The Grape Experiments at Lincoln College

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1.2 Weingartenflächen Und Flächenanteile Der Rebsorten EN

1. Vineyard areas and areas under vine by grape variety Austrian Wine statistics report 1.2 Vineyard areas and areas under vine by grape variety 2 The data in this section is based on the 2015 Survey of Area under Vine, as well as feedback from the wine-producing federal states of Niederösterreich (Lower Austria), Burgenland, Steiermark (Styria) and Wien (Vienna). The main source of data for the 2015 Survey of Area under Vine was the Wein-ONLINE system operated by the Federal Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, Environment and Water Management (BMNT). Data from the remaining federal states was collected by means of a questionnaire (primary data collection). Information relating to the (approved) nurseries was provided by the Burgenland and Lower Austrian Chambers of Agriculture and the Styrian state government (Agricultural Research Centre). According to the 2015 Survey of Area under Vine, Austria’s vineyards occupied 45,574 hectares. The planted vineyard area was 45,439 ha, which corresponds to 94 ha less (or a 0.2% decrease) in comparison to the 2009 Survey of Area under Vine. The long-running trend that suggested a shift away from white wine and towards red was quashed by the 2015 Survey of Area under Vine. While the white wine vineyard area increased by 2.3% to 30,502 ha compared to 2009, the red wine area decreased by 4.9% to 14,937 ha. Figure 1 shows the evolution of Austrian viticulture after the Second World War. The largest area under vine was recorded in 1980 at 59,432 ha. From 1980 onwards, the white wine vineyard area has continuously decreased, while the red wine vineyard area has expanded. -

Creationsfromthebarre Lroom

“… It was our belief that no amount of physical contact could match the healing powers of a well-made cocktail.” – david sedaris —CREATIONS FROM THE BARREL ROOM Our Barrel Room is filled to the brim with not only maturing spirits but fortified wines, house made liqueurs and much more. The following selection is a direct reflection of what’s happening inside those doors. Rhubarb Soda (0%) 14 Rhubarb & vanilla with tonka bean Plum Soda (0%) 14 Plum & Rosemary soda Martini à La Madonna 22 Gin & aromatised verjus stirred with caperberry El Diablo 22 Barrel aged tequila, blackcurrant, ginger & chilli Grapefruit Cobbler 19 pompelmocello, grapefruit, fino sherry with grapefruit bitters Rino Gaetano 22 Rebel yell bourbon, St Felix bitter, Nonino amaro & lemon Amalfi Mist (0%) 12 Bergamot with fresh lemon, champagne vinegar & eucalyptus Clover Club 22 Citadelle reserve gin and mancino ambrato shaken with fresh lemon & raspberries Gimlette 22 Never Never southern strength gin with preserved lime & wild mint cordial Orchard Daiquiri 24 Aged rum, pear, vanilla, cinnamon & chamomile grappa Pineapples 23 Plantation pineapple rum, fresh pineapple juice, Barrel Room port & mace Hanky Panky 25 Widges London dry gin stirred with smoked vermouth & Barrel Room amaro King Sazerac 25 Diplomatico Reserva Exclusiva Rum & coconut oil rye stirred with local honey & absinthe Batida 20 Barrel Room amaro & condensed coconut milk “if you don’t like a taste of the whiskey, it doesn’t mean you don’t like whiskey. It means you haven’t found the right flavour for you.” - dave broom —STRAIGHT FROM THE BARREL La Madonna keeps a small number of barrels for the maturation of cocktails too. -

