Explosive Weapons Use in Syria, Report 4 Northeast Syria: Al Hassakeh, Ar Raqqa, and Deir Ez Zor Governorates

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Policy Notes for the Trump Notes Administration the Washington Institute for Near East Policy ■ 2018 ■ Pn55

TRANSITION 2017 POLICYPOLICY NOTES FOR THE TRUMP NOTES ADMINISTRATION THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY ■ 2018 ■ PN55 TUNISIAN FOREIGN FIGHTERS IN IRAQ AND SYRIA AARON Y. ZELIN Tunisia should really open its embassy in Raqqa, not Damascus. That’s where its people are. —ABU KHALED, AN ISLAMIC STATE SPY1 THE PAST FEW YEARS have seen rising interest in foreign fighting as a general phenomenon and in fighters joining jihadist groups in particular. Tunisians figure disproportionately among the foreign jihadist cohort, yet their ubiquity is somewhat confounding. Why Tunisians? This study aims to bring clarity to this question by examining Tunisia’s foreign fighter networks mobilized to Syria and Iraq since 2011, when insurgencies shook those two countries amid the broader Arab Spring uprisings. ©2018 THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY ■ NO. 30 ■ JANUARY 2017 AARON Y. ZELIN Along with seeking to determine what motivated Evolution of Tunisian Participation these individuals, it endeavors to reconcile estimated in the Iraq Jihad numbers of Tunisians who actually traveled, who were killed in theater, and who returned home. The find- Although the involvement of Tunisians in foreign jihad ings are based on a wide range of sources in multiple campaigns predates the 2003 Iraq war, that conflict languages as well as data sets created by the author inspired a new generation of recruits whose effects since 2011. Another way of framing the discussion will lasted into the aftermath of the Tunisian revolution. center on Tunisians who participated in the jihad fol- These individuals fought in groups such as Abu Musab lowing the 2003 U.S. -

Deir Ez-Zor: Dozens Arbitrarily Arrested During SDF's “Deterrence

Deir ez-Zor: Dozens Arbitrarily Arrested during SDF’s “Deterrence of Terrorism” Campaign www.stj-sy.org Deir ez-Zor: Dozens Arbitrarily Arrested during SDF’s “Deterrence of Terrorism” Campaign This joint report is brought by Justice For Life (JFL) and Syrians for Truth and Justice (STJ) Page | 2 Deir ez-Zor: Dozens Arbitrarily Arrested during SDF’s “Deterrence of Terrorism” Campaign www.stj-sy.org 1. Executive Summary The Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) embarked on numerous raids and arrested dozens of people in its control areas in Deir ez-Zor province, located east of the Euphrates River, during the “Deterrence of Terrorism” campaign it first launched on 4 June 2020 against the cells of the Islamic State (IS), aka Daesh. The reported raids and arrests were spearheaded by the security services of the Autonomous Administration and the SDF, particularly by the Anti-Terror Forces, known as the HAT.1 Some of these raids were covered by helicopters of the US-led coalition, eyewitnesses claimed. In the wake of the campaign’s first stage, the SDF announced that it arrested and detained 110 persons on the charge of belonging to IS, in a statement made on 10 June 2020,2 adding that it also swept large-scale areas in the suburbs of Deir ez-Zor and al-Hasakah provinces. It also arrested and detained other 31 persons during the campaign’s second stage, according to the corresponding statement made on 21 July 2020 that reported the outcomes of the 4- day operation in rural Deir ez-Zor.3 “At the end of the [campaign’s] second stage, the participant forces managed to achieve the planned goals,” the SDF said, pointing out that it arrested 31 terrorists and suspects, one of whom it described as a high-ranking IS commander. -

Bombing! Incidents by Target 1978-1987 10-YEAR TARGET % YEARLY GRAND TOTALIRANI{ 1978 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 I 1986 1987 TOTAL TOTAL Residential

