Aspects: an Investigation Into Life Writing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Futurist Moment : Avant-Garde, Avant Guerre, and the Language of Rupture

MARJORIE PERLOFF Avant-Garde, Avant Guerre, and the Language of Rupture THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS CHICAGO AND LONDON FUTURIST Marjorie Perloff is professor of English and comparative literature at Stanford University. She is the author of many articles and books, including The Dance of the Intellect: Studies in the Poetry of the Pound Tradition and The Poetics of Indeterminacy: Rimbaud to Cage. Published with the assistance of the J. Paul Getty Trust Permission to quote from the following sources is gratefully acknowledged: Ezra Pound, Personae. Copyright 1926 by Ezra Pound. Used by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. Ezra Pound, Collected Early Poems. Copyright 1976 by the Trustees of the Ezra Pound Literary Property Trust. All rights reserved. Used by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. Ezra Pound, The Cantos of Ezra Pound. Copyright 1934, 1948, 1956 by Ezra Pound. Used by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. Blaise Cendrars, Selected Writings. Copyright 1962, 1966 by Walter Albert. Used by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 1986 by The University of Chicago All rights reserved. Published 1986 Printed in the United States of America 95 94 93 92 91 90 89 88 87 86 54321 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Perloff, Marjorie. The futurist moment. Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. Futurism. 2. Arts, Modern—20th century. I. Title. NX600.F8P46 1986 700'. 94 86-3147 ISBN 0-226-65731-0 For DAVID ANTIN CONTENTS List of Illustrations ix Abbreviations xiii Preface xvii 1. -

Mercury's Low-Reflectance Material: Constraints from Hollows

Mercury’s low-reflectance material: Constraints from hollows Rebecca Thomas, Brian Hynek, David Rothery, Susan Conway To cite this version: Rebecca Thomas, Brian Hynek, David Rothery, Susan Conway. Mercury’s low-reflectance material: Constraints from hollows. Icarus, Elsevier, 2016, 277, pp.455-465. 10.1016/j.icarus.2016.05.036. hal-02271739 HAL Id: hal-02271739 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02271739 Submitted on 27 Aug 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Accepted Manuscript Mercury’s Low-Reflectance Material: Constraints from Hollows Rebecca J. Thomas , Brian M. Hynek , David A. Rothery , Susan J. Conway PII: S0019-1035(16)30246-9 DOI: 10.1016/j.icarus.2016.05.036 Reference: YICAR 12084 To appear in: Icarus Received date: 23 February 2016 Revised date: 9 May 2016 Accepted date: 24 May 2016 Please cite this article as: Rebecca J. Thomas , Brian M. Hynek , David A. Rothery , Susan J. Conway , Mercury’s Low-Reflectance Material: Constraints from Hollows, Icarus (2016), doi: 10.1016/j.icarus.2016.05.036 This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. -

The Ecology of Puha: Identity, Orientation, and Shifting Perceptions Reflected Through Material Culture and Socioreligious Practice

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2021 THE ECOLOGY OF PUHA: IDENTITY, ORIENTATION, AND SHIFTING PERCEPTIONS REFLECTED THROUGH MATERIAL CULTURE AND SOCIORELIGIOUS PRACTICE Aaron Robert Atencio Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Atencio, Aaron Robert, "THE ECOLOGY OF PUHA: IDENTITY, ORIENTATION, AND SHIFTING PERCEPTIONS REFLECTED THROUGH MATERIAL CULTURE AND SOCIORELIGIOUS PRACTICE" (2021). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 11734. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/11734 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ECOLOGY OF PUHA: IDENTITY, ORIENTATION, AND SHIFTING PERCEPTIONS REFLECTED THROUGH MATERIAL CULTURE AND SOCIORELIGIOUS PRACTICE By AARON ROBERT ATENCIO Anthropology, University of Montana, Missoula, Montana, U.S.A., 2021 Dissertation Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of PhD Philosophy of Anthropology The University of Montana Missoula, MT Official Graduation Date (May 2021) Approved by: Scott Whittenburg, Dean of The Graduate School Graduate -

