Textile & IP Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Diplomski Rad Tekstilni Uzorci I Ornamenti Svjetskih Kultura U Suvremenoj Primjeni Na Kupaćim Kostimima

SVEUČILIŠTE U ZAGREBU TEKSTILNO-TEHNOLOŠKI FAKULTET DIZAJN TEKSTILA DIPLOMSKI RAD TEKSTILNI UZORCI I ORNAMENTI SVJETSKIH KULTURA U SUVREMENOJ PRIMJENI NA KUPAĆIM KOSTIMIMA Antonija Bunčuga Zagreb, rujan 2019. SVEUČILIŠTE U ZAGREBU TEKSTILNO-TEHNOLOŠKI FAKULTET DIZAJN TEKSTILA DIPLOMSKI RAD TEKSTILNI UZORCI I ORNAMENTI SVJETSKIH KULTURA U SUVREMENOJ PRIMJENI NA KUPAĆIM KOSTIMIMA Mentor: Student : Izv.prof.art. Koraljka Kovač Dugandžić AntonijaBunčuga, 11019/TMD –DT. Zagreb, rujan 2019. UNIVERSITY OF ZAGREB FACULTY OF TEXTILE TECHNOLOGY DEPARTMENT OF TEXTILE AND FASHION DESIGN GRADUATE THESIS TEXTILE PATTERNS AND ORNAMENTS OF WORLD CULTURES IN MODERN APPLICATION ON SWIMSUIT Mentor: Student : Izv. prof. art. Koraljka Kovač Dugandžić AntonijaBunčuga, 11019/TMD –DT. Zagreb, September 2019. DOKUMENTACIJSKA KARTICA • Zavod za dizajn tekstila i odjeće, Zavod za projektiranje i menadžment tekstila • Broj stranica: 50 • Broj slika: 46 • Broj literaturnih izvora: 19 • Broj likovnih ostvarenja: tekstilnih uzoraka + vizualizacije: 10 • Članovi povjerenstva za ocjenu i obranu diplomskog rada: 1. Izv. prof. dr. sc. Martinia Ira Glover 2. Izv. prof. art. Koraljka Kovač Dugandžić 3. Red. prof. art. Andera Pavetić 4. Prof. dr. sc. Irena Šabarić (zamjenica) 1 SAŽETAK Diplomski rad pod nazivom „Tekstilni uzorci i ornamenti svjetskih kultura u suvremenoj primjeni na kupaćim kostimima“ prikazuje detaljni pregled odabranih triju kontinenata: Meksika, Afrike i Indije. Opisuje ornamente, uzorke, tehnike i motive s tradicionalne odjeće odabranih područja uz primjere fotografija. Nakon teorijske obrade dat je pregled tekstilnih uzoraka, koji su nastali prema inspiraciji, na ornamente i uzorke odabranih svjetskih kultura. Tekstilni uzorci su prikazani kroz kolekciju od pet modela kupaćih kostima. Na samom kraju predstavljena je njegova namjena i plasiranje na tržište. Ključne riječi: ornament, uzorak, kultura, kupaći kostim, tekstil. -

Probe on Royal Deaths

VOL.I WEDNESDAY K 24 K Y Y M ISSUE NO.253 M C AUGUST, 2016 C BHUBANESWAR THE KALINGA CHRONICLE PAGES-8 2.50 (Air Surcharge - 0.50P) FIND US ON FOLLOW US facebook.com/thekalingachronicle Popular People’s Daily of Odisha ON TWITTER twitter.com/ thekalingachronicle Probe on Royal Deaths China eyes Odisha Bhubaneswar (KC- It is expected Chinese repre- Bhubaneswar (KC- The Police on "house arrest" and August found out priating royal prop- N): As China experi- that collaborations sentatives said they N): A day after the 21 August recovered "misappropriation of Sanjay Patra's body erty". ence over produc- between India and are encouraged by mysterious deaths of bodies of the former royal family proper- hanging from the In a letter to the tion in all sectors, China will carry for- the new IPR Policy former manager of palace Manager ties". ceiling while bodies Chief Minister, Parlakhemundi pal- Anang Manjari Patra, Meanwhile, of Anang Manjari and Mr.Deb's daughter ace Anang Manjari her brother and Ma- three suicide notes her sister Bijaylaxmi Kalyani Devi, who is Patra and her two sib- haraja Gopinath have been recovered were found in an- currently staying in from Anang Manjari other room of the Chennai, had urged Patra's house, DGP House. him to inquire into K B Singh told Me- Santosh alias the property transac- dia Men here.He said Tulu was rescued in tions of the royal the suicide notes critical condition family for the past were written in sepa- from the kitchen, 35 years. rate handwritings. -

