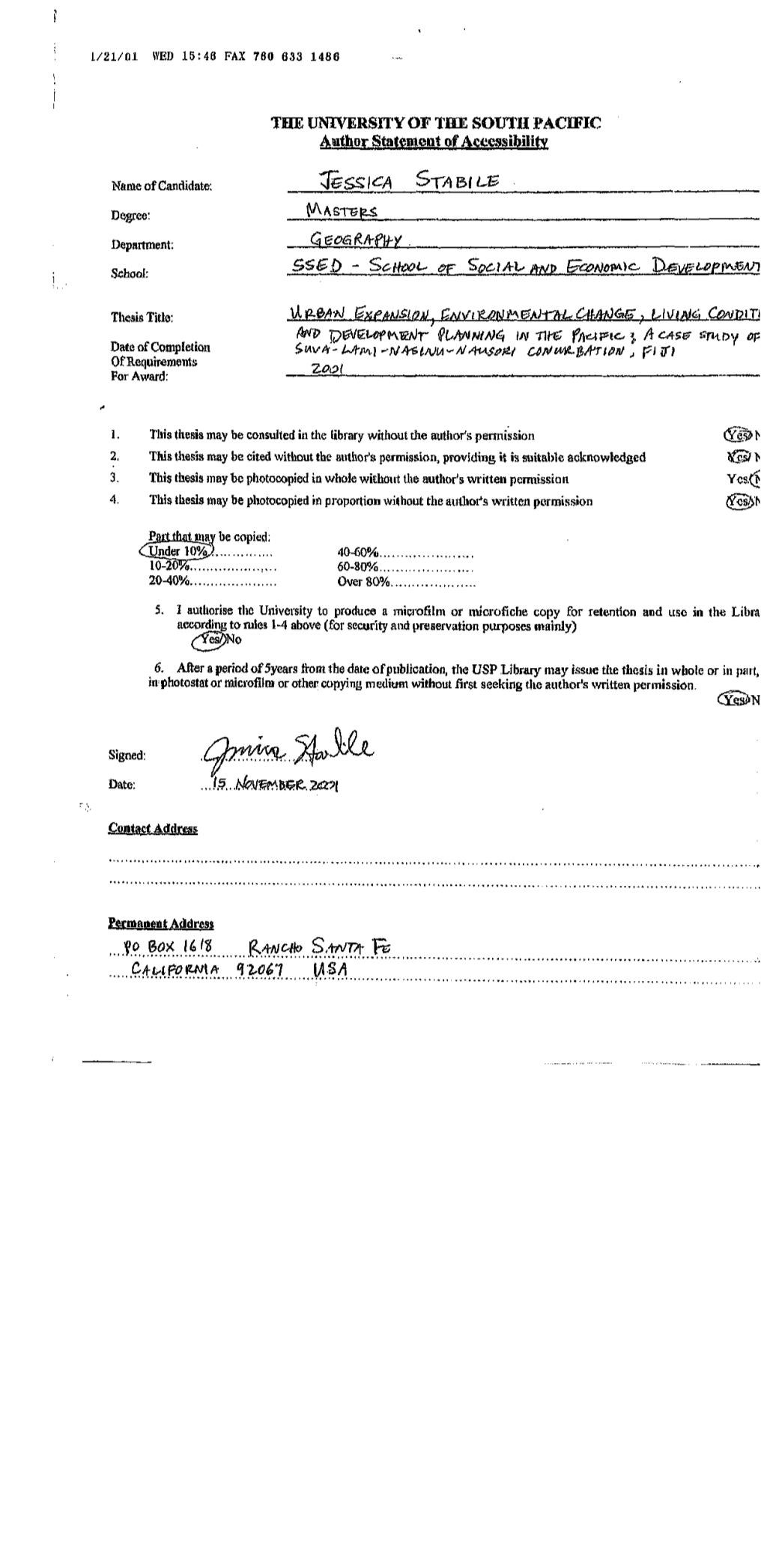

THE UNIVERSITY of the SOUTH PACIFIC Author Statement of Accessibility

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Comparative Study of Land Administration Systems with Special Reference to Armenia, Moldova, Latvia and Kyrgyzstan