Domaine Luneau-Papin Muscadet from Domaine Luneau-Papin

Domaine Luneau-Papin Muscadet from Domaine Luneau-Papin. Pierre-Marie Luneau and Marie Chartier. Photo by Christophe Bornet. Pierre and Monique Luneau. Photo by Christophe Bornet. Profile Pierre-Marie Luneau heads this 50-hectare estate in Le Landreau, a village in the heart of Muscadet country, where small hamlets dot a landscape of vineyards on low hills. Their estate, also known as Domaine Pierre de la Grange, has been in existence since the early 18th century when it was already planted with Melon de Bourgogne, the Muscadet appellation's single varietal. After taking over from his father Pierre in 2011, Pierre-Marie became the ninth generation to make wine in the area. Muscadet is an area where, unfortunately, a lot of undistinguished bulk wine is produced. Because of the size of their estate, and of the privileged terroir of the villages of Le Landreau, Vallet and La Chapelle Heulin, the Luneau family has opted for producing smaller cuvées from their several plots, which are always vinified separately so as to reflect their terroir's particular character. The soil is mainly micaschist and gneiss, but some plots are a mix of silica, volcanic rocks and schist. The estate has a high proportion of old vines, 40 years old on average, up to 65 years of age. The harvest is done by hand -also a rarity in the region- to avoid any oxidation before pressing. There is an immediate light débourbage (separation of juice from gross lees), then a 4-week fermentation at 68 degrees, followed by 6 months of aging in stainless-steel vats on fine lees. -

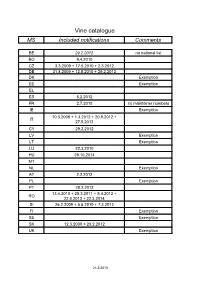

Vine Catalogue MS Included Notifications Comments

Vine catalogue MS Included notifications Comments BE 29.2.2012 no national list BG 9.4.2010 CZ 3.3.2009 + 17.5.2010 + 2.3.2012 DE 31.8.2009 + 12.5.2010 + 29.2.2012 DK Exemption EE Exemption EL ES 8.2.2012 FR 2.7.2010 no maintainer numbers IE Exemption 10.3.2008 + 1.3.2012 + 20.9.2012 + IT 27.5.2013 CY 29.2.2012 LV Exemption LT Exemption LU 22.3.2010 HU 29.10.2014 MT NL Exemption AT 2.2.2012 PL Exemption PT 28.2.2012 13.4.2010 + 25.3.2011 + 5.4.2012 + RO 22.4.2013 + 22.3.2014 SI 26.2.2009 + 5.5.2010 + 7.3.2012 FI Exemption SE Exemption SK 12.3.2009 + 20.2.2012 UK Exemption 21.5.2015 Common catalogue of varieties of vine 1 2 3 4 5 Known synonyms Variety Clone Maintainer Observations in other MS A Abbuoto N. IT 1 B, wine, pas de Abondant B FR matériel certifiable Abouriou B FR B, wine 603, 604 FR B, wine Abrusco N. IT 15 Accent 1 Gm DE 771 N Acolon CZ 1160 N We 725 DE 765 B, table, pas de Admirable de Courtiller B FR matériel certifiable Afuz Ali = Regina Agiorgitiko CY 163 wine, black Aglianico del vulture N. I – VCR 11, I – VCR 14 IT 2 I - Unimi-vitis-AGV VV401, I - Unimi-vitis- IT 33 AGV VV404 I – VCR 7, I – VCR 2, I – Glianica, Glianico, Aglianico N. VCR 13, I – VCR 23, I – IT 2 wine VCR 111, I – VCR 106, I Ellanico, Ellenico – VCR 109, I – VCR 103 I - AV 02, I - AV 05, I - AV 09, I - BN 2.09.014, IT 31 wine I - BN 2.09.025 I - Unimi-vitis-AGT VV411, I - Unimi-vitis- IT 33 wine AGTB VV421 I - Ampelos TEA 22, I - IT 60 wine Ampelos TEA 23 I - CRSA - Regione Puglia D382, I - CRSA - IT 66 wine Regione Puglia D386 Aglianicone N. -

