Dickason Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pretty Little Liars Pretty Little Liars

Pretty Little Liars Pretty Little Liars Pretty Little Liars Pretty Little Liars Three may keep a secret, if two of them are dead. Benjamin Franklin How It All Started Imagine it’s a couple of years ago, the summer between seventh and eighth grade. You’re tan from lying out next to your rock-lined pool, you’ve got on your new Juicy sweats (remember when everybody wore those?), and your mind’s on your crush, the boy who goes to that other prep school whose name we won’t mention and who folds jeans at Abercrombie in the mall. You’re eating your Cocoa Krispies just how you like ’em – doused in skim milk – and you see this girl’s face on the side of the milk carton. MISSING. She’s cute – probably cuter than you – and has a feisty look in her eyes. You think, Hmm, maybe she likes soggy Cocoa Krispies too. And you bet she’d think Abercrombie boy was a hottie as well. You wonder how someone so . well, so much like you went missing. You thought only girls who entered beauty pageants ended up on the sides of milk cartons. Well, think again. Aria Montgomery burrowed her face in her best friend Alison DiLaurentis’s lawn. ‘Delicious,’ she murmured. ‘Are you smelling the grass?’ Emily Fields called from behind her, pushing the door of her mom’s Volvo wagon closed with her long, freckly arm. ‘It smells good.’ Aria brushed away her pink-striped hair and breathed in the warm early-evening air. ‘Like summer.’ Emily waved ’bye to her mom and pulled up the blah jeans that were hanging on her skinny hips. -

Radio Advertising

The Michigan International Women’s Show, known as a premier women’s event in the greater Detroit area, was widely embraced by the market. TOTAL AD CAMPAIGN $430,505 PR IMPRESSIONS 43,900,197 NUMBER OF EXHIBIT SPACES 548 ATTENDANCE 32,000+ women OVERVIEW SCENES FROM THE SHOW The 22nd annual show attracted MOTHERS, DAUGHTERS, GIRLFRIENDS AND CO-WORKERS who packed the aisles throughout the four day event. Our show surveys indicated that women came to the show to shop, attend cooking demonstrations and sample food, watch fashion shows and stage presentations, register for promotions and prizes, get health screenings, meet celebrity guests, and have fun. DEMOGRAPHICS Olympic Gold Medalist Keegan Allen Princess Tea Laurie Hernandez from Pretty Little Liars Firefighter Fashion Shows Mother Daughter Look Alike Throughout the four days, exciting and educational activities were held on three different stages. The stages featured CELEBRITY guests, innovative COOKING programs, MUSICAL entertainment, FASHION shows and more – all designed to attract, captivate and entertain the target audience. FEATURES & PROMOTIONS A comprehensive marketing and advertising campaign promoted the show for three weeks through TELEVISION, RADIO, PRINT and numerous DIGITAL PLATFORMS as well as SOCIAL MEDIA and GRASSROOTS MARKETING initiatives. The show was promoted with signage in 110 Walgreens stores and hundreds of retail locations, increasing sponsor awareness in high traffic locations, as well as media contesting and promotions. ADVERTISING EXPOSURE The Michigan International Women’s Show received comprehensive television coverage and exposure. In addition to a two week paid schedule on three network stations, the show’s extended reach was enhanced through promotions, contests and live shots. -

Teen-Noir – Veronica Mars Og Den Moderne Ungdomsserie (PDF)