LAND ADMINISTRATION REFORM: Indicators of Success, Future Challenges Tony Burns, Chris Grant, Kevin Nettle, Anne-Marie Brits and Kate Dalrymple Version: 13 November 2006 A large body of research recognizes the importance of institutions providing land owners with secure tenure and allowing land to be transferred to more productive uses and users. This implies that, under appropriate circumstances, interventions to improve land administration institutions, in support of these goals, can yield significant benefits. At the same time, to make the case for public investment in land administration, it is necessary to consider both the benefits and the costs of such investments. Given the complexity of the issues involved, designing investments in land administration systems is not straightforward. Systems differ widely, depending on each country’s factor endowments and level of economic development. Investments need to be tailored to suit the prevailing legal and institutional framework and the technical capacity for implementation. This implies that, when designing interventions in this area, it is important to have a clear vision of the long-term goals, to use this to make the appropriate decisions on sequencing, and to ensure that whatever measures are undertaken are cost-effective. This study, which originated in a review of the cost of a sample of World Bank- financed land administration projects over the last decade (carried out by Land Equity International Pty Ltd in collaboration with DECRG), provides useful guidance on a number of fronts. First, by using country cases to draw more general conclusions at a regional level, it illustrates differences in the challenges by region, and on the way these will affect interventions in the area of land administration. -

Twenty Years on Poverty and Hardship in Urban Fiji

Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde Vol. 168, no. 2-3 (2012), pp. 195-218 URL: http://www.kitlv-journals.nl/index.php/btlv URN:NBN:NL:UI:10-1-101733 Copyright: content is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License ISSN: 0006-2294 JENNY BRYANT-TOKALAU Twenty years on Poverty and hardship in urban Fiji Here [in Suva], if we work everyday we can feed ourselves. Five days or 7 days you have to work hard. In farms you don’t have to do much because once you have upgraded all the facilities on your farm it is easy for you. If you earn any amount of money here it will not be sufficient for your family. In Rakiraki [if] you’ve got $50 you earn every week you can provide for your family very well because [of] all the things you can get from the farm. But here if you go to the shop, $200 is nothing for you. Life is better on the farm. (Interview with Hassan 2007.) I was brought up by a single parent – my Mum only. When I was young my grand- parents looked after me in the village (in Rewa). I was educated in the village school from class 1 to class 6. My mum works at domestic duties. I was lucky to come to Suva for my further education. These families helped my Mum with school fees. Since I am not really a clever girl in school I left in Form 5, then I started to have a family at a very young age. -

Fiji Airways COVID-19 Liquidity Support Facility (Fiji)

Report and Recommendation of the President to the Board of Directors Project Number: 54311-001 December 2020 Proposed Loan and Administration of Loan Air Pacific Limited Fiji Airways COVID-19 Liquidity Support Facility (Fiji) This document contains information that is subject to exceptions to disclosure set forth in ADB's Access to Information Policy. Recipients should therefore not disclose its contents to third parties, except in connection with the performance of their official duties. Upon Board approval, ADB will make publicly available an abbreviated version of this document, which will exclude confidential business information and ADB’s assessment of project or transaction risk. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 1 December 2020) Currency unit – Fijian dollar/s (F$) F$1.00 = $0.4827 $1.00 = F$2.0716 ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank COVID-19 – coronavirus disease DFC – United States International Development Finance Corporation EHS – environmental, health, and safety GDP – gross domestic product IATA – International Air Transport Association ICAO – International Civil Aviation Organization LEAP – Leading Asia’s Private Infrastructure Fund NOTES (i) The fiscal year (FY) of the Government of Fiji ends on 31 July. "FY" before a calendar year denotes the year in which the fiscal year ends, e.g., FY2021 ends on 31 July 2021. (ii) In this report, “$” refers to United States dollars, unless otherwise stated. Vice-President Ashok Lavasa, Private Sector Operations and Public–Private Partnerships Director General Michael Barrow, Private Sector Operations Department (PSOD) Deputy Director General Christopher Thieme, PSOD Director Jackie B. Surtani, Infrastructure Finance Division 2 (PSIF2), PSOD Team leader Yeon Su Kim, Investment Specialist, PSIF2, PSOD Team members Genevieve Abel, Principal Transaction Support Specialist (Integrity), Private Sector Transaction Support Division (PSTS), PSOD Augustus Leo S. -

