Development of a Maternity Hospital Classification for Use in Perinatal Research

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Zealand Out-Of-Hospital Acute Stroke Destination Policy Northland and Auckland Areas

New Zealand Out-of-Hospital Acute Stroke Destination Policy Northland and Auckland Areas This policy is for the use of clinical personnel when determining the destination hospital for patients with an acute stroke in the out-of-hospital setting in the Northland and Auckland areas of New Zealand. It has been developed by the Northern Region Stroke Network in conjunction with the National Stroke Network and the Ambulance Sector. Publication date October 2020 Acute Stroke Destination Flowchart: Auckland Area Does the patient have signs or symptoms Stroke is unlikely, treat of an acute stroke? NO appropriately without YES using this policy. Perform additional screening using the PASTA tool Will the patient arrive at: NO NO A stroke hospital within 4 hours Does the patient Transport to the of symptom onset, or meet ‘wake-up’ most appropriate Auckland City Hospital within stroke criteria?1 hospital. 6 hours of symptom onset? YES YES Transport to the catchment YES PASTA positive? NO area hospital and notify hospital personnel of the Patient will arrive in ED 0800–1600, Mon–Fri following information: PASTA results and Transport to the most appropriate stroke hospital and notify hospital personnel as below: FAST results and Time of symptom onset and North Shore Hospital. Auckland City Hospital. NHI number Waitakere Hospital. Middlemore Hospital. Out of hours If the patient is in the North Shore Hospital, Notify hospital personnel Waitakere Hospital or Middlemore Hospital ASAP and provide the catchment: following information as a – Phone the on-call neurologist at Auckland City minimum: Hospital on 0800 1 PASTA as per the PASTA tool. -

Community to Hospital Shuttle Service

Is other transport assistance Total Mobility Scheme available? The Total Mobility Scheme is a subsidised taxi Best Care for Everyone Yes, there are several options available to those service. The scheme is available to people who qualify. who are unable to use public transport due to the nature of their disability. It works using vouchers that give a 50% discount on normal National Travel Assistance (NTA) Policy taxi fares. The scheme is part-funded by the NTA helps with travel costs for people who New Zealand Transport Agency and managed need to travel often or for long distances to get by the local authorities. to specialist health or disability services. The MAXX Contact Centre can provide the To receive this service, you need to be referred contact details for disability agencies that by your specialist (not your family doctor) to process applications. Call 09 366 6400 see another specialist or to receive specialist services. Both the specialists must be part of a St John Health Shuttle - Waitakere service funded by the government. The St John Health Shuttle provides safe, For example, this could be a renal dialysis reliable transport for Waitakere City residents centre, a specialist cancer service or a child to and from appointments with family doctors, development service. The rules are different treatment at Waitakere Hospital outpatient for children and adults, and for those holding clinics, visits to specialists, and transport to a Community Services Card. Sometimes, a and from minor day surgery. The vehicle is support person can receive assistance too. wheelchair accessible. The service operates Monday to Friday for appointments between How do I contact NTA? 9.30am and 2pm. -

