25 Gavin Cerini.Pdf 773.57 Kb

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Gunditjmara Land Justice Story Jessica K Weir

The legal outcomes the Gunditjmara achieved in the 1980s are often overlooked in the history of land rights and native title in Australia. The High Court Onus v Alcoa case and the subsequent settlement negotiated with the State of Victoria, sit alongside other well known bench marks in our land rights history, including the Gurindji strike (also known as the Wave Hill Walk-Off) and land claim that led to the development of land rights legislation in the Northern Territory. This publication links the experiences in the 1980s with the Gunditjmara’s present day recognition of native title, and considers the possibilities and limitations of native title within the broader context of land justice. The Gunditjmara Land Justice Story JESSICA K WEIR Euphemia Day, Johnny Lovett and Amy Williams filming at Cape Jessica Weir together at the native title Bridgewater consent determination Amy Williams is an aspiring young Jessica Weir is a human geographer Indigenous film maker and the focused on ecological and social communications officer for the issues in Australia, particularly water, NTRU. Amy has recently graduated country and ecological life. Jessica with her Advanced Diploma of completed this project as part of her Media Production, and is developing Research Fellowship in the Native Title and maintaining communication Research Unit (NTRU) at the Australian strategies for the NTRU. Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies. The Gunditjmara Land Justice Story JESSICA K WEIR First published in 2009 by the Native Title Research Unit, the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies GPO Box 553 Canberra ACT 2601 Tel: (61 2) 6246 1111 Fax: (61 2) 6249 7714 Email: [email protected] Web: www.aiatsis.gov.au/ Written by Jessica K Weir Copyright © Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies. -

Seventh Report of the Board for the Protection

APPENDIX V. DISTRIBUTION of Stores for the use of the Aborigines by the Central Board from the 1st August 1868 to 31st July 1869. Name of Station. Miscellaneous. Coranderrk 700 ft. lumber, 9 bushels lime, 2 quarts ipec. wine, 1/2-lb. tr. opium, 2 lbs. senna, 1 quart spirits turpentine, 1 lb. camphor, 2 lbs. soft soap, 8 lbs. rhubarb. 8 ozs. jalap, 1 oz. quinine, 1 pint ammonia, 12 doz. copy-books, 96 lesson books, 24 penholders, 3 boxes nibs, 1 quart ink, 12 dictionaries, 24 slates, 1 ream foolscap, 24 arithmetic books, 3 planes, 4 augers, 1 rule, 12 chisels, 3 gouges, 3 mortising chisels, 1 saw, 1 brace and bits, 2 pruning knives, 50 lbs. sago, 1000 lbs. salt, 10 lbs. hops, 36 boys' twill shirts, 150 yds. calico, 200 yds. prints, 60 yds. twill, 100 yds. osnaberg, 150 yds. holland, 100 yds, flannel, 150 yds. plaid, 100 yds. winsey, 36 doz. hooks and eyes, 2 doz. pieces tape, 2 pkgs. piping cord, 4 lbs. thread, 48 reels cotton, 200 needles, 4 lbs. candlewick, 24 tooth combs, 24 combs, 6 looking-glasses, 6 candlesticks, 6 buckets, 36 pannikins, 6 chambers, 2 pairs scissors, 24 spoons, 1 soup ladle, 36 knives and forks, 2 teapots, 2 slop pails, 6 scrubbing brushes, 2 whitewash brushes, 12 bath bricks, 2 enamelled dishes, 12 milk pans, 12 wash-hand basins, 6 washing tubs, 12 crosscut-saw files, 12 hand-saw files, 2 crosscut saws, 12 spades, 12 hoes, 12 rakes, 12 bullock bows and keys, 100 lbs. nails, 1 plough, 1 set harrows, 1 saddle and bridle, 2 sets plough harness, 6 rings for bullock yokes, 1 harness cask. -