FINAL Illinois B + Berkeley B.Pdf

ACF Fall 2014: Nemo auditur propriam derpitudinem allegans Packet by University of Illinois, Urbana Champaign B (Chinmay Kansara and Alex Pandya) and UC Berkeley B (John Gleb, Aseem Keyal, Michael Ling, James Wang) Edited by Jordan Brownstein, Jacob Reed, Max Schindler, Richard Yu, and Ben Zhang Head-editing by Gautam Kandlikar and Gaurav Kandlikar Tossups 1. This location was where a statement claiming that a man was "30% right and 70% wrong" was displayed. In this place, “dare-to-die brigades” were formed by members of the Workers’ Autonomous Federation. Events in this place prompted a call to turn "grief into strength" in the April 26th Editorial. The Seven Demands were issued in this place, where a 33-foot foam statue of a goddess was erected. A march at the funeral of Hu Yaobang ended in this place. Jeff Widener photographed a man in this place carrying two shopping bags and standing in front of a column of tanks. For 10 points, name this place where students protested Deng Xiaoping's government in 1989, a large open space in Beijing. ANSWER: Tiananmen Square [prompt on “Beijing” or “Peking”] 2. This tissue names a type of fin found on some fish between the dorsal and caudal fins. Some types of this tissue contain mitochondria with a unique uncoupling protein that initiates an oxidative phosphorylation reaction to produce heat instead of ATP. Yellow bone marrow consists mainly of cells from this tissue. Ob/ob [“o-b o-b”] mice contain greater amounts of this tissue because of their inability to secrete leptin, which these cells produce to suppress hunger. -

Back Matter (PDF)

Index Page numbers in italic denote Figures. Page numbers in bold denote Tables. ‘a’a lava 15, 82, 86 Belgica Rupes 272, 275 Ahsabkab Vallis 80, 81, 82, 83 Beta Regio, Bouguer gravity anomaly Aino Planitia 11, 14, 78, 79, 83 332, 333 Akna Montes 12, 14 Bhumidevi Corona 78, 83–87 Alba Mons 31, 111 Birt crater 378, 381 Alba Patera, flank terraces 185, 197 Blossom Rupes fold-and-thrust belt 4, 274 Albalonga Catena 435, 436–437 age dating 294–309 amors 423 crater counting 296, 297–300, 301, 302 ‘Ancient Thebit’ 377, 378, 388–389 lobate scarps 291, 292, 294–295 anemone 98, 99, 100, 101 strike-slip kinematics 275–277, 278, 284 Angkor Vallis 4,5,6 Bouguer gravity anomaly, Venus 331–332, Annefrank asteroid 427, 428, 433 333, 335 anorthosite, lunar 19–20, 129 Bransfield Rift 339 Antarctic plate 111, 117 Bransfield Strait 173, 174, 175 Aphrodite Terra simple shear zone 174, 178 Bouguer gravity anomaly 332, 333, 335 Bransfield Trough 174, 175–176 shear zones 335–336 Breksta Linea 87, 88, 89, 90 Apollinaris Mons 26,30 Brumalia Tholus 434–437 apollos 423 Arabia, mantle plumes 337, 338, 339–340, 342 calderas Arabia Terra 30 elastic reservoir models 260 arachnoids, Venus 13, 15 strike-slip tectonics 173 Aramaiti Corona 78, 79–83 Deception Island 176, 178–182 Arsia Mons 111, 118, 228 Mars 28,33 Artemis Corona 10, 11 Caloris basin 4,5,6,7,9,59 Ascraeus Mons 111, 118, 119, 205 rough ejecta 5, 59, 60,62 age determination 206 canali, Venus 82 annular graben 198, 199, 205–206, 207 Canary Islands flank terraces 185, 187, 189, 190, 197, 198, 205 lithospheric flexure -