Glass Half-Bottle Bottle Sparkling Chardonnay, Pinot Noir, Pinot Meunier, Villiera Traditional Brut – Stellenbosch, South Africa NV 13

wine glass half-bottle bottle sparkling Chardonnay, Pinot Noir, Pinot Meunier, Villiera Traditional Brut – Stellenbosch, South Africa NV 13 . 52 Chardonnay Lilbert-Fils Cramant Grand Cru Blanc de Blancs – Champagne, France NV . 116 Chardonnay, Pinot Noir, Canard Duchene – Champagne, France NV 20 40 80 Cabernet Franc, Charles Bove Rosé – Touraine, France NV . 58 Chardonnay, Pinot Noir, Meunier JM Seleque Solessence Rosé – Champagne, France NV . 108 Pinot Noir, Barnaut Grand Cru Blanc de Noirs Brut – Champagne, France NV . 95 rosé Grenache, Cinsault, Syrah, Rolle, Chateau des Annibals, Cotes de Provence, France 2020 14 28 5 6 white Pinot Grigio, Tosa – Delle Venezie Monte del Fra, Italy 2018 11 22 44 Falanghina, AIA dei Colombi - Campania, Italy 2019 . 48 Arneis, Sauvignon Blanc, Nada – Piedmont, Italy, 2017 . 60 Albarino, La Marimorena – Casa Rojo, Rias Baixas Spain 2019 12. 24. 4853 Albarino, Abalo Mendez – Rias Baixas, Spain 2018 12 24 48 Sauvignon Blanc, Semillon, Chateau La Garde – Pessac-Leognan, France 2012 . 79 Sauvignon Blanc, Semillon, Delille Cellars “Chaleur Blanc” – Columbia Valley, Washington 2019 14 28 56 Sauvignon Blanc, Ehlers – Napa Valley, California 2016 . 70 Riesling, Mt. Beautiful – North Canterbury, New Zealand 2016 . 49 Verdejo, El Gordo del Circo – Rueda, Spain 2018 . 49 Roussanne, Vermentino, Ollier-Taillefer Allegro Blanc – Languedoc-Roussillon, France 2017 . 64 Chenin Blanc, Domaine Richou – ‘Anjou’ Loire, France 2017 . 56 Pinot Blanc, Kelley Fox Wines – Willamette Valley, Oregon 2018 . 59 Malagousia, Gerovassiliou – Macedonia, Greece 2016 . 59 Chardonnay, David Finlayson – Stellenbosch, South Africa 2019 12 24 48 Chardonnay, Hanzell “Sebella” – Sonoma County, California 2018 . 65 Chardonnay, Poseidon – Carneros, Napa Valley, California 2017 14 28 56 Chardonnay, Dumol ‘Wester Reach’ – Russian River, California 2017 . -

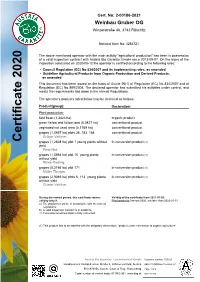

C Ertificate 2020 Weinbau Gruber OG

Cert. No: 2-00186-2021 Weinbau Gruber OG Winzerstraße 46, 3743 Röschitz National farm No: 4284721 The above mentioned operator with the main activity "agricultural production" has been in possession of a valid inspection contract with Austria Bio Garantie GmbH since 2013-09-07. On the basis of the inspection conducted on 2020-08-12 the operator is certified according to the following rules: • Council Regulation (EC) No 834/2007 and its implementing rules, as amended • Guideline Agricultural Products from Organic Production and Derived Products, as amended This document has been issued on the basis of Article 29(1) of Regulation (EC) No 834/2007 and of Regulation (EC) No 889/2008. The declared operator has submitted his activities under control, and meets the requirements laid down in the named Regulations. The operator's products listed below may be declared as follows: Product(group): Declaration: Plant production: field bean (1,3423 ha) organic product green fallow and fallow land (5,0827 ha) conventional product vegetated not used area (0,1769 ha) conventional product grapes (1,0667 ha) plots 36, 183, 184 conventional product Grüner Veltliner Certificate 2020 Certificate grapes (1,2828 ha) plot 1 young plants without in-conversion product (1) yield Pinot Noir grapes (1,0864 ha) plot 10 young plants in-conversion product (1) without yield Rhine Riesling grapes (0,2165 ha) plot 171 in-conversion product (1) Müller Thurgau grapes (2,9046 ha) plots 6, 113 young plants in-conversion product (1) without yield Grüner Veltliner During the named period, this certificate retains Validity of the certificate from 2021-01-08: validity only if: Plant products: harvest 2020, not later than 2022-01-31 a) The products must be in accordance with the named regulations. -

