Towards a Just and Lasting Change

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Study on Human Rights Violation of Tangkhul Community in Ukhrul District, Manipur

A STUDY ON HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATION OF TANGKHUL COMMUNITY IN UKHRUL DISTRICT, MANIPUR. A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE TILAK MAHARASHTRA VIDYAPEETH, PUNE FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN SOCIAL WORK UNDER THE BOARD OF SOCIAL WORK STUDIES BY DEPEND KAZINGMEI PRN. 15514002238 UNDER THE GUIDANCE OF DR. G. R. RATHOD DIRECTOR, SOCIAL SCIENCE CENTRE, BVDU, PUNE SEPTEMBER 2019 DECLARATION I, DEPEND KAZINGMEI, declare that the Ph.D thesis entitled “A Study on Human Rights Violation of Tangkhul Community in Ukhrul District, Manipur.” is the original research work carried by me under the guidance of Dr. G.R. Rathod, Director of Social Science Centre, Bharati Vidyapeeth University, Pune, for the award of Ph.D degree in Social Work of the Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth, Pune. I hereby declare that the said research work has not submitted previously for the award of any Degree or Diploma in any other University or Examination body in India or abroad. Place: Pune Mr. Depend Kazingmei Date: Research Student i CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the thesis entitled, “A Study on Human Rights Violation of Tangkhul Community in Ukhrul District, Manipur”, which is being submitted herewith for the award of the Degree of Ph.D in Social Work of Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth, Pune is the result of original research work completed by Mr. Depend Kazingmei under my supervision and guidance. To the best of my knowledge and belief the work incorporated in this thesis has not formed the basis for the award of any Degree or similar title of this or any other University or examining body. -

"Iloi+L'ua. T"Rr., Lio.O7z7oo7z013 Ac(Pwc), Dated- The. 28Th-February' 2014 Or

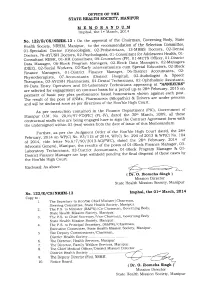

OFFICE OF THE STATE HEALTH SOCIETY' MANIPUR MEMORANDUM ImPhal, the l* March, 201'1 No. 122/E/CS/NRHM- 13 : On the approval of the Chairman, Governing Body, State tlealth Society, NRHM, Manipur, to the recommendation of the Selection Committee' 13 MBBS 02-Denta'1 01 SpecieilistDoctor lGynecologistl, 02 Pediatricians, .Doctors' Doctors,76-AYUSH Doctors, 02 Psychologists,0I-Consultant for AdolescentHealth' 01 Distrrct Consultant RBSK, O1-HR Consultant, og-Counselors(FP), 01-MCTS Officer' 01 Data Manager, o.r_Block Program Managers, o2-Block Data Managers' 02-Managers 02 Biock OZ-So"ir-fWorkers,02-Early interventjonists cum Special Educators' 1nfnO), 02- iinance Maiag..", 0l-Distnct i''inzLnce Manager, 06 District Accountants' & Speech PhysiotherapistJ, 07 Accountants (Distict Hospital), O2-Audiologlst Assrstants' Therapists,bZ AyUStt Pharmacists, 04 Dental Technicians' 02 Ophthalmic at OS n.lu n"ttf C)perators and 05 Laboratory Technicians appearing- "ANNEXURE" Februa-ry' 2015 on are selected lor engagement on conlract basis for a period up-to 28th "p"v post U^"t. plus performance based honorarium sho\r'n agalnst each """-""i under process ii'. .".t"ft"f ot ttte poir of nN'us, pnarmacisrs (Aliopathicl & Drivers ale and will be declared soon as per directives of the Honble High Court (PIC)' Governlnent of As per instruction contained in the FinancreDepartment March 2009' all these M"rip;;6.M. No. 2016197 FD(Pic) (Pt.lv), dated the 30d Agrcement form \&'rth contractua.l staifs who are belng en8aged have to sign the Contl act Memorandum- the undersigned within 02 (t\\'o) t..''a" ftorrl lhe date of lssuc of thls llonbte High Court dated' the 28ih Further, as Per the Judgment Ordcr of the & WPIC)No 104 n.rr.".ry, iOii or''We1C1No. -