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. ..• I .....-. • - ... --. 8 i i II' .- , ,. ... • .,1 ,. '. ~ I .,...-.., .. ·.i~1~~ D ... IIJ • I • -e '"• "';:.~ 111 .. -- - ;.,;; '(', ' .. ~. '1'. .. ~ ;~'E·~"~';""">·'\.':;··"'~:""',*"f~·'1~.";' ~'I:{~~~ 121008 U.S. Department of Justice National Institute of Justice This document has been reproduced exactly as received from ·the person or organization originating it. Points of view or opinions stated in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official pOl'ition or policies of the National Institute of Justice. Permission to reproduce this c~g~qmaterial has been granted by ". Public Domain/Bur. of Alcohol, Tobacco & Firearms/US Dept. of llh~ffam,};1fc¥iminal Justice Reference Service (NCJRS). Further rep=~utslde of the NCJRS system requires permis- sion of the . wner. Cover: On January 12, 1987, an explosive device detonated between the front and rear seats of a Beechcraft aircraft while it was parked at the Osceola Municipal Allport, Osceola,'Arkansas. A TF assistance was requested by the Osceola Police Department. ATF responded to the scene and conducted a crime scene search. A joint investigation by ATF, the Arkansas State Police, and the Osceola Police Department ensued. A preliminary investigation revealed that a destructive device consisting of suspected dynamite had been placed inside the aircraft. The explosion caused damages estimated at $10,000 but no injuries. On February 12, 1987, a second explosive device.detonated inside the passenger compartment of another private aircraft at the Osceola airport. There were no deaths or ~uries, but damages were estimated at $15,000. -

Deir-Ez-Zor Governorate - Gender-Based Violence Snapshot, January - June 2016

Deir-ez-Zor Governorate - Gender-Based Violence Snapshot, January - June 2016 Total Population: 0.94 mio No. of Sub-Districts: 14 Total Female Population: 0.46 mio No. of Communities: 133 Total Population > Age of 18: 0.41 mio No. of Hard-to-Reach Locations: 133 IDPs: 0.32 mio No. of Besieged Locations: 0 People in Need: 0.75 mio GOVERNORATE HIGHLIGHTS & CAPACITY BUILDING INITIATIVES: Ar-Raqqa P ! • Several GBV training sessions were provided in Basira, Kisreh and Sur ! sub-districts Kisreh Tabni Sur Deir-ez-Zor P Deir-ez-Zor Khasham Basira NUMBER OF ORGANIZATIONS BY ACTIVITY IN EACH SUB-DISTRICT Awareness Raising Dignity Kits Distribution Psychosocial Support IRAQIRAQ Skills Building & Livelihoods Specialised Response Muhasan Thiban P Governorate Capitals Governorate Boundaries Al Mayadin District Boundaries Sub-District Boundaries Hajin Ashara GBV Reach !1 -!>5 Women and Girls Safe Spaces (Jun 2016) 1 1 1 !1 - >5 Women and Girls Safe Spaces (Jan-May 2016) Jalaa ! Areas of Influence (AoI) Syria Susat Contested Areas Golan Heights Abu Kamal Government (SAA) ´ ISIS-affiliated groups A S H A R A D E I R - E Z - Z O R M U H A S A N Kurdish Forces NUMBER OF ORGANIZATIONS BY HUB IN EACH SUB -DISTRICT Non-state armed groups and ANF Amman Hub Damascus Hub Gaziantep Hub Unspecified Disclaimer: The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsment. This map is based on available data 0 12.5 25 50 km at sub-district level only. Information visualized on this map is not to be considered complete or geographically correct. -