Twenty Fifth Report of the Central Board for the Protection of The

1889. VICTORIA. TWENTY-FIFTH REPORT OF THE BOARD TOR THE PROTECTION OF THE ABORIGINES IN THE COLONY OF VICTORIA. PRESENTED TO BOTH HOUSES OF PARLIAMENT BY HIS EXCELLENCY'S COMMAND By Authority: ROBT. S. BRAIN, GOVERNMENT PRINTER, MELBOURNE. No. 129.—[!•.]—17377. Digitised by AIATSIS Library, SF 25.3/1 - www.aiatsis.gov.au APPROXIMATE COST OF REPORT. Preparation— Not given, £ s. d. Printing (760 copies) ., .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 25 0 0 Digitised by AIATSIS Library, SF 25.3/1 - www.aiatsis.gov.au REPORT. 4th November, 1889. SIR, The Board for the Protection of the Aborigines have the honour to submit for Your Excellency's consideration their Twenty-fifth Report on the condition of the Aborigines of this colony, together with the reports from the managers of the stations, and other papers. 1. The Board have held two special and eight ordinary meetings during the past year. 2. The average numbers of Aborigines and half-castes who have resided on the various stations during the year are as follow:— Coranderrk, under the management of Mr. Shaw 78 Framlingham, „ „ Mr. Goodall 90 Lake Condah, „ „ Revd. J. H. Stable 84 Lake Wellington, „ „ Revd. F. A. Hagenauer 61 Lake Tyers, „ „ Revd. John Bulmer 60 Lake Hindmarsh, „ „ Revd. P. Bogisch 48 421 Others visit the stations and reside there during short periods of the year. 3. The number of half-castes, who, under the operation of the new Act for the merging of half-castes among the general population of the colony, are earning their living with some assistance from the Board is 113. 4. Rations and clothing are still supplied to those of the half-castes who, according to the " Amended Act," satisfy the Board of their necessitous circum stances. -

The Gunditjmara People in Having This Place Recognised As a Place of the Spirit, a Place of Human Technology and Ingenuity and As a Place of Resistance

Budj Bim Caring for the spirit and the people Damein Bell Manager - Lake Condah Sustainable Development Project 21 Scott Street Heywood 3304 Australia [email protected] Ms Chris Johnston Context Pty Ltd 22 Merri Street Brunswick 3056 Australia [email protected] Abstract: Budj Bim National Heritage Landscape represents the extraordinary triumph of the Gunditjmara people in having this place recognised as a place of the spirit, a place of human technology and ingenuity and as a place of resistance. The Gunditjmara are the Indigenous people of this part of south- western Victoria, Australia. In this landscape, more than 30 000 years ago the Gunditjmara witnessed an important creation being, reveal himself in the landscape. Budj Bim (known today as Mount Eccles) is the source of an immense lava flow which transformed the landscape. The Gunditjmara people developed this landscape by digging channels, creating ponds and wetlands and shaping an extensive aquaculture system, providing an economic basis for the development of a settled society. This paper will present the complex management planning that has gone into restoring the lake and re-establishing Gunditjmara management, reversing the tide of Australian history, and enabling the spirit of this sacred place to again be cared for. Introduction The ancestral creation-being is revealed in the landscape of south-western Victoria (Australia) at Budj Bim (Mt Eccles). At Mount Eccles the top of his head is revealed, his teeth tung att are the scoria cones. His spirit is embedded deep in this place and in the people – Gunditjmara. Listing of Budj Bim National Heritage Landscape on Australian’s new national heritage list in 2004 was an extraordinary achievement for a remarkable people. -

Summary of HFNC Presidents' AGM Reports and Minutes 1958-2008

Summary of HFNC Presidents’ AGM Reports and Minutes 1958-2008 The following dot-point summaries of the Presidents‟ Reports for the Annual General Meetings (AGM) and HFNC Minutes provide a comprehensive overview of major activities undertaken and issues addressed each year. They also show the continuing projects and concerns that were current in particular years. 1959 May – President Mr Dewar Goode – report for 1958-59 Mr Goode presented the first annual report, expressing the philosophy of the HFNC: Informal friendly cooperation within the Club, with each contributing to the pool of knowledge. The need to have established National Parks within the region – the Grampians and the Glenelg River – indeed to establish a series of National Parks from the coast to the northern arid regions that could be of great importance to science, and to preserve for posterity the remnants of our lovely and fascinating natural features. To monitor and reduce the number, intensity and extent of fires that threaten native plants and animals. That the HFNC should act to ensure that important ecological areas are established under a planned program that will preserve their plant and animal wildlife and special features for the enjoyment of this and future generations. It is better and cheaper to preserve a natural feature than to try and replace it after it has been removed or destroyed. Field Naturalists are the watchdogs of the environment – our cause is indeed worthy. The Secretary/Treasurer, Mr Don Adams, presented his report. he Club has been fortunate to have distinguished speakers – Dr Smith (Director of National Parks), Dr Kneebone (presented a film on Grampian wildflowers), Mr G Thompson (Chairman of the Soil Conservation Authority), Mr B Jennings (Forests Commission of Victoria) and Mr Turner (snakes of the district). -

