ZM82 565-576 Dance.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Radiation and Decline of Endodontid Land Snails in Makatea, French Polynesia

Zootaxa 3772 (1): 001–068 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Monograph ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2014 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.3772.1.1 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:1A1578DD-4B10-4F70-8CB6-03B0ED07AB68 ZOOTAXA 3772 Radiation and decline of endodontid land snails in Makatea, French Polynesia ANDRÉ F. SARTORI1, OLIVIER GARGOMINY2 & BENOÎT FONTAINE3 Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, 55 rue Buffon, 75005 Paris, France. E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] Magnolia Press Auckland, New Zealand Accepted by J. Nekola: 17 Dec. 2013; published: 3 Mar. 2014 ANDRÉ F. SARTORI, OLIVIER GARGOMINY & BENOÎT FONTAINE Radiation and decline of endodontid land snails in Makatea, French Polynesia (Zootaxa 3772) 68 pp.; 30 cm. 3 Mar. 2014 ISBN 978-1-77557-348-7 (paperback) ISBN 978-1-77557-349-4 (Online edition) FIRST PUBLISHED IN 2014 BY Magnolia Press P.O. Box 41-383 Auckland 1346 New Zealand e-mail: [email protected] http://www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ © 2014 Magnolia Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, transmitted or disseminated, in any form, or by any means, without prior written permission from the publisher, to whom all requests to reproduce copyright material should be directed in writing. This authorization does not extend to any other kind of copying, by any means, in any form, and for any purpose other than private research use. ISSN 1175-5326 (Print edition) ISSN 1175-5334 (Online edition) 2 · Zootaxa 3772 (1) © 2014 Magnolia Press SARTORI ET AL. -

High Level Environmental Screening Study for Offshore Wind Farm Developments – Marine Habitats and Species Project

High Level Environmental Screening Study for Offshore Wind Farm Developments – Marine Habitats and Species Project AEA Technology, Environment Contract: W/35/00632/00/00 For: The Department of Trade and Industry New & Renewable Energy Programme Report issued 30 August 2002 (Version with minor corrections 16 September 2002) Keith Hiscock, Harvey Tyler-Walters and Hugh Jones Reference: Hiscock, K., Tyler-Walters, H. & Jones, H. 2002. High Level Environmental Screening Study for Offshore Wind Farm Developments – Marine Habitats and Species Project. Report from the Marine Biological Association to The Department of Trade and Industry New & Renewable Energy Programme. (AEA Technology, Environment Contract: W/35/00632/00/00.) Correspondence: Dr. K. Hiscock, The Laboratory, Citadel Hill, Plymouth, PL1 2PB. [email protected] High level environmental screening study for offshore wind farm developments – marine habitats and species ii High level environmental screening study for offshore wind farm developments – marine habitats and species Title: High Level Environmental Screening Study for Offshore Wind Farm Developments – Marine Habitats and Species Project. Contract Report: W/35/00632/00/00. Client: Department of Trade and Industry (New & Renewable Energy Programme) Contract management: AEA Technology, Environment. Date of contract issue: 22/07/2002 Level of report issue: Final Confidentiality: Distribution at discretion of DTI before Consultation report published then no restriction. Distribution: Two copies and electronic file to DTI (Mr S. Payne, Offshore Renewables Planning). One copy to MBA library. Prepared by: Dr. K. Hiscock, Dr. H. Tyler-Walters & Hugh Jones Authorization: Project Director: Dr. Keith Hiscock Date: Signature: MBA Director: Prof. S. Hawkins Date: Signature: This report can be referred to as follows: Hiscock, K., Tyler-Walters, H. -

