis analyses the political and ideological transformation of the Society of Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt from its foundation in 1928 to 2012. -

An Analysis of the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood's Strategic Narrative

(Al-Ikhwan al-Muslimin) An Analysis of the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood's Strategic Narrative An Honors Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Elon University Honors Program By Kelsey L. Glover April, 2011 Approved by: Dr. Laura Rose le, Thesis Mentor Dr. Brooke Barnett, Communications (Reader) Dr. Tim Wardle, Religious Studies (Reader) AI-Ikhwan al-Muslimin An Analysis of the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood's Strategic Narrative Kelsey L. Glover (Dr. Laura Roselle) Department of International Studies-Elon University This study presents an in-depth qualitative analysis of the strategic narrative of the al Ikhwan al-Muslimin, also known as the Muslim Brotherhood of Egypt. The Muslim Brotherhood is a politically active Islamic organization and has been a formidable player on the political scene as one of the only opposition groups for over eighty years. Given the recent revolution in Egypt, they could have a dramatic impact on the future of the country, and it becomes even more important to understand their strategic narrative, how it has changed over time, and how it could change in the future. In order to analyze these narratives in a systematic manner, I developed a coding instrument to analyze the organization's narratives from the beginning of2008 to the end of2010. The coding instrument, Atlas.ti, was used to code for themes and descriptions of grievances and remedies. I analyzed these narratives to look for reactionary changes and trends over time. My research suggests that there has been a discemable shift in their narrative from their more radical beginnings to a moderate Islamist, pro-democracy movement today. -

Egyptian Presidents' Speeches in Times of Crisis: Comparative Analysis

American University in Cairo AUC Knowledge Fountain Theses and Dissertations 6-1-2015 Egyptian presidents' speeches in times of crisis: Comparative analysis Dina Tawfic Abdel attahF Follow this and additional works at: https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds Recommended Citation APA Citation Abdel Fattah, D. (2015).Egyptian presidents' speeches in times of crisis: Comparative analysis [Master’s thesis, the American University in Cairo]. AUC Knowledge Fountain. https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds/1330 MLA Citation Abdel Fattah, Dina Tawfic. Egyptian presidents' speeches in times of crisis: Comparative analysis. 2015. American University in Cairo, Master's thesis. AUC Knowledge Fountain. https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds/1330 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by AUC Knowledge Fountain. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of AUC Knowledge Fountain. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Chapter 1. Introduction In recent years, presidential speech has elicited comprehensive studies, with scholars using different terms to describe the process by which politicians influence the public. Some scholars tend to call the process of the president— public communication, an act of persuasion rather than manipulation. For example, Mutz, Sniderman, and Brody (1999) consider this process "a legitimate feature of political discourse" (p.437) because politics is about struggle for power, and language is a dynamic tool in the political process. However, other scholars underscore that there is always an attempt to exploit political language to manipulate facts, influence people, and change their minds to gain their support. Emeren (2005, p. xiii) claims that speech “boils down to intentionally deceiving one's addressee.” During periods of crisis, on the one hand, presidents intend to hide their failures at managing the crisis to win people's support. -