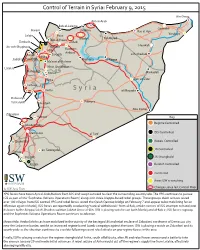

Control of Terrain in Syria: February 9, 2015

Control of Terrain in Syria: February 9, 2015 Ain-Diwar Ayn al-Arab Bab al-Salama Qamishli Harem Jarablus Ras al-Ayn Yarubiya Salqin Azaz Tal Abyad Bab al-Hawa Manbij Darkush al-Bab Jisr ash-Shughour Aleppo Hasakah Idlib Kuweiris Airbase Kasab Saraqib ash-Shadadi Ariha Jabal al-Zawiyah Maskana ar-Raqqa Ma’arat al-Nu’man Latakia Khan Sheikhoun Mahardeh Morek Markadeh Hama Deir ez-Zour Tartous Homs S y r i a al-Mayadin Dabussiya Palmyra Tal Kalakh Jussiyeh Abu Kamal Zabadani Yabrud Key Regime Controlled Jdaidet-Yabus ISIS Controlled Damascus al-Tanf Quneitra Rebels Controlled as-Suwayda JN Controlled Deraa Nassib JN Stronghold Jizzah Kurdish Controlled Contested Areas ISW is watching Changes since last Control Map by ISW Syria Team YPG forces have taken Ayn al-Arab/Kobani from ISIS and swept outward to clear the surrounding countryside. The YPG continues to pursue ISIS as part of the “Euphrates Volcano Operations Room,” along with three Aleppo-based rebel groups. These groups claim to have seized over 100 villages from ISIS control. YPG and rebel forces seized the Qarah Qawzaq bridge on February 7 and appear to be mobilizing for an oensive against Manbij. ISIS forces are reportedly conducting “tactical withdrawals” from al-Bab, amidst rumors of ISIS attempts to hand over its bases to the Aleppo Sala Jihadist coalition Jabhat Ansar al-Din. ISW is placing watches on both Manbij and al-Bab as ISIS forces regroup and the Euphrates Volcano Operations Room continues to advance. Meanwhile, Hezbollah forces have mobilized in the vicinity of the besieged JN and rebel enclave of Zabadani, northwest of Damascus city near the Lebanese border, amidst an increased regime barrel bomb campaign against the town. -

Ar-Raqqa Governorate, April 2018 OVERALL FINDINGS1

Ar-Raqqa Governorate, April 2018 Humanitarian Situation Overview in Syria (HSOS) OVERALL FINDINGS1 Coverage Ar-Raqqa governorate is located in northeast Syria. The Euphrates River flows through the governorate TURKEY and into the Al-Thawrah Dam, the largest hydroelectric dam providing electricity in Syria, although years of Tell Abiad conflict have limited its ability to generate electricity. Since the conflict over Ar-Raqqa city ended in October AL-HASAKEH 2017, electricity services have been mostly unavailable. However, recent repairs to the Al Furosya electric ALEPPO station resulted in 72% of the assessed communities relying primarily on the electricity network in April. Ein Issa Suluk In over half of assessed communities, Key Informants (KIs) estimated that 76-100% of the pre-conflict population remained. However, 7 communities in Ar- Raqqa and Ein Issa sub-districts, reported less than 50% of pre-conflict populations remained. The majority of the assessed communities reported a presence of IDPs, approximately 90,037 IDPs in total. Most of these IDPs resided in Al-Thawra community, which has experienced two large IDP influxes in the past four months. In April, approximately 25 spontaneous Ar-Raqqa refugee returns from Lebanon and Jordan were reported in Jurneyyeh community (Ath-Thawrah district). Jurneyyeh The most commonly reported reasons for return were to reunite with family and protection concerns in host Karama communities2. Ar-Raqqa KIs reported that healthcare was one of the top priority needs in April. Reflective of this, 25 of the Al-Thawrah assessed communities reported that there were no health facilities available in the area, and only 3 of the Maadan assessed communities reported having functioning pre-conflict hospitals. -

Deir Ez Zor Governorate

“THIS IS MORE THAN VIOLENCE”: AN OVERVIEW OF CHILDREN’S PROTECTION NEEDS IN SYRIA Deir Ez Zor PROTECTION SEVERITY RANKING BY SUB-DISTRICT Severity ranking by sub-districts considered 3 indicators: i) % of IDPs in the population; Kisreh ii) conflict incidents weighted according to Tabni the extent of impact; and Sur iii) population in hard-to-reach communities. Deir-ez-Zor Khasham Basira Deir-ez-Zor Muhasan Thiban Sve anks Al Mayadin Hajin N oblem Ashara oblem Jalaa Moderat oblem Susat Abu Kamal oblem Svere oblem Cri�cal problem Catrastrophic problem POPULATION DATA Number of 0-4 Years 5-14 Years 15-17 Years Locations Total Children % of Children Total Population Communities 136 Overall Population 12% 27% 6% 400K 45% 895K PIN 12% 25% 8% 329K 45% 740K IDP 12% 27% 6% 68K 45% 152K Hard to Reach Locations 135 12% 27% 6% 285K 45% 638K Besieged Locations 0 Military Encircled Locations 1 12% 27% 6% 37K 45% 84K * es�mates to support humanitarian planning processes only SUMMARY OF FINDINGS 131 communities (96%) were assessed in Deir-ez-Zor issue of concern. Adolescent boys (70%) followed by adolescent governorate. girls (8%) were considered most affected child population groups. • In 7 per cent of assessed communities, respondents • In 100 percent of assessed communities respondents reported reported child labour preventing school attendance was that family violence was an issue of concern. Adolescent girls an issue of concern. Both adolescent boys in different age (100%) followed by both girls <12 years and boys <12 years (99%) groups 15-17 and 12-14 years were considered equally were considered the most affected child population groups. -