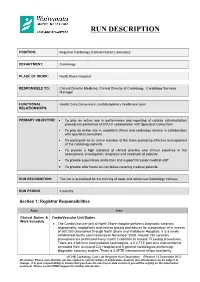

Run Description

RUN DESCRIPTION POSITION: Registrar Cardiology Catheterization Laboratory DEPARTMENT: Cardiology PLACE OF WORK: North Shore Hospital RESPONSIBLE TO: Clinical Director Medicine, Clinical Director of Cardiology, Cardiology Services Manager FUNCTIONAL Health Care Consumers, multidisciplinary healthcare team RELATIONSHIPS: PRIMARY OBJECTIVE: • To play an active role in performance and reporting of cardiac catheterization procedures performed at CVU in collaboration with Specialist Consultant. • To play an active role in outpatient clinics and cardiology service in collaboration with specialist consultant • To participate as an active member of the team promoting effective management of the cardiology patients. • To provide a high standard of clinical practice and clinical expertise in the assessment, investigation, diagnosis and treatment of patients. • To provide supervision, instruction and support for junior medical staff. • To provide after hours on-call duties covering medical patients. RUN RECOGNITION: The run is accredited for the training of basic and advanced Cardiology trainees RUN PERIOD 6 months Section 1: Registrar Responsibilities Area Area Clinical Duties & CardioVascular Unit Duties Work Schedule • The CardioVascular unit at North Shore Hospital performs diagnostic coronary angiography, angioplasty and cardiac pacing procedures for a population of in excess of 500,000 channelled through North Shore and Waitakere Hospitals. It is a newly established facility commissioned in November 2008. Around 150 coronary procedures are performed every month in addition to around 15 pacing procedures. There are 2 full-time interventional cardiologists, a 0.2 FTE part-time interventionist seconded from Auckland City Hospital and 5 general cardiologists performing diagnostic coronary studies. There is 0.5FTE interventional fellow availability. WDHB Cardiology Cath Lab Registrar Run Description – Effective 12 December 2011 Disclaimer: Please note that this run description is current at time of publication, however this information can be subject to change. -

Hand Surgery Fellowships

HAND SURGERY FELLOWSHIPS VICTORIA Victorian Hand Surgery Associates Fellowship A Fellowship in hand surgery is available for a 6 or 12 month period for surgeons who have successfully completed their basic surgical training and are interest in furthering their training in hand surgery. The successful candidate will work with the surgeons of the Victorian Hand Surgery Associates in private practice and with the Plastic and Hand Surgery Units of St.Vincent’s Public Hospital in Melbourne. The fellowship involves pre-operative management of a wide variety of hand conditions. These would include elective and emergency conditions including microsurgery reconstruction and replantation. Some exposure to paediatric hand surgery is available with visits to the Royal Children’s Hospital. The candidate would be expected to be involved in the day to day running to the hand service including undergraduate and post-graduate teaching, journal club, audit meetings, clinical and radiology conferences and ongoing clinical research. The candidate would also attend regular meetings of the Victorian Hand Surgery Society. A monthly stipend is available for unfunded fellows. For further details, interested candidates should contact: Mr A.Berger Suite 1 Level 3 Healy Wing St.Vincent’s Public Hospital 41 Victoria Parade Fitzroy 3065 Victoria Australia Email: [email protected] Hand Surgery Fellowship position at Dandenong Hospital Applications are invited for a Hand Surgery Fellowship position at Dandenong Hospital, Southern Health, Melbourne. This position is suitable for a candidate preparing for a career in hand surgery. The successful candidate will be involved in emergency and elective cases, oncall from the emergency department and outpatient care. -

Cavendish Radiology Final Version.Pptx

Cavendish Clinic Radiology Cavendish Clinic Specialist Centre • 11 Orthopaedic surgeons • Many are also associated with Ascot Office Park • Close relationship with Middlemore Hospital • State of the art facility with adjacent high quality radiology • Minor procedure day theatre • Plaster room • High speed internet Cavendish Clinic Location • Conveniently located on Cavendish Dr between SH1 and SH20 • Dedicated off ramps from SH20 from both north and south • Te Irirangi Dr off ramp going south on SH1 • 12 minutes from Newmarket • 6 minutes from Onehunga on S20 • 24,000 vehicles per day • Excellent parking and controlled intersection • Close to Superclinic • High quality cafe physio Orthopaedic Surgeons Radiology GP Imaging Services • Philips Digital Diagnost x ray • Philips Epic Ultrasound • Siemens 32 slice CT • Philips 3Tesla Ingenia MRI • Spinal and musculoskeletal interventional service. • Excellent IT support for referrers with Intelerad PACS. Cavendish Clinic Radiology • Established to provide integrated high quality diagnostic and interventional musculoskeletal radiology to South Auckland • Patient convenience a major driver • Mirror image of SRG Greenlane with no difference in service and expertise • Full time radiologist attendance • All radiologists subspecialty trained and work at major Auckland teaching hospitals • All sonographers musculoskeletal trained under direct onsite radiologist supervision • Also perform wide range of general radiology Referrer Resources • PACS • SRG Website • IT support including onsite if required • Excellent radiologist access • Electronic referral soon available Key Staff • Lynn Kurtovich - Administration Manager - Formerly manager at Manukau MRI - Desiree Mulders - Head MRT - Has been at SRG for 7 years - Olwyn Clarke - Sonographer - Also works art Middlemore Radiologists • Quentin Reeves - Auckland City Hospital • Richard Gee - North Shore Hospital • Philip Clark - North Shore Hospital • Lucinda Boyer - Auckland City Hospital • Francessa Wilson - Starship Hospital . -