2021 Oregon Harvest Internship Sokol Blosser Winery Dundee, OR

2021 Oregon Harvest Internship Sokol Blosser Winery Dundee, OR Job Description: Sokol Blosser Winery, located in the heart of Oregon's wine country, is one of the state's most well- known wineries. For the upcoming 2021 harvest, we are looking to hire multiple experienced cellar hands, with one individual focused on lab/fermentation monitoring. Our ideal candidates will have 2+ previous harvest experiences, but not required. Amazing forklift skills are a bonus! Our 2021 harvest will focus on the production of both small batch Pinot Noir for our Sokol Blosser brand and large format fermentation for our Evolution brand. Additionally, we work with Pinot Gris, Rose of Pinot Noir, Chardonnay, Sauvignon Blanc, various sparkling bases, Gamay and aromatic varieties such as Riesling, and Müller-Thurgau. Our estate vineyard is certified organic and our company is B-Corp certified. Cellar hand responsibilities • Cleaning and more cleaning • Attention to detail/safety • Harvest tasks including but not limited to (cap management, racking, inoculations, barrel work, cleaning, forklift driving, etc.) • Ability to lift up to 50 lbs., work long hours in variable conditions, follow directions, and accurately fill out work orders • Potential support to lab work including running pH/TA, using equipment such as densitometers/refractometers and data entry We provide • Housing on site • Lunches, and dinners on late nights • Cats and dogs for all your cuteness needs • Football and Frisbee time • End of day quality time with co-workers, work hard-play hard! No phone calls, please. Send your resume and cover letter to [email protected] with the subject line “Harvest 2021”. -

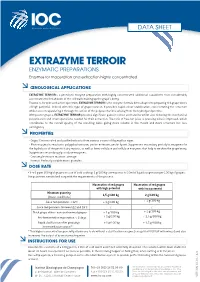

Ft Extrazyme Terroir (En)

DATA SHEET EXTRAZYME TERROIR ENZYMATIC PREPARATIONS Enzymes for maceration and extraction highly concentrated. ŒNOLOGICAL APPLICATIONS EXTRAZYME TERROIRis a pectolytic enzyme preparation with highly concentrated additional capabilities that considerably accelerates the breakdown of the cell walls making up the grape's berry. Thanks to its wide and active spectrum, EXTRAZYME TERROIR is the enzyme formula best adapted to preparing red-grape wines of high potential. Indeed, with this type of grape harvest, it provides rapid colour stabilisation, concentrating the structure whilst also encapsulating it through the action of the polysaccharides arising from the hydrolysed pectins. With poorer grapes, EXTRAZYME TERROIR provides significant gains in colour and tannins whilst also reducing the mechanical pulverisation and other operations needed for their extraction. The ratio of free-run juice to pressing wine is improved, which contributes to the overall quality of the resulting wine, giving more volume in the mouth and more structure but less astringency. PROPERTIES - Origin: Concentrated and purified extracts from various strains of Aspergillus niger. - Main enzymatic reactions: polygalacturonase, pectin esterase, pectin lyase. Suppresses secondary pectolytic enzymes for the hydrolysis of the pectic hairy regions, as well as hemi-cellulase and cellulase enzymes that help to weaken the grape berry. Suppresses secondary glycosidase enzymes. - Cinnamyl esterase reaction: average. - Format: Perfectly soluble micro-granules. DOSE RATE • 3 to 6 -