Teen Noir – Veronica Mars og den moderne ungdomsserie AF MICHAEL HØJER I 2004 havde den amerikanske ungdomskanal UPN premiere på Rob Tho- mas’ ungdomsserie Veronica Mars (2004-2007). Serien foregår i den fikti- ve, sydcaliforniske by Neptune og handler om teenagepigen Veronica Mars (Kristen Bell), der arbejder som privatdetektiv, samtidig med at hun går på high school. Trods det faktum, at Veronica Mars havde en dedikeret fanskare bag sig, befandt den sig i samtlige tre sæsoner blandt de mindst sete tv-serier i USA. Da tendensen kun forværredes hen mod afslutningen af tredje sæ- son, var der ikke længere økonomisk grobund for at fortsætte (Van De Kamp 2007). Serien blev sat på pause, inden de sidste fem afsnit blev vist, hvor- efter CW (en fusion af det tidligere UPN og en anden ungdomsorienteret ka- nal ved navn WB) lukkede permanent for kassen. Selvom seriens hardcore fans sendte 10.000 Marsbarer til CW’s hovedkontor i et forsøg på at genop- live serien, og selvom der var flere forsøg fra produktionsholdets side på at fortsætte den enten via tv, en opfølgende film eller endda en tegneserie, er dvd-udgivelsen af Veronica Mars’ tre sæsoner det sidste, man har set til Rob Thomas’ serie. Foruden sin dedikerede fanskare – der bl.a. talte prominente personer som forfatteren Stephen King, filminstruktøren Kevin Smith og Joss Whe- don, der skabte både Firefly og Buffy the Vampire Slayer (UPN/WB, 1997- 2003)1 – var også anmelderne hurtige til at se seriens kvaliteter. Specielt de første to sæsoner af Veronica Mars blev meget vel modtaget. Større, to- neangivende amerikanske medier som LA Weekly, The Village Voice, New York Times og Time roste alle serien med ord som ”remarkably innovative”, ”promising”, ”smart, engaging” og ”genre-defying”. -

Prettylittleliars: How Hashtags Drive the Social TV Phenomenon

Salve Regina University Digital Commons @ Salve Regina Pell Scholars and Senior Theses Salve's Dissertations and Theses Summer 6-2013 #PrettyLittleLiars: How Hashtags Drive The Social TV Phenomenon Melanie Brozek Salve Regina University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.salve.edu/pell_theses Part of the American Popular Culture Commons, Film and Media Studies Commons, and the Television Commons Brozek, Melanie, "#PrettyLittleLiars: How Hashtags Drive The Social TV Phenomenon" (2013). Pell Scholars and Senior Theses. 93. https://digitalcommons.salve.edu/pell_theses/93 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Salve's Dissertations and Theses at Digital Commons @ Salve Regina. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pell Scholars and Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Salve Regina. For more information, please contact [email protected]. #PrettyLittleLiars: How Hashtags Drive The Social TV Phenomenon By Melanie Brozek Prepared for Dr. Esch English Department Salve Regina University May 10, 2013 Brozek 2 #PrettyLittleLiars: How Hashtags Drive The Social TV Phenomenon ABSTRACT: Twitter is used by many TV shows to promote discussion and encourage viewer loyalty. Most successfully, ABC Family uses Twitter to promote the teen drama Pretty Little Liars through the use of hashtags and celebrity interactions. This study analyzes Pretty Little Liars’ use of hashtags created by the network and by actors from the show. It examines how the Pretty Little Liars’ official accounts engage fans about their opinions on the show and encourage further discussion. Fans use the network- generated hashtags within their tweets to react to particular scenes and to hopefully be noticed by managers of official show accounts. -

Tick-Tock, B**Ches”

CREATED BY I. Marlene King BASED ON THE BOOKS BY Sara Shepard EPISODE 7.01 “Tick-Tock, B**ches” In a desperate race to save one of their own, the girls must decide whether to hand over evidence of Charlotte's real murderer to "Uber A." WRITTEN BY: I. Marlene King DIRECTED BY: Ron Lagomarsino ORIGINAL BROADCAST: June 21, 2016 NOTE: This is a transcription of the spoken dialogue and audio, with time-code reference, provided without cost by 8FLiX.com for your entertainment, convenience, and study. This version may not be exactly as written in the original script; however, the intellectual property is still reserved by the original source and may be subject to copyright. EPISODE CAST Troian Bellisario ... Spencer Hastings Ashley Benson ... Hanna Marin Tyler Blackburn ... Caleb Rivers Lucy Hale ... Aria Montgomery Ian Harding ... Ezra Fitz Shay Mitchell ... Emily Fields Andrea Parker ... Mary Drake Janel Parrish ... Mona Vanderwaal Sasha Pieterse ... Alison Rollins Keegan Allen ... Toby Cavanaugh Huw Collins ... Dr. Elliott Rollins Lulu Brud ... Sabrina Ray Fonseca ... Bartender P a g e | 1 1 00:00:08,509 --> 00:00:10,051 How could we let this happen? 2 00:00:11,512 --> 00:00:12,972 Oh, my God, poor Hanna. 3 00:00:13,012 --> 00:00:14,807 Try to remember that it's what she'd want. 4 00:00:16,684 --> 00:00:19,561 No, I don't know if I can live with this. 5 00:00:19,603 --> 00:00:21,522 I mean, how can we bury.. 6 00:00:23,064 --> 00:00:27,027 - There has to be another way. -