Choice Travel Destination Guide: Fiji Contents

Destination Guide: Fiji What to know before you go Essential preparation and planning tips Accommodation and transport CHOICE TRAVEL DESTINATION GUIDE: FIJI CONTENTS Fiji 2 What you need to know 8 Power plugs 2 Travel-size tips 8 Money 2 Know before you go 9 Travel insurance 2 Best time to go 10 Handy links and apps 3 Culture 3 Language 11 Fiji accommodation and transport 4 Health and safety 11 Flights 5 Laws and watchouts 11 At the airport (and getting to your hotel) 6 Making a complaint 12 Key destinations and their airports 6 Emergency contacts 13 Getting around 14 Driving in Fiji 7 What you need to do 15 Accommodation and tours 7 Visas and passports 7 Vaccinations 7 Phone and internet Who is CHOICE? Set up by consumers for consumers, CHOICE is the consumer advocate that provides Australians with information and advice, free from commercial bias. 1 CHOICE TRAVEL DESTINATION GUIDE: FIJI WHAT YOU NEED TO KNOW OVERVIEW Best time to go, culture, language, health, safety, laws, watchouts, scams, emergency contacts and more. Travel-size tips › You may need vaccinations. Check with your doctor as early as possible before you go. Some › Australians can fly to Fiji in as little as four hours. vaccinations need to be given four to six weeks before departure. › The high season lasts from June to September, and then coincides with the Australian school holiday period in December–January. Best time to go › The dry season runs from May to October. › Visas for Australian passport holders are issued on Dry season: May–October arrival in the country. -

Buresala Training School, Fiji from Journal of Pacific Adventist History

Buresala Training School, Fiji From Journal of Pacific Adventist History. Buresala Training School, Fiji RAYMOND WILKINSON Raymond Wilkinson, Ed.D. (Andrews University, Berrien Springs, Michigan, USA) was born to missionary parents and grew up in Fiji. He was educated at Longburn College, Massey University New Zealand, and Avondale College Australia. With wife Ruth, his Church service involved teaching and educational administration in the South Pacific Islands. He retired 1994 but since then has enjoyed volunteer service in the islands. Now married to Lola, Raymond has four adult children and eight grandchildren. Buresala Training School was the first educational institution designed to train workers that the Seventh-day Adventist (SDA) church operated in Fiji (and, in fact, the South Pacific Islands region). From its opening in February 1905 until the transfer of its programs, in 1940, to what became Fulton College, it prepared a steady stream of ministers, teachers, workers’ spouses, and dedicated church laypeople. In that way, it supported the advancement of the church in Fiji and also in areas of Polynesia and Melanesia, including New Guinea. Early Plans John I. Tay and his wife, Hannah, Americans, were the first Seventh-day Adventist missionaries to Fiji. They arrived by the first voyage of the SDA missionary ship Pitcairn in 1891. Sadly, Tay died on January 8, 1892, after only five months in Fiji.1 In 1894 Americans John Cole and his wife arrived, and they were joined in May 1896 by the American John Fulton and his family.2 John Cole returned to America in 1897 because of ill health, and Fulton was then joined, in 1898, by the American Calvin Parker and his wife.3 Fulton and Parker began visiting Suvavou (New Suva), a village across the harbor from Suva, and one of their first converts was Pauliasi Bunoa, who had been a teacher, an ordained minister, and a missionary to Papua New Guinea for the Wesleyan church. -