Sl. No. Segment Name Name of the Selected Candidates

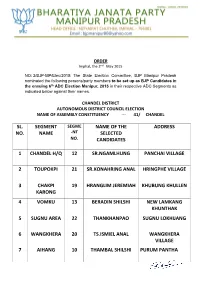

ORDER Imphal, the 2nd May 2015 NO: 2/BJP-MP/Elec/2015: The State Election Committee, BJP Manipur Pradesh nominated the following persons/party members to be set up as BJP Candidates in the ensuing 6th ADC Election Manipur, 2015 in their respective ADC Segments as indicated below against their names. CHANDEL DISTRICT AUTONOMOUS DISTRICT COUNCIL ELECTION NAME OF ASSEMBLY CONSTITUENCY --- 41/ CHANDEL SL. SEGMENT SEGME NAME OF THE ADDRESS NO. NAME -NT SELECTED NO. CANDIDATES 1 CHANDEL H/Q 12 SR.NGAMLHUNG PANCHAI VILLAGE 2 TOUPOKPI 21 SR.KONAHRING ANAL HRINGPHE VILLAGE 3 CHAKPI 19 HRANGLIM JEREMIAH KHUBUNG KHULLEN KARONG 4 VOMKU 13 BERADIN SHILSHI NEW LAMKANG KHUNTHAK 5 SUGNU AREA 22 THANKHANPAO SUGNU LOKHIJANG 6 WANGKHERA 20 TS.ISMIEL ANAL WANGKHERA VILLAGE 7 AIHANG 10 THAMBAL SHILSHI PURUM PANTHA 8 PANTHA 11 H.ANGTIN MONSANG JAPHOU VILLAGE 9 SAJIK TAMPAK 23 THANGSUANKAP GELNGAI VILAAGE 10 TOLBUNG 24 THANGKHOMANG AIBOL JOUPI VILLAGE HAOKIP CHANDEL DISTRICT AUTONOMOUS DISTRICT COUNCIL ELECTION NAME OF ASSEMBLY CONSTITUENCY --- 42/ TENGNOUPAL SL. SEGMENT SEGME NAME OF THE ADDRESS NO. NAME -NT SELECTED NO. CANDIDATES 1 KOMLATHABI 8 NG.KOSHING MAYON KOMLATHABI VILLAGE 2 MACHI 2 SK.KOTHIL MACHI VILLAGE, MACHI BLOCK 3 RILRAM 5 K.PRAKASH LANGKHONGCHING VILLAGE 4 MOREH 17 LAMTHANG HAOKIP UKHRUL DISTRICT AUTONOMOUS DISTRICT COUNCIL ELECTION NAME OF ASSEMBLY CONSTITUENCY --- 43/ PHUNGYAR SL. SEGMENT SEGME NAME OF THE ADDRESS NO. NAME -NT SELECTED NO. CANDIDATES 1 GRIHANG 19 SAUL DUIDAND GRIHANG VILLAGE KAMJONG 2 SHINGKAP 21 HENRY W. KEISHING TANGKHUL HUNDUNG 3 KAMJONG 18 C.HOPINGSON KAMJONG BUNGPA KHULLEN 4 CHAITRIC 17 KS.GRACESON SOMI PUSHING VILLAGE 5 PHUNGYAR 20 A. -

The Impact of English Language on Tangkhul Literacy

THE IMPACT OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE ON TANGKHUL LITERACY A THESIS SUBMITTED TO TILAK MAHARASHTRA VIDYAPEETH, PUNE FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (Ph.D.) IN ENGLISH BY ROBERT SHIMRAY UNDER THE GUIDANCE OF Dr. GAUTAMI PAWAR UNDER THE BOARD OF ARTS & FINEARTS STUDIES MARCH, 2016 DECLARATION I hereby declare that the thesis entitled “The Impact of English Language on Tangkhul Literacy” completed by me has not previously been formed as the basis for the award of any Degree or other similar title upon me of this or any other Vidyapeeth or examining body. Place: Robert Shimray Date: (Research Student) I CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the thesis entitled “The Impact of English Language on Tangkhul Literacy” which is being submitted herewith for the award of the degree of Vidyavachaspati (Ph.D.) in English of Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth, Pune is the result of original research work completed by Robert Shimray under my supervision and guidance. To the best of my knowledge and belief the work incorporated in this thesis has not formed the basis for the award of any Degree or similar title or any University or examining body upon him. Place: Dr. Gautami Pawar Date: (Research Guide) II ACKNOWLEDGEMENT First of all, having answered my prayer, I would like to thank the Almighty God for the privilege and opportunity of enlightening me to do this research work to its completion and accomplishment. Having chosen Rev. William Pettigrew to be His vessel as an ambassador to foreign land, especially to the Tangkhul Naga community, bringing the enlightenment of the ever lasting gospel of love and salvation to mankind, today, though he no longer dwells amongst us, yet his true immortal spirit of love and sacrifice linger. -