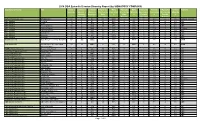

2014 DGA Episodic Director Diversity Report (By SIGNATORY COMPANY)

2014 DGA Episodic Director Diversity Report (by SIGNATORY COMPANY) Signatory Company Title Total # of Combined # Combined # Episodes Male # Episodes Male # Episodes Female # Episodes Female Network Episodes Women + Women + Directed by Caucasian Directed by Minority Directed by Caucasian Directed by Minority Minority Minority % Male % Male % Female % Female % Episodes Caucasian Minority Caucasian Minority 50/50 Productions, LLC Workaholics 13 0 0% 13 100% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0% Comedy Central ABC Studios Betrayal 12 1 8% 11 92% 0 0% 1 8% 0 0% ABC ABC Studios Castle 23 3 13% 20 87% 1 4% 2 9% 0 0% ABC ABC Studios Criminal Minds 24 8 33% 16 67% 5 21% 2 8% 1 4% CBS ABC Studios Devious Maids 13 7 54% 6 46% 2 15% 4 31% 1 8% Lifetime ABC Studios Grey's Anatomy 24 7 29% 17 71% 1 4% 2 8% 4 17% ABC ABC Studios Intelligence 12 4 33% 8 67% 4 33% 0 0% 0 0% CBS ABC Studios Mixology 12 0 0% 13 108% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0% ABC ABC Studios Revenge 22 6 27% 16 73% 0 0% 6 27% 0 0% ABC And Action LLC Tyler Perry's Love Thy Neighbor 52 52 100% 0 0% 52 100% 0 0% 0 0% OWN And Action LLC Tyler Perry's The Haves and 36 36 100% 0 0% 36 100% 0 0% 0 0% OWN The Have Nots BATB II Productions Inc. Beauty & the Beast 16 1 6% 15 94% 0 0% 1 6% 0 0% CW Black Box Productions, LLC Black Box, The 13 4 31% 9 69% 0 0% 4 31% 0 0% ABC Bling Productions Inc. -

The Community-Centered Cult Television Heroine, 1995-2007

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English English, Department of 2010 "Just a Girl": The Community-Centered Cult Television Heroine, 1995-2007 Tamy Burnett University of Nebraska at Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishdiss Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Literature in English, North America Commons, and the Visual Studies Commons Burnett, Tamy, ""Just a Girl": The Community-Centered Cult Television Heroine, 1995-2007" (2010). Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English. 27. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishdiss/27 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. “JUST A GIRL”: THE COMMUNITY-CENTERED CULT TELEVISION HEROINE, 1995-2007 by Tamy Burnett A DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Major: English (Specialization: Women‟s and Gender Studies) Under the Supervision of Professor Kwakiutl L. Dreher Lincoln, Nebraska May, 2010 “JUST A GIRL”: THE COMMUNITY-CENTERED CULT TELEVISION HEROINE, 1995-2007 Tamy Burnett, Ph.D. University of Nebraska, 2010 Adviser: Kwakiutl L. Dreher Found in the most recent group of cult heroines on television, community- centered cult heroines share two key characteristics. The first is their youth and the related coming-of-age narratives that result. -

Byron Michael Purcell and Rodney S. Diggs Intend to Continue the Legacy of the Firm in Representing the Community and Bringing Justice

