Chinese and Russian Language Equivalents of the IAU Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature: an Overview of Planetary Toponym Localization Methods

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cassini RADAR Images at Hotei Arcus and Western Xanadu, Titan: Evidence for Geologically Recent Cryovolcanic Activity S

GEOPHYSICAL RESEARCH LETTERS, VOL. 36, L04203, doi:10.1029/2008GL036415, 2009 Click Here for Full Article Cassini RADAR images at Hotei Arcus and western Xanadu, Titan: Evidence for geologically recent cryovolcanic activity S. D. Wall,1 R. M. Lopes,1 E. R. Stofan,2 C. A. Wood,3 J. L. Radebaugh,4 S. M. Ho¨rst,5 B. W. Stiles,1 R. M. Nelson,1 L. W. Kamp,1 M. A. Janssen,1 R. D. Lorenz,6 J. I. Lunine,5 T. G. Farr,1 G. Mitri,1 P. Paillou,7 F. Paganelli,2 and K. L. Mitchell1 Received 21 October 2008; revised 5 January 2009; accepted 8 January 2009; published 24 February 2009. [1] Images obtained by the Cassini Titan Radar Mapper retention age comparable with Earth or Venus (500 Myr) (RADAR) reveal lobate, flowlike features in the Hotei [Lorenz et al., 2007]). Arcus region that embay and cover surrounding terrains and [4] Most putative cryovolcanic features are located at mid channels. We conclude that they are cryovolcanic lava flows to high northern latitudes [Elachi et al., 2005; Lopes et al., younger than surrounding terrain, although we cannot reject 2007]. They are characterized by lobate boundaries and the sedimentary alternative. Their appearance is grossly relatively uniform radar properties, with flow features similar to another region in western Xanadu and unlike most brighter than their surroundings. Cryovolcanic flows are of the other volcanic regions on Titan. Both regions quite limited in area compared to the more extensive dune correspond to those identified by Cassini’s Visual and fields [Radebaugh et al., 2008] or lakes [Hayes et al., Infrared Mapping Spectrometer (VIMS) as having variable 2008]. -

10Great Features for Moon Watchers

Sinus Aestuum is a lava pond hemming the Imbrium debris. Mare Orientale is another of the Moon’s large impact basins, Beginning observing On its eastern edge, dark volcanic material erupted explosively and possibly the youngest. Lunar scientists think it formed 170 along a rille. Although this region at first appears featureless, million years after Mare Imbrium. And although “Mare Orien- observe it at several different lunar phases and you’ll see the tale” translates to “Eastern Sea,” in 1961, the International dark area grow more apparent as the Sun climbs higher. Astronomical Union changed the way astronomers denote great features for Occupying a region below and a bit left of the Moon’s dead lunar directions. The result is that Mare Orientale now sits on center, Mare Nubium lies far from many lunar showpiece sites. the Moon’s western limb. From Earth we never see most of it. Look for it as the dark region above magnificent Tycho Crater. When you observe the Cauchy Domes, you’ll be looking at Yet this small region, where lava plains meet highlands, con- shield volcanoes that erupted from lunar vents. The lava cooled Moon watchers tains a variety of interesting geologic features — impact craters, slowly, so it had a chance to spread and form gentle slopes. 10Our natural satellite offers plenty of targets you can spot through any size telescope. lava-flooded plains, tectonic faulting, and debris from distant In a geologic sense, our Moon is now quiet. The only events by Michael E. Bakich impacts — that are great for telescopic exploring. -

July 2020 in This Issue Online Readers, ALPO Conference November 6-7, 2020 2 Lunar Calendar July 2020 3 Click on Images an Invitation to Join ALPO 3 for Hyperlinks