Unfinished Business

CHRISTMAS RUSH DELIVERY PRE-FALL WISH 2015 DESIGNERS AND LOOKS FROM CELEBRITIES REVEAL WHAT WON HUNDRED, THEY HOPE TO FIND UNDER NOON BY NOOR THEIR TREES ON THURSDAY. AND PINK RETAILERS STEP UP THEIR DRIVE TO DELIVER TARTAN. PAGE 6 PAGES 10 AND 11 SHOPPERS’ LAST-MINUTE HOLIDAY ORDERS. PAGE 9 WWDTUESDAY, DECEMBER 23, 2014 ■ $3.00 ■ WOMEN’S WEAR DAILY HOLIDAY’S FINAL COUNTDOWN Saturday Seemed Super, But Season Might Not Be There also was a strong feeling By DAVID MOIN that consumers still are holding and SHARON EDELSON back their purchasing, playing the same waiting game with retailers SUPER SATURDAY proved to be that they’ve done in recent years. the biggest shopping day of the year “Over the past few years, we’ve no- yet did little to change the modest ticed a trend in customers waiting outlook for the holiday season. until the last minute to fi nish their While last weekend marked the shopping,” said Scott McCall, senior second decent one in a row after vice president of merchandising for early December’s deep lull, the Wal-Mart U.S. “While many custom- forecast for holiday 2014 stands at ers start their Christmas shopping low-single-digit gains for retailing in November, the majority don’t put generally, with the apparel sector their lists away until Dec. 24.” falling far short of that. “There was only about a 2 per- “There are no trends to make cent increase on Super Saturday people feel they have to buy ap- weekend, with $42 billion in sales parel,” said Claudio Del Vecchio, versus last year’s $41 billion,” chairman and chief executive of- said Craig Johnson, president fi cer of Brooks Brothers. -

Indian-Luxury-Top-50-Women Final

O Most Powerful Women of 2020 Prologue espite the global instability and slump “People are in the Indian economy, the Indian luxury industry is fighting hard to survive looking for and make profits. Over the past few authentic months, Indian luxury leaders have D observed that a consumer’s idea of luxury has experiences evolved. He/she is opting for holistic experiences – whether it’s and just a brand name is not lure-worthy any longer. Take, for example, the F&B industry—people vacations, travel want to know if the ingredients are indigenous, or products” if the food items are organic or gluten-free and what are the safety measures implemented by the restaurant. The meaning of luxury has changed and the They want to indulge, but are looking for guilt-free new-age customers are looking for something that indulgence. Companies are coming up with newer is truly unique and personalised, be it a traditional and unique services and products to offer. Take, for Pichwai painting or a piece of handcrafted jewellery or example, Deepika Gehani, who collaborated with an organic Ayurvedic skincare product. Satya Paul to give the good old sari a new avatar or To celebrate the growth of this niche industry, Khushi Singh, who has redefined luxury weddings. we at LuxeBook, have curated a list of 50 feisty and R ajshree Pathy has noted that people are looking confident women thought leaders, who have stood for authentic experiences – whether it’s vacations, out in the ever-changing luxe market. travel or products. Millennials, the new luxury Let’s raise a toast to these fabulous ladies! consumers, are looking for elegance in products and services; which comes from the highest level of craftsmanship and extensively researched materials, says designer Ritu Kumar. -