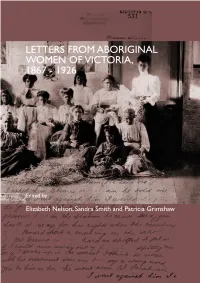

Letters from Aboriginal Women of Victoria, 1867-1926, Edited by Elizabeth Nelson, Sandra Smith and Patricia Grimshaw (2002)

LETTERS FROM ABORIGINAL WOMEN OF VICTORIA, 1867 - 1926 LETTERS FROM ABORIGINAL WOMEN OF VICTORIA, 1867 - 1926 Edited by Elizabeth Nelson, Sandra Smith and Patricia Grimshaw History Department The University of Melbourne 2002 © 2002 Copyright is held on individual letters by the individual contributors or their descendants. No reproduction without permission. All rights reserved. Published in 2002 by The History Department The University of Melbourne Melbourne, Australia The National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry: Letters from aboriginal women in Victoria, 1867-1926. ISBN 0 7340 2160 7. 1. Aborigines, Australian - Women - Victoria - Correspondence. 2. Aborigines, Australian - Women - Victoria - Social conditions. 3. Aborigines, Australian - Government policy - Victoria. 4. Victoria - History. I. Grimshaw, Patricia, 1938- . II. Nelson, Elizabeth, 1972- . III. Smith, Sandra, 1945- . IV. University of Melbourne. Dept. of History. (Series : University of Melbourne history research series ; 11). 305.8991509945 Front cover details: ‘Raffia workers at Coranderrk’ Museum of Victoria Photographic Collection Reproduced courtesy Museum Victoria Layout and cover design by Design Space TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements 7 Map 9 Introduction 11 Notes on Editors 21 The Letters: Children and family 25 Land and housing 123 Asserting personal freedom 145 Regarding missionaries and station managers 193 Religion 229 Sustenance and material assistance 239 Biographical details of the letter writers 315 Endnotes 331 Publications 357 Letters from Aboriginal Women of Victoria, 1867 - 1926 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We have been helped to pursue this project by many people to whom we express gratitude. Patricia Grimshaw acknowledges the University of Melbourne Small ARC Grant for the year 2000 which enabled transcripts of the letters to be made. -

Twelfth Report of the Board for the Protection of the Aborigines in The

1876. VICTORIA. TWELFTH REPORT OF THE BOARD FOR THE PROTECTION OF THE ABORIGINES IN THE COLONY OF VICTORIA. PRESENTED TO BOTH HOUSES OF PARLIAMENT BY HIS EXCELLENCY'S COMMAND. By Authority: GEORGE SKINNER, ACTING GOVERNMENT PRINTER, MELBOURNE, No. 25. Digitised by AIATSIS Library, SF 25.3/1 - www.aiatsis.gov.au/library APPROXIMATE COST OF REPORT. £ s. d. Preparation—Not given. Printing (850 copies) .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 40 10 0 Digitised by AIATSIS Library, SF 25.3/1 - www.aiatsis.gov.au/library REPORT. Melbourne, 30th June 1876. MAY IT PLEASE YOUR EXCELLENCY— The Board for the Protection of the Aborigines has the honor to submit this the Twelfth Annual Report of its progress, with other reports and returns relating to the Aborigines, which are attached as Appendices. The number of natives living on the stations is as follows :— Coranderrk Lake Hindmarsh Lake Condah Lake Wellington Framlingham Lake Tyers There is also a large number of Aborigines still unreclaimed, many of whom are supplied with rations, blankets, and slops, whom it is very desirable to bring under the direct supervision of the Board. The gross value of produce raised on each station is as follows :—Coranderrk, £1,343 2s. 7d.; Lake Wellington, £67 9s. 9d.; Lake Hindmarsh, £195 16s. 10d.; Framlingham (estimated), £150; Lake Condah, £25 6s. 7d.; Lake Tyers, £69 16s. Although the area under hops at Coranderrk was increased this year by four acres, the weight produced was only about the same as last year. It will also be noticed that there is a falling off in the gross cash proceeds, which is accounted for by a fall in the market of about fourpence per lb. -