A publication of the Lunar Section of ALPO Edited by David Teske: [email protected] 2162 Enon Road, Louisville, Mississippi, USA Recent back issues: http://moon.scopesandscapes.com/tlo_back.html July 2020 In This Issue Online readers, ALPO Conference November 6-7, 2020 2 Lunar Calendar July 2020 3 click on images An Invitation to Join ALPO 3 for hyperlinks. Observations Received 4 By the Numbers 7 Submission Through the ALPO Image Achieve 4 When Submitting Observations to the ALPO Lunar Section 9 Call For Observations Focus-On 9 Focus-On Announcement 10 2020 ALPO The Walter H. Haas Observer’s Award 11 Sirsalis T, R. Hays, Jr. 12 Long Crack, R. Hill 13 Musings on Theophilus, H. Eskildsen 14 Almost Full, R. Hill 16 Northern Moon, H. Eskildsen 17 Northwest Moon and Horrebow, H. Eskildsen 18 A Bit of Thebit, R. Hill 19 Euclides D in the Landscape of the Mare Cognitum (and Two Kipukas?), A. Anunziato 20 On the South Shore, R. Hill 22 Focus On: The Lunar 100, Features 11-20, J. Hubbell 23 Recent Topographic Studies 43 Lunar Geologic Change Detection Program T. Cook 120 Key to Images in this Issue 134 These are the modern Golden Days of lunar studies in a way, with so many new resources available to lu- nar observers. Recently, we have mentioned Robert Garfinkle’s opus Luna Cognita and the new lunar map by the USGS. This month brings us the updated, 7th edition of the Virtual Moon Atlas. These are all wonderful resources for your lunar studies. -

Collimation and User-Friendliness Aspect

Patrick Moore’s Practical Astronomy Series Other Titles in this Series Telescopes and Techniques (2nd Edn.) Light Pollution Chris Kitchin Bob Mizon The Art and Science of CCD Astronomy Using the Meade ETX David Ratledge (Ed.) Mike Weasner The Observer’s Year (Second Edition) Practical Amateur Spectroscopy Patrick Moore Stephen F. Tonkin (Ed.) Seeing Stars More Small Astronomical Observatories Chris Kitchin and Robert W. Forrest Patrick Moore (Ed.) Photo-guide to the Constellations Observer’s Guide to Stellar Evolution Chris Kitchin Mike Inglis The Sun in Eclipse How to Observe the Sun Safely Michael Maunder and Patrick Moore Lee Macdonald Software and Data for Practical Astronomers The Practical Astronomer’s Deep-Sky Companion David Ratledge Jess K. Gilmour Amateur Telescope Making Observing Comets Stephen F. Tonkin (Ed.) Nick James and Gerald North Observing Meteors, Comets, Supernovae and other Observing Variable Stars Transient Phenomena Gerry A. Good Neil Bone Visual Astronomy in the Suburbs Astronomical Equipment for Amateurs Antony Cooke Martin Mobberley Astronomy of the Milky Way: The Observer’s Transit: When Planets Cross the Sun Guide to the Northern and Southern Milky Way Michael Maunder and Patrick Moore (2 volumes) Practical Astrophotography Mike Inglis Jeffrey R. Charles The NexStar User’s Guide Observing the Moon Michael W. Swanson Peter T. Wlasuk Observing Binary and Double Stars Deep-Sky Observing Bob Argyle (Ed.) Steven R. Coe Navigating the Night Sky AstroFAQs Guilherme de Almeida Stephen Tonkin The New Amateur Astronomer The Deep-Sky Observer’s Year Martin Mobberley Grant Privett and Paul Parsons Care of Astronomical Telescopes Field Guide to the Deep Sky Objects and Accessories Mike Inglis M. -

Lunar Club Observations

Guys & Gals, Here, belatedly, is my Christmas present to you. I couldn’t buy each of you a lunar map, so I did the next best thing. Below this letter you’ll find a guide for observing each of the 100 lunar features on the A. L.’s Lunar Club observing list. My guide tells you what the features are, where they are located, what instrument (naked eyes, binoculars or telescope) will give you the best view of them and what you can expect to see when you find them. It may or may not look like it, but this project involved a massive amount of work. In preparing it, I relied heavily on three resources: *The lunar map I used to determine which quadrant of the Moon each feature resides in is the laminated Sky & Telescope Lunar Map – specifically, the one that shows the Moon as we see it naked-eye or in binoculars. (S&T also sells one with the features reversed to match the view in a refracting telescope for the same price.); and *The text consists of information from (a) my own observing notes and (b) material in Ernest Cherrington’s Exploring the Moon Through Binoculars and Small Telescopes. Both the map and Cherrington’s book were door prizes at our Dec. Christmas party. My goal, of course, is to get you interested in learning more about our nearest neighbor in space. The Moon is a fascinating and lovely place, and one that all too often is overlooked by amateur astronomers. But of all the objects in the night sky, the Moon is the most accessible and easiest to observe. -