Allen Crabbe Hosts Free Bas- ketball Camp at Price High School Brianna Davison Gives Back to (See page B-1) Kids with Cancer (See page D-1) VOL. LXXVV, NO. 49 • $1.00 + CA. Sales Tax THURSDAY, DECEMBER 12 - 18, 2013 VOL. LXXXV NO. 33, $1.00 +CA. Sales Tax“For Over “For Eighty Over Eighty Years Years, The Voice The Voiceof Our of CommunityOur Community Speaking Speaking for forItself Itself.” THURSDAY, AUGUST 15, 2019 Byron Michael Purcell and Rodney S. Diggs intend to continue the legacy of the firm in representing the community and bringing justice. BY BRIAN W. CARTER Contributing Writer Welcome Ivie, Mc- Neill, Wyatt, Purcell & Diggs—the prestigious and Black-owned law firm in Los Angeles has added two exemplary lawyers to its title. IMW partners, Byron Michael Purcell and Rodney S. Diggs both come with a wealth of le- gal experience between the two of them and prov- en records at the firm. Se- nior partners, Rickey Ivie and Keith Wyatt shared a statement about adding their names to the firm. “Byron and Rodney have been major contribu- (From left) IMW attorneys Byron Michael Purcell and tors to the success and Rodney S Diggs. COURTESY growth of our firm for a (From left) Motown legends Smokey Robinson and Berry Gordy PHOTO E. MESIYAH MCGINNIS / SENTINEL long time. The change of dous attorneys, and we are is committed to service, the firm name is in recog- proud and blessed to work I love the commitment to BY IMANI SUMBI Harmony Gold Theater in ford, and of course, mem- nition of their past, pres- with them.”- Rickey Ivie & service—not only to its cli- Contributing Writer Los Angeles. -

Detectives with Pimples: How Teen Noir Is Crossing the Frontiers of the Traditional Noir Films1

Detectives with pimples: How teen noir is crossing the frontiers of the traditional noir films1 João de Mancelos (Universidade da Beira Interior) Palavras-chave: Teen noir, Veronica Mars, cinema noir, reinvenção, feminismo Keywords: Teen noir, Veronica Mars, noir cinema, reinvention, feminism 1. “If you’re like me, you just keep chasing the storm” In the last ten years, films and TV series such as Heathers (1999), Donnie Darko (2001), Brick (2005) or Veronica Mars (2004-2007) have become increasingly popular and captivated cult audiences, both in the United States and in Europe, while arousing the curiosity of critics. These productions present characters, plots, motives and a visual aesthetic that resemble the noir films created between 1941, when The Maltese Falcon premiered, and 1958, when Touch of Evil was released. The new films and series retain, for instances, characters like the femme fatale, who drags men to a dreadful destiny; the good-bad girl, who does not hesitate in resorting to dubious methods in order to achieve morally correct objectives; and the lonely detective, now a troubled adolescent — as if Sam Spade had gone back to High School. In the first decade of our century, critics coined the expression teen noir to define this new genre or, in my opinion, subgenre, since it retains numerous traits of the classic film noir, especially in its contents, thus not creating a significant rupture. In this article, I intend to a) examine the common elements between teen noir series and classic noir films; b) analyze how this new production reinvents or subverts the characteristics of the old genre, generating a sense of novelty; c) detect some of the numerous intertextual references present in Veronica Mars, which may lead young viewers to investigate other series, movies or books. -

Completeandleft

MEN WOMEN 1. BA Bryan Adams=Canadian rock singer- Brenda Asnicar=actress, singer, model=423,028=7 songwriter=153,646=15 Bea Arthur=actress, singer, comedian=21,158=184 Ben Adams=English singer, songwriter and record Brett Anderson=English, Singer=12,648=252 producer=16,628=165 Beverly Aadland=Actress=26,900=156 Burgess Abernethy=Australian, Actor=14,765=183 Beverly Adams=Actress, author=10,564=288 Ben Affleck=American Actor=166,331=13 Brooke Adams=Actress=48,747=96 Bill Anderson=Scottish sportsman=23,681=118 Birce Akalay=Turkish, Actress=11,088=273 Brian Austin+Green=Actor=92,942=27 Bea Alonzo=Filipino, Actress=40,943=114 COMPLETEandLEFT Barbara Alyn+Woods=American actress=9,984=297 BA,Beatrice Arthur Barbara Anderson=American, Actress=12,184=256 BA,Ben Affleck Brittany Andrews=American pornographic BA,Benedict Arnold actress=19,914=190 BA,Benny Andersson Black Angelica=Romanian, Pornstar=26,304=161 BA,Bibi Andersson Bia Anthony=Brazilian=29,126=150 BA,Billie Joe Armstrong Bess Armstrong=American, Actress=10,818=284 BA,Brooks Atkinson Breanne Ashley=American, Model=10,862=282 BA,Bryan Adams Brittany Ashton+Holmes=American actress=71,996=63 BA,Bud Abbott ………. BA,Buzz Aldrin Boyce Avenue Blaqk Audio Brother Ali Bud ,Abbott ,Actor ,Half of Abbott and Costello Bob ,Abernethy ,Journalist ,Former NBC News correspondent Bella ,Abzug ,Politician ,Feminist and former Congresswoman Bruce ,Ackerman ,Scholar ,We the People Babe ,Adams ,Baseball ,Pitcher, Pittsburgh Pirates Brock ,Adams ,Politician ,US Senator from Washington, 1987-93 Brooke ,Adams -