A Radical Solution: the Phylogeny of the Nudibranch Family Fionidae

RESEARCH ARTICLE A Radical Solution: The Phylogeny of the Nudibranch Family Fionidae Kristen Cella1, Leila Carmona2*, Irina Ekimova3,4, Anton Chichvarkhin3,5, Dimitry Schepetov6, Terrence M. Gosliner1 1 Department of Invertebrate Zoology, California Academy of Sciences, San Francisco, California, United States of America, 2 Department of Marine Sciences, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden, 3 Far Eastern Federal University, Vladivostok, Russia, 4 Biological Faculty, Moscow State University, Moscow, Russia, 5 A.V. Zhirmunsky Instutute of Marine Biology, Russian Academy of Sciences, Vladivostok, Russia, 6 National Research University Higher School of Economics, Moscow, Russia a11111 * [email protected] Abstract Tergipedidae represents a diverse and successful group of aeolid nudibranchs, with approx- imately 200 species distributed throughout most marine ecosystems and spanning all bio- OPEN ACCESS geographical regions of the oceans. However, the systematics of this family remains poorly Citation: Cella K, Carmona L, Ekimova I, understood since no modern phylogenetic study has been undertaken to support any of the Chichvarkhin A, Schepetov D, Gosliner TM (2016) A Radical Solution: The Phylogeny of the proposed classifications. The present study is the first molecular phylogeny of Tergipedidae Nudibranch Family Fionidae. PLoS ONE 11(12): based on partial sequences of two mitochondrial (COI and 16S) genes and one nuclear e0167800. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0167800 gene (H3). Maximum likelihood, maximum parsimony and Bayesian analysis were con- Editor: Geerat J. Vermeij, University of California, ducted in order to elucidate the systematics of this family. Our results do not recover the tra- UNITED STATES ditional Tergipedidae as monophyletic, since it belongs to a larger clade that includes the Received: July 7, 2016 families Eubranchidae, Fionidae and Calmidae. -

E Urban Sanctuary Algae and Marine Invertebrates of Ricketts Point Marine Sanctuary

!e Urban Sanctuary Algae and Marine Invertebrates of Ricketts Point Marine Sanctuary Jessica Reeves & John Buckeridge Published by: Greypath Productions Marine Care Ricketts Point PO Box 7356, Beaumaris 3193 Copyright © 2012 Marine Care Ricketts Point !is work is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission of the publisher. Photographs remain copyright of the individual photographers listed. ISBN 978-0-9804483-5-1 Designed and typeset by Anthony Bright Edited by Alison Vaughan Printed by Hawker Brownlow Education Cheltenham, Victoria Cover photo: Rocky reef habitat at Ricketts Point Marine Sanctuary, David Reinhard Contents Introduction v Visiting the Sanctuary vii How to use this book viii Warning viii Habitat ix Depth x Distribution x Abundance xi Reference xi A note on nomenclature xii Acknowledgements xii Species descriptions 1 Algal key 116 Marine invertebrate key 116 Glossary 118 Further reading 120 Index 122 iii Figure 1: Ricketts Point Marine Sanctuary. !e intertidal zone rocky shore platform dominated by the brown alga Hormosira banksii. Photograph: John Buckeridge. iv Introduction Most Australians live near the sea – it is part of our national psyche. We exercise in it, explore it, relax by it, "sh in it – some even paint it – but most of us simply enjoy its changing modes and its fascinating beauty. Ricketts Point Marine Sanctuary comprises 115 hectares of protected marine environment, located o# Beaumaris in Melbourne’s southeast ("gs 1–2). !e sanctuary includes the coastal waters from Table Rock Point to Quiet Corner, from the high tide mark to approximately 400 metres o#shore. -