Estimating Erosional Exhumation on Titan from Drainage Network Morphology

Estimating erosional exhumation on Titan from drainage network morphology The MIT Faculty has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters. Citation Black, Benjamin A., J. Taylor Perron, Devon M. Burr, and Sarah A. Drummond. “Estimating Erosional Exhumation on Titan from Drainage Network Morphology.” Journal of Geophysical Research 117, no. E8 (2012). Copyright © 2012 American Geophysical Union As Published http://dx.doi.org/10.1029/2012je004085 Publisher American Geophysical Union (AGU) Version Final published version Citable link http://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/85624 Terms of Use Article is made available in accordance with the publisher's policy and may be subject to US copyright law. Please refer to the publisher's site for terms of use. JOURNAL OF GEOPHYSICAL RESEARCH, VOL. 117, E08006, doi:10.1029/2012JE004085, 2012 Estimating erosional exhumation on Titan from drainage network morphology Benjamin A. Black,1 J. Taylor Perron,1 Devon M. Burr,2 and Sarah A. Drummond2 Received 20 March 2012; revised 15 June 2012; accepted 26 June 2012; published 15 August 2012. [1] Drainage networks on Titan, Earth, and Mars provide the only known examples of non-volcanic fluvial activity in our solar system. The drainage networks on Titan are apparently the result of a methane-ethane cycle similar to Earth’s water cycle. The scarcity of impact craters and the uneven distribution of fluvial dissection on Titan suggest that the surface may be relatively young. The purpose of this study is to assess the importance of erosion relative to other plausible mechanisms of resurfacing such as tectonic deformation, cryovolcanism, or deposition of aerosols. -

Thumbnail Index

Thumbnail Index The following five pages depict each plate in the book and provide the following information about it: • Longitude and latitude of the main feature shown. • Sun’s angle (SE), ranging from 1°, with grazing illumination and long shadows, up to 72° for nearly full Moon conditions with the Sun almost overhead. • The elevation or height (H) in kilometers of the spacecraft above the surface when the image was acquired, from 21 to 116 km. • The time of acquisition in this sequence: year, month, day, hour, and minute in Universal Time. 1. Gauss 2. Cleomedes 3. Yerkes 4. Proclus 5. Mare Marginis 79°E, 36°N SE=30° H=65km 2009.05.29. 05:15 56°E, 24°N SE=28° H=100km 2008.12.03. 09:02 52°E, 15°N SE=34° H=72km 2009.05.31. 06:07 48°E, 17°N SE=59° H=45km 2009.05.04. 06:40 87°E, 14°N SE=7° H=60km 2009.01.10. 22:29 6. Mare Smythii 7. Taruntius 8. Mare Fecunditatis 9. Langrenus 10. Petavius 86°E, 3°S SE=19° H=58km 2009.01.11. 00:28 47°E, 6°N SE=33° H=72km 2009.05.31. 15:27 50°E, 7°S SE=10° H=64km 2009.01.13. 19:40 60°E, 11°S SE=24° H=95km 2008.06.08. 08:10 61°E, 23°S SE=9° H=65km 2009.01.12. 22:42 11.Humboldt 12. Furnerius 13. Stevinus 14. Rheita Valley 15. Kaguya impact point 80°E, 27°S SE=42° H=105km 2008.05.10. -