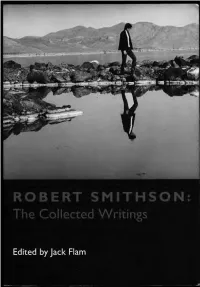

Collected Writings

THE DOCUMENTS O F TWENTIETH CENTURY ART General Editor, Jack Flam Founding Editor, Robert Motherwell Other titl es in the series available from University of California Press: Flight Out of Tillie: A Dada Diary by Hugo Ball John Elderfield Art as Art: The Selected Writings of Ad Reinhardt Barbara Rose Memo irs of a Dada Dnnnmer by Richard Huelsenbeck Hans J. Kl ein sc hmidt German Expressionism: Dowments jro111 the End of th e Wilhelmine Empire to th e Rise of National Socialis111 Rose-Carol Washton Long Matisse on Art, Revised Edition Jack Flam Pop Art: A Critical History Steven Henry Madoff Co llected Writings of Robert Mothen/le/1 Stephanie Terenzio Conversations with Cezanne Michael Doran ROBERT SMITHSON: THE COLLECTED WRITINGS EDITED BY JACK FLAM UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS Berkeley Los Angeles Londo n University of Cali fornia Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. London, England © 1996 by the Estate of Robert Smithson Introduction © 1996 by Jack Flam Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Smithson, Robert. Robert Smithson, the collected writings I edited, with an Introduction by Jack Flam. p. em.- (The documents of twentieth century art) Originally published: The writings of Robert Smithson. New York: New York University Press, 1979. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-520-20385-2 (pbk.: alk. paper) r. Art. I. Title. II. Series. N7445.2.S62A3 5 1996 700-dc20 95-34773 C IP Printed in the United States of Am erica o8 07 o6 9 8 7 6 T he paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of ANSII NISO Z39·48-1992 (R 1997) (Per111anmce of Paper) . -

Blackfoot Confederacy Keepers of the Rocky Mountains by Tarissa L

Blackfoot Confederacy Keepers of the Rocky Mountains Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Spoonhunter, Tarissa L. Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 26/09/2021 07:16:58 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/323418 Blackfoot Confederacy Keepers of the Rocky Mountains by Tarissa L. Spoonhunter __________________________ Copyright © Tarissa Spoonhunter 2014 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the GRADUATE INTERDISCIPLINARY PROGRAM IN AMERICAN INDIAN STUDIES In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2014 Blackfoot Confederacy Keepers of the Rocky Mountains Spoonhunter2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Tarissa Spoonhunter, titled Blackfoot Confederacy Keepers of the Rocky Mountains and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Benedict Colombi Date: May 5, 2014 Eileen Luna-Firebaugh Date: May 5, 2014 Manley Begay Date: May 5, 2015 Final approval and acceptance of this dissertation is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the dissertation to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this dissertation prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement. -

Issn 0976-299X Vol. X Special Issue No. 1 January 2019

www.literaryendeavour.org ISSN 0976-299X LITERARY ENDEAVOUR UGC Approved Quarterly International Refereed Journal of English Language, Literature and Criticism UGC Approved Under Arts and Humanities Journal No. 44728 VOL. X SPECIAL ISSUE NO. 1 JANUARY 2019 Chief Editor Dr. Ramesh Chougule Registered with the Registrar of Newspaper of India vide MAHENG/2010/35012 ISSN 0976-299X ISSN 0976-299X www.literaryendeavour.org LITERARY ENDEAVOUR UGC Approved Under Arts and Humanities Journal No. 44728 INDEXED IN GOOGLE SCHOLAR EBSCO PUBLISHING Owned, Printed and published by Sou. Bhagyashri Ramesh Chougule, At. Laxmi Niwas, House No. 26/1388, Behind N. P. School No. 18, Bhanunagar, Osmanabad, Maharashtra – 413501, India. LITERARY ENDEAVOUR ISSN 0976-299X A Quarterly International Refereed Journal of English Language, Literature and Criticism UGC Approved Under Arts and Humanities Journal No. 44728 VOL. X : SPECIAL ISSUE NO. 1 : JANUARY, 2019 Editorial Board Editorial... Editor-in-Chief Writing in English literature is a global phenomenon. It represents Dr. Ramesh Chougule ideologies and cultures of the particular region. Different forms of literature Associate Professor & Head, Department of English, like drama, poetry, novel, non-fiction, short story etc. are used to express Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Marathwada University, Sub-Campus, Osmanabad, Maharashtra, India one's impressions and experiences about the socio-politico-religio-cultural Co-Editor and economic happenings of the regions. The World War II brings vital Dr. S. Valliammai changes in the outlook of authors in the world. Nietzsche's declaration of Department of English, death of God and the appearance of writers like Edward Said, Michele Alagappa University, Karaikudi, TN, India Foucault, Homi Bhabha, and Derrida bring changes in the exact function of Members literature in moulding the human life. -