FD Er\Vd `Fe S`^Svc YVRUVU W`C Rzca`Ce

- . < * " 8 " 8 8 +,$#+-).*/ /$4!4/! 3/0)# $/012 * 0 );* 7O:((:) 9::9: 4;1;61)C ;7$5764):9 3$:* 73$63 );9 1 315 5);)=&@; 1 1 )$51 5*61 $ )5 1$ (5)5(6(*1:1 ((; (575 1@ (* 5)5) 0 367;1:(5D$; ;$1 6) $@;1 3 A5B @9 7 &'()* ++! => ? ; 0 011)2 )11 ! P "! "L$ & & M " ( ) * +)*, % );9;7$5 - ./ 4 36789 $5):) he national unemployment *01 Trate rose to 8. 1 per cent in / he US military confirmed the week ended August 28 as 2 Ton Sunday that it targeted against 6.95 per cent in July. " an “explosive laden vehicle” This is despite the fact that headed towards Kabul’s inter- most of the States and Union national airport where the territories have fully reopened American military is involved their economy after a decline in !"#$ ) in an evacuation operation. the ferocity of the second 3+)3, “US military forces Covid-19 wave. 4 conducted a self-defence Rural unemployment took 8.38 per cent and 9.71 per cent unemployment in urban India unmanned over-the-horizon a sharp upward turn to 7.3 per while rural unemployment has stayed below 9 per cent, 2 air strike today on a vehicle in cent from 6.34 per cent and remained between 6.53 per and at the national level, it has ( Kabul, eliminating an immi- American military’s evacua- urban joblessness rose to 9.7 cent and 7.31 per cent during remained under 8 per cent. The nent ISIS-K threat to Hamid tion there. -

Fashion Text Book

Fashion STUDIES Text Book CLASS-XII CENTRAL BOARD OF SECONDARY EDUCATION Preet Vihar, Delhi - 110301 FashionStudies Textbook CLASS XII CENTRAL BOARD OF SECONDARY EDUCATION Shiksha Kendra, 2, Community Centre, Preet Vihar, Delhi-110 301 India Text Book on Fashion Studies Class–XII Price: ` First Edition 2014, CBSE, India Copies: "This book or part thereof may not be reproduced by any person or agency in any manner." Published By : The Secretary, Central Board of Secondary Education, Shiksha Kendra, 2, Community Centre, Preet Vihar, Delhi-110301 Design, Layout : Multi Graphics, 8A/101, W.E.A. Karol Bagh, New Delhi-110005 Phone: 011-25783846 Printed By : Hkkjr dk lafo/ku mísf'kdk ge] Hkkjr ds yksx] Hkkjr dks ,d lEiw.kZ 1¹izHkqRo&laiUu lektoknh iaFkfujis{k yksdra=kkRed x.kjkT;º cukus ds fy,] rFkk mlds leLr ukxfjdksa dks% lkekftd] vkfFkZd vkSj jktuSfrd U;k;] fopkj] vfHkO;fDr] fo'okl] /eZ vkSj mikluk dh Lora=krk] izfr"Bk vkSj volj dh lerk izkIr djkus ds fy, rFkk mu lc esa O;fDr dh xfjek vkSj 2¹jk"Vª dh ,drk vkSj v[kaMrkº lqfuf'pr djus okyh ca/qrk c<+kus ds fy, n`<+ladYi gksdj viuh bl lafo/ku lHkk esa vkt rkjh[k 26 uoEcj] 1949 bZñ dks ,rn~ }kjk bl lafo/ku dks vaxhÑr] vf/fu;fer vkSj vkRekfiZr djrs gSaA 1- lafo/ku (c;kyhloka la'kks/u) vf/fu;e] 1976 dh /kjk 2 }kjk (3-1-1977) ls ¶izHkqRo&laiUu yksdra=kkRed x.kjkT;¸ ds LFkku ij izfrLFkkfirA 2- lafo/ku (c;kyhloka la'kks/u) vf/fu;e] 1976 dh /kjk 2 }kjk (3-1-1977) ls ¶jk"Vª dh ,drk¸ ds LFkku ij izfrLFkkfirA Hkkx 4 d ewy dÙkZO; 51 d- ewy dÙkZO; & Hkkjr ds izR;sd ukxfjd dk ;g dÙkZO; gksxk fd og & (d) lafo/ku -