Sustainable Urban Mobility in South-Eastern Asia and the Pacific

Sustainable Urban Mobility in South-Eastern Asia and the Pacific Hoong-Chor Chin Regional study prepared for Global Report on Human Settlements 2013 Available from http://www.unhabitat.org/grhs/2013 Hoong-Chor Chin is an Associate Professor and Director of Safety Studies Initiative at the Dept of Civil and Environmental Engineering, National University of Singapore. A Professional Engineer, he has undertaken numerous consultancy and research work on Transportation Planning, Traffic Modelling and Road Safety Studies for local authorities and developers as well as organizations such as Asian Development Bank and Cities Development Initiative for Asia. Comments can be sent to: [email protected]. Disclaimer: This case study is published as submitted by the consultant, and it has not been edited by the United Nations. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries, or regarding its economic system or degree of development. The analysis, conclusions and recommendations of the report do not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations Human Settlements Programme, the Governing Council of the United Nations Human Settlements Programme or its Member States. Nairobi, 2011 Contents 1. The Crisis of Sustainability in Urban Mobility: The Case of South-Eastern -

Issues and Trends

ISSUES AND TRENDS ISSUES AND TRENDS United Nations Human Settlements Programme Nairobi 2012 Gender and Urban Planning: Issues and Trends Copyright © United Nations Human Settlements Programme 2012 All rights reserved United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat) P.O. Box 30030 - 00100 Nairobi GPO Kenya Tel: 254 20 7623120 (Central Kenya) Website: http://www.unhabitat.org Email: habitat.publications.org HS Number: HS/050/12E ISBN Number: 978-92-1-132465-5 Disclaimer The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries, or regarding its economic system or degree of development. The analysis, conclusions and recommendations of this publication do not necessarily reflect the view of the United Nations Human Settlements Programme, the Governing Council of the United Human Settlements Programme, or its Member States. Acknowledgements This report would not have been possible without the contributions and support from many people - academics and practitioners around the world, including members of the Commonwealth Association of Planners (Women in Planning Network), and the Faculty Women’s Interest Group. In addition, we have been able to draw on the extensive work and experience of the UN-Habitat Gender Unit and the Policy Analysis Branch, the Huairou Commission, Oxfam and the Royal Town Planning Institute. Individual thanks go to Alison Brown, Sylvia Chant, Clara Greed, Cliff Hague, Jacqueline Leavitt, Olusola Olufemi, Pragma Patel, Alison Todes, Ed Wensing, Carolyn Whitzman, Leonora Angeles and Alicia Yon. -

Re-Invigorating Private Sector Investment a Private Sector Assessment for Fiji

Re-invigorating Private Sector Investment A Private Sector Assessment for Fiji This private sector assessment reviews Fiji’s private sector environment in 2006–2012, against recommendations made in ADB’s 2005 Promise Unfulfilled: Private Sector Assessment for Fiji. While Fiji has made considerable reform progress in a number of areas (including tax reforms, encouraging telecommunications competition, and reducing barriers to foreign investment), it still faces considerable challenges in responding to a range of macroeconomic shocks following the global economic crisis, and political and policy uncertainty at home. About the Asian Development Bank ADB’s vision is an Asia and Pacific region free of poverty. Its mission is to help its developing member countries reduce poverty and improve the quality of life of their people. Despite the region’s many successes, it remains home to two-thirds of the world’s poor: 1.7 billion people who live on less than $2 a day, with 828 million struggling on less than $1.25 a day. ADB is committed to reducing poverty through inclusive economic growth, environmentally sustainable growth, and regional integration. Based in Manila, ADB is owned by 67 members, including 48 from the region. Its main instruments for helping its developing member countries are policy dialogue, loans, equity investments, guarantees, grants, and technical assistance. Re-invigorating Private Sector Investment A Private Sector Assessment for Asian Development Bank 6 ADB Avenue, Mandaluyong City 1550 Metro Manila, Philippines www.adb.org ISBN 978-92-9254-260-3 Fiji Pacific Liaison and Coordination Office Level 20, 45 Clarence Street Sydney, NSW 2000, Australia www.adb.org/pacific 9 789292 542603 Printed on recycled paper Printed in Australia Re-invigorating Private Sector Investment A Private Sector Assessment for Fiji © 2013 Asian Development Bank All rights reserved. -