Life and Death in the Shadow of Vesuvius

Life and death in the shadow of Vesuvius The following Educator’s Guide for A Day in Pompeii was designed to promote personalized learning and reinforce classroom curriculum. The worksheets and classroom activities are appropriate for various grade levels and apply to proficiency standards in social studies, language arts, reading, math, science and the arts. Students are encouraged to use their investigation skills to describe, explain, analyze, summarize, record and evaluate the information presented in the exhibit. The information gathered can then be used as background research for the various Classroom Connections that relate to grade level academic content standards. In order to best suit you and your classroom needs, this Educator’s Guide has been broken up into the following areas: A. Pre-visit Information Background Information i. Vocabulary ii. Volcanism 1. Types of Volcanoes 2. Advantages of Volcanoes iii. Mt. Vesuvius iv. Pompeii Classroom Connections B. Museum Visit Information Exhibit Walk-through Exhibit Student Worksheet C. Post-visit Information Classroom Connections i. Language Arts/Social Studies ii. Science iii. Fine Arts Further Readings Ohio and National Standards PRE-VISIT INFORMATION Vocabulary Archaeologist – A scientist who studies artifacts of the near and distant past in order to develop a picture of how people lived in earlier cultures and societies. These artifacts include physical remains, such as graves, tools and pottery. Artifact – A hand-made object or the remains of an object that is characteristic of an earlier time or culture, such as an object found at an archaeological excavation. Caldera – A cauldron-like depression in the ground created by the collapse of land after a volcanic eruption. -

Prerequisites for Explosive Cryovolcanism on Dwarf Planet-Class Kuiper Belt Objects ⇑ M

Icarus 246 (2015) 48–64 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Icarus journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/icarus Prerequisites for explosive cryovolcanism on dwarf planet-class Kuiper belt objects ⇑ M. Neveu a, , S.J. Desch a, E.L. Shock a,b, C.R. Glein c a School of Earth and Space Exploration, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ 85287-1404, USA b Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ 85287-1404, USA c Geophysical Laboratory, Carnegie Institution of Washington, 5251 Broad Branch Rd. NW, Washington, DC 20015, USA article info abstract Article history: Explosive extrusion of cold material from the interior of icy bodies, or cryovolcanism, has been observed Received 30 December 2013 on Enceladus and, perhaps, Europa, Triton, and Ceres. It may explain the observed evidence for a young Revised 21 March 2014 surface on Charon (Pluto’s surface is masked by frosts). Here, we evaluate prerequisites for cryovolcanism Accepted 25 March 2014 on dwarf planet-class Kuiper belt objects (KBOs). We first review the likely spatial and temporal extent of Available online 5 April 2014 subsurface liquid, proposed mechanisms to overcome the negative buoyancy of liquid water in ice, and the volatile inventory of KBOs. We then present a new geochemical equilibrium model for volatile exso- Keywords: lution and its ability to drive upward crack propagation. This novel approach bridges geophysics and geo- Charon chemistry, and extends geochemical modeling to the seldom-explored realm of liquid water at subzero Interiors Pluto temperatures. We show that carbon monoxide (CO) is a key volatile for gas-driven fluid ascent; whereas Satellites, formation CO2 and sulfur gases only play a minor role. -

Structural and Tidal Models of Titan and Inferences on Cryovolcanism

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Institute of Transport Research:Publications JournalofGeophysicalResearch: Planets RESEARCH ARTICLE Structural and tidal models of Titan and inferences 10.1002/2013JE004512 on cryovolcanism Key Points: F. Sohl1, A. Solomonidou2,3,4, F. W. Wagner1,5, A. Coustenis2, H. Hussmann1, and D. Schulze-Makuch6,7 • Interior models and amplitude patterns of diurnal tidal stresses 1DLR, Institute of Planetary Research, Berlin, Germany, 2LESIA, Observatoire de Paris, CNRS, UPMC University Paris 06, are calculated University Paris-Diderot-Meudon, Paris, France, 3Department of Geology and Geoenvironment, National and Kapodistrian • The diurnal tidal stress pattern 4 is compliant with cryovolcanic University of Athens, Athens, Greece, Now at Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, 5 6 candidate areas California, USA, Westphalian Wilhelms-University, Institute for Planetology, Münster, Germany, School of Earth and • A warm, low-ammonia ocean could Environmental Sciences, Washington State University, Pullman, Washington, USA, 7Center for Astronomy and increase Titan’s habitable potential Astrophysics, Technical University of Berlin, Berlin, Germany Correspondence to: F. Sohl, Abstract Titan, Saturn’s largest satellite, is subject to solid body tides exerted by Saturn on the timescale [email protected] of its orbital period. The tide-induced internal redistribution of mass results in tidal stress variations, which could play a major role for Titan’s geologic surface record. We construct models of Titan’s interior that are Citation: consistent with the satellite’s mean density, polar moment-of-inertia factor, obliquity, and tidal potential Sohl, F., A. Solomonidou, F. W. -