Some Thoughts and Personal Opinions About Molluscan Scientific Names

A name is a name is a name: some thoughts and personal opinions about molluscan scientifi c names S. Peter Dance Dance, S.P. A name is a name is a name: some thoughts and personal opinions about molluscan scien- tifi c names. Zool. Med. Leiden 83 (7), 9.vii.2009: 565-576, fi gs 1-9.― ISSN 0024-0672. S.P. Dance, Cavendish House, 83 Warwick Road, Carlisle CA1 1EB, U.K. ([email protected]). Key words: Mollusca, scientifi c names. Since 1758, with the publication of Systema Naturae by Linnaeus, thousands of scientifi c names have been proposed for molluscs. The derivation and uses of many of them are here examined from various viewpoints, beginning with names based on appearance, size, vertical distribution, and location. There follow names that are amusing, inventive, ingenious, cryptic, ideal, names supposedly blasphemous, and names honouring persons and pets. Pseudo-names, diffi cult names and names that are long or short, over-used, or have sexual connotations are also examined. Pertinent quotations, taken from the non-scientifi c writings of Gertrude Stein, Lord Byron and William Shakespeare, have been incorporated for the benefi t of those who may be inclined to take scientifi c names too seriously. Introduction Posterity may remember Gertrude Stein only for ‘A rose is a rose is a rose’. The mean- ing behind this apparently meaningless statement, she said, was that a thing is what it is, the name invoking the images and emotions associated with it. One of the most cele- brated lines in twentieth-century poetry, it highlights the importance of names by a sim- ple process of repetition. -

Gastropoda: Pulmonata: Achatinellidae) 1

Published online: 29 May 2015 ISSN (online): 2376-3191 Records of the Hawaii Biological Survey for 2014. Part I: 49 Articles. Edited by Neal L. Evenhuis & Scott E. Miller. Bishop Museum Occasional Papers 116: 49 –51 (2015) Rediscovery of Auriculella pulchra Pease, 1868 (Gastropoda: Pulmonata: Achatinellidae) 1 NORINe W. Y eUNg 2, D ANIel CHUNg 3 Bishop Museum, 1525 Bernice Street, Honolulu, Hawai‘i 96817-2704, USA; emails: [email protected], [email protected] DAvID R. S ISCHO Department of Land and Natural Resources, 1151 Punchbowl Street, Rm. 325, Honolulu, Hawai‘i 96813, USA; email: [email protected] KeNNetH A. H AYeS 2,3 Howard University, 415 College Street NW, Washington, DC 20059, USA; email: [email protected] Hawaii supports one of the world’s most spectacular land snail radiations and is a diversity hotspot (Solem 1983, 1984, Cowie 1996a, b). Unfortunately, much of the Hawaiian land snail fauna has been lost, with overall extinction rates as high as ~70% (Hayes et al ., unpubl. data). However, the recent rediscovery of an extinct species provides hope that all is not lost, yet continued habitat destruction, impacts of invasive species, and climate change, necessi - tate the immediate development and deployment of effective conservation strategies to save this biodiversity treasure before it vanishes entirely (Solem 1990, Rég nier et al . 2009). Achatinellidae Auriculella pulchra Pease 1868 Notable rediscovery Auriculella pulchra (Fig. 1) belongs in the Auriculellinae, a Hawaiian endemic land snail subfamily of the Achatinellidae with 32 species (Cowie et al . 1995). It was originally described from the island of O‘ahu in 1868 and was subsequently recorded throughout the Ko‘olau Mountain range. -