Moving to Dangerous Places

12 Moving to dangerous places Eberhard H. Weber, Priya Kissoon, and Camari Koto Mobility is an important part of the discourses around climate change. Many argue that mobility in connection to climate change, natural hazards, or similar is about bringing people to safety, supporting them in their own efforts to reach safe grounds, or as McAdam (2015) puts it: taking people away from “danger zones”. This chapter investigates mobility of people living in informal settlements in Suva, the capital of Fiji, which are exposed to hazards . This chapter, hence concentrates on people moving to highly exposed areas. How can we explain when people move to ‘danger zones’ like is happening in many informal settlements in the Pacific Islands (and surely elsewhere)? Are people not aware that the locations are dangerous, do they not bother to find out, or do they consciously choose such ‘danger zones’? For our study, we undertook interviews and observations in two informal set- tlements in Suva. Our research suggests that the two locations where people estab- lished informal settlements were chosen at least in part because of their unfavour- able environmental conditions. Whether this occurred consciously or more in a reflexive learning process that directed people to locations where they did not face evictions needs to be established in future research. It is becoming evident, howev- er, that in Suva space is becoming scarce. Locations that nobody was interested in several decades ago are now in high demand. This also puts people who live in informal settlements at risk of being evicted by governments’ plans of relocation and/or by market forces, which can be seen as a special form of gentrification. -

Land Transport Perceptions, Procedure, and Planning: a Fiji Urban Case Study

/$1'75$163257 3(5&(37,216352&('85($1'3/$11,1* $),-,85%$1&$6(678'< E\ $QGUHZ*UDQW,UYLQ $WKHVLVVXEPLWWHGLQIXOILOOPHQWRIWKHUHTXLUHPHQWVIRUWKHGHJUHHRI 0DVWHURI6FLHQFHLQ&OLPDWH&KDQJH &RS\ULJKWE\$QGUHZ*UDQW,UYLQ 3DFLILF&HQWUHIRU(QYLURQPHQW 6XVWDLQDEOH'HYHORSPHQW 3D&(6' 7KH8QLYHUVLW\RIWKH6RXWK3DFLILF 1RYHPEHU !&-1#+( .4CcCg<Qox $h@yD"z;$zWh@D?_5zDR5SXRDWWdpipy]5j@S5pTD =D qHe ]hp_D@LD Y ?pk5Yh lp d5DzY5_ t{DWp_ t=_WTEA pz >;W5__qDzb5utWjMWSd5Dz\6_=dYD@KzSD55y@pI5j@DPED :5hWhWWphD?DvRD{D@D6?^hp_D@MDdDhYe5@DWhRDE /WN5zD 7D )5dDh@zD"z5h%~Yh /ADk$*p/` .4FcCm<.wCxZo| 2SDzDD5z?UWhRWVDY8 r}D@h@DzeuDzWWqh5h@se ]jp_DAMD[SDp_D /YO9 zD 6D )6fE,GEy)5_a DXN5Wph 0?WDnWJ?5k@2ET?hY5_BXpy'03 $&.12:/('*(0(17 2YHUWKHSDVWIHZGHFDGHVLQ)LMLWKHUHKDVEHHQDVLJQLILFDQWVKLIWLQDSSURDFK WR QDWLRQDO SULRULWLHV LQ RUGHU WR SURYLGH DFFHVV DQG RSSRUWXQLW\ IRU PRELOLW\ WKURXJKRXWWKHFRXQWU\)LMLVHUYHVDVDGHPRJUDSKLFDOO\GLVWLQFWH[DPSOHDPRQJVW 3DFLILF 6PDOO ,VODQG 'HYHORSLQJ 6WDWHV 36,'6 DV D UHJLRQDO VRFLRSROLWLFDO HFRQRPLFDQGVWUDWHJLFKXE 7R VXSSOHPHQW WKH FRQWULEXWLRQV WRZDUG H[SDQGLQJ WKH XQGHUVWDQGLQJ RI WUDQVSRUWHFRQRP\DQGHQHUJ\UHTXLUHPHQWVLQ6XYD)LML,¶GOLNHWRWKDQN'U3HWHU 1XWWDOO ZKR KDV EHHQ D VXSHUEO\ HQJDJHG VXSHUYLVRU RQ ERWK DQ DFDGHPLF DQG SURIHVVLRQDOOHYHODQG$OLVRQ1HZHOOZKRKDVSURYLGHGLQVWUXPHQWDODGYLFHIURP FRQFHSWLRQWKURXJKFRPSOHWLRQRIWKLVERG\RIUHVHDUFK,KDYHWKHXWPRVWJUDWLWXGH IRUWKHZLOOLQJQHVVRI3URI%RE/OR\GWRVHUYHLQWKHUROHRIP\H[WHUQDODGYLVRU SURYLGLQJQHHGHGJXLGDQFHDWWKHUHOHYDQWMXQFWXUHVLQWKLVSURFHVV,¶GDOVROLNHWR WKDQN3URI0RUJDQ:DLULXZKRKDVSURYLGHGGHSDUWPHQWDOVXSSRUWWKURXJKRXWWKH -

