The Growth of “Localism” in Hong Kong

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reviewing and Evaluating the Direct Elections to the Legislative Council and the Transformation of Political Parties in Hong Kong, 1991-2016

Journal of US-China Public Administration, August 2016, Vol. 13, No. 8, 499-517 doi: 10.17265/1548-6591/2016.08.001 D DAVID PUBLISHING Reviewing and Evaluating the Direct Elections to the Legislative Council and the Transformation of Political Parties in Hong Kong, 1991-2016 Chung Fun Steven Hung The Education University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong After direct elections were instituted in Hong Kong, politicization inevitably followed democratization. This paper intends to evaluate how political parties’ politics happened in Hong Kong’s recent history. The research was conducted through historical comparative analysis, with the context of Hong Kong during the sovereignty transition and the interim period of democratization being crucial. For the implementation of “one country, two systems”, political democratization was hindered and distinct political scenarios of Hong Kong’s transformation were made. The democratic forces had no alternative but to seek more radicalized politics, which caused a decisive fragmentation of the local political parties where the establishment camp was inevitable and the democratic blocs were split into many more small groups individually. It is harmful. It is not conducive to unity and for the common interests of the publics. This paper explores and evaluates the political history of Hong Kong and the ways in which the limited democratization hinders the progress of Hong Kong’s transformation. Keywords: election politics, historical comparative, ruling, democratization The democratizing element of the Hong Kong political system was bounded within the Legislative Council under the principle of the separation of powers of the three governing branches, Executive, Legislative, and Judicial. Popular elections for the Hong Kong legislature were introduced and implemented for 25 years (1991-2016) and there were eight terms of general elections for the Legislative Council. -

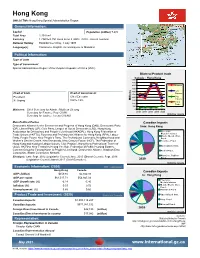

Hong Kong Official Title: Hong Kong Special Administration Region General Information

Hong Kong Official Title: Hong Kong Special Administration Region General Information: Capital Population (million) 7.474n/a Total Area 1,104 km² Currency 1 CAN$=5.791 Hong Kong $ (HKD) (2020 - Annual average) National Holiday Establishment Day, 1 July 1997 Language(s) Cantonese, English, increasing use of Mandarin Political Information: Type of State Type of Government Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China (PRC). Bilateral Product trade Canada - Hong Kong 5000 4500 4000 Balance 3500 3000 Can. Head of State Head of Government Exports 2500 President Chief Executive 2000 Can. Imports XI Jinping Carrie Lam Millions 1500 Total 1000 Trade 500 Ministers: Chief Secretary for Admin.: Matthew Cheung 0 Secretary for Finance: Paul CHAN 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 Statistics Canada Secretary for Justice: Teresa CHENG Main Political Parties Canadian Imports Democratic Alliance for the Betterment and Progress of Hong Kong (DAB), Democratic Party from: Hong Kong (DP), Liberal Party (LP), Civic Party, League of Social Democrats (LSD), Hong Kong Association for Democracy and People’s Livelihood (HKADPL), Hong Kong Federation of Precio us M etals/ stones Trade Unions (HKFTU), Business and Professionals Alliance for Hong Kong (BPA), Labour M ach. M ech. Elec. Party, People Power, New People’s Party, The Professional Commons, Neighbourhood and Prod. Worker’s Service Centre, Neo Democrats, New Century Forum (NCF), The Federation of Textiles Prod. Hong Kong and Kowloon Labour Unions, Civic Passion, Hong Kong Professional Teachers' Union, HK First, New Territories Heung Yee Kuk, Federation of Public Housing Estates, Specialized Inst. Concern Group for Tseung Kwan O People's Livelihood, Democratic Alliance, Kowloon East Food Prod. -

Official Record of Proceedings

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 3 November 2010 1399 OFFICIAL RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 3 November 2010 The Council met at Eleven o'clock MEMBERS PRESENT: THE PRESIDENT THE HONOURABLE JASPER TSANG YOK-SING, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ALBERT HO CHUN-YAN IR DR THE HONOURABLE RAYMOND HO CHUNG-TAI, S.B.S., S.B.ST.J., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEE CHEUK-YAN DR THE HONOURABLE DAVID LI KWOK-PO, G.B.M., G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE FRED LI WAH-MING, S.B.S., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE MARGARET NG THE HONOURABLE JAMES TO KUN-SUN THE HONOURABLE CHEUNG MAN-KWONG THE HONOURABLE CHAN KAM-LAM, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MRS SOPHIE LEUNG LAU YAU-FUN, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEUNG YIU-CHUNG DR THE HONOURABLE PHILIP WONG YU-HONG, G.B.S. 1400 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 3 November 2010 THE HONOURABLE WONG YUNG-KAN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LAU KONG-WAH, J.P. THE HONOURABLE LAU WONG-FAT, G.B.M., G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MIRIAM LAU KIN-YEE, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE EMILY LAU WAI-HING, J.P. THE HONOURABLE ANDREW CHENG KAR-FOO THE HONOURABLE TIMOTHY FOK TSUN-TING, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE TAM YIU-CHUNG, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ABRAHAM SHEK LAI-HIM, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LI FUNG-YING, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE TOMMY CHEUNG YU-YAN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE FREDERICK FUNG KIN-KEE, S.B.S., J.P. -