September, 2020

MANTHAN Current Affairs Supplement – September, 2020 wzz MANTHAN September, 2020 Page : 1 MANTHAN Current Affairs Supplement – September, 2020 Preface Dear Readers, The “Current Affairs” section is an integral part of any examination. This edition of Manthan has been developed by our team to help you cover all the important events of the month for the upcoming exams like Banking, Insurance, CLAT, MBA etc. This comprehensive bulletin will help you prepare the section in a vivid manner. We hope that our sincere efforts will serve you in a better way to fulfil aspirations. Happy Reading! Best Wishes Team CL MANTHAN September, 2020 Page : 2 MANTHAN Current Affairs Supplement – September, 2020 CONTENTS POLITY AND GOVERNANCE .................................................................................................................................. 4 National......................................................................................................................................................................... 4 International..................................................................................................................................................................30 ECONOMY AND FINANCE ................................................................................................................................... 40 Economy News ............................................................................................................................................................40 Banks in News -

Page 01 DT March 24.Indd

[email protected] TUESDAY 24 MARCH 2015 • www.thepeninsulaqatar.com • 4455 7741 LULU-AL MANA & PARTNERS PROMOTION KEY HANDING OVER CEREMONY P | 5 In 20 years, almost 3,300 students have graduated from the different schools and universities at Qatar Foundation. This includes 844 graduates from the eight pre-university academic institutes housed by QF, five Qatar Academy schools, Qatar Leadership Academy, Awsaj Academy, and the Academic Bridge Program. NO STYLE GREATER THAN COMFORT, SAYS KAREENA KAPOOR KHAN P | 8 BIOGEN’S ALZHEIMER’S DRUG SLOWS MENTAL DECLINE IN EARLY STUDY P | 11 P | 2-3 | TUESDAY 24 MARCH 2015 | 02 EDUCATION n 20 years, almost 3,300 students have graduated from the different Qatar Foundation: Preparing schools and universities at Qatar IFoundation (QF). This includes 844 graduates from the eight pre-university academic institutes housed a generation of leaders by QF, five Qatar Academy schools, Qatar Leadership Academy, Awsaj Academy, and the Academic Bridge Program. Additionally, more than 2,500 students have graduated from the universities at Education City, including Hamad Bin Khalifa University (HBKU) and its partner universities. Many of these students are now working across a variety of public and private sector fields, including oil & gas, engineering, tech- nology, communications, construction, and finance as well as education and science. For the last two decades, QF has worked diligently to establish a unique educational environment that offers well-developed, comprehensive academic programmes to prepare the next generation of Qataris. By helping to develop well-educated and highly-skilled graduates. The story of QF started when H H Sheikha Moza bint Nasser, Chairperson of Qatar Foundation, recognised the need to provide quality education to the youth while preserving the local culture and traditions. -