The Hamilton Region of South-Western Victoria: an Historical Perspective of Landscape, Settlement and Impacts on Aborigine Occupants, Flora and Fauna

The Hamilton region of south-western Victoria: An historical perspective of landscape, settlement and impacts on Aborigine occupants, flora and fauna Rod Bird 2011 1 Cover photo: Aboriginal rock art in Burrunj (Western Black Range), Victoria (Rod Bird 1974). Other photographs are also by the author. This report contains some material prepared for RMIT University student tours to SW Victoria in 1998-2002 and for a Public Forum “Managing our waterways – past, present and future” held by the Glenelg-Hopkins CMA on 30 May 1999. A series of 7 articles on this theme were published in the Hamilton Spectator, from 10 July to 19 Aug 1999. A version of ‘Currewurt spirits in stone’ (Rod Bird, 2009) was set to music by Vaughan McAlley (University of Melbourne), commissioned by the Southern Grampians Promenade of Sacred Music Committee. It was performed in the ‘Promenade Prom’ concert in St Andrew’s Presbyterian Church, Hamilton, on 17 April 2010. The conductor was Douglas Lawrence OAM and the soprano was Deborah Kayser. Publisher: PR Bird 21 Collins St Hamilton, Vic 3300. Author: Rod Bird (Patrick Rodney Bird, PhD, OAM), 1942- The Hamilton region of south-western Victoria: an historical perspective of landscape, settlement and impacts on Aborigine occupants, flora and fauna ISBN: 978-0-9870791-5-2 Disclaimer: Every effort has been made to ensure that the information in this report is accurate but the author and publisher do not guarantee that it is without flaw of any kind and therefore disclaims all liability for any error, loss or other consequence that may arise from you relying on any information in it. -

Condah During World War I What Was the Condah Experience During the 1914-1918 War?

Condah during World War I What was the Condah experience during the 1914-1918 war? Heywood Sub-branch RSL presents… 1 | Page Front cover: A collage of Condah images showing life at home and some of those who enlisted Back cover: Letter from Condah resident Elizabeth Malt to Officer in Charge, Base Record Office, Victoria Barracks, Melbourne in 1918, requesting information about the grave of Pte Ernest Albert Looker, No 6059 and 39th Battalion, her daughter’s fiancé. This booklet has been prepared using a limited number of primary sources. It provides a ‘snapshot’ of some members of the Condah community during the 1914 to 1919 period. A more extensive study using a broader range of sources would be needed for it to have a claim to be representative of the community and time. Maryanne Martin, 2014 Copyright, Maryanne Martin, 2014 ISBN: 978-0-9924883-0-7 2 | Page Dedicated to Susan Jane Routledge, née McLeod In her late twenties Susie fell in love with Howard Routledge the storekeeper at Branxholme. Before they could be married the war broke out and Howard decided to enlist. He refused to marry before leaving, fearful that if he did not return he would leave behind a widow and child. During the war Susie continued her work as a domestic servant on Arrandoovong, wrote letters to Howard, her brother Norman (Scotty) and her four first cousins who had also enlisted (Donny McLeod, Dugald and Duncan McCallum and Hugh McLachlan). It’s probable that she participated in fund raising for the war effort and also corresponded with other men who had enlisted from her community. -