S/2019/321 Security Council

United Nations S/2019/321 Security Council Distr.: General 16 April 2019 Original: English Implementation of Security Council resolutions 2139 (2014), 2165 (2014), 2191 (2014), 2258 (2015), 2332 (2016), 2393 (2017), 2401 (2018) and 2449 (2018) Report of the Secretary-General I. Introduction 1. The present report is the sixtieth submitted pursuant to paragraph 17 of Security Council resolution 2139 (2014), paragraph 10 of resolution 2165 (2014), paragraph 5 of resolution 2191 (2014), paragraph 5 of resolution 2258 (2015), paragraph 5 of resolution 2332 (2016), paragraph 6 of resolution 2393 (2017),paragraph 12 of resolution 2401 (2018) and paragraph 6 of resolution 2449 (2018), in the last of which the Council requested the Secretary-General to provide a report at least every 60 days, on the implementation of the resolutions by all parties to the conflict in the Syrian Arab Republic. 2. The information contained herein is based on data available to agencies of the United Nations system and obtained from the Government of the Syrian Arab Republic and other relevant sources. Data from agencies of the United Nations system on their humanitarian deliveries have been reported for February and March 2019. II. Major developments Box 1 Key points: February and March 2019 1. Large numbers of civilians were reportedly killed and injured in Baghuz and surrounding areas in south-eastern Dayr al-Zawr Governorate as a result of air strikes and intense fighting between the Syrian Democratic Forces and Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant. From 4 December 2018 through the end of March 2019, more than 63,500 people were displaced out of the area to the Hawl camp in Hasakah Governorate. -

Explosive Device Response Operations

EXPLOSIVE DEVICE RESPONSE OPERATIONS Capability Definition Explosive Device Response Operations is the capability to coordinate, direct, and conduct improvised explosive device (IED) response after initial alert and notification. Coordinate intelligence fusion and RESPOND MISSION: EXPLOSIVE DE analysis, information collection, and threat recognition, assess the situation and conduct appropriate Render Safe Procedures (RSP). Conduct searches for additional devices and coordinate overall efforts to mitigate chemical, biological, radiological, nuclear, and explosive (CBRNE) threat to the incident site. Outcome Threat assessments are conducted, the explosive and/or hazardous devices are rendered safe, and the area is cleared of hazards. Measures are implemented in the following priority order: ensure public safety; safeguard the officers on the scene (including the bomb technician); collect and preserve evidence; protect and preserve public and private property; and restore public services. Relationship to National Response Plan Emergency Support Function (ESF)/Annex This capability supports the following Emergency Support Functions (ESFs): Terrorism Incident Law Enforcement and Investigation Annex ESF #10: Oil and Hazardous Materials Response ESF #13: Public Safety and Security VICE RESPONSE OPERATIONS Preparedness Tasks and Measures/Metrics Activity: Develop and Maintain Plans, Procedures, Programs, and Systems Critical Tasks Res.B2c 1.1 Develop, distribute, and maintain National Guidelines for Bomb Technicians Develop effective procedures -

Situation Report: WHO Syria, Week 19-20, 2019

WHO Syria: SITUATION REPORT Weeks 32 – 33 (2 – 15 August), 2019 I. General Development, Political and Security Situation (22 June - 4 July), 2019 The security situation in the country remains volatile and unstable. The main hot spots remain Daraa, Al- Hassakah, Deir Ezzor, Latakia, Hama, Aleppo and Idlib governorates. The security situation in Idlib and North rural Hama witnessed a notable escalation in the military activities between SAA and NSAGs, with SAA advancement in the area. Syrian government forces, supported by fighters from allied popular defense groups, have taken control of a number of villages in the southern countryside of the northwestern province of Idlib, reaching the outskirts of a major stronghold of foreign-sponsored Takfiri militants there The Southern area, particularly in Daraa Governorate, experienced multiple attacks targeting SAA soldiers . The security situation in the Central area remains tense and affected by the ongoing armed conflict in North rural Hama. The exchange of shelling between SAA and NSAGs witnessed a notable increase resulting in a high number of casualties among civilians. The threat of ERWs, UXOs and Landmines is still of concern in the central area. Two children were killed, and three others were seriously injured as a result of a landmine explosion in Hawsh Haju town of North rural Homs. The general situation in the coastal area is likely to remain calm. However, SAA military operations are expected to continue in North rural Latakia and asymmetric attacks in the form of IEDs, PBIEDs, and VBIEDs cannot be ruled out. II. Key Health Issues Response to Al Hol camp: The Security situation is still considered as unstable inside the camp due to the stress caused by the deplorable and unbearable living conditions the inhabitants of the camp have been experiencing . -