Behold an Animal: Four Exorbitant Readings

UC Irvine FlashPoints Title Behold an Animal: Four Exorbitant Readings Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0c7881t5 ISBN 978-0-8101-4071-4 Author Ravindranathan, Thangam Publication Date 2020-02-10 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Behold an Animal The FlashPoints series is devoted to books that consider literature beyond strictly national and disciplinary frameworks and that are distinguished both by their historical grounding and by their theoretical and conceptual strength. Our books engage theory without losing touch with history and work historically without falling into uncritical positivism. FlashPoints aims for a broad audience within the humanities and the social sciences concerned with moments of cultural emergence and transformation. In a Benjaminian mode, FlashPoints is interested in how liter- ature contributes to forming new constellations of culture and history and in how such formations function critically and politically in the present. Series titles are available online at http://escholarship.org/uc/fl ashpoints. series editors: Ali Behdad (Comparative Literature and English, UCLA), Edi- tor Emeritus; Judith Butler (Rhetoric and Comparative Literature, UC Berkeley), Editor Emerita; Michelle Clayton (Hispanic Studies and Comparative Literature, Brown University); Edward Dimendberg (Film and Media Studies, Visual Studies, and European Languages and Studies, UC Irvine), Founding Editor; Catherine Gallagher (English, UC Berkeley), Editor Emerita; Nouri Gana (Comparative Lit- erature and Near Eastern Languages and Cultures, UCLA); Susan Gillman (Lit- erature, UC Santa Cruz), Coordinator; Jody Greene (Literature, UC Santa Cruz); Richard Terdiman (Literature, UC Santa Cruz), Founding Editor A complete list of titles begins on p. 254. Behold an Animal Four Exorbitant Readings Thangam Ravindranathan northwestern university press | evanston, illinois Northwestern University Press www.nupress.northwestern.edu Copyright © 2020 by Northwestern University Press. -

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-15445-2 — Mercury Edited by Sean C