Guide to Observing the Moon

Your guide to The Moonby Robert Burnham A supplement to 618128 Astronomy magazine 4 days after New Moon south is up to match the view in a the crescent moon telescope, and east lies to the left. f you look into the western sky a few evenings after New Moon, you’ll spot a bright crescent I glowing in the twilight. The Moon is nearly everyone’s first sight with a telescope, and there’s no better time to start watching it than early in the lunar cycle, which begins every month when the Moon passes between the Sun and Earth. Langrenus Each evening thereafter, as the Moon makes its orbit around Earth, the part of it that’s lit by the Sun grows larger. If you look closely at the crescent Mare Fecunditatis zona I Moon, you can see the unlit part of it glows with a r a ghostly, soft radiance. This is “the old Moon in the L/U. p New Moon’s arms,” and the light comes from sun- /L tlas Messier Messier A a light reflecting off the land, clouds, and oceans of unar Earth. Just as we experience moonlight, the Moon l experiences earthlight. (Earthlight is much brighter, however.) At this point in the lunar cycle, the illuminated Consolidated portion of the Moon is fairly small. Nonetheless, “COMET TAILS” EXTENDING from Messier and Messier A resulted from a two lunar “seas” are visible: Mare Crisium and nearly horizontal impact by a meteorite traveling westward. The big crater Mare Fecunditatis. Both are flat expanses of dark Langrenus (82 miles across) is rich in telescopic features to explore at medium lava whose appearance led early telescopic observ- and high magnification: wall terraces, central peaks, and rays. -

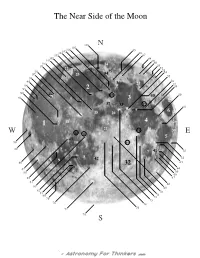

A Map of the Visible Side of the Moon

The Near Side of the Moon 108 N 107 106 105 45 104 46 103 47 102 48 101 49 100 24 50 99 51 52 22 53 98 33 35 54 97 34 23 55 96 95 56 36 25 57 94 58 93 2 92 44 15 40 59 91 3 27 37 17 38 60 39 6 19 20 26 28 1 18 4 29 21 11 30 W 12 E 14 5 43 90 10 16 89 7 41 61 8 62 9 42 88 32 63 87 64 86 31 65 66 85 67 84 68 83 69 82 81 70 80 71 79 72 73 78 74 77 75 76 S Maria (Seas) Craters 1 - Oceanus Procellarum (Ocean of Storms) 45 - Aristotles 77 - Tycho 2 - Mare Imbrium (Sea of Showers) 46 - Cassini 78 - Pitatus 3 - Mare Serenitatis (Sea of Serenity) 47 - Eudoxus 79 - Schickard 4 - Mare Tranquillitatis (Sea of Tranquility) 48 - Endymion 80 - Mercator 5 - Mare Fecunditatis (Sea of Fertility) 49 - Hercules 81 - Campanus 6 - Mare Crisium (Sea of Crises) 50 - Atlas 82 - Bulliadus 7 - Mare Nectaris (Sea of Nectar) 51 - Mercurius 83 - Fra Mauro 8 - Mare Nubium (Sea of Clouds) 52 - Posidonius 84 - Gassendi 9 - Mare Humorum (Sea of Moisture) 53 - Zeno 85 - Euclides 10 - Mare Cognitum (Known Sea) 54 - Menelaus 86 - Byrgius 18 - Mare Insularum (Sea of Islands) 55 - Le Monnier 87 - Billy 19 - Sinus Aestuum (Bay of Seething) 56 - Vitruvius 88 - Cruger 20 - Mare Vaporum (Sea of Vapors) 57 - Cleomedes 89 - Grimaldi 21 - Sinus Medii (Bay of the Center) 58 - Plinius 90 - Riccioli 22 - Sinus Roris (Bay of Dew) 59 - Magelhaens 91 - Galilaei 23 - Sinus Iridum (Bay of Rainbows) 60 - Taruntius 92 - Encke T 24 - Mare Frigoris (Sea of Cold) 61 - Langrenus 93 - Eddington 25 - Lacus Somniorum (Lake of Dreams) 62 - Gutenberg 94 - Seleucus 26 - Palus Somni (Marsh of Sleep)