The RTHK Coverage of the 2004 Legislative Council Election Compared with the Commercial Broadcaster

Mainstream or Alternative? The RTHK Coverage of the 2004 Legislative Council Election Compared with the Commercial Broadcaster so Ming Hang A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Philosophy in Government and Public Administration © The Chinese University of Hong Kong June 2005 The Chinese University of Hong Kong holds the copyright of this thesis. Any person(s) intending to use a part or whole of the materials in the thesis in a proposed publication must seek copyright release from the Dean of the Graduate School. 卜二,A館書圆^^ m 18 1 KK j|| Abstract Theoretically, public broadcaster and commercial broadcaster are set up and run by two different mechanisms. Commercial broadcaster, as a proprietary organization, is believed to emphasize on maximizing the profit while the public broadcaster, without commercial considerations, is usually expected to achieve some objectives or goals instead of making profits. Therefore, the contribution by public broadcaster to the society is usually expected to be different from those by commercial broadcaster. However, the public broadcasters are in crisis around the world because of their unclear role in actual practice. Many politicians claim that they cannot find any difference between the public broadcasters and the commercial broadcasters and thus they asserted to cut the budget of public broadcasters or even privatize all public broadcasters. Having this unstable situation of the public broadcasting, the role or performance of the public broadcasters in actual practice has drawn much attention from both policy-makers and scholars. Empirical studies are divergent on whether there is difference between public and commercial broadcaster in actual practice. -

Dissenting Media in Post-1997 Hong Kong Joyce Y.M. Nip the De

Dissenting media in post-1997 Hong Kong Joyce Y.M. Nip The de-colonization of Hong Kong took the form of Britain returning the territory to China in 1997 as a Special Administrative Region (SAR). Twenty years after the political handover, the “one country, two systems” arrangement designed by China to govern the Hong Kong SAR is facing serious challenge: Many in Hong Kong have come to regard Beijing as an unwelcome control master; and calls for self-determination have gained a substantial level of popular support. This chapter examines the role of media in this development, as exemplified by key political protest actions. It proposes the notion of “dissenting media” as a framework to integrate relevant academic and journalistic studies about Hong Kong. From the discipline of media and communications study, it suggests that operators of dissenting media are enabled to put forth information and analysis contrary to that of the establishment, which, in turn, help to form an oppositional public sphere. In the process, the identity and communities of dissent are built, maintained, and developed, contributing to the formation of a counter public that participates in oppositional political actions. Studies on the impact of media, mainly conducted in stable Anglo-American societies, tend to consider mainstream media as institutions that index1 or reinforce the status quo,2 and alternative media as forces that challenge established powers.3 In Hong Kong, the 1997 political changeover was accompanied by a reconfiguration of power relationships in line with China’s one-party dictatorship. The change runs counter to the political aspirations of the people of Hong Kong, and has bred a political movement for civil liberties, public accountability, and democracy. -

Minutes Have Been Seen by the Administration)

立法會 Legislative Council Ref : CB2/PL/HA LC Paper No. CB(2)1229/17-18 (These minutes have been seen by the Administration) Panel on Home Affairs Minutes of meeting held on Monday, 22 January 2018, at 8:30 am in Conference Room 3 of the Legislative Council Complex Members : Hon MA Fung-kwok, SBS, JP (Chairman) present Hon YUNG Hoi-yan (Deputy Chairman) Hon CHAN Hak-kan, BBS, JP Hon Claudia MO Hon Steven HO Chun-yin, BBS Hon YIU Si-wing, BBS Hon CHAN Chi-chuen Hon LEUNG Che-cheung, SBS, MH, JP Hon Christopher CHEUNG Wah-fung, SBS, JP Hon IP Kin-yuen Hon Andrew WAN Siu-kin Hon CHU Hoi-dick Hon Jimmy NG Wing-ka, JP Dr Hon Junius HO Kwan-yiu, JP Hon Holden CHOW Ho-ding Hon SHIU Ka-fai Hon SHIU Ka-chun Hon Tanya CHAN Hon HUI Chi-fung Hon LUK Chung-hung Hon KWONG Chun-yu Members : Hon Michael TIEN Puk-sun, BBS, JP attending Hon Frankie YICK Chi-ming, SBS, JP Members : Dr Hon Fernando CHEUNG Chiu-hung absent Hon LAU Kwok-fan, MH Hon Kenneth LAU Ip-keung, BBS, MH, JP - 2 - Public Officers : Item III attending Dr LAW Chi-kwong, GBS, JP Chairperson of the Community Care Fund Task Force under the Commission on Poverty Secretary for Labour and Welfare Mr Patrick LI, JP Deputy Secretary for Home Affairs (1) Mr Nick AU YEUNG Principal Assistant Secretary for Home Affairs (Community Care Fund) Ms May CHAN, JP Deputy Secretary for Education (6) Mr FUNG Man-chung Assistant Director (Family and Child Welfare) Social Welfare Department Ms Ivis CHUNG Chief Manager (Allied Health) Hospital Authority Item IV Mr LAU Kong-wah, JP Secretary for Home Affairs Mr -