Malaco Le Journal Électronique De La Malacologie Continentale Française

MalaCo Le journal électronique de la malacologie continentale française www.journal-malaco.fr MalaCo (ISSN 1778-3941) est un journal électronique gratuit, annuel ou bisannuel pour la promotion et la connaissance des mollusques continentaux de la faune de France. Equipe éditoriale Jean-Michel BICHAIN / Paris / [email protected] Xavier CUCHERAT / Audinghen / [email protected] Benoît FONTAINE / Paris / [email protected] Olivier GARGOMINY / Paris / [email protected] Vincent PRIE / Montpellier / [email protected] Les manuscrits sont à envoyer à : Journal MalaCo Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle Equipe de Malacologie Case Postale 051 55, rue Buffon 75005 Paris Ou par Email à [email protected] MalaCo est téléchargeable gratuitement sur le site : http://www.journal-malaco.fr MalaCo (ISSN 1778-3941) est une publication de l’association Caracol Association Caracol Route de Lodève 34700 Saint-Etienne-de-Gourgas JO Association n° 0034 DE 2003 Déclaration en date du 17 juillet 2003 sous le n° 2569 Journal électronique de la malacologie continentale française MalaCo Septembre 2006 ▪ numéro 3 Au total, 119 espèces et sous-espèces de mollusques, dont quatre strictement endémiques, sont recensées dans les différents habitats du Parc naturel du Mercantour (photos Olivier Gargominy, se reporter aux figures 5, 10 et 17 de l’article d’O. Gargominy & Th. Ripken). Sommaire Page 100 Éditorial Page 101 Actualités Page 102 Librairie Page 103 Brèves & News ▪ Endémisme et extinctions : systématique des Endodontidae (Mollusca, Pulmonata) de Rurutu (Iles Australes, Polynésie française) Gabrielle ZIMMERMANN ▪ The first annual meeting of Task-Force-Limax, Bünder Naturmuseum, Chur, Switzerland, 8-10 September, 2006: presentation, outcomes and abstracts Isabel HYMAN ▪ Collecting and transporting living slugs (Pulmonata: Limacidae) Isabel HYMAN ▪ A List of type specimens of land and freshwater molluscs from France present in the national molluscs collection of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem Henk K. -

List of Marine Alien and Invasive Species

Table 1: The list of 96 marine alien and invasive species recorded along the coastline of South Africa. Phylum Class Taxon Status Common name Natural Range ANNELIDA Polychaeta Alitta succinea Invasive pile worm or clam worm Atlantic coast ANNELIDA Polychaeta Boccardia proboscidea Invasive Shell worm Northern Pacific ANNELIDA Polychaeta Dodecaceria fewkesi Alien Black coral worm Pacific Northern America ANNELIDA Polychaeta Ficopomatus enigmaticus Invasive Estuarine tubeworm Australia ANNELIDA Polychaeta Janua pagenstecheri Alien N/A Europe ANNELIDA Polychaeta Neodexiospira brasiliensis Invasive A tubeworm West Indies, Brazil ANNELIDA Polychaeta Polydora websteri Alien oyster mudworm N/A ANNELIDA Polychaeta Polydora hoplura Invasive Mud worm Europe, Mediterranean ANNELIDA Polychaeta Simplaria pseudomilitaris Alien N/A Europe BRACHIOPODA Lingulata Discinisca tenuis Invasive Disc lamp shell Namibian Coast BRYOZOA Gymnolaemata Virididentula dentata Invasive Blue dentate moss animal Indo-Pacific BRYOZOA Gymnolaemata Bugulina flabellata Invasive N/A N/A BRYOZOA Gymnolaemata Bugula neritina Invasive Purple dentate mos animal N/A BRYOZOA Gymnolaemata Conopeum seurati Invasive N/A Europe BRYOZOA Gymnolaemata Cryptosula pallasiana Invasive N/A Europe BRYOZOA Gymnolaemata Watersipora subtorquata Invasive Red-rust bryozoan Caribbean CHLOROPHYTA Ulvophyceae Cladophora prolifera Invasive N/A N/A CHLOROPHYTA Ulvophyceae Codium fragile Invasive green sea fingers Korea CHORDATA Actinopterygii Cyprinus carpio Invasive Common carp Asia CHORDATA Ascidiacea -