Syria SITREP Map 07

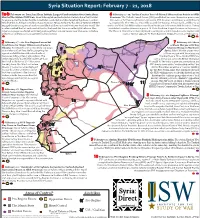

Syria Situation Report: February 7 - 21, 2018 1a-b February 10: Israel and Iran Initiate Largest Confrontation Over Syria Since 6 February 9 - 15: Turkey Creates Two Additional Observation Points in Idlib Start of the Syrian Civil War: Israel intercepted and destroyed an Iranian drone that violated Province: The Turkish Armed Forces (TSK) established two new observation points near its airspace over the Golan Heights. Israel later conducted airstrikes targeting the drone’s control the towns of Tal Tuqan and Surman in Eastern Idlib Province on February 9 and February vehicle at the T4 Airbase in Eastern Homs Province. Syrian Surface-to-Air Missile Systems (SAMS) 15, respectively. The TSK also reportedly scouted the Taftanaz Airbase north of Idlib City as engaged the returning aircraft and successfully shot down an Israeli F-16 over Northern Israel. The well as the Wadi Deif Military Base near Khan Sheikhoun in Southern Idlib Province. Turkey incident marked the first such combat loss for the Israeli Air Force since the 1982 Lebanon War. established a similar observation post at Al-Eis in Southern Aleppo Province on February 5. Israel in response conducted airstrikes targeting at least a dozen targets near Damascus including The Russian Armed Forces later deployed a contingent of military police to the regime-held at least four military positions operated by Iran in Syria. town of Hadher opposite Al-Eis in Southern Aleppo Province on February 14. 2 February 17 - 20: Pro-Regime Forces Set Qamishli 7 February 18: Ahrar Conditions for Major Offensive in Eastern a-Sham Merges with Key Ghouta: Pro-regime forces intensified a campaign 9 Islamist Group in Northern of airstrikes and artillery shelling targeting the 8 Syria: Salafi-Jihadist group Ahrar opposition-held Eastern Ghouta suburbs of Al-Hasakah a-Sham merged with Islamist group Damascus, killing at least 250 civilians. -

UNHCR's Operational Update: January-March 2019, English

OPERATIONAL UPDATE Syria January -March 2019 As of end of March, UNHCR In February, UNHCR participated in Since December a major emergency concluded its winterization the largest ever humanitarian in North East Syria led to thousands of programme with the distribution convoy providing life-saving people fleeing Hajin to Al-Hol camp. of 1,553,188 winterized humanitarian assistance to some UNHCR is providing core relief items to 1,163,494 individuals/ 40,000 displaced people at the items, shelter and protection 241,870 families in 13 governorates in Rukban ‘makeshift’ settlement in support for the current population Syria. south-eastern Syria, on the border which exceeds 73,000 individuals. with Jordan. HUMANITARIAN SNAPSHOT 11.7 million FUNDING (AS OF 16 APRIL 2019) people in need of humanitarian assistance USD 624.4 million requested for the Syria Operation 13.2 million Funded 14% people in need of protection interventions 87.4 million 11.3 million people in need of health assistance 4.7 million people in need of shelter Unfunded 86% 4.4 million 537 million people in need of core relief items POPULATION OF CONCERN Internally Displaced Persons Internally displaced persons 6.2 million Returnees Syrian displaced returnees 2018 1.4 million* Syrian refugee returnees 2018 56,047** Syrian refugee returnees 2019 21,575*** Refugees and Asylum seekers Current population 32,289**** Total urban refugees 17,832 Total asylum seekers 14,457 Camp population 30,529***** High Commissioner meets with families in Souran in Rural * OCHA, December 2018 Hama that have returned to their homes and received shelter ** UNHCR, December 2018 *** UNHCR, March 2019 assistance from UNHCR.