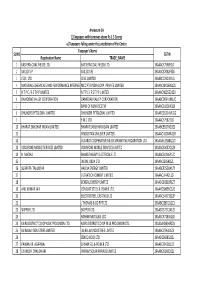

FINAL DISTRIBUTION.Xlsx

Annexure-1A 1)Taxpayers with turnover above Rs 1.5 Crores a) Taxpayers falling under the jurisdiction of the Centre Taxpayer's Name SL NO GSTIN Registration Name TRADE_NAME 1 EASTERN COAL FIELDS LTD. EASTERN COAL FIELDS LTD. 19AAACE7590E1ZI 2 SAIL (D.S.P) SAIL (D.S.P) 19AAACS7062F6Z6 3 CESC LTD. CESC LIMITED 19AABCC2903N1ZL 4 MATERIALS CHEMICALS AND PERFORMANCE INTERMEDIARIESMCC PTA PRIVATE INDIA CORP.LIMITED PRIVATE LIMITED 19AAACM9169K1ZU 5 N T P C / F S T P P LIMITED N T P C / F S T P P LIMITED 19AAACN0255D1ZV 6 DAMODAR VALLEY CORPORATION DAMODAR VALLEY CORPORATION 19AABCD0541M1ZO 7 BANK OF NOVA SCOTIA 19AAACB1536H1ZX 8 DHUNSERI PETGLOBAL LIMITED DHUNSERI PETGLOBAL LIMITED 19AAFCD5214M1ZG 9 E M C LTD 19AAACE7582J1Z7 10 BHARAT SANCHAR NIGAM LIMITED BHARAT SANCHAR NIGAM LIMITED 19AABCB5576G3ZG 11 HINDUSTAN UNILEVER LIMITED 19AAACH1004N1ZR 12 GUJARAT COOPERATIVE MILKS MARKETING FEDARATION LTD 19AAAAG5588Q1ZT 13 VODAFONE MOBILE SERVICES LIMITED VODAFONE MOBILE SERVICES LIMITED 19AAACS4457Q1ZN 14 N MADHU BHARAT HEAVY ELECTRICALS LTD 19AAACB4146P1ZC 15 JINDAL INDIA LTD 19AAACJ2054J1ZL 16 SUBRATA TALUKDAR HALDIA ENERGY LIMITED 19AABCR2530A1ZY 17 ULTRATECH CEMENT LIMITED 19AAACL6442L1Z7 18 BENGAL ENERGY LIMITED 19AADCB1581F1ZT 19 ANIL KUMAR JAIN CONCAST STEEL & POWER LTD.. 19AAHCS8656C1Z0 20 ELECTROSTEEL CASTINGS LTD 19AAACE4975B1ZP 21 J THOMAS & CO PVT LTD 19AABCJ2851Q1Z1 22 SKIPPER LTD. SKIPPER LTD. 19AADCS7272A1ZE 23 RASHMI METALIKS LTD 19AACCR7183E1Z6 24 KAIRA DISTRICT CO-OP MILK PRO.UNION LTD. KAIRA DISTRICT CO-OP MILK PRO.UNION LTD. 19AAAAK8694F2Z6 25 JAI BALAJI INDUSTRIES LIMITED JAI BALAJI INDUSTRIES LIMITED 19AAACJ7961J1Z3 26 SENCO GOLD LTD. 19AADCS6985J1ZL 27 PAWAN KR. AGARWAL SHYAM SEL & POWER LTD. 19AAECS9421J1ZZ 28 GYANESH CHAUDHARY VIKRAM SOLAR PRIVATE LIMITED 19AABCI5168D1ZL 29 KARUNA MANAGEMENT SERVICES LIMITED 19AABCK1666L1Z7 30 SHIVANANDAN TOSHNIWAL AMBUJA CEMENTS LIMITED 19AAACG0569P1Z4 31 SHALIMAR HATCHERIES LIMITED SHALIMAR HATCHERIES LTD 19AADCS6537J1ZX 32 FIDDLE IRON & STEEL PVT. -

India Celebrates 70Th Republic

We Wish Readers a Happy Republic Day of India EVER TRUTHFUL # 1 Indian American Weekly: Since 2006 VOL 13 ISSUE 04 ● NEW YORK / DALLAS ● JANUARY 25 - 31, 2019 ● ENQUIRIES: 646-247-9458 www.theindianpanorama.news 15th Edition of Pravasi Bharatiya India celebrates 70th Republic Day Divas Concludes page 3 ● South African President Cyril Ramaphosa attends as Chief Guest ● Impressive Parade and enthusiasm mark the celebration Federal Government Shutdown ● Ends after a 35 -day Stand off PM lays a wreath at Amar Jawan Jyoti and pays tribute to martyrs NEW DELHI (TIP): Celebrations for the Trump Signs Bill Reopening Government 70th Republic Day began on Saturday, January for 3 Weeks through February 15 26, with South African President Cyril Ramaphosa in attendance as the chief guest, President Trump amid heavy security deployment in the city. announcing that "we have reached a deal Prime Minister Narendra Modi paid his to end the tributes to the martyrs by laying a wreath at shutdown." He has Amar Jawan Jyoti in the presence of Defense since signed a bill Minister Nirmala Sitharaman and the three which will keep service chiefs. Later Modi, wearing his government open traditional kurta-pajama and trademark through February 15 Nehru jacket, reached the Rajpath and received and greeted President Ram Nath Kovind and WASHINGTON (TIP): The House and Senate both the chief guest. contd on Page 38 approved a measure Friday, January 25 to temporarily reopen the federal government with a short-term Prime Minister Modi greets Chief Guest South spending bill that does not include President Donald African President Cyril Ramaphosa at Rajpath contd on Page 38 Photo / courtesy PIB Dr. -