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-15445-2 — Mercury Edited by Sean C. Solomon , Larry R. Nittler , Brian J. Anderson Index More Information INDEX 253 Mathilde, 196 BepiColombo, 46, 109, 134, 136, 138, 279, 314, 315, 366, 403, 463, 2P/Encke, 392 487, 488, 535, 544, 546, 547, 548–562, 563, 564, 565 4 Vesta, 195, 196, 350 BELA. See BepiColombo: BepiColombo Laser Altimeter 433 Eros, 195, 196, 339 BepiColombo Laser Altimeter, 554, 557, 558 gravity assists, 555 activation energy, 409, 412 gyroscope, 556 adiabat, 38 HGA. See BepiColombo: high-gain antenna adiabatic decompression melting, 38, 60, 168, 186 high-gain antenna, 556, 560 adiabatic gradient, 96 ISA. See BepiColombo: Italian Spring Accelerometer admittance, 64, 65, 74, 271 Italian Spring Accelerometer, 549, 554, 557, 558 aerodynamic fractionation, 507, 509 Magnetospheric Orbiter Sunshield and Interface, 552, 553, 555, 560 Airy isostasy, 64 MDM. See BepiColombo: Mercury Dust Monitor Al. See aluminum Mercury Dust Monitor, 554, 560–561 Al exosphere. See aluminum exosphere Mercury flybys, 555 albedo, 192, 198 Mercury Gamma-ray and Neutron Spectrometer, 554, 558 compared with other bodies, 196 Mercury Imaging X-ray Spectrometer, 558 Alfvén Mach number, 430, 433, 442, 463 Mercury Magnetospheric Orbiter, 552, 553, 554, 555, 556, 557, aluminum, 36, 38, 147, 177, 178–184, 185, 186, 209, 559–561 210 Mercury Orbiter Radio Science Experiment, 554, 556–558 aluminum exosphere, 371, 399–400, 403, 423–424 Mercury Planetary Orbiter, 366, 549, 550, 551, 552, 553, 554, 555, ground-based observations, 423 556–559, 560, 562 andesite, 179, 182, 183 Mercury Plasma Particle Experiment, 554, 561 Andrade creep function, 100 Mercury Sodium Atmospheric Spectral Imager, 554, 561 Andrade rheological model, 100 Mercury Thermal Infrared Spectrometer, 366, 554, 557–558 anorthosite, 30, 210 Mercury Transfer Module, 552, 553, 555, 561–562 anticline, 70, 251 MERTIS. -

The George-Anne Student Media

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern The George-Anne Student Media 4-2-2009 The George-Anne Georgia Southern University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/george-anne Part of the Higher Education Commons Recommended Citation Georgia Southern University, "The George-Anne" (2009). The George-Anne. 3158. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/george-anne/3158 This newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Media at Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in The George-Anne by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ■■I^^^BMI Serving Georgia Southern University and the Statesboro Community Since 1927 • Questions? Call 912-478-5246. f 1 ^ ^ www.GADaily.com LrEORGE- THURSDAY, APRIL 2,2009 • VOLUME 82. • ISSUE 1 COVERING THE CAMPUS LIKE A SWARM OF GNATS Special Photo NEWS > ' Three-Day Forecast . Web Exclusive: 'Battle for the Boro' gears up for Today Saturday the weekend at Dos Primos and I Friday T-storms "•**%*"<*' T-storms Living with Celiac Disease Shenanigans. See if your favorite T-storms 70/61 0 77/47 79/52 Only at www.GADaily.com Vband is on the list. PAGE 13; V*fc jm PAGE 2 I ADVERTISEMENT THE GEORGE-ANNE I THURSDAY, APRIL 2,2009 VQtl /OHwireless 1 ^■BI^L Unlimited calling to any 10 numbers. Anywhere in America. Anytime, /lumbers to share on any Nationwide Family SharePlan® with 1400 Anytime Minutes or more. ers on any Nationwide Single-Line Plan with 900 Anytime Minutes or more. -

Recovering the Feminine Voice in Nabokov's Lolita

Belmont University Belmont Digital Repository English Theses School of Humanities Winter 11-20-2020 This Is What Makes Us Girls: Recovering the Feminine Voice in Nabokov's Lolita Amanda Wulforst [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.belmont.edu/english_theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Wulforst, Amanda, "This Is What Makes Us Girls: Recovering the Feminine Voice in Nabokov's Lolita" (2020). English Theses. 1. https://repository.belmont.edu/english_theses/1 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Humanities at Belmont Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Theses by an authorized administrator of Belmont Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 2 Table of Contents Chapter 1: Such a Nasty Woman: Reclaiming Lolita from Toxic Freudian Analysis and Cultural Misconceptions ..................................................................................................... 5 1.1 Literary criticism ....................................................................................................... 6 1.2 Lolita’s modern significance ..................................................................................... 9 Chapter 2: (You’re the) Devil in Disguise: Exposing Lolita’s Abuser and Contemplating His Madness ...................................................................................................................... 23 2.1 The man behind