Wine Flavor 101C: Bottling Line Readiness Oxygen Management in the Bottle

Wine Flavor 101C: Bottling Line Readiness Oxygen Management in the Bottle Annegret Cantu [email protected] Andrew L. Waterhouse Viticulture and Enology Outline Oxygen in Wine and Bottling Challenges . Importance of Oxygen in Wine . Brief Wine Oxidation Chemistry . Physical Chemistry of Oxygen in Wine . Overview Wine Oxygen Measurements . Oxygen Management and Bottling Practices Viticulture and Enology Importance of Oxygen during Wine Production Viticulture and Enology Winemaking and Wine Diversity Louis Pasteur (1822-1895): . Discovered that fermentation is carried out by yeast (1857) . Recommended sterilizing juice, and using pure yeast culture . Described wine oxidation . “C’est l’oxygene qui fait le vin.” Viticulture and Enology Viticulture and Enology Viticulture and Enology Importance of Oxygen in Wine QUALITY WINE OXIDIZED WINE Yeast activity Color stability + Astringency reduction Oxygen Browning Aldehyde production Flavor development Loss of varietal character Time Adapted from ACS Ferreira 2009 Viticulture and Enology Oxygen Control during Bottling Sensory Effect of Bottling Oxygen Dissolved Oxygen at Bottling . Low, 1 mg/L . Med, 3 mg/L . High, 5 mg/L Dimkou et. al, Impact of Dissolved Oxygen at Bottling on Sulfur Dioxide and Sensory Properties of a Riesling Wine, AJEV, 64: 325 (2013) Viticulture and Enology Oxygen Dissolution . Incorporation into juices & wines from atmospheric oxygen (~21 %) by: Diffusion Henry’s Law: The solubility of a gas in a liquid is directly proportional to the partial pressure of the gas above the liquid; C=kPgas Turbulent mixing (crushing, pressing, racking, etc.) Increased pressure More gas molecules Viticulture and Enology Oxygen Saturation . The solution contains a maximum amount of dissolved oxygen at a given temperature and atmospheric pressure • Room temp. -

Official Journal of the European Communities No L 214/ 1

16 . 8 . 80 Official Journal of the European Communities No L 214/ 1 I (Acts whose publication is obligatory) COMMISSION REGULATION (EEC) No 2164/80 of 8 August 1980 amending for the seventh time Regulation ( EEC) No 1608/76 laying down detailed rules for the description and presentation of wines and grape musts THE COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN on an additional label placed in the same field of COMMUNITIES , vision as the other mandatory information ; Having regard to the Treaty establishing the European Economic Community, Whereas the nominal volume of containers with a volume of not less than 5 ml and not more than 10 1 suitable for putting up wines and grape musts which Having regard to Council Regulation (EEC) No are the subject of intra-Community trade is governed 337/79 of 5 February 1979 on the common organi by Council Directive 75/ 106/EEC of 19 December zation of the market in wine ('), as last amended by 1974 on the approximation of the laws of the Regulation (EEC) No 1988 / 80 (2 ), and in particular Member States relating to the making-up by volume Article 54 ( 5) thereof, of certain prepackaged liquids (8 ), as amended by Directive 79/ 1005 /EEC ( 9); whereas it is necessary, Whereas Council Regulation ( EEC) No 355 /79 of first, to adjust Regulation (EEC) No 1608 /76 in line 5 February 1979 laying down general rules for the with the amendments to that Directive and , secondly, description , and presentation of wines and grape in order to enable the wines and grape musts already musts (■'), as amended by Regulation (EEC) No -