Thyasira Succisa, Lyonsia Norwegica and Poromya Granulata in The

Marine Biodiversity Records, page 1 of 4. # Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 2015 doi:10.1017/S1755267215000287; Vol. 8; e47; 2015 Published online First record of three Bivalvia species: Thyasira succisa, Lyonsia norwegica and Poromya granulata in the Adriatic Sea (Central Mediterranean) pierluigi strafella, luca montagnini, elisa punzo, angela santelli, clara cuicchi, vera salvalaggio and gianna fabi Istituto di Scienze Marine (ISMAR), Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche (CNR), Largo Fiera della Pesca, 2, 60125 Ancona, Italy Three species of bivalves, Thyasira succisa, Lyonsia norwegica and Poromya granulate, were recorded for the first time in the Adriatic Sea during surveys conducted from 2010 to 2012 on offshore relict sand bottoms at a depth range of 45–80 m. Keywords: Thyasira succisa, Lyonsia norwegica, Poromia granulata, Adriatic Sea, bivalvia Submitted 12 December 2014; accepted 8 March 2015 INTRODUCTION yet been formerly reported in the official checklist for the Italian marine faunal species for the Adriatic Sea Although species distribution changes over time, sudden (Schiaparelli, 2008). range extensions are often prompted by anthropic and The family Thyasiridea (Dall, 1900) includes 14 genera. natural causes. This may be direct, by the introduction of a The species belonging to this family have a small, mostly new species for a defined purpose (e.g. aquaculture) or indir- thin, light shell, with more or less marked plicae on the pos- ect (e.g. ballast water). Natural changes (e.g. global warming) terior end. The anterior margin is often flattened and the could also provide opportunities for species to colonize areas hinge is almost without teeth (Jeffreys, 1876; Pope & Goto, where, until recently, they were not able to survive (Kolar & 1991). -

Minutes of Discussions

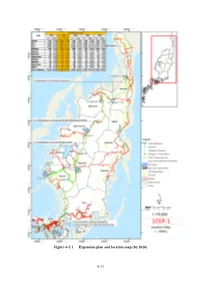

Figure 6-5.1 Expansion plan and location map (by 2020) 6-31 NGARCHELONG STATE アルコロン州 (Ollei) (Ngebei) 2.1km (Oketol) (Ngerbau) 0.9km 1.8km (Ngrill) 1.0km NGARAARD STATE ガラルド州 (Chol School) 1.0km (Urrung) 3.6km (Chelab) NGAREMLENGUI STATE NGARDMAU STATE (Ngerderemang) ガラスマオ州 1.0km アルモノグイ州 3φTr 6MW 750kVA x 1 34.5/13.8kV NGARAARD-2 S/S NGARAARD-1 S/S (Ngkeklau) 3.6km 1φTr 3x25kVA 34.5/13.8kV Busstop(Junction)-Ngardmau: 24.4km Ngardmau-Ngaraard-2: 11.8km ASAHI S/S (Ngermetengel) NGARDMAU NGIWAL STATE S/S 2.9km オギワ-ル州 3φTr 1x300kVA 34.5/13.8kV (Ogill) 1φTr 3x75kVA 34.5/13.8kV NGATPANG STATEガスパン州 IBOBANG S/S (Ngetpang Elementary School) (Ibobang) 2.0km (Ngerutoi) (Dock) (Ngetbong Ice Box) 1φTr 3x75kVA 34.5/13.8kV MELEKEOK STATE メレケオク州 AIMELIIK STATE 8.25km アイメリ-ク州 Busstop NEKKENG S/S (Junction) KOKUSAI S/S 8.8km (Ngeruling) (Oisca) 1φTr 3x75kVA 4MW 34.5/13.8kV AIMELIIK-2 S/S 3φTr 1x5MVA 6.5km 1.2km AIMELIIK-1 S/S 34.5/13.8kV (Community Center) 1φTr 3x75kVA NGCHESAR STATE 1.5km 34.5/13.8kV Busstop(Junction) – チェサ-ル州 3φTr Airai 9.0Km 1x1000kVA 34.5/13.8kV (Rai) (ELECHUI) (AIMELIIK) AIRAI S/S AIMELIIK POWER STATION アイメリ-ク発電所 N10 AIRAI STATE No.1 Tr No.2 Tr 10MVA 10MVA アイライ州 34.5/13.8kV 34.5/13.8kV 3φTr 10MVA 34.5/13.8kV (Airai State) N10 G G 6MW M6 M7 (Airport) 5MW 5MW (Mitsubishi) 15km 13.98km BABELDAOB ISLAND バベルダオブ島 K-B Bridge KOROR ISLAND コロ-ル島 Koror S/S LEGEND 凡例 3φTr PV System 10MVA 太陽光発電設備 34.5/13.8kV GENERATOR G 発電機 Malakal – Airai 9.2Km TRANSFORMER 変圧器 DISCONNECTING SWITCH 断路器 (Hechang) (Koror) LOAD BREAKER SWITCH 負荷開閉器 CIRCUIT BREAKER -