CDL-1, UKL-1, SNP-1 Sl. No. Form No. Name Address District Catego Ry Status Recommendation of the Screening Commit

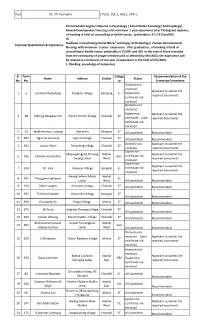

Post A1: STI Counselor 3 Posts: CDL-1, UKL-1, SNP-1 Post Graduate degree I diploma in Psychology / Social Work/ Sociology/ Anthropology/ Human Development/ Nursing; with minimum 1 year experience after PG degree/ diploma, of working in field of counselling in health sector; preferably in STI / RTI and HIV. Or Graduate in Psychology/Social Work/ Sociology/ Anthropology/ Human Development/ Essential Qualification & Experience: Nursing; with minimum 3 years .experience after graduation, of working in field of counselling in health sector; preferably in STI/RTI and HIV. In the case of those recruited from the community of people infected with or affected by HIV/AIDS, the experience will be relaxed to a minimum of one year of experience in the field of HIV/AIDS. 1. Working knowledge of computers Sl. Form Catego Recommendation of the Name Address District Status No. No. ry Screening Committee Domicile not enclosed, Applicant to submit the 1 2 Lanmila Khapudang Kongkan Village Kamjong ST Experience required documents certificate not enclosed Domicile not enclosed, Experience Applicant to submit the 2 38 Dilbung Rengwar Eric Purum Pantha Village Chandel ST certificate , Caste required documents certificate not enclosed 3 54 Makhreluibou Luikang Makhrelu Senapati ST All submitted Recommended 4 483 Ngorum Kennedy Japhou Village Chandel ST All submitted Recommended Domicile not Applicant to submit the 5 564 Jacinta Telen Penaching Village Chandel ST enclosed required documents Experience Mayanglangjing Tamang Imphal Applicant to submit the 6 756 -

![163 [27 July, 2017] Written Answers to Unstarred Questions and Uts To](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7178/163-27-july-2017-written-answers-to-unstarred-questions-and-uts-to-1107178.webp)

163 [27 July, 2017] Written Answers to Unstarred Questions and Uts To

Written Answers to[27 July, 2017] Unstarred Questions 163 and UTs to examine the status of Aanganwadi Centres (AWCs) for convergence of existing facilities available in Aanganwadi Centres vis-a-vis the infrastructure available in the primary schools in State and UTs for preparing children for better transition and school readiness. Currently Early Childhood Care and Education (ECCE) is one of the six free services provided through Aanganwadi Centre (AWCs) under the Integrated Child Development Service (ICDS) Scheme being implemented by Ministry of Women and Child Development. At present, there are 3.53 crore children in the age group 3-6 years who are beneficiaries of pre-school education in Aanganwadi Centre under ICDS. The ICDS is a universal self-selecting scheme available to all the beneficiaries who enroll at the AWCs. Funds under various Schemes for Manipur 1344. SHRI K. BHABANANDA SINGH: Will the Minister of HUMAN RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT be pleased to state: (a) the details of funds under the Sarva Shiksha Abhiyaan (SSA), the Rashtriya Madhyamik Shiksha Abhiyaan (RMSA) and the Rashtriya Uchchatar Shiksha Abhiyan (RUSA) released to Manipur during the last three years, district- wise and year-wise; (b) the names of schools and colleges constructed and the number of teachers appointed under those schemes; (c) the details of funding, district-wise; (d) whether teachers under the schemes get salaries at the end of months together and if so, the reasons therefor; and (e) whether proxy teachers work in many schools in the State and if so, the steps taken to prevent it? THE MINISTER OF STATE IN THE MINISTRY OF HUMAN RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT (SHRI UPENDRA KUSHWAHA): (a) to (c) The details on funds released by the Government of India under the Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan (SSA), the Rashtriya Madhyamik Shiksha Abhiyan (RMSA) and the Rashtriya Uchchatar Shiksha Abhiyan (RUSA) to Government of Manipur during the last three years are as under:– 164Written Answers to [RAJYA SABHA] Unstarred Questions (` in lakh) Sl. -