New Zealand Hospitals

New Zealand Hospitals North Island hospitals Whangarei Hospital Postal Address Private Bag 9742 Postcode 0148 Street Address Maunu Road Whangarei 0110 Tel. (09) 430 4100 Fax (09) 430 4115 North Shore Hospital Postal Address Private Bag 93 503 Takapuna Postcode North Shore City 0740 Street Address Cnr Shakespeare & Taharoto Roads Takapuna North Shore City 0622 Tel. (09) 486 8900 Fax (09) 486 8908 Waitakere Hospital Postal Address Private Bag 93 115 Henderson Postcode Waitakere 0610 Street Address 55-75 Lincoln Road Henderson Waitakere 0650 Tel. (09) 839 0000 Fax (09) 837 6605 Auckland City Hospital Postal Address Private Bag 92 024 Postcode Auckland 1142 Street Address 2 Park Road Grafton Auckland 1023 Tel. (09) 367 0000 Fax (09) 375 7069 Waikato Hospital Postal Address Private Bag 3200 Postcode Hamilton 3240 Street Address Pembroke Street Hamilton 3240 Tel. (07) 839 8899 Fax (07) 839 8683 Tauranga Hospital Postal Address Private Bag 12 024 Postcode Tauranga 3143 Street Address Cameron Road Tauranga 3110 Tel. (07) 579 8000 Fax (07) 579 8506 Whakatane Hospital Postal Address PO Box 241 Postcode Whakatane 3120 Street Address Stewart Street Whakatane 3120 Tel. (07) 307 8999 Fax (07) 307 0451 Rotorua Hospital Postal Address Private Bag 3023 Postcode Rotorua 3046 Street Address Pukeroa Street Rotorua 3010 Tel. (07) 348 1199 Fax (07) 349 7897 Taupo Hospital Postal Address PO Box 841 Postcode Taupo 3351 Street Address Kotare Street Taupo 3330 Tel. (07) 378 8100 Fax (07) 378 2033 Gisborne Hospital Postal Address Private Bag 7001 Postcode Gisborne 4040 Street Address 421 Ormond Road Gisborne 4010 Tel. (06) 869 0500 Fax (06) 869 0522 Taranaki Base Hospital Postal Address PO Box 2016 Postcode New Plymouth 4310 Street Address David Street New Plymouth 4310 Tel. -

Hospital-Review-2021.Pdf

NZRDA Hospital REVIEW JULY 2021 Get in touch Unit E, Building 3 195 Main Highway, Ellerslie, Auckland 1051 P: 09 526 0280 www.nzrda.org.nz [email protected] facebook.com/nzresidentdoctor 2 Contents Introduction . 4 Trainee Interns . 5 Northland . 6 Whangarei Hospital Waitemata . 8 North Shore & Waitakere Hospitals Auckland ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 12 Auckland Hospital & Starship Counties Manukau . 16 Middlemore Hospital Waikato ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 19 Waikato Hospital Bay of Plenty ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������ 22 Tauranga & Whakatane Hospitals Lakes ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������25 Rotorua & Beyond Hastings . 27 Hawke’s Bay Hospital Midcentral ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������30 Palmerston North Hospital Taranaki �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 32 Taranaki Base Hospital Whanganui . 35 Whanganui Hospital Wairarapa . 37 Wairarapa Hospital Hutt Valley . 39 Hutt Hospital Capital & Coast . 41 Wellington Hospital & Kenepuru Nelson Marlborough ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������44 -

Waitemata DHB's 'Package of Care' Elective Surgery Model: a Costly Experiment?