First Observation and Range Extension of the Nudibranch Tenellia Catachroma (Burn, 1963) in Western Australia (Mollusca: Gastropoda)

CSIRO Publishing The Royal Society of Victoria, 129, 37–40, 2017 www.publish.csiro.au/journals/rs 10.1071/RS17003 A VICTORIAN EMIGRANT: FIRST OBSERVATION AND RANGE EXTENSION OF THE NUDIBRANCH TENELLIA CATACHROMA (BURN, 1963) IN WESTERN AUSTRALIA (MOLLUSCA: GASTROPODA) Matt J. NiMbs National Marine Science Centre, Southern Cross University, PO Box 4321, Coffs Harbour, NSW 2450, Australia Correspondence: [email protected] ABSTRACT: The southwest coast of Western Australia is heavily influenced by the south-flowing Leeuwin Current. In summer, the current shifts and the north-flowing Capes Current delivers water from the south to nearshore environments and with it a supply of larvae from cooler waters. The nudibranch Tenellia catachroma (Burn, 1963) was considered restricted to Victorian waters; however, its discovery in eastern South Australia in 2013 revealed its capacity to expand its range west. In March 2017 a single individual was observed in shallow subtidal waters at Cape Peron, Western Australia, some 2000 km to the west of its previous range limit. Moreover, its distribution has extended northwards, possibly aided by the Capes Current, into a location of warming. This observation significantly increases the range for this Victorian emigrant to encompass most of the southern Australian coast, and also represents an equatorward shift at a time when the reverse is expected. Keywords: climate change, Cape Peron, range extension, Leeuwin Current, Capes Current The fionid nudibranch Tenellia catachroma (Burn, 1963) first found in southern NSW in 1979 (Rudman 1998), has was first described from two specimens found at Point been observed only a handful of times since and was also Danger, near Torquay, Victoria, in 1961 (Burn 1963). -

THE LISTING of PHILIPPINE MARINE MOLLUSKS Guido T

August 2017 Guido T. Poppe A LISTING OF PHILIPPINE MARINE MOLLUSKS - V1.00 THE LISTING OF PHILIPPINE MARINE MOLLUSKS Guido T. Poppe INTRODUCTION The publication of Philippine Marine Mollusks, Volumes 1 to 4 has been a revelation to the conchological community. Apart from being the delight of collectors, the PMM started a new way of layout and publishing - followed today by many authors. Internet technology has allowed more than 50 experts worldwide to work on the collection that forms the base of the 4 PMM books. This expertise, together with modern means of identification has allowed a quality in determinations which is unique in books covering a geographical area. Our Volume 1 was published only 9 years ago: in 2008. Since that time “a lot” has changed. Finally, after almost two decades, the digital world has been embraced by the scientific community, and a new generation of young scientists appeared, well acquainted with text processors, internet communication and digital photographic skills. Museums all over the planet start putting the holotypes online – a still ongoing process – which saves taxonomists from huge confusion and “guessing” about how animals look like. Initiatives as Biodiversity Heritage Library made accessible huge libraries to many thousands of biologists who, without that, were not able to publish properly. The process of all these technological revolutions is ongoing and improves taxonomy and nomenclature in a way which is unprecedented. All this caused an acceleration in the nomenclatural field: both in quantity and in quality of expertise and fieldwork. The above changes are not without huge problematics. Many studies are carried out on the wide diversity of these problems and even books are written on the subject.