APPEAL the Importance of Education in the Development of the Individual

APPEAL The importance of Education in the development of the individual in particular and society/economy in general, is an undeniable fact. With the change in the social set-up and emergence of Information Technology in the modern age, the need to review the system of Education has become necessary. Also, adequate environment for proper development of the students on one hand, and on the other to enable teachers to impart knowledge using modern methods/techniques in educational institution, is a requirement which has to be ensured by conducting studies on the existing institutions. This will provide an insight on the adequacy/shortfalls. As an endeavour towards this end, the Directorate of Economics & Statistics, Manipur as an authorized agency for statistical activities in the State of Manipur, is conducting the present survey on Private Schools as the first phase to build a database on the various aspects of Education in the Private sector in Manipur. The data collected will not be used, disclosed or retain to any third/other parties except for the purpose of generation of data base at the macro level. The Primary Investigators of this Directorate will be visiting all the Private Schools in Manipur for collection of the information through the schedule ‘Collection of information on Private Educational Institutions in Manipur, 2015’. Your valuable cooperation in providing the information as per the schedule will go a long way to enable the Directorate in generating data depicting the status of the Private Educational Institutions in -

E-BOOK I Follow Us Online

E-BOOK I Follow us online: Aram.Academy.IAS aramias_academy aram_ias_academy aimcivilservices aramiasacademy.com "ROLL CALL - PRELIMS 2020” Join our Aim Civils IMPORTANT Telegram Channel CURRENT AFFAIRS ON https://t.me/aimcivilservices HISTORY FOR PRELIMS 2020 TO ACCESS EVERYDAY CURRENT AFFAIRS IN THE PERSPECTIVE OF PRELIMS AND MAINS. TO ACCESS REGULAR RESOURCE MATERIALS Join our ARAM IAS TownHall Telegram Group https://t.me/aramtownhall FOR FACULTY INTERACTION TO ATTEND DAY TO DAY QUIZ Contents 1. MP’s Orchha Town added to UNESCO WHS Tentave List 2. India & Portugal to set up Naonal Marime Heritage Museum 3. ASI declares Chaukhandi Stupa as Monument of Naonal Importance 4. Leh celebrates Sindhu Darshan Fesval 5. Japan gis Manipur a Peace Museum built on WWII memories 6. Iraq’s Babylon listed as UNESCO’s World Heritage Site 7. Jaipur listed as UNESCO World Heritage Site 8. Naonal Museum of Indian Cinema’s news bullen launched 9. Odisha Rasagola’ gets GI Tag 10. Shawala Teja Singh temple in Pakistan opened for Hindus aer 72 Years 11. Indus Valley inscripons were wrien logographically : Research 12. Virasat-e-Khalsa set to enter Asia Book of Records 13. Tamil Nadu’s Panchamirtham prasadam granted GI tag 14. Naonal Tribal Fesval ‘Aadi Mahotsav’ being organised at Leh-Ladakh 15. ‘Namaste Pacific’ Cultural Event held in New Delhi 16. UNESCO to publish Guru Nanak Dev’s wring in world languages 17. Ladakhi Shondol dance enters Guinness book of world record 18. Shirui Lily Fesval: Manipur 19. CCRT e-portal and YouTube Channel inaugurated 20. First - ever Ladakh Literature Fesval 21. -

District Report UKHRUL

Baseline Survey of Minority Concentrated Districts District Report UKHRUL Study Commissioned by Ministry of Minority Affairs Government of India Study Conducted by Omeo Kumar Das Institute of Social Change and Development: Guwahati VIP Road, Upper Hengerabari, Guwahati 781036 1 ommissioned by the Ministry of Minority CAffairs, this Baseline Survey was planned for 90 minority concentrated districts (MCDs) identified by the Government of India across the country, and the Indian Council of Social Science Research (ICSSR), New Delhi coordinates the entire survey. Omeo Kumar Das Institute of Social Change and Development, Guwahati has been assigned to carry out the Survey for four states of the Northeast, namely Assam, Arunachal Pradesh, Meghalaya and Manipur. This report contains the results of the survey for Ukhrul district of Manipur. The help and support received at various stages from the villagers, government officials and all other individuals are most gratefully acknowledged. ■ Omeo Kumar Das Institute of Social Change and Development is an autonomous research institute of the ICSSR, New delhi and Government of Assam. 2 CONTENTS BACKGROUND....................................................................................................................................8 METHODOLOGY.................................................................................................................................9 TOOLS USED ......................................................................................................................................10 -