Waitemata District Health Board’s ‘Package of Care’ Elective Surgery Model: A costly experiment? Issue 8 | August 2013 Previous Issues of Health Dialogue Issue 1 Workforce Planning April 1999 Issue 2 Sexual Health Services March 1999 Issue 3 Managed Care and the Capital Coast Health Draft Business Plan June 1999 Issue 4 Superannuation for Senior Doctors in DHBs April 2002 Issue 5 Professionalism in a Modern Health System June 2003 Issue 6 The Future of the Leaking Bucket November 2009 Issue 7 A Public Hospital for 2026: Queenstown June 2011 Preface A key role of the Association of Salaried Medical Specialists (ASMS or the Association) over the years has been to bring important health sector issues to the attention of its members, the public in general and other stakeholders. One means of fulfilling this role has been the publication of Health Dialogue, an occasional paper produced to stimulate debate and policy discussion on a particular current issue. In this Health Dialogue we examine a controversial ‘model of care’ that has been introduced in Waitemata District Health Board’s new stand-alone Elective Surgery Centre (ESC). Dedicated elective surgical centres, separated from acute and emergency surgery, are recognised both internationally and in New Zealand as both appropriate and beneficial under certain conditions. The controversy is over the particular development and application of this concept in Waitemata, using a slogan-like ‘package of care’ model. This ‘package of care’ application has radically changed the way elective surgery services are provided at Waitemata DHB and it has been suggested the model could be introduced in other DHBs. -

New Zealand Doctors

New Zealand Doctors NORTHLAND DHB WAITEMATA DHB AUCKLAND DHB COUNTIES MANUKAU DHB BAY OF PLENTY DHB WAIKATO DHB LAKES DHB TAIRAWHITI DHB TARANAKI DHB HAWKE’S BAY DHB WHANGANUI DHB MIDCENTRAL DHB CAPITAL & COAST DHB WAIRARAPA DHB NELSON MARLBOROUGH DHB HUTT VALLEY DHB WEST COAST DHB CANTERBURY DHB SOUTH CANTERBURY DHB SOUTHERN DHB July1 2015 www.kiwihealthjobs.com Contents Northland District Health Board ........................................................................................................................................... 3 Waitemata District Health Board ..........................................................................................................................................6 Auckland District Health Board .............................................................................................................................................9 Counties Manukau District Health Board ........................................................................................................................ 12 Waikato District Health Board ..............................................................................................................................................15 Bay of Plenty District Health Board ...................................................................................................................................16 Lakes District Health Board ...................................................................................................................................................18 -

Royal North Shore Hospital Visitor Map

Royal North Shore Hospital Visitor Map Updated November 2015 Welcome to RNSH P1 best for staff - ñ 15 min drop-off and pick-up parking is available visitor parking also available. at the Main Entry & Emergency. North ñ Best parking for patients & visitors is P2. Shore ñ Parking Office is in P2 car park. ñ Meter parking also available. Private ROAD RESERVE Hospital WESTBOURNE ST WESTBOURNE ST Chapel 3 Kolling Clinical 8 P2 best for 6 Building 5 Services Herbert St Clinic patient, visitor & Building disabled parking Level 3 link Access road Parking One Ofce way P2 only Main Hospital Ambulatory entry Acute Services Building Care Centre Level 3 via 1 Health Centre main entry RNS Community 4 Douglas 2 Building EILEEN ST DOUGLAS BUILDING 30 Level 2 Pain HERBERT ST Management Level 3 Carer Centre 35 support service and 4P accommodation Oval Oval ROAD RESERVE ST LEONARDS Complimentary map proudly STATION provided by www.infrashore.com.au PACIFIC HWY KEY P2 Main car park ñ Patients and visitors please use P2 car park. Emergency ñ Concession card holders use P2 car park. Disabled parking ñ Meter parking is available in marked areas. Main Entry ñ Disabled parking is available in all meter parking areas and multi-storey car Meter parking parks. Disabled parking permit must be displayed if you’re parking in a Bus 1P 1 hour parking disabled bay. Ask for a disabled parking information map at the Information Taxi Desk or Parking Office, or visit the website. 5P Up to 5 hours parking ñ Parking fees apply at RNSH and adjacent Council areas. -