Arshad Farooq, Muhammad Atiq and Commodore Irfan Taj Seen During the Book Launch Event

Community Community ICC organises Finnish- event Pakistani P6featuring a P16 writer performance by launches book in Bharatanatyam Qatar at an event dancer Veena C organised by Seshadri. APOO World. Sunday, April 7, 2019 Sha’baan 2, 1440 AH Doha today: 230 - 330 Photo by Sajith Orma Sassy Sonam OVER Sassy Sonam C STORY Exclusive interview with the Bollywood star who was in town recently to judge Fashion Trust Arabia. P4-5 LIFESTYLE SHOWBIZ Positive workplace raises What post-credits scene of productivity in employees. Shazam! means. Page 14 Page 15 2 GULF TIMES Sunday, April 7, 2019 COMMUNITY ROUND & ABOUT PRAYER TIME Fajr 4.00am Shorooq (sunrise) 5.20am Zuhr (noon) 11.36am Asr (afternoon) 3.05pm Maghreb (sunset) 5.53pm Isha (night) 7.23pm Shazam! Shazam revels in the new version of himself by doing what any USEFUL NUMBERS DIRECTION:David F Sandberg other teen would do – have fun while testing out his newfound CAST: Zachary Levi, Michelle Borth, Djimon Hounsou powers. But he’ll need to master them quickly before the evil SYNOPSIS: We all have a superhero inside of us – it Dr. Thaddeus Sivana can get his hands on Shazam’s magical just takes a bit of magic to bring it out. In 14-year-old Billy abilities. Batson’s case, all he needs to do is shout out one word to transform into the adult superhero Shazam. Still a kid at heart, THEATRES: The Mall, Royal Plaza, Landmark Emergency 999 Worldwide Emergency Number 112 Kahramaa – Electricity and Water 991 Local Directory 180 International Calls Enquires 150 Hamad International Airport 40106666 Labor -

JK a 'Jewel' of Country, Industrial Package For

K K M Sports: Bajrang, Ravi Kumar claim National: Nirbhaya convicts hanging: Tihar Local: Sat dedicates newly constructed lane International: Trump trial could be over M Y Y C gold medals in Rome Ranking .... P9 jail seeks services of UP executioner............ P7 to inhabitants of Patta Chungi...................... P3 in two weeks......................................................... P8 C JAMMU, MONDAY, JANUARY 20, 2020 VOL. 35 | NGO.20 | REGD. NlO. : JMi/JK 118m/15 /17 | E-mail : [email protected] |wwew.glimpsesosffuture.com | Prioce : Rs. 2.00 f Futuepaprer.glimepsesoffuture.com Union ministers'' J&K JK a 'jewel' of country, Industrial visit continues on day 2 GOF STAFF REPORTER These apart, Union minis Jammu, Jan 19 ter Jitendra Singh visited Udhampur, R.K. Dodha package for UT soon: Goyal Continuing with its and Ashwini Choubey visit public outreach program ed Samba. This was the sec across Jammu andond day of a weeklong tour Kashmir, nine Union min of 36 Union ministers who Kashmir would be linked with the rest of the country by train by December next year isters visited nine places ar are to visit 60 locations GOF STAFF REPORTER rest of the country by train by of investment coming to dressed a series of public meet earth and it will remain so as well. eas across Jammu region across Jammu and Kashmir Jammu, Jan 19 December next year. He asserted Kashmir," he told reporters at the ings and inaugurated various It is a jewel of the country and tru on Sunday. as the part of Centre''s pub Union minister Smriti that development work has gath Jammu airport before returning projects in different districts.