SAFER at HOME in Select Theaters, VOD & Digital on February 26, 2021

SAFER AT HOME In Select Theaters, VOD & Digital on February 26, 2021 DIRECTED BY Will Wernick WRITTEN BY Will Wernick, Lia Bozonelis PRODUCED BY Will Wernick, John Ierardi, Bo Youngblood, Lia Bozonelis (Co-Producer), Jason Phillips (Co-Producer) STARRING Jocelyn Hudon, Emma Lahana, Alisa Allapach, Adwin Brown, Dan J. Johnson, Michael Kupisk, Daniel Robaire RUN TIME: 82 mins DISTRIBUTED BY: Vertical Entertainment For additional information please contact: LA Daniel Coffey – [email protected] Emily Maroon – [email protected] NY Susan Engel – [email protected] Danielle Borelli – [email protected] ABOUT THE FILM Synopsis Two years into the pandemic, a group of friends throw an online party with a night of games, drinking and drugs. After taking an ecstasy pill, things go terribly wrong and the safety of their home becomes more terrifying than the raging chaos outside. Director’s Statement Making Safer at Home was challenging. Not just because of the technical hurdles the pandemic mandated, but because of the strange new features life had taken on in those early months of the pandemic. I found myself having unusual conversations, and realizations about myself and friends — things that only this type of stress could bring out. I noticed people making major, sometimes life changing decisions, quickly. Brake-ups, pregnancies, divorces, fights-- this instigated them all. Almost everyone I knew was caught in an indefinite cycle of every day feeling the same. And then we started working on this film. Safer at Home plays out essentially in real time, and shows what a long period of lockdown could do to a group of friends. -

Wanted: Dead Or Alive”

CREATED BY I. Marlene King BASED ON THE BOOKS BY Sara Shepard EPISODE 7.06 “Wanted: Dead or Alive” Hanna struggles with whether to tell the police the truth about Rollins. Emily challenges Jenna, who reveals part of her plot. WRITTEN BY: Lijah Barasz DIRECTED BY: Bethany Rooney ORIGINAL BROADCAST: August 2, 2016 NOTE: This is a transcription of the spoken dialogue and audio, with time-code reference, provided without cost by 8FLiX.com for your entertainment, convenience, and study. This version may not be exactly as written in the original script; however, the intellectual property is still reserved by the original source and may be subject to copyright. EPISODE CAST Troian Bellisario ... Spencer Hastings Ashley Benson ... Hanna Marin Tyler Blackburn ... Caleb Rivers Lucy Hale ... Aria Montgomery Ian Harding ... Ezra Fitz Shay Mitchell ... Emily Fields Andrea Parker ... Mary Drake Janel Parrish ... Mona Vanderwaal (credit only) Sasha Pieterse ... Alison Rollins Vanessa Ray ... CeCe Drake / Charlotte DiLaurentis Huw Collins ... Dr. Elliott Rollins / Archer Dunhill Dre Davis ... Sara Harvey Nicholas Gonzalez ... Detective Marco Furey Tammin Sursok ... Jenna Marshall Dawn Brodey ... Maid P a g e | 1 1 00:00:07,925 --> 00:00:10,051 Aria, I called you last night 2 00:00:10,093 --> 00:00:12,220 after you went to Ezra's. 3 00:00:12,262 --> 00:00:15,015 Yeah. I'm sorry I didn't get back to you. 4 00:00:15,056 --> 00:00:16,183 Well, is everything okay? 5 00:00:16,224 --> 00:00:18,059 Did he find out about the Nicole call? 6 00:00:18,101 --> 00:00:19,979 No, he didn't.