Fellowships – Updated July 2 2021

New Zealand based Fellowships – updated July 2 2021 NORTHLAND: Whangarei Shoulder & Knee Fellowship – 6 months commencing August The fellow receives funding & It’s specifically directed towards newly qualified NZ orthopaedic surgeons. Contact is Marc Hirner AUCKLAND: Trauma Fellowship - 6 months commencing February and August Arthroplasty Fellowship - 12 months commencing August 2 x Spine Fellowships - 12 months commencing July Auckland City Hospital Applicants for the above four Fellowships should contact Cyndy Brown: [email protected] 2 X Arthroplasty Fellowships - 12 months commencing June and December North Shore Hospital Takapuna Contact: Mr Rob Sharp Shoulder & Elbow Fellowship - 6 months commencing January or July North Shore Hospital Takapuna The contact is Mr Peter Poon – For more details please email: [email protected] 2 x Paediatric Orthopaedic Surgery Fellowships - 12 months commencing August Starship Children’s Hospital The Paediatric Orthopedic Surgery Fellowships at Starship Children’s Hospital provide a broad exposure to all subspecialties of paediatric orthopaedics, including upper extremity, hip, lower extremity, foot and ankle, trauma, oncology, skeletal dysplasias, neuromuscular disorders and congenital deformities/malformations. There is minimal exposure to paediatric spine surgery, which is predominantly covered by the Starship Paediatric Spine Surgery Fellow. This one-year clinical fellowship programme commences in August and revolves around a mentorship model, with fellows undertaking defined rotations with paediatric orthopaedic surgeons in the clinic and operating room. Fellows take senior call as part of a two-tier on call roster, undertake a central role in clinical conferences and registrar teaching, and are expected to undertake at least one significant research project during their fellowship year. -

Inquiry Into the Royal North Shore Hospital

Submission No 30 INQUIRY INTO THE ROYAL NORTH SHORE HOSPITAL Organisation: Section of Cardiology, Royal North Shore Hospital Name: Professor Stephen Hunyor Position: Chairman Date Received: 12/11/2007 Submission to The Joint Select Committee of the NSW Parliament (established to enquire into the quality of care for patients at Royal North Shore Hospital (RNSH)) by the 18 Members of the Section and Department of Cardiology - RNSH Doctors: Eddie Barin, Chris Barnes, Peter Caspari, Christopher Choong, Rupert Edwards, John Gunning (Head of Department of Cardiology), Peter Hansen, Kevin Hellestrand, Logan Kanagaratnam, Fred Nasser, Gregory Nelson, Michael Ward, Harvey Washington, David Whalley, Assoc Prof: Alexandra Bune Professors: Stephen Hunyor (Chairman of the Section of Cardiology), Helge Rasmussen, Geoffrey Tofler, [email protected] 1 of 28 CONTENTS Page Executive Summary 3-4 1(a) Clinical Management • Unresponsiveness of Systems 5 Systems @ RNSH • Medical Staff Input • Precipitous Fall in Standards @RNSH 5 • Lack of Acknowledgement 7 7 • Clinical Reference Group Governance • “Corporate Memory” @ RNSH 8 • Hospital Boards-Accountability, Transparency 8 • The Victorian Governance Model 9 • Budgeting 9 • RNSH as 3°&4° Referral Centre of Excellence 10 RECOMMENDATIONS (1-10) 10 1(b) Clinical Staffing & • Staff Morale 12 Organisation Structures @ • The Workforce @ RNSH 12 RSNH • Senior Medical Staff - mix of Staff Specialists and VMOs - Medical Staff Council & disenfranchisement - loss of Medical Staff to Private Hospitals RECOMMENDATIONS