Water for Victoria Discussion Paper

WATER FOR VICTORIA DISCUSSION PAPER Water for Victoria Managing water together Water is fundamental to our communities. We will manage water to support a healthy environment, a prosperous economy and thriving communities, now and into the future. 1 Aboriginal acknowledgement The Victorian Government proudly acknowledges Victoria’s Aboriginal community and their rich culture and pays respect to their Elders past and present. We acknowledge Aboriginal people as Australia’s first peoples and as the Traditional Owners and custodians of the land and water on which we rely. We recognise and value the ongoing contribution of Aboriginal people and communities to Victorian life and how this enriches us. We embrace the spirit of reconciliation, working towards the equality of outcomes and ensuring an equal voice. 2 1 Throughout this document the term ‘Aboriginal’ is used to refer to both Aboriginal and Torres 4 Strait Islander people. Use of the term ‘Indigenous’ is retained in the name and reference to 3 programs, initiatives and publication titles, and unless noted otherwise, is inclusive of both Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. 5 6 8 7 Previous pages images courtesy, 1 North East Catchment Management Authority; 9 2 and 3 Mallee Catchment Management Authority; 4 South East Water; 5 Museums Victoria; 6, 8 and 9 Melbourne Water; 7 Western Water The Premier of Victoria The Minister for Environment, Climate Change and Water Over the past twelve months, we have travelled across Victoria to hear from local communities about water. The message was loud and clear – water is critical – and in the face of climate change, population growth and increasing demand we need a plan. -

'Willing to Fight to a Man': the First World War And

‘Willing to fight to a man’: The First World War and Aboriginal activism in the Western District of Victoria Jessica Horton In April 1916, The Age ran a short story headed ‘Aborigines in camp: Others willing to fight’, announcing the presence of two ‘full-blooded [sic] natives’ among the soldiers at the Ballarat training camp.1 The men’s presence blatantly contradicted popular interpretations of the Defence Act 1909 (Cth).2 Only men of ‘substantial European origin’ were eligible to enlist in the First Australian Imperial Force (AIF), although, in May 1917, the regulations were modified allowing ‘half-caste’ Aboriginal men entry.3 The Aboriginal men volunteering to fight in April 1916 were James Arden and Richard King, Gunditjmara men from the Lake Condah Aboriginal Reserve in the Victorian Western District. In the Condah area there was already an acceptance of Aboriginal men’s participation in sport and labour; during the First World War, this extended to military service.4 The men’s ‘splendid physique’ may have justified their acceptance into the military.5 James Arden was a ‘well known rough rider’ and Richard King had ‘claimed distinction as a footballer and all-round athlete’. The journalist portrayed the spectacle of the Aboriginal men at the Ballarat training camp to 1 The Age, 13 April 1916. PROV VPRS 1694, Unit 3, 1917 correspondence. The newspaper report misspells Arden’s name as Harding. The story also featured in the Horsham Times, the Portland Observer and the St Arnaud Mercury. 2 Defence Act 1903–1909 (Cth). Scarlett 2014: 3. 3 For changes to military regulations see Winegard 2012a: 54. -

Aboriginal Eel Aquaculture in Guditjmara Country by Maria Jose

Eel aquaculture in Gunditjmara Country Aboriginal eel aquaculture system in Gunditjmara Country, South West Victoria, Australia. María José Zúñiga Figure 1 Network of shallow races and ponds for eel harvesting. Eel aquaculture Gunditjmara Country Context. Location: Victoria, Australia Period: 4000 B.C Function: Eel aquaculture Landscape type: Volcano stream Area: 9935 ha. Water type: Fresh water Components: Canals, weirs, races and traps following the trace of a volcano stream. Status: Recreational use UNESCO World Heritage Site for cultural landscape. The Budj Bim Cultural Landscape is located in the Country of the Gunditjmara aboriginal people in Victoria, Australia. Budj Bim (known today as Mount Eccles) is the volcano that thousands of years ago caused an extensive lava flow that transformed the landscape and provided the base for the aquaculture system developed by the Gunditjmara people. The extensive network of canals, traps and weirs was once a highly productive aquaculture system constructed to trap, store and harvest eels. Today, it is recognized as one of the world’s most extensive and oldest aquaculture systems. Watershed Lava flow Figure 4 Regional scale South West Victoria Figure 2 Figure 3 Country scale Provincial scale Australia Victoria Eel aquaculture Gunditjmara Country Remaining traces in the landscape. Large parts of the system have now disappeared, not only because of environmental changes through time, but also because of the modifications done to the site during Brit- ish colonization. Nowadays, it is hard to grasp the entirety of what the system once was. However, several areas have been protected and reconstructed, showing a network of components that blend in with the landscape.