The Diminishing Power and Democracy of Hong Kong: an Analysis of Hong Kong's Umbrella Movement and the Anti-Extradition Law Amendment Bill Movement

Portland State University PDXScholar University Honors Theses University Honors College Summer 2021 The Diminishing Power and Democracy of Hong Kong: An Analysis of Hong Kong's Umbrella Movement and the Anti-Extradition Law Amendment Bill Movement Xiao Lin Kuang Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/honorstheses Part of the Asian Studies Commons, and the Other International and Area Studies Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Kuang, Xiao Lin, "The Diminishing Power and Democracy of Hong Kong: An Analysis of Hong Kong's Umbrella Movement and the Anti-Extradition Law Amendment Bill Movement" (2021). University Honors Theses. Paper 1126. https://doi.org/10.15760/honors.1157 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in University Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. The diminishing power and democracy of Hong Kong: an analysis of Hong Kong’s Umbrella Movement and the Anti-extradition Law Amendment Bill Movement by Xiao Lin Kuang An undergraduate honors thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts In University Honors And International Development Studies And Chinese Thesis Adviser Maureen Hickey Portland State University 2021 The diminishing power and democracy of Hong Kong Kuang 1 Abstract The future of Hong Kong – one of the most valuable economic port cities in the world – has been a key political issue since the Opium Wars (1839—1860). -

Civic Party (Cp)

立法會 CB(2)1335/17-18(04)號文件 LC Paper No. CB(2)1335/17-18(04) CIVIC PARTY (CP) Submission to the United Nations UNIVERSAL PERIODIC REVIEW Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR) CHINA 31st session of the UPR Working Group of the Human Rights Council November 2018 Introduction 1. We are making a stakeholder’s submission in our capacity as a political party of the pro-democracy camp in Hong Kong for the 2018 Universal Periodic Review on the People's Republic of China (PRC), and in particular, the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR). Currently, our party has five members elected to the Hong Kong Legislative Council, the unicameral legislature of HKSAR. 2. In the Universal Periodic Reviews of PRC in 2009 and 2013, not much attention was paid to the human rights, political, and social developments in the HKSAR, whilst some positive comments were reported on the HKSAR situation. i We wish to highlight that there have been substantial changes to the actual implementation of human rights in Hong Kong since the last reviews, which should be pinpointed for assessment in this Universal Periodic Review. In particular, as a pro-democracy political party with members in public office at the Legislative Council (LegCo), we wish to draw the Council’s attention to issues related to the political structure, election methods and operations, and the exercise of freedom and rights within and outside the Legislative Council in HKSAR. Most notably, recent incidents demonstrate that the PRC and HKSAR authorities have not addressed recommendations made by the Human Rights Committee in previous concluding observations in assessing the implementation of International Convention on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR). -

Reclaiming Their Shadow: Ethnopolitical Mobilization in Consolidated Democracies

Reclaiming their Shadow: Ethnopolitical Mobilization in Consolidated Democracies Ph. D. Dissertation by Britt Cartrite Department of Political Science University of Colorado at Boulder May 1, 2003 Dissertation Committee: Professor William Safran, Chair; Professor James Scarritt; Professor Sven Steinmo; Associate Professor David Leblang; Professor Luis Moreno. Abstract: In recent decades Western Europe has seen a dramatic increase in the political activity of ethnic groups demanding special institutional provisions to preserve their distinct identity. This mobilization represents the relative failure of centuries of assimilationist policies among some of the oldest nation-states and an unexpected outcome for scholars of modernization and nation-building. In its wake, the phenomenon generated a significant scholarship attempting to account for this activity, much of which focused on differences in economic growth as the root cause of ethnic activism. However, some scholars find these models to be based on too short a timeframe for a rich understanding of the phenomenon or too narrowly focused on material interests at the expense of considering institutions, culture, and psychology. In response to this broader debate, this study explores fifteen ethnic groups in three countries (France, Spain, and the United Kingdom) over the last two centuries as well as factoring in changes in Western European thought and institutions more broadly, all in an attempt to build a richer understanding of ethnic mobilization. Furthermore, by including all “national -

Insights for Intra-Party Tensions?