Authoritarianism, Uncertainty, and Prospects for Change

10 Authoritarianism, Uncertainty, and Prospects for Change The Arab world is unique in the prevalence of long-lived, undemocratic regimes consisting largely of monarchies exhibiting varying degrees of lib- eralism and authoritarian states applying repression of varying intensities. These governments face rising internal demands for political liberalization. The period 2005–06 witnessed an “Arab Spring” illustrated by general elec- tions in Iraq, Lebanon, and the Palestinian Authority; municipal elections in Saudi Arabia; women’s candidacies in Kuwait; and the establishment of a truth and reconciliation commission in Morocco, among other develop- ments. This flowering was followed by retrenchments in Egypt, Syria, and a number of other Arab countries. This “two steps forward, one step back” pattern is consistent with quantitative modeling of political regime scoring systems such as those of the Polity IV Project or Freedom House, which can be used to calculate the timing and magnitude of political change. As dis- cussed in detail in appendix 10A, these models point to rising (though non- monotonic) odds on the probability of liberalizing transitions as illustrated in figure 10.1, derived from a fairly standard model from this genre.1 1. Such episodes are typically defined as a three-point or more positive (though not neces- sarily irreversible) change in the democracy score over a period of three years or less, at any given point in time. Examples of such liberalizing episodes in the sample would include Spain’s transition from the Franco regime to parliamentary democracy in 1975, the 1985 end of military rule in Brazil, South Korea’s transition to civilian government in 1987, the 1989–90 collapse of the Ceau¸sescu regime and the beginning of democracy in Romania, and South Africa’s postapartheid transition during 1992–94. -

A Discursive Analysis of the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood Balancing Act, from the Authoritarian Era to the Arab Spring

AN EDUCATION IN PRUDENCE: A DISCURSIVE ANALYSIS OF THE EGYPTIAN MUSLIM BROTHERHOOD BALANCING ACT, FROM THE AUTHORITARIAN ERA TO THE ARAB SPRING Major Derek Prohar JCSP 38 PCEMI 38 Master of Defence Studies Maîtrise en études de la défense Disclaimer Avertissement Opinions expressed remain those of the author and do Les opinons exprimées n’engagent que leurs auteurs et not represent Department of National Defence or ne reflètent aucunement des politiques du Ministère de Canadian Forces policy. This paper may not be used la Défense nationale ou des Forces canadiennes. Ce without written permission. papier ne peut être reproduit sans autorisation écrite. © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, as represented by the © Sa Majesté la Reine du Chef du Canada, représentée par le Minister of National Defence, 2012 ministre de la Défense nationale, 2012. CANADIAN FORCES COLLEGE - COLLÈGE DES FORCES CANADIENNES JCSP 38 - PCEMI 38 MASTER OF DEFENCE STUDIES - MAITRISE EN ÉTUDES DE LA DÉFENSE An Education in Prudence: A Discursive Analysis of the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood Balancing Act, from the Authoritarian Era to the Arab Spring By Major Derek Prohar This paper was written by a student attending La présente étude a été rédigée par un stagiaire the Canadian Forces College in fulfilment of one du Collège des Forces canadiennes pour of the requirements of the Course of Studies. satisfaire à l'une des exigences du cours. L'étude The paper is a scholastic document, and thus est un document qui se rapporte au cours et contains facts and opinions, which the author contient donc des faits et des opinions que seul alone considered appropriate and correct for l'auteur considère appropriés et convenables au the subject. -

Discharge from Municipal Wastewater Treatment Plants Into Rivers Flowing Into the Mediterranean Sea

UNEP(DEPI)/MED WG. 334/Inf.4/Rev.1 15 May 2009 ENGLISH MEDITERRANEAN ACTION PLAN MED POL Meeting of MED POL Focal Points Kalamata (Greece), 2- 4 June 2009 DISCHARGE FROM MUNICIPAL WASTEWATER TREATMENT PLANTS INTO RIVERS FLOWING INTO THE MEDITERRANEAN SEA UNEP/MAP Athens, 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE .................................................................................................................................1 PART I.......................................................................................................................................3 1. ΑΒOUT THE STUDY............................................................................................................... 3 1.1 Historical Background of the Study .....................................................................................3 1.2 Report on the Municipal Wastewater Treatment Plants in the Mediterranean Coastal Cities .........................................................................................................................................4 1.3 Methodology and Procedures of the present Study ............................................................5 2. MUNICIPAL WASTEWATER IN THE MEDITERRANEAN..................................................... 8 2.1 Characteristics of Municipal Wastewater in the Mediterranean ..........................................8 2.2 Impacts of Nutrients ............................................................................................................9 2.3 Impacts of Pathogens..........................................................................................................9