Guide H-309: Grape Varieties for North-Central New Mexico

COLLEGE OF AGRICULTURAL, CONSUMER AND ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCES Grape Varieties for North-central New Mexico Revised by William “Gill” Giese and Kevin Lombard1 aces.nmsu.edu/pubs • Cooperative Extension Service • Guide H-309 The College of Agricultural, Consumer and Environmental Sciences is an engine for economic and community development in New © Alika1712 | Dreamstime.com INTRODUCTION Mexico, improving Grapes (Vitis spp.) are the most widely grown perennial fruit crop in the world. They are grown in home gardens for fruit and landscape the lives of New purposes or commercially for wine, raisins, or fresh consumption as “table” grapes. A cultivated variety, or “cultivar,” is a formal term for Mexicans through variety. Variety is the more common term, and will be used in this publication. Selecting grape varieties that are adapted to prevailing academic, research, climatic and soil conditions is an important step before planting. Very few locations above 6,000 feet in elevation are successful grape pro- and Extension duction sites. Suitable growing conditions at lower elevations are still very site-specific due to the major threat to grape culture: winter or programs. frost injury. Winter injury occurs at subfreezing temperatures during vine dormancy when no green tissue is present. Frost injury occurs at subfreezing temperatures when green tissue is present. A variety’s win- ter hardiness, or ability to withstand cold temperatures, depends on its genetic makeup or “type.” In addition to winter hardiness, other considerations when selecting a variety are its fruit characteristics, number of frost-free days required for ripening, disease susceptibility, yield potential, growth habit, and other cultural requirements. -

English All List

Wine Sparkling Residual Award Category Producer Wine Vintage Country Region % Variety 1 % Variety 2 Inporter or Distributor No. Sugar Cabernet 13328 DG Still Red BODEGA NORTON CABERNET SAUVIGNON RESERVA 2014 ARGENTINA MENDOZA 100 ENOTECA CO., LTD. Sauvignon Cabernet 13326 DG Still Red BODEGA NORTON GERNOT LANGES 2012 ARGENTINA MENDOZA 60 Malbec 20 ENOTECA CO., LTD. Sauvignon Cabernet VINOS YAMAZAKI CO., 13003 DG Still Red BODEGAS FABRE S.A. VINALBA RESERVA CABERNET SAUVIGNON 2015 ARGENTINA MENDOZA 100 Sauvignon LTD 13517 DG Still Red MENDOZA VINEYARDS R AND B MALBEC 2013 ARGENTINA MENDOZA 100 Malbec CENTURY TRADING CO., 13524 DG Still Red MYTHIC ESTATE MYTHIC BLOCK MALBEC 2013 ARGENTINA MENDOZA 100 Malbec LTD. 10917 DG Still White PAMPAS DEL SUR EXPRESION ARGENTINA TORRONTES 2016 ARGENTINA MENDOZA 100 Torrontes FOODEM CO., LTD. 12885 DG Still Red VINITERRA SINGLE VINEYARD 2013 ARGENTINA MENDOZA 100 Malbec TOA SHOJI CO., LTD 12270 DG Still Red BODEGA EL ESTECO DON DAVID TANNAT RESERVE 2014 ARGENTINA SALTA 100 Tannat SMILE CORP. 14059 DG Still White CHAKANA MAIPE TORRONTES 2016 ARGENTINA SALTA 100 Torrontes OVERSEAS CO., LTD. Cabernet TOKO TRADING CO., 12728 DG Still Red ELEMENTOS ELEMENTOS CABERNET SAUVIGNON 2016 ARGENTINA SALTA 100 Sauvignon LTD 10532 DG Still White BODEGAS CALLIA ALTA CHARDONNAY - TORRONTES 2016 ARGENTINA SAN JUAN 60 Chardonnay 40 Torrontes MOTTOX INC. SOUTH VINOS YAMAZAKI CO., 11578 DG Still Red 3 RINGS 3 RINGS SHIRAZ 2014 AUSTRALIA 100 Shiraz AUSTRALIA LTD Cabernet ASAHI BREWERIES, 11363 DG Still Red KATNOOK ESTATE KATNOOK ESTATE CABERNET SAUVIGNON 2012 AUSTRALIA SOUTH AUSTRALIA 100 Sauvignon LTD. ASAHI BREWERIES, 11365 DG Still White KATNOOK ESTATE KATNOOK ESTATE CHARDONNAY 2013 AUSTRALIA SOUTH AUSTRALIA 100 Chardonnay LTD.