Hong Kong as a proxy battlefield Insights for Intra-Party tensions? Zhang Xiaoming 张晓明, the director of the State Council Hong Kong and Macau Affairs Office 国务 院港澳办, was replaced a few days ago, as vice-director of the small leading group of the same name, by the current Minister of Public Security, Zhao Kezhi 赵克志. That said, it seems Hong Kong’s issues run deeper than just a few personnel appointments. Is the special administrative zone becoming a proxy battleground for opposing political forces inside the Party? The timeline and people involved suggest that parts of the ongoing crisis might have been made by design by outgoing political networks amid the anti-corruption campaign. From the selection of Carrie Lam 林郑月娥, the underpinnings of the Hong Kong and Macau affairs system, to the bid for the London Stock Exchange, there is more than meets the eye. The “Manchurian” Candidate and the Jiangpai From the beginning, the opinion was that Madame Lam would be a short-live replacement for Liang Zhenying 梁振英. Carrie Lam, who actually joined the protest – even for a brief moment – for universal suffrage back in 2014, stayed close to the negotiation with Beijing, unlike some of her counterparts who were refused entry in Shenzhen back in 2015. She then became one of the favorite faces of the administration, especially in late 2016, when Liang Zhenying1 announced he would not be running for re-election. Liang, a representative of the “old regime” – associated with both Zeng Qinghong 曾庆红2 and Zhang Dejiang 张德江, was creating issues leading to the deterioration of the situation in Hong Kong (i.e. -

081216-Keast-YAIA-HK

Hong Kong’s disaffected youths – Is the criticism warranted? December 7, 2016 Jacinta Keast Sixtus ‘Baggio’ Leung and Yau Wai-ching, two young legislators from the localist Youngspiration party, have been barred from Hong Kong’s legislative council (LegCo). Never has China’s National People’s Congress (NPC) jumped to an interpretation on a matter in Hong Kong without a prior request from the local government or courts. This comes after the pair modified their oaths, including enunciating the word ‘China’ as ‘Cheena’ (支那), a derogatory term used by the Japanese in World War II, using expletives to refer to the People’s Republic of China, and waving around blue ‘Hong Kong is not China’ banners at their swearing in. Commentators, including those from the pan-democratic side of the legislature, have called their behaviour infantile, ignorant and thuggish, and have demanded ‘that the hooligans be locked up’. But is this criticism warranted? A growing tide of anti-Mainlander vitriol has been building in Hong Kong since it was handed back to the People’s Republic of China in 1997 under a special constitution termed The Basic Law. In theory, the constitution gave Hong Kong special privileges the Mainland did not enjoy—a policy called ‘One Country, Two Systems’. But in practice, more and more Hong Kong residents feel that the long arm of Beijing’s soft power is extending over the territory. The Occupy movement and later the 2014 Umbrella Revolution began once it was revealed that the Chinese government would be pre-screening candidates for the 2017 Hong Kong Chief Executive election, the election for Hong Kong’s top official. -

Rival Securitising Attempts in the Democratisation of Hong Kong Written by Neville Chi Hang Li

Rival Securitising Attempts in the Democratisation of Hong Kong Written by Neville Chi Hang Li This PDF is auto-generated for reference only. As such, it may contain some conversion errors and/or missing information. For all formal use please refer to the official version on the website, as linked below. Rival Securitising Attempts in the Democratisation of Hong Kong https://www.e-ir.info/2019/03/29/rival-securitising-attempts-in-the-democratisation-of-hong-kong/ NEVILLE CHI HANG LI, MAR 29 2019 This is an excerpt from New Perspectives on China’s Relations with the World: National, Transnational and International. Get your free copy here. The principle of “one country, two systems” is in grave political danger. According to the Joint Declaration on the Question of Hong Kong signed in 1984, and as later specified in Article 5 of the Basic Law, i.e. the mini-constitution of Hong Kong, the capitalist system and way of life in Hong Kong should remain unchanged for 50 years. This promise not only settled the doubts of the Hong Kong people in the 1980s, but also resolved the confidence crisis of the international community due to the differences in the political and economic systems between Hong Kong and the People’s Republic of China (PRC). As stated in the record of a meeting between Thatcher and Deng in 1982, the Prime Minister regarded the question of Hong Kong as an ‘immediate issue’ as ‘money and skill would immediately begin to leave’ if such political differences were not addressed (Margaret Thatcher Foundation 1982).