A.HRC.13.22.Add.4.Pdf

UNITED NATIONS A General Assembly Distr. GENERAL A/HRC/13/22/Add.4 26 February 2010 ENGLISH/FRENCH/RUSSIAN/ SPANISH ONLY HUMAN RIGHTS COUNCIL Thirteenth session Agenda item 3 PROMOTION AND PROTECTION OF ALL HUMAN RIGHTS, CIVIL, POLITICAL, ECONOMIC, SOCIAL AND CULTURAL RIGHTS, INCLUDING THE RIGHT TO DEVELOPMENT Report of the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights defenders, Margaret Sekaggya Addendum Responses to the questionnaire on the security ∗ and protection of human rights defenders ∗ The present document is being circulated in the languages of submission only, as it greatly exceeds the word limitations currently imposed by the relevant General Assembly resolutions. GE.10-11602 A/HRC/13/22/Add.4 Page 2 Contents Introduction................................................................................................................................5 I. Questionnaire.........................................................................................................................5 II. Responses received to the questionnaire..............................................................................6 Afghanistan................................................................................................................................6 Albania.......................................................................................................................................8 Algeria .......................................................................................................................................9 -

An Investigation Into Anthroponyms of the Shona Society

AN INVESTIGATION INTO ANTHROPONYMS OF THE SHONA SOCIETY by LIVINGSTONE MAKONDO submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF LITERATURE AND PHILOSOPHY in the subject of AFRICAN LANGUAGES at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA PROMOTER: PROFESSOR D.E. MUTASA JOINT PROMOTER: PROFESSOR D.M. KGOBE JUNE 2009 i DECLARATION Student number 4310-994-2 I, Livingstone Makondo, declare that An investigation anthroponyms of the Shona society is my work and that the sources I have used or quoted have been indicated and acknowledged by means of complete references. ………………………………………….. ………………………………. Signature Date ii ABSTRACT Given names, amongst the Shona people, are an occurrence of language use for specific purposes. This multidisciplinary ethnographic 1890-2006 study explores how insights from pragmatics, semiotics, semantics, among others, can be used to glean the intended and implied meaning(s) of various first names. Six sources namely, twenty seven NADA sources (1931-1977), one hundred and twenty five Shona novels and plays (1957-1998), four newspapers (2005), thirty one graduation booklets (1987-2006), five hundred questionnaires and two hundred and fifty semi-structured interviews were used to gather ten thousand personal names predominantly from seven Shona speaking provinces of Zimbabwe. The study recognizes current dominant given name categories and established eleven broad factors behind the use of given names. It went on to identify twenty-four broad based theme-oriented categories, envisaged naming trends and name categories. Furthermore, popular Shona male and female first names, interesting personal names and those people have reservations with have been recognized. The variety and nature of names Shona people prefer and their favoured address forms were also noted.