16 October Page 1

Evening daily Imphal Times Regd.No. MANENG /2013/51092 Volume 7, Issue 78,3 Wednesday, October 16, 2019 Maliyapham Palcha kumsing 3417 Rs. 2/- NTC appeals all negotiators to be MPSC Raw : Fate of many youths in dire magnanimous; straight due to erroneous system CFMG-NSCN (I-M) discuss IT News in state that commands huge cases by a totally different all this, another point Imphal, Oct 16 respect and corresponding signature; tabulation sheet worth noting is that the accountability. It is found signing only by the then Chairman was due to ceasefire rules With the case to the alleged unfortunate that so many Chairman and no one else; are retire on 7 th November, Agency population integration”. As ceasefire violations that irregularities to the selection controversies have come up some of the irregularities 2017. Without going into Dimapur, Oct 16 and when Nagas attained crop up between NSCN (I- of candidates being in this examination .The mentioned in the enquiry the merits of the sovereignty and M) and security forces. reserved by the Manipur findings of the enquiry report. In addition to these, allegations, the fact that Stating that it had high integration, there would be They were very positive. High Court, fate of many committee constituted by the there was no Head Examiner, such illegalities and hope that years of political demographic changes, but Except for minor ceasefire youths are in dire straight order of the Manipur High o evaluation guidelines, no irregularities took place in negotiations between till then the State of violations, they have kept due to the erroneous Court is in public domain and Model answer paper as per the conduct of such a Government of India and Nagaland would remain as peace,” said Chauhan, system which went it has concluded that there RTI information. -

09 Chapter 4.Pdf

- 73 - Chapter Four Research Setting (Manipur – A land of Jewels) Manipur is a state in Northeastern India, with the city of Imphal as its capital. Manipur consist of Meitei, Pangal, Naga, Zomi, Kuki and Mizo people, and is bounded by the Indian states of Nagaland to the north, Mizoram to the south, and Assam to the west; it also borders Burma to the east. It covers an area of 22,347 square kilometres (8,628 sq mi). Manipur, as the name suggests, is a land of jewels. Its rich culture excels in every aspect as in martial arts, dance, theatre and sculpture. The charm of the place is the greenery with the moderate climate making it a tourists' heaven. Taking into account the state's geographical location, Manipur can serve as the India's Gateway to the South-East Asia. The proposed Trans-Asian Railway Network (TARN) if constructed will pass on from Manipur, connecting India to Burma, Thailand, Malaysia and Singapore. As such, economists suggest that Manipur could transform into a bustling economic powerhouse state in the next couple of decades. The Meiteis (Meeteis), who live primarily in the state's valley region, form the primary ethnic group (60% of the total population) but occupy only 10% of the total land area. Their language, Meiteilon (Meeteilon), (also known as Manipuri ), is also the lingua franca in the state, and was recognized as one of the national languages of India in 1992. The Muslims (Meitei-Pangal) also live in the valley; the Kukis, Nagas, Zomis and other smaller groups form about 40% of the population but occupy the remaining 90% of the total land area of Manipur. -

Mining Without Consent

ISSN (Online) - 2349-8846 Mining Without Consent Chromite Mining in Manipur FRANKY VARAH Vol. 49, Issue No. 25, 21 Jun, 2014 Franky Varah ([email protected]) is a doctoral scholar at the Centre for Studies in Science Policy, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. The recent identification of chromite deposits in two districts of Manipur, Ukhrul and Chandel, has led the government to grant mining clearances disregarding constitutional provisions. While environmental degradation and tribal displacement due to chromite mining in Odisha is well documented, the administration is yet to learn from Odisha’s mistakes. Chromite is a versatile element that is used in metallurgical, refractory, chemical and non- ferrous alloy industries. Owing to its multiple uses, chromite is a valuable and strategic raw material. Most of the chromite resources in the world are located in South Africa, that contributes to more than 50% of the world-trade in chromite (Pariser: 2013), and Kazakhstan. In India, more than 93% of chromite deposits are located in Odisha, mainly in the Sukinda valley in Cuttack and Jajpur districts (IBM: 2012). The world production of chromite increased from 23.5 million tonnes in 2009 to 30 million tonnes in 2010 (IBM: 2012). The production of chromite from Indian mines registered a 24% increase in 2010-11 compared to 2009-10 (IBM: 2012). India accounts for 17% of the world production of chromite, making it a significant exporter of the mineral (USGS: 2011). The Indian Bureau of Mines 2013 report indicated that Manipur has 6.66 MT (3% of total chromite reserves in India) chromite resources of ophiolite belt in Ukhrul (5.5 MT) and Chandel (1.1 MT